When Simon Gray’s Cell Mates had its stage debut, 22 years ago, it became almost instantly famous not for either of its characters – the spy George Blake and his accomplice Sean Bourke – but for its cast. Stephen Fry and Rik Mayall seemed like a golden lineup until Fry walked out after three performances and bad reviews. His departure, which he later ascribed to his bipolar disorder, capsized the show. It’s with these memories of bygone notoriety in mind that Hampstead theatre is presenting a new production, directed by Edward Hall. “Times have changed,” Hall says, “and to some extent we’ve gone back to an atmosphere we recognise more from the cold war years than the 90s. Our relationship with Russia now amplifies more of the ideological and political context of the story. That’s one of the reasons I found it so interesting.”

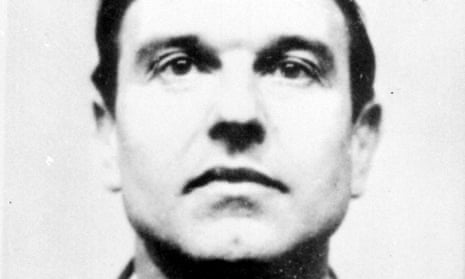

After he was convicted in 1961 of traitorous conduct, Blake stated, “I must freely admit there was not an official document of any importance to which I had access which was not passed to my Soviet contact.” Roger Hermiston’s white-knuckle biography of Blake, The Greatest Traitor, points out the great impact he had on the mythology of spying. (It is so exciting you wish it lingered longer on exactly what subjects he studied as a 13-year-old in Cairo and what possessions he took with him when escaping the Nazi bombardment of Rotterdam.) He inspired John Huston’s film The Mackintosh Man (1973), an unmade Alfred Hitchcock project called The Short Night and a novel by Ted Allbeury; he also makes a cameo appearance in Ian McEwan’s The Innocent.

That parallel, between the cold war and the current atmosphere of suspicion between Russia and the west, helps to explain why we have so easily slipped back into the mutual paranoia of espionage. Yet reading analyses of Blake’s crime, you are reminded less of Putin and his troll factories, more of the way we talk about terrorism, that precise but formless fear of being hated to your very essence. As Harold Macmillan recorded in his diaries:

“Blake asserted he had yielded to no material pressure or advantages but had been genuinely converted to communism while a prisoner of war in Korea. With an ideological spy, we were faced with a phenomenon such as had hardly appeared in these islands for some four hundred years.”

Hermiston traces Blake’s conversion to communism and recounts how he joined the Dutch resistance, in which communists were among the first to organise themselves under Nazi occupation. George Carey, who made the Blake documentary Masterspy of Moscow, has his doubts: “I do think there’s a question mark over whether he changed sides, as he said, genuinely out of conviction, or whether it happened when he was captured by the North Koreans.” In his controversial 1990 autobiography, No Other Choice, Blake is quite clear about his communist beliefs. But the problem with being a spy is that nobody believes you. Because he was thought to represent a severe threat to the nation Blake was sentenced to 42 years in prison.

When he escaped from Wormwood Scrubs in 1966, he did so not only with the help of Bourke – “who went back to Ireland in 1972,” Hall says, “and was given £100,000 to write that story, which he drank” – but aided by a team of fellow prisoners, some of them turning a blind eye. “There were also quite a lot of people from CND who sprung him,” explains Carey. Some of this was for idiosyncratic reasons but mostly because his sentence was considered inhumane. (My father, a psychological assistant at Wormwood Scrubs at the time, wasn’t given to liberal breast-beating about the length of prisoners’ sentences, but he thought Blake’s term was silly, disproportionately long).

In these days of the indeterminate sentence, which could mean a whole life in jail, we have lost a social handle on what’s a reasonable period of incarceration and what isn’t. In the 1960s, the deprivation of liberty was discussed with far more gravity; Lord Mountbatten wrote his report on prison security as a direct result of Blake’s escape, and out of that the parole service – 50 years old this year – was born. Given the collapse of communism in Russia, and its rise in North Korea which can’t have been what anybody had in mind, it is a quirk of the story that probably the most lasting effect Blake had on society was the creation of parole as we know it.

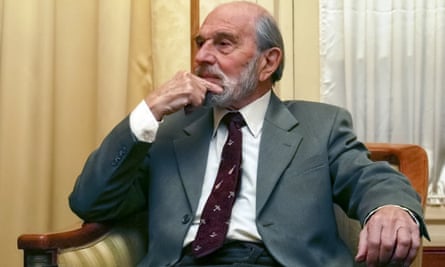

Blake’s story turns to Boy’s Own adventure as he escapes from prison and makes his way to Moscow, but the extraordinary thing is what a success he makes of his life thereafter. He is still alive, and celebrated his 95th birthday last month. “If there’s such a thing as a good traitor, a successful traitor,” Carey says, “he was underrated.”

He never had the glamour of the Cambridge spies, possibly because he wasn’t posh enough, but perhaps because he wasn’t so enmeshed in the society that he turned against. Of Dutch and Egyptian heritage, he was putatively Christian but discovered later in life he was Jewish, with a family history dotted with disinheritance; he didn’t miss Britain when he defected.

“Unlike Guy Burgess, who longed for his clubs, and Kim Philby, who thought he was going to be more significant than he actually was, Blake adapted quite well,” explains Carey. “Burgess and Philby just drank like crazy. Donald Maclean did try to make a life of it, brought his family over. But he too took to drink. They were all very sad guys.” Some wrenches were unavoidable – Blake left a wife and three sons in England and was out of contact until the 1980s. But he went on to have another family in Russia, in a dacha in Kratovo, to the east of Moscow.

Carey doorstepped Blake, including a rare interview with him in his film. I too recently visited Kratovo, which has a reputation for being full of former KGB safe houses, though I couldn’t find one Moscovite who would vouch for that. “If they’d ever been safe houses, we wouldn’t know about it,” came the reply. It resembles a Russian Guildford with high hedges, gigantic trees, the careful, botanical planning of expensive privacy. At the end of Citizen Four, Laura Poitras’s 2014 documentary about Edward Snowden, we see him and his girlfriend through the chalet-like, somehow un-American windows of their new Russian home; the enormity of sacrificing your life to a political act, when politics can change so much, and life can only be lived once, unfurls in one long silent shot.

While Putin’s Russia and the rest of Europe may echo the ancient enmities of the cold war with their highly charged exchanges and their secrecy, their sanctions and their proxy wars, it is not for the sake of communism that these hostilities are nursed. Blake dreamed of the “creation of heaven on Earth”; today’s garden variety nationalism would have bored him. “I don’t think he’s comfortable with Putin at all,” Hall conjectures, “but he can’t say that.”

Carey has a more philosophical take: “He’s disappointed in the way Russians have screwed up communism, but he’s not particularly unhappy there. As he said to me: ‘I’m blind. I can’t really see what it’s like at home. So I may as well be here.’”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion