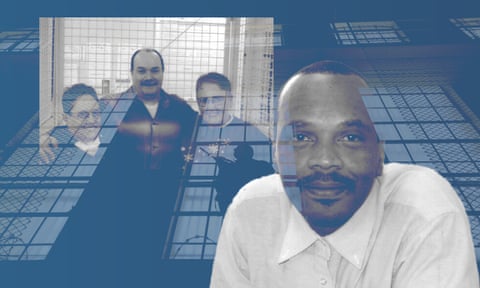

San Quentin prison guards shackled Keith Doolin’s hands behind his back and escorted him to a small cage. It was 8am on a Saturday in early March, and Doolin, along with a dozen other men – all condemned to be executed by the state of California – sat in roughly 6ft by 8ft cells. There were metal bars on all sides and overhead, giving the death row visiting room the appearance of an animal shelter.

Doolin, 50, smiled as he explained why he chose to wear a tattered blue shirt that the prison had given him more than two decades ago. Unlike newer prison uniforms, his outfit has no “inmate” label or “California department of corrections and rehabilitation” (CDCR) marking: “I’ll wear this shirt until it falls off … Here, they strip you of your name and give you a CDC number. It’s part of the psychological warfare – tearing you down, making you feel worthless and not even acknowledging you as a human.”

For 27 years on death row, Doolin has been locked inside a solitary cell, often for 23 hours of the day. In that time, he’s never walked without a guard escort; moved without his hands shackled; used a cellphone or laptop; stepped on grass; or eaten a meal with a group of people.

But Doolin may not be living under these conditions much longer. In March, Governor Gavin Newsom announced that he would be transforming San Quentin, one of the oldest and most notorious prisons in the US, into a “rehabilitation center” modeled after facilities in Norway, which have few restrictions and prioritize comfortable conditions and preparing people to come home. Newsom, who halted executions in 2019, has pledged to close the housing units that make up death row, the largest in the country, to make way for the “pre-eminent restorative justice facility in the world”.

The 546 San Quentin residents on death row will continue to have death sentences, but will be transferred to the general population of prisons across the state – which is likely to give them some basic amenities and small freedoms of movement they’ve been denied for decades.

In dozens of interviews with men living through the final days of San Quentin’s death row facilities, some described a fresh sense of hope, while others spoke of their deep anxieties and fears about the change. Many are left pondering: what does it mean to leave death row if you’re still sentenced to execution? And if the governor is serious about reform, will they ever get to experience life outside of prison?

San Quentin prison, established in 1852, sits on a peninsula north of San Francisco, with picturesque views of the bay and a long, winding bridge that disappears into the fog in the distance. A tall watchtower near the edge of the shore overlooks the walled complex, which has four large cell blocks and a maximum-security facility.

It’s hard to see the water or much of anything outside for those imprisoned in East Block, which houses death row, with five floors of roughly 4ft by 10ft cells stacked on one another – “like sardines in a can”, Doolin said. Each room has a toilet, sink and a steel-frame bed.

“I live 200 feet from the ocean, but I can’t stick my feet in it,” said Doolin. “One day, I’d love to go to a beach, put my toes in the sand, watch the waves and just take a deep breath.” In his cell, small enough to touch both walls at the same time, Doolin sleeps on the floor, so he can use his bed as his desk to store hundreds of legal papers and his most prized possession – his typewriter.

Doolin, a former truck driver, has dealt with the threat of execution by pouring most of his waking hours into his legal efforts to prove his innocence: “Your mind and body and soul are tested here. This place is built for destroying your willpower. But I’m not going to shut up and sit in the corner. I’ll keep fighting with what little I have.”

Doolin, who was convicted of killing two sex workers and shooting four others, signs all his mail “factual innocent man behind bars since 10/18/1995”. His attorneys submitted evidence suggesting a witness for the prosecution was responsible for one of the murders. Following this person’s suicide in 2001 while in jail for another murder, her attorney filed a declaration saying he had information “exonerating” Doolin, but would not disclose it unless a court waived his attorney-client privilege. Doolin has also argued ineffectual counsel after his appointed trial lawyer, who had recently gone bankrupt amid gambling debts, pocketed most of the funds meant for investigators and experts.

In the visiting room, Doolin ate a frozen burger from a vending machine outside of his cage. “It’s amazing how something so simple can mean so much,” he said. Around him, the other men of death row sat with their mothers and partners, eating snacks and microwaved food that visitors can buy for them and playing cards as officers stood by. The staff allowed them to briefly hug inside their cells, though a sign nearby warned against “excessive displays of affection”.

Doolin is anxious about the upcoming transfers. He’s worried he won’t be able to keep his typewriter and doesn’t know how he’ll store all his legal papers if he’s in a shared cell. He’s also scared of being transferred farther from his lawyers in San Francisco and his mother, who lives in Redding, three hours north of San Quentin.

“Being forcibly moved to another prison, it adds another 10,000 pounds of weight on my shoulders. What if I’m moved down south and am twice as far from my family and my lawyers?”

In 2020, CDCR began a pilot program that allowed 100 of those condemned to death to voluntarily transfer off death row and move to other prisons, a process that will now become mandatory for all with death sentences.

Ramon Rogers, 63, and on death row since 1997, jumped at the opportunity: “I was itching to get out of there. I knew there were going to be better and brighter things in store for me than what I had to look forward to in the last 24 years.”

Leaving death row was immediately overwhelming. His group of about a dozen men, heading to a prison outside Los Angeles in July 2021, made a brief stop in the Central Valley, and as they stepped off of their bus, many of them froze in their tracks, he said.

For the first time in decades, they were standing on grass.

When they explained to a guard why they were so stunned, the officer allowed them to walk to an even lusher patch of grass nearby. “We just marveled at the softness and the smell of the grass and the earth. It was remarkable. The officer let us stand there and watch as we left our footprints in the grass. It’s just an amazing thing that people take for granted.”

At their new prison, Correll Thomas, 49, who had been on death row since 1999, experienced sensory overload: “On the yard, it’s just movement – people running laps at different speeds, people doing push-ups and exercising, someone’s throwing a football back and forth, people playing soccer while others are playing football. I was keeping my head on a swivel, trying to take in as much as I can, turning right to left every two seconds. On death row, we don’t have such fast movements.”

Being able to leave his cell without handcuffs and without a full-body strip search was also a welcome change: “For 22 years, I was handcuffed and escorted around like I was an animal. Now I don’t have to strip down naked when I’m called for a medical appointment any more. It’s a lot more freedom.”

Rogers, now in a prison in San Diego, said some men were so conditioned to being shackled that they continued to put their hands in that position even when they were no longer handcuffed. He said he’d also come to appreciate the little things – getting a cold ice-cream from the canteen, or doing yard time in the evening, allowing him to, for the first time in his incarceration, see the night sky.

California’s first execution was a hanging at San Quentin in 1893. Five hundred people were subsequently put to death until the state supreme court struck down the death penalty in 1972, deeming it “impermissibly cruel”. Voters, however, quickly approved a ballot measure to restore capital punishment, and since 1978, more than 1,000 people have been condemned to death, though only 13 have been executed, as appeals take decades. The most recent execution was in 2006 by lethal injection.

There are severe disparities in this system, which has cost the state $4bn since the 1970s. Black people make up 6.5% of California’s population, but more than one-third of those on death row. The vast majority of those sentenced to death over the last decade have been people of color. At least one-third of people on death row also have diagnosed serious mental illnesses, and the population is ageing, with 250 people age 60 and older, 38% of the population. There are 20 women with death sentences, housed in the state’s largest women’s prison.

East Block looks like a parking lot for wheelchairs these days, Doolin said, given how many residents are elderly and disabled.

While there is growing bipartisan opposition to the death penalty, including from some victims’ advocates, the plan to close San Quentin’s death row has been met with skepticism and concern from some of the “condemned” population, with their attorneys and family members raising questions about how the transition will affect their cases.

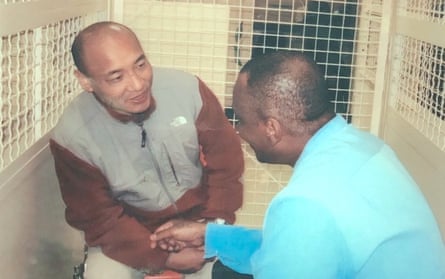

Jarvis Masters, 61, has been in prison for 42 years, sentenced to death for a crime he has long said he did not commit – sharpening a weapon used by someone else to kill a prison guard. Witnesses who named him have recanted, and others have confessed to making the weapon, prompting widespread outrage about the case and support for Masters, including from Oprah Winfrey. With his lawyers and loved ones in the Bay Area, a short drive away from San Quentin, he’s grown increasingly anxious about the prospect of being transferred, possibly hundreds of miles away to remote facilities difficult to access.

“My life depends on communication with my attorney,” he said by phone. “A lot of people’s sanity is hinged on that – being assured that their attorneys are doing everything possible to bring some positive resolution to their case.” After living in a solitary cell for decades, he said, the idea of having roommates and losing privacy also concerned him.

“There’s no place where I won’t feel I’m on death row and innocent,” Masters said. “You can put me in a place with a new basketball court or where I can wash my laundry or walk into a chow hall without shackles, but I’ll still be thinking about my status. To say we’re going to give prisoners a right to be without hand restraints – I feel like my whole life is in hand restraints.”

On 17 March inside San Quentin, Newsom stood in front of incarcerated residents and suggested his Norway-style prison transformation could see death row turned into an “honor yard” focused on programming for residents: “We have to be in the homecoming business. It’s not just about rehabilitation … You want folks coming back feeling better.”

Norwegian prisons, which have been called the “most humane” in the world, have staff trained in social work, and incarcerated people have privileges, such as the ability to cook, private family visits and unlocked doors. It’s a far cry from San Quentin, which, while known for its arts programs and classes, is still an overcrowded, highly punitive American prison. And while Norway has no life sentences, in California, more than 5,700 people are sentenced to death or life without parole.

Some on death row hope that the transfers will bring them one step closer to leaving prison, especially as some state lawmakers push for reforms to undo some of the harshest prison terms. While individuals can be resentenced or have their death sentences overturned, it would require a major overhaul to enable mass resentencing, and repealing the death penalty as a form of punishment can only be done through a ballot measure.

CDCR and the governor’s office declined interview requests. A spokesperson for the governor pointed to Newsom’s comments in December saying that commutations for people with death sentences were “something that’s long been considered”.

Dana Simas, CDCR spokesperson, said in an email that it was possible some on death row could be transferred to other parts of San Quentin, but that housing placements would be made on a case-by-case basis related to an individual’s “security, medical, psychiatric, and program needs”. She said the transfer program would expand access to rehabilitative programming and job opportunities, which would allow people sentenced to death to pay restitution to victims.

There was no set timeline for the transfers to be completed, Simas said.

“Hopefully the powers that be will deem me worthy of a real second chance,” said Tracy Cain, 60, on death row since 1988. He is among the 40 death-sentenced people who went through the appeals process and had their death sentences affirmed by state and federal courts, meaning if a new governor resumed executions, he’d be at risk. While he would like to see his death sentence revoked, he said, he also fears the most likely alternative: “Life without the possibility of parole is a death sentence under a different name … When does the rehabilitation become as important as the punishment?”

Those already transferred off of death row said it was refreshing to be around people making plans for life after prison: “It gives us a little bit of hope,” said Rogers. “I’m in an environment where people are studying for parole hearings to go home. People are packing up and leaving to go to the streets, and that’s kind of exciting.”

Thomas said he had since had the chance to participate in self-help groups and now was a facilitator of a class where men process their traumas and engage in group therapy: “There’s some sense of normalcy as opposed to being just locked in a cage and regarded as trash and unworthy of anything. In a San Quentin cell by yourself, you keep all this stuff to yourself. But once I was in this circle and going through this class, I learned to open and share.”

Some of the men in the group are driven by their coming parole board hearings. Thomas, however, has had to find his own motivation: “This change I’ve made in my life, this growth, becoming a better person, it’s solely for me. That’s how I approach it. A lot of guys do this to be able to get out. But I don’t have those opportunities as of yet.”

Doolin’s mother, Donna Doolin-Larsen, said the uncertainty of the transfers weighed on them, but that her son tried to shield her from the darkest parts of death row: “Keith handles a lot on his own that I would never know happens. But Keith has always been positive. Anybody who has ever visited him has never seen him down. But that doesn’t mean he’s not down behind closed doors.”

Doolin said the hardest part of his incarceration was that he couldn’t be there for his loved ones when they were struggling – missing funerals and unable to help his 80-year-old mother through her worsening health problems. “Being physically handcuffed daily – that hurts,” he said. “But being physically helpless to help my family, that hurts the most.”

For now, Doolin’s holding on to hope that his conviction will be overturned, and that when he leaves San Quentin, he’ll be walking free, not heading to another prison.

He fantasizes about having a meal at a dinner table with family, using real silverware and plates, and drinking water with ice cubes. He dreams of living in an area with lots of grass, trees and open terrain. And he looks forward to never again wearing the blue color of prison uniforms.