Russell Metty's four-decade span as one of Hollywood's top cinematographers was highlighted by his Academy Award for Best Color Cinematography on Spartacus (1960). That honor, however, only scratches the surface of his career.

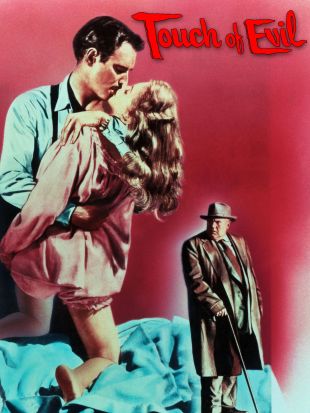

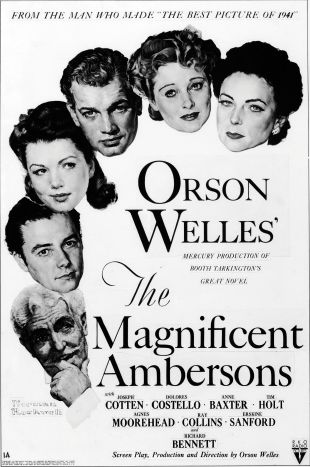

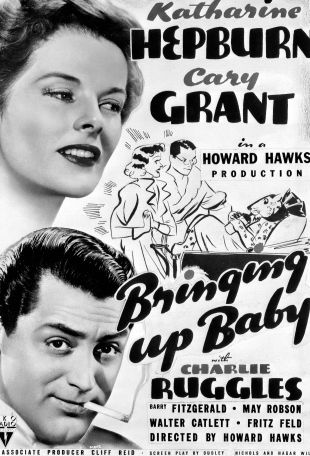

Metty was born in Los Angeles in 1906, just in time to reach his teens as the film industry entered its own adolescence, and to join it during the peak of the silent era. He entered the movie business as a lab assistant during the 1920s and later served as an assistant cameraman and second camera operator at RKO during the early '30s, working on such films as Symphony of Six Million and The Penguin Pool Murder (both 1932). He made his debut as a cinematographer in 1935 with West of the Pecos and is credited in some sources as having worked with Joseph August on George Cukor's Sylvia Scarlett. Metty subsequently shot Howard Hawks' Bringing Up Baby in 1938. He became known as a highly gifted and inspired lighting cameraman, inventive in his use of crane shots and in the most subtle aspects of night and twilight shooting. He was a consultant on Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941, photographed by Gregg Toland) and worked under Stanley Cortez on The Magnificent Ambersons the following year. He was Welles' later choice as cinematographer on both The Stranger (1946) and Touch of Evil (1958), and remained at RKO to shoot such titles as Hitler's Children and Tender Comrade. In the mid-'40s, Metty worked on such independent productions as The Story of G.I. Joe and, after a time associated with films released through United Artists, landed at Universal, where he worked for the next two decades.

Metty moved into color cinematography with results every bit as impressive as those he'd achieved in his black-and-white period. When he started with the company, Universal was doing film noir and lower-budget costume and Western vehicles, but as its output became bolder, slicker, and glossier, he moved up quickly, shooting such high-profile Douglas Sirk films as Magnificent Obsession (1954), Written on the Wind (1956), Imitation of Life (1959), and remained on the cutting edge of filmmaking when he returned to work with Welles -- and in black-and-white -- on Touch of Evil. In terms of the prominence of the movies on which he was assigned, Metty reached the pinnacle of his career with Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus, for which he won his only Oscar (though he was nominated by the Academy again for 1961's Flower Drum Song), and on which he employed all of the technical expertise he had acquired over the previous 30 years. Metty's photography -- as much as Howard Fast's story, the screenplay, and Kubrick's direction -- is a key reason why Spartacus stands apart from virtually all of the Hollywood costume epics of its era. Most of the movies on which he worked from the mid-'50s also demonstrated his inspired use of anamorphic photography (the other major change in shooting from that era) in such processes as CinemaScope, Techniscope, and Panavision.

Metty's total technical and artistic skills were all on view -- as brilliantly as they'd been with Welles and Kubrick in 1958 and 1960 -- in his shooting on Don Siegel's Madigan in 1968. The oblong Panavision frame didn't stop him and, in fact, enhanced his ability to keep all of the images mobile and in seemingly effortless flux, capturing the claustrophobic surroundings of New York's tenement building in one shot and the sweep of the city's skyline in another. Although the movies he photographed during the 1960s and '70s were less impressive as films -- for every movie like The War Lord (1965), there were two along the lines of Madame X (1966) or How Do I Love Thee (1970) -- Metty never stopped adapting to the times or requirements for his jobs. Considering the amount of time he spent as part of the traditional Hollywood system, he proved astonishingly capable when shooting moved off the back lots and onto America's streets in the late '60s and early '70s, and he got phenomenal results photographing films such as Madigan in New York City and The Omega Man (1971) in Los Angeles. Metty finished his career doing primarily television work in the early to mid-'70s, including such series as Columbo and The Waltons. He died in 1978.