Serco used to be the biggest company you had never heard of. For three decades it grew in the borderlands between the state and society, the government and us. Its name stands for “service company” and Serco, which combined great ambition with a desire to be unseen, wanted to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time. It was as much a formula as a company: a way to implement outsourced public services on behalf of governments, but with the elan of a restless entrepreneur. It didn’t matter what the service was, where it had to happen, or to whom it was delivered. Serco started out operating radars in Yorkshire and traffic lights in London, but it came to work with schoolchildren and doctors, commuters and prisoners, pilots and refugees. It was designed to be limitless, and to grow for ever. At its peak, Serco had a workforce of 125,000, contracts on four continents, and revenues of £5bn. But in 2013, the formula faltered. Everybody heard about Serco, and the roof fell in.

The trouble started in the spring. A young civil servant, a fast-streamer in the Ministry of Justice, noticed strange numbers in the documents submitted by Serco and G4S (another large outsourcing company) as the firms prepared to renew two electronic tagging contracts that they held with the British government. Since 2005, the two companies had earned around £700m from monitoring thousands of criminals, suspects and recently released convicts via tracking devices attached to their ankles – a practice introduced by the Home Office to reduce prison costs in 1999. But according to the junior civil servant, whose findings were initially dismissed, they were overcharging the state.

The paperwork that embodies government outsourcing, the physical contracts themselves, tells you a lot about how vexatious the whole business is. Capturing exactly what the state wants done on its behalf – the running of a railway system, the rehabilitation of prisoners – can produce dizzying piles of paper for even mundane tasks. The government chivvies its contractors to do a thousand things correctly. Private companies seek to minimise their risks, and ensure a quiet profit at the end of the day. Everyone covers their arse furiously. The documents that emerge are hundreds of pages long, dense with KPIs (key performance indicators) and SLAs (service level agreements) and kept secret from the customers – us, the public – whom they are supposed to benefit. Once they are signed, they are rarely looked at again.

For the tagging contracts, it was decided that it was up to the crown, and not G4S or Serco, to decide when individuals should be fitted with a tag. This made sense, but it gave rise to an aberration. The companies came to regard monitoring cases as open or closed on the basis of letters they received from the courts and prisons, rather than anything to do with the physical fitting or taking off of tags. They billed the state until they had a document telling them not to, even if the subjects had died, disappeared or were no longer wearing a tag. G4S’s computers were set to continue billing to 2020; Serco’s to the year 3000.

Over the years, letters got lost, notifications were not followed up, and these cases accreted. No one checked the contract. Serco charged the Ministry of Justice £15,500 for five years of monitoring a suspect they never managed to locate in the first place. When the anomalies came to light in 2013, they showed that the companies had invoiced the taxpayer for millions of pounds’ worth of nonexistent work. “You are charging us for people who are dead,” as one Cabinet Office official involved in the subsequent showdown told me. “I don’t care if the contract says you can, it is a wrong thing.” Serco and G4S were banned from bidding on new government work for six months, while investigations into their other contracts were carried out. The Serious Fraud Office got involved.

The revelations hit Serco particularly hard. The British central government provides a quarter of its global revenues. The idea that the company was ripping off its most important customer – “the goose that laid the golden egg”, as Serco executives sometimes called it – panicked investors. The share price slid. Then, in late August, the Ministry of Justice announced that the police were looking into “potentially fraudulent behaviour” on a second Serco contract: this time a £285m deal to transport prisoners to and from court in London and East Anglia.

A sense of crisis enveloped the company. Investors, politicians and the press connected what had previously been isolated controversies – in 2012 the Guardian revealed that Serco had altered statistics and mismanaged an out-of-hours healthcare contract in Cornwall – into a pattern of failures and dishonesty. For those already suspicious of Britain’s outsourcing complex, Serco came to represent everything that was wrong with it: anonymous, omnipresent, and playing us all for fools. In the space of five months, £500m was wiped from the company’s stock market value. On 23 October, Chris Hyman, the company’s chief executive – a charismatic South African who had been at Serco since it was founded – resigned. “The best way for the company to move forward,” he said, “is for me to step back.” (Hyman did not respond to requests for comment .)

Internally, Serco reeled. The company had always exuded a moral confidence that was unusual in an industry best known for cost-cutting. Hyman was an evangelical Christian. He tithed, donating part of his salary to his local Pentecostal church, and fasted once a week. Employees were rewarded for “living Serco’s values” and managers were given “commitments” rather than budgets or financial targets to meet each year. The tagging scandal cast all that in doubt. “Serco’s ethical compass needed to be reoriented,” said Alastair Lyons, the company’s chairman at the time, who was in charge of finding Hyman’s successor. Over the course of the winter, the board came to believe that they had found the man to do it, and on February 28 2014, Serco appointed its new chief executive, Rupert Soames, on a pay package worth more than £2m a year.

Soames, who is 56, is regarded as one of Britain’s most capable businessmen. Before taking the job at Serco, he ran a Scottish company called Aggreko that makes diesel generators and supplies temporary power projects around the world. Soames joined Aggreko in 2003, after its previous chief executive was killed in a car crash, and led the firm through an impressive decade of growth, during which its profits, sales and workforce had multiplied many times over.

Whether he likes it or not, however, Soames also stands for something else. Choosing him was an opportunity for Serco to revive itself at the well of the British establishment. Soames’s eldest brother is Sir Nicholas Soames, a former Conservative defence minister. His father was Sir Christopher Soames, an ambassador to France and the last governor of Rhodesia. His mother, Mary, learned to swear while commanding an anti-aircraft battery in Hyde Park during the blitz. His grandfather was Winston Churchill.

Merely being around Soames – who is bulky, self-assured, and often speaks in similes that involve things like spaniels, grandmothers, rhododendrons and oysters – evokes sensations of an earlier, stronger Britain. Sentences come heavy with italics and euphemism, sometimes both. (I once heard Soames characterise the royal family as “that side of things”). His default mood is one of loud amusement. At Oxford, where Soames was president of the union, he spent most of his time spinning records. He drove down to London twice a week to play the decks at Annabel’s, and brought the beats to Charles and Diana’s engagement party in 1981. He might have been the poshest DJ in the world. He loves control, and he loves to lead. When Lyons met Soames, he perceived “a streak running through him of service and duty”, and he is not the only one. “It is something almost military,” an old friend, who has known Soames since university, told me. “It cascades down from his grandfather. He likes to look over his shoulder and see 10,000 people marching.”

Soames himself hates this kind of talk. He abhors swanking of any kind, and bristles at casual references to his background. “Somebody asked me: ‘What’s it like being Churchill’s grandson?’” he said to me once, putting on a nasal voice to indicate that this was an annoying question. “And I say, I have got no fucking idea because I have never been anything else.”

Still, he possesses an innate relish for the work of the state, what he calls “the public service bit”. Soames went for the Serco job on the day he heard that Hyman had resigned. And despite working in the private sector all his life, there is a sense that in the unglamorous world of public sector outsourcing – thankless, complex and human – Soames has joined the family tradition at last. “Rupert,” as his older brother Sir Nicholas, put it, “has the architecture.” Since taking over at Serco, he has begun to replace the company’s corporate speak of “value creation” and “market opportunities” with a more plain-spoken dialect of people and their problems. “This is called government. This is called public affairs,” Soames said once, when we were discussing Serco’s high-profile contracts to detain asylum seekers in the UK and Australia. He could have been speaking at prime minister’s questions.

For all the assurance that he has brought, however, and the shadow of his forefathers, no one knows whether Soames can save Serco. About a month after he got the job, he went to see Margaret Hodge, the chair of the House of Commons public accounts committee, parliament’s main watchdog over the UK’s £120bn outsourcing industry. “He said he was going to turn it all around,” she told me. “All the gossip to me was that he was going to go bust.”

The company has staggered from month to month. Since 2013, Serco has issued three profit warnings, raised £715m from its shareholders to meet its debts, and announced losses of more than £1bn. Its share price has traced a long and dismal totter, from 682p in July 2013 to 126p now – a decline of more than 80%. In the City, many analysts doubt that the company can ever recover. “If there is one person who can turn around a sinking ship it is probably Rupert,” one told me. “But he wouldn’t be the first good manager to meet a bad company.” For most of us, however, the questions are different. How did Serco get so big in the first place? Is it worth saving at all?

Hiring private companies and self-interested individuals to deliver public services is an old, if charged, arrangement. For centuries, kings and queens had no option but to contract out courts, taxes, roads, prisons, to nobles and business folk. The spectre of “old corruption” – a deadening lattice of sweetheart deals, public offices traded for personal profit – was a permanent fixture at British elections until the mid-19th century. The emergence of the welfare state and large government bureaucracies helped to banish this tension, and to incubate popular distrust of private actors operating in the public realm.

The rise of modern government outsourcing has its origins in business theory. In 1937, Ronald Coase, a young left-leaning lecturer at the London School of Economics, published a short paper called The Nature of the Firm, in which he considered why companies contracted out some of their functions, but did others in-house. “Why is not all production carried on by one big firm?” he asked. Coase developed the idea that organisations are constantly searching for a balance between the “transaction costs” involved in hiring external suppliers to do certain tasks and the increased potential for mistakes, waste, and the “decreasing returns to the entrepreneur function” if a company tries to do everything itself. After the war, Coase, who later won the Nobel prize for economics, moved to the University of Chicago. He gave up on socialism and his work became influential among a new generation of free-market theorists keen to question the preference of large organisations – particularly governments – to direct their own affairs rather than seeking the skills and competitive pricing of the open market.

They first made the case for outsourcing in bins. During the gloomy, stagnant days of big government in the 1970s, economists crisscrossed the US, Europe and Japan to find out what happened when cities hired private companies to collect their rubbish. It was a no-brainer. In the US, Steve Savas, a champion of privatisation who later joined the Reagan administration, found that New York’s sanitation department only worked half the time. A team in Japan recorded savings of 124% when towns outsourced their refuse services. Private companies were more productive and had better trucks. In the mid-1980s, the Institute for Fiscal Studies carried out a survey of 309 British councils and found average savings of 22%, and no reduction in quality, when they used private dustbin men. This evidence became an important basis for the 1988 Local Government Act, which introduced competitive tendering for around £2.5bn in local services in the UK, and launched the British outsourcing market. Nicholas Ridley, Margaret Thatcher’s environment secretary, dreamed of town councils that met once a year to sign a bunch of contracts, and then went home again.

Serco was ready and waiting – although it wasn’t called Serco yet. Until 1987, it was RCA Services Ltd, the British arm of a fading American conglomerate. The Radio Corporation of America had grown to subsume everything from hire car companies (Hertz) to publishing houses (Random House). Its electronic services division in the UK was a small, modestly profitable corner of the business. It made money maintaining two very large military facilities that it had built for the British government: the nation’s ballistic missile early warning system, at RAF Fylingdales on the North York moors; and a secret state-of-the-art radar at Orford Ness, the UK’s atomic weapons research base in Suffolk. When Thatcher extended her outsourcing campaign to central government departments, RCA’s deals with the Ministry of Defence became prototypes for civil servants across Whitehall.

The managers at RCA paused to reconsider their own work as well. They thought of themselves as scientists and engineers – Richard White, one of Serco’s founders, who joined RCA in 1970, had trained as a chemist – but more than half of the company’s 700 employees at RAF Fylingdales had more routine jobs. They looked after the grounds, the post, the canteen. The art, it turned out, was in running the people, not the radar. “We reinvented ourselves as a management organisation,” White told me. In 1984, RCA won the MoD’s first official outsourcing contract, to operate a big supply depot at RAF Quedgeley, in Gloucestershire. “We had never run a store in our lives,” said White. But that didn’t matter. The RAF’s storekeepers, who transferred into the new company, knew how to do that. Three years later, White helped to lead a management buyout, and RCA Services Ltd became Serco.

The early years of Serco were characterised by a sense of limitlessness. There was no end to what governments could, in theory, contract out. “It just felt like the whole world was opening up,” White told me, “and we seemed to have the right formula to meet it.” The company assumed the shape it more or less holds today – a small head office overseeing hundreds of Serco outposts, teams of 30 or 50 or 100, out running some corner of what used to be a state concern: the display boards on the M25, a prison in New Zealand, a road tunnel in Hong Kong. From the start, contract managers were encouraged to think of themselves as their own bosses, with their own businesses to run.

Back at headquarters, a team of 20 or so, led by a group of founding directors known as the “gang of four”, bid for new work, and reimagined the future of public services. The company set up a thinktank, the Serco Institute, which studied the outsourcing of the past – 18th-century contracts to transport convicts to Australia – and public services overseas. The gang came to see the border between the public and private sector as a cultural artefact: strongly held, but always shifting. “Just a movable line,” according to White. In Denmark, for instance, emergency services have been privately delivered since the 1920s, but care for the elderly remains overwhelmingly a state concern. In Sweden, the opposite is true: large-scale outsourcing of care services began in the 1990s, but nobody would dare touch the state’s fire engines or ambulances.

Serco’s confidence, research and omnivorousness distinguished it from its rivals. Rentokil did cleaning; G4S did security; Capita did IT; Serco did anything and everything – and its panache in the bidding process meant that it often beat out competition from specialist firms. For a long time the company had a formidable “win rate”, securing 70% of the contracts it bid for.

In 1989, Serco had 3,000 employees and revenues of £59m. Ten years later, it had 27,000 employees and revenues of more than £800m. By that time, New Labour had loosed the second great wave of outsourcing across Britain’s public services – although now under a rubric of improving choice and value for money for citizens, rather than the overt Thatcherite goal of dismantling the state.

Again, Serco was on hand to pick up the work. The company got involved in privately financed hospitals, prisons and military facilities; took over failing local education authorities in Bradford and Walsall; and won its first major immigration contract, to run the Yarl’s Wood immigration removal centre, in 2006. Serco sent managers abroad, to win transport, science and prison work in Australia and the US. For a while, the company had 47 staff in Antarctica. It administered Canadian driving tests. It became responsible for setting Greenwich Mean Time. The graphs in its annual reports – revenues, profits, dividends – resembled endless staircases, disappearing upwards.

Serco became an international business that claimed to have squared the circle of public service and private gain. In 2005, its revenues leapt by almost 40% to £2.2bn. Hyman was the perfect frontman. He made success sound inevitable. “We can quadruple and it won’t affect the model at all,” he told Management Today in 2007. “We could become a multinational with hundreds of thousands of workers and it still wouldn’t matter.”

For this article, I spoke to nurses, porters, cleaners, swimming teachers, train managers and prison guards who worked for Serco, and at its best, they described a company that made steady profits delivering public services with more care than the state ever did. “I made more of a difference than in any other period of my life,” said Lee Barnes, a former prison governor who joined Serco and saw the company give prisoners keys to their cells and guards being addressed by their first names. “They encouraged us. They allowed us to do that.” Another former employee, who had been a trade union official, was proud that Serco has never faced a strike on its contracts. “They had this mindset that public sectors were good people surrounded by bad systems,” he said. “It was a brilliant paradigm.” In March 2013, two months before the tagging scandal broke, Serco reported revenues of £4.9bn and profits of £302m, the highest in the company’s 25-year history.

When Soames started work at Serco, he had a clear idea of what he expected to find. “Big reputational damage,” he told me, “but fundamentally the business would be very sound.”

Within a week or two, however, he sensed that Serco was in a much more fragile state than it appeared. The company’s sales forecasts for the year were unravelling, and its profits were declining at an alarming rate – in a way that far exceeded the expected impact from the tagging scandal and negative headlines of 2013. On 1 May, officially his first day in the job, Soames issued a profits warning and launched an emergency fundraising of £160m to keep the company ahead of its debts. “It became obvious,” he told me, “that the world was falling out of its bottom.”

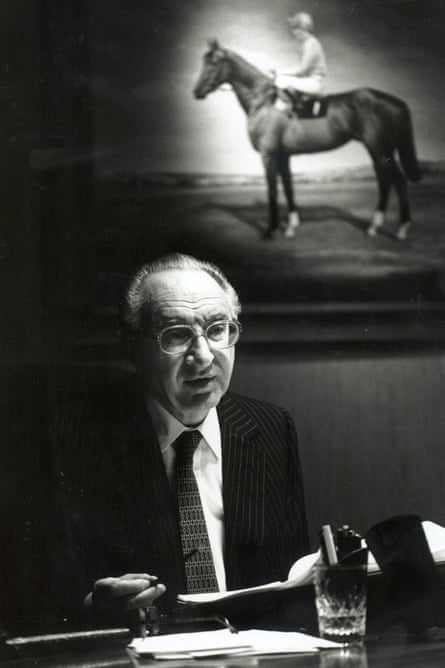

Soames spent the first 16 years of his career at GEC – the General Electric Company plc – the British electronics giant, and came to revere its legendary and prickly chief executive, Arnold Weinstock. At its height, GEC consisted of 180 companies and had a workforce of 250,000. For three decades, Weinstock ruled this empire from a set of dimly lit offices in Knightsbridge decorated with pictures of racehorses. The key to the operation was a set of standardised monthly reports filed by every GEC business: eight ratios (profit margin, staff turnover and so on) on the first page; raw figures on the second page; a written commentary thereafter. Weinstock spent hours each day scouring these documents, covering them in red ink, picking up the telephone, firing people if necessary. At the end of the day, he made a point of switching the lights out himself.

Soames has replicated GEC’s reporting system wherever he has worked. (He has two photographs in his dressing room, one of Weinstock, the other of his father.) When he arrived at Serco, the first thing he asked for was a copy of the monthly accounts. They did not exist. (Because Serco’s contracts are long-term – most of them last between three and seven years – the company had only ever collected its financial data every quarter.) Next, Soames asked to see a database of the company’s order book of 700 contracts, showing which ones were in profit, and which were loss-making. That did not exist either. As the incoming chief executive, part of Soames’s job was to reassure a demoralised workforce, but he was taken aback by how little Serco knew about its own business. “When you see things that may be deeply shocking,” he told me, “you can’t show your shock.”

In the meantime, the bad news kept arriving. Experienced staff were jumping ship. Serco’s damaged reputation meant it was losing outsourcing bids that it would normally win, and there was a troubling drip-drip of allegations from some of the company’s most sensitive contracts. These included Yarl’s Wood, where Serco detains female asylum seekers on behalf of the government. Its staff have been accused of sexual abuse and 10 guards were fired last year. “I was counting my days on the basis of how many really, really shitty bits of news happened a day, and it used to be four,” said Soames. “If I hadn’t had my four bits of bad news, I knew something was wrong. I knew there was something I didn’t know.”

The air slowly cleared. It took two months to build the contract database. (Soames is a nut for spreadsheets and databases: he likes to re-enter the digits himself.) He discovered that Serco operated in 38 different markets, from dog wardens in Birmingham to air traffic control in Baghdad. He hired his former finance director from Aggreko, Angus Cockburn, and brought in 40 accountants from Ernst & Young to perform a triage on Serco’s global order book, looking for hidden risks and possible losses. Soames adopted a voice from Monty Python when he described this process. “Bring out yer dead,” he hollered. “Suddenly, these bodies started flying out.”

Soames came to see that Serco’s finances were under attack from three different directions. First, there was the continuing fallout from the tagging dispute of the previous year. (In the end, Serco paid back £68.5m for the tagging debacle, and agreed to forgo any future profits on its prisoner escort contract. The Serious Fraud Office investigation into the tagging contract continues.) More broadly, however, the company had not negotiated the economic crisis anywhere like as well as it had claimed. The arrival of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition unleashed Britain’s third great wave of outsourcing since the 1980s – between 2010 and 2015, the industry doubled in size from £64bn a year to £120bn as new health, probation and benefit services hit the market – but many of Serco’s new contracts were hastily designed and bid for, and barely breaking even.

The main reason, according to several former directors I spoke to, was a subtle but noticeable shift in the company’s priorities that began in the mid-2000s. Under Hyman, Serco became steadily engrossed by its own financial performance. He set the company an internal goal of joining the FTSE 100 list of the UK’s largest companies, which it achieved in December 2008. During the depths of the global economic downturn, in 2010, the company then set itself a new goal – to become “the world’s greatest service company” – and issued ambitious forecasts for revenue growth and profits by 2012. Chasing these targets in the face of austerity in the UK and the federal shutdown in the US meant expanding into new areas, such as clinical healthcare and large-scale private outsourcing, which Serco had avoided in the past.

A former director, who had left Serco and rejoined the company around this time, found many of his colleagues increasingly pressurised and alienated by a culture almost entirely focused on the bottom line. The Serco Institute was shut down. So-called “black hat conferences”, at which hardened public service managers used to be invited to challenge the optimistic bidding assumptions made by the financial teams at headquarters either did not take place, or were formalities, dominated by bid teams. “It was all these commercial guys, just modelling it without any notion of what would happen,” the director told me. By 2014, Serco was managing to lose money on an outsourcing deal with Hertfordshire county council – the kind of work it had done for a generation.

More worrying, even, than either of these, Soames discovered that scattered throughout its books, Serco also had a small number of contracts that put it on the hook for potentially unlimited losses. If you spend time with people in the outsourcing industry these days, the subject most of them want to talk about is “risk transfer”. As well as creating money-making opportunities, novel forms of outsourcing contracts in the last decade have also, on occasion, left private companies exposed to extraordinary levels of financial damage and public loathing. Even small miscalculations, or unexpected events, can carry vast consequences. Serco’s rush to growth made it more vulnerable to these risky deals than most, and from the moment he arrived at the company, Soames began to hear more and more about the 14 Armidale patrol boats that it had agreed to supply to the Australian Navy in 2004.

The contract was simple enough. Serco had to make the patrol boats available for a total of 3,600 operating days a year. If they broke down, it was Serco’s problem. In the early years, the Armidales made money for Serco, but from 2008 onwards, Australia faced a sudden increase in asylum seekers attempting to reach the country by sea. Between 2007 and 2012, the numbers leapt from 148 to more than 17,000, and the Armidales were the navy’s chosen means to intercept the migrants’ fragile boats as they approached the coast. The patrol boats were driven harder and faster than ever before. They developed corrosion and cracking in their hulls. Amazingly, for several years, Serco was able to offset any losses from the patrol boats because it also had the contracts to detain the asylum seekers in immigration camps once they landed in Australia. For this work, it was paid on a volume basis – per asylum seeker. The surge in refugees made these contracts the most profitable in Serco’s entire global portfolio, bringing in £450m in 2013.

But from the July of that year, a dramatic change in Australia’s immigration policy – under which all “illegal maritime arrivals” would now be detained in Papua New Guinea – meant that Serco faced a double blow: fewer asylum seekers came, and the Armidales still required expensive maintenance. To add a further, mind-altering twist: it was possible that some of those immigrants would now head for Britain, where Serco also had contracts to provide temporary accommodation to asylum seekers – but because it had negotiated those deals poorly, it was now losing money on every person that it housed in the UK. “It is called falling off the swing,” said Soames, when he tried to explain all this to me, “and getting hit on the back of the head by the roundabout.”

There are times, when considering Serco, that it begins to resemble Milo Minderbinder’s syndicate, M&M Enterprises, in the novel Catch-22, which starts out trading melons and sardines between opposing armies in the second world war, and ends up conducting bombing raids for commercial reasons. If you are going to make money in conflict, or the messy affairs of human life, Milo reasons, you might as well play as many sides of the action as possible. “In a democracy, the government is the people,” he argues. “We’re people aren’t we? So we might as well keep the money and eliminate the middle man.”

Last autumn, Soames and Cockburn concluded that a handful of contracts – led by the Armidales, and the deal to house asylum seekers in the UK – could cost Serco up to £500m in losses, which posed a mortal threat to the business. They began a series of weekly meetings with officials at the Cabinet Office to brief them on the company’s financial state. According to Soames, these conversations prompted the government to develop a contingency plan in case Serco went bankrupt.

On 10 November, Soames announced a new strategy for the company: it would be simpler, and smaller, and serve governments only. The moves into healthcare and business outsourcing were to be abandoned and sold off. (In 2015, Serco expects to have revenues of £3.5bn, around two-thirds of what it was making at its peak.) The company would sell its recent acquisitions, shedding tens of thousands of employees. Soames also revealed the scale of Serco’s losses for the first time: a total of £1.3bn – the equivalent of its last 20 years of profits combined.

Soames and I spent several afternoons together in May and June, talking about what had gone wrong at Serco. Often we met in his seventh-floor office near Victoria. He always wore the same uniform: dark suit, braces, specially tailored blue herringbone shirts with the words “Serco – and proud of it” sewn into the right side of his chest. Since the tagging scandal and the misreporting of statistics on its Cornwall healthcare contract in 2012, Serco has also been stripped of its responsibility to sterilise medical equipment at Fiona Stanley Hospital in Perth, western Australia, and has been criticised by human rights groups for its treatment of asylum seekers in both Australia and the UK. (In March, the company launched an independent review, led by a former barrister, Kate Lampard, of conditions at Yarl’s Wood.)

One subject we kept returning to was whether the company’s fixation with growth – its compulsion, publicly and internally, to meet the revenue “commitments” set by its top management – had contributed to its ethical and performance failures. Soames’s essential argument was that the two were unrelated. “I think you can construct a story linking the pressure for financial performance to those ethical breaches. I personally think that is wrong,” he said.

But Soames’s language wavered. Sometimes when we talked, Serco’s profit targets and the level of care it put into its public services existed in “parallel universes”. Other times there was “a tenuous connection”. Once Soames acknowledged that “one made the other worse”. When I told him about a Serco manager I had spoken to in Cornwall, who described staff in tears every day in early 2012 as they contended with unrealistic financial demands from head office and a healthcare contract they were struggling desperately to meet, he said: “I don’t know. I wasn’t there.” He did not pretend that the question was straightforward. “I don’t go to bed at night thinking, ‘Oh well, sorted that one then,’” he said.

The restless dynamic between corporate profit and public service lies at the heart of why many of us feel anxious about outsourcing. The dice seem loaded from the start. People at Serco used to puzzle over this mistrust. “I think the public is divided,” one of the company’s former board members told me. We hate waste, he explained. We tend to approve of competitive tendering. We acknowledge the existence of good, vocationally driven private actors in the public realm, like GPs. “On the other hand,” the board member went on, “people are deeply suspicious of the profit motive. They know how powerful the profit motive is and they worry if you get the incentives wrong that will produce horrible consequences.”

Outsourcers also threaten us because their growth entails the dismantling of something that was familiar. Public sector monopolies may not have always been effective, but at least they came with a story, an implied commitment to a common cause. They were, in some inescapable sense, ours. By contrast, the rise of the UK’s public services industry – which now employs more than a million people and is the world’s second largest, after America’s – is an experiment that has been conducted largely without a narrative, and whose principal agents are large companies that belong to their shareholders. They are, in some inescapable sense, not ours. (Serco’s largest investors, by way of example, are hedge funds, American value investors and the Singaporean government.)

Market forces, transaction costs and Coasian bargaining theory do not care if we believe in them or not. Politicians do not help much. They do not celebrate or explain outsourcing, even as the consensus solidifies about the “mixed economy” required to deliver Britain’s public services to an ageing population unwilling to pay higher taxes. All the main parties are signed up. They just don’t like to talk about it. Even Nicola Sturgeon and the SNP are Serco customers: they unveiled the company’s new contract to run the Caledonian Sleeper service in March. The experiment proceeds. The stakes get higher.

* * *

Since March, and the conclusion of Serco’s latest fundraising from its shareholders, Soames has been able to get out and about more. He tries to visit one of the company’s contracts every week. On a recent Friday morning, he picked me up from a station near where he lives with his family in Buckinghamshire (Soames keeps a small mixed farm: “Twelve Sussex cows, plus a bull”) and drove us to RAF Benson, in Oxfordshire, where Serco trains helicopter pilots for the armed forces in computer simulators. On the way, we talked about his childhood. Soames spent many days at Chartwell, the Churchill family home, as a young boy, and remembers being dandled on the great man’s knee. The legacy, more than anything, is of industry: all those books, all those paintings, all those wars. “It was an immense thing,” he said, “this prodigious work ethic …” These days, Soames works seven days a week, five or six hours on Saturdays and Sundays. His staff wake up to emails and memos – noodlings – time-stamped at 6am, or 10pm.

At the helicopter base, Soames busied himself in the arcana of outsourcing. At RAF Benson, where Serco earns around £4m a year on a contract it has held since 1997, the company is trying to supply the same amount of flight training to the MoD with fewer pilots. Soames spent the morning talking to the contract manager about shift patterns and the cost of helicopter earphones. He tried out the flight simulator, rejected his instructor’s suggestion that he use the autopilot, and crashed in a field. “And it was all going so swimmingly,” he said. After the screen froze, Soames asked to be taken upstairs to see the servers. He stood with his hands on his hips, facing a bank of humming machines, as if he might find the glitch with his own eyes.

At lunchtime, the Serco staff gathered in a meeting room and ate from a cold buffet. Everywhere Soames goes in the company, he gives a stump speech about what went wrong, and how he is trying to fix it, which lasts about seven minutes. Then he asks for questions. Consciously or not, Soames often slips in military references when he speaks. At an in-house awards ceremony in May, he compared the company’s shareholders to Von Blücher’s cavalry at Waterloo. He always closes with the same words: “Someone once said, and I can’t think who: ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.’”

At RAF Benson, the pilots chuckled, but the conversation quickly turned serious. They wanted to know what Soames was doing to stop the bean-counters from taking over the company again. They wanted to know if the political tide might turn against outsourcing one day. “People don’t want to pay more tax,” said Soames. “It ain’t going to happen.” Towards the end, one pilot with a direct manner told Soames they had been treated like “toilet cleaners” by the previous management and asked about the estimated £4m pay-off that Hyman received when he left. For a moment, the room went quiet. “I have no problem with you asking the question just as you are going to have no problem with me not answering it,” said Soames. He spoke carefully. “I wasn’t involved. I wasn’t there, and you know what, I couldn’t give a damn. I intend to be different. And that is not to say the past was right or wrong, but I am not the same.”

Later, driving back to the station, I wondered whether we will look back on this moment, in the early 21st century – like we look back on the 1970s, or the 18th century – and be astonished by a single company doing so many things, in so many places, for and to so many citizens. Soames was on his way home to work for a few more hours. When you run a state within a state, there is always something demanding your attention. “It sounds pompous,” he said to me once, “but I feel that everything I have done previously was building up to do this.”

That afternoon, unusually, Soames’s voice carried an edge of tiredness. We pulled up at the station to wait for my train. I asked him if he thought he would ever miss this – the ongoing sense of crisis, a sceptical public, the darkness before the dawn – and he covered his face with his hands. “Fuck no,” he said. Soames slumped in his seat and he started to laugh. “Oh, God,” he guffawed. “Oh, God.” But wouldn’t he be bored, I said, if all was well in the world of Serco? “I don’t see that happening. I don’t see that for a long time,” said Soames. “I will get chucked out before that.”

Follow the Long Read on Twitter: @gdnlongread

This piece was amended on 2 July to correct an error: RAF Benson is in Oxfordshire, not Gloucestershire. This piece was also amended on 22 December to correct the title of Ronald Coase’s short paper published in 1937: it was called The Nature of the Firm, not The Theory of the Firm.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion