Deviation Actions

Description

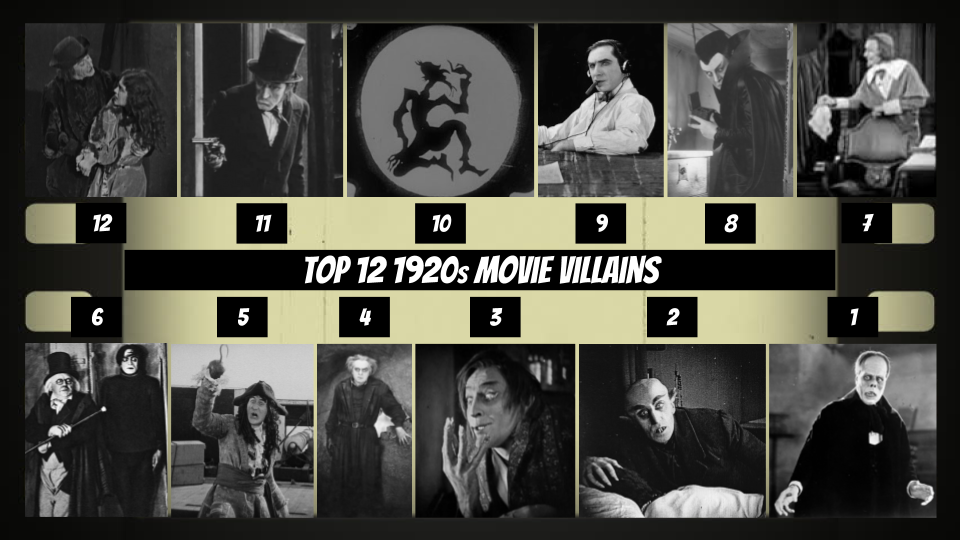

When I started doing this series of lists of movie villains per decade, I began with the 1930s. However, I always meant to go back and take care of the 1920s, I just didn’t know enough films from that period to really properly fill a list. Well, I’ve now seen more than enough, and I think the time has come to get on track there!

In my opinion, the 1920s is when movies really started to BE movies. Keep in mind, the motion picture was invented in the late 1880s, and the first proper films didn’t really happen until the early 1900s. As a result, for the two decades prior, movies were usually more about the novelty of their mere existence; story, characters, and performances came secondary, or even tertiary, to effects and the simple fact that they WERE motion pictures. Sure, there were exceptions, let’s not generalize TOO much…but I don’t think people really started to FOCUS on movies as anything beyond screwball comedies, started to see them as a serious means of presenting drama and masterful storytelling, until the 1920s.

With great stories came great villains. Try to remember a great movie villain from the time before 1920. It’s hard, isn’t it? But once you hit the big 2-0, you suddenly find yourself remembering some of the most iconic images of evil that still permeate our pop culture TO THIS VERY DAY. It has been a literal CENTURY since some of these characters, films, and performances first appeared, and they are STILL highly regarded. That, my friends, is POWER. So, we’re going to go back to the past and give some kudos to this oldies-but-goldies of diabolical devilry.

Now, keep in mind, I’m only counting feature-length movies here; shorts and serials will not be counted. Also, again, this is for the 1920s; anything prior to this date will not be counted. (Sorry, Ford Sterling; I still love ya.) With that said, here are My Top 12 Favorite Movie Villains from the 1920s!

12. Jehan Frollo, from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923).

To talk about Jehan Frollo from this film, I must first turn the clocks forward again to Disney’s take on the classic Victor Hugo story, which came out in the 1990s. There is a misconception that Disney was the first to reimagine Frollo in the way they did: in the Disney film, many may recall, Claude Frollo was a judge who was pretty much pure evil. This is in stark contrast to the book, where Frollo was an archdeacon and a much more sympathetic villain. The fact of the matter is that Disney didn’t really start this trend, they simply brought it to its critical mass. The Disney film, you see, owes much more to the earliest screen treatments of Hunchback, as made by Universal, rather than the book itself. And in these early adaptations, Claude Frollo was NOT the villain. In the 1920s and 30s, you see, featuring religious figures as evil characters was more than a little frowned upon (Disney may have had this problem, too, just because…well…Disney), so Claude Frollo was made out to be a good, wise, kind priest. Who, then, became the villain? His brother, Jehan. In the book, Jehan Frollo is a fairly minor character: a young man studying to BECOME a judge, and he’s far more nasty than his brother: a person who gives in wholeheartedly to his carnal and “worldly” desires and impulses without any repression or thoughts of morality. He acts as something of a parallel to his brother, Claude, who tries to repress all his hateful qualities and be a good person, but ultimately meets his downfall because he cannot deny the things he, as a man, truly wants. Both of the Frollo brothers are ultimately killed in the battle of Notre Dame. Early adaptations of the book to the screen saw a handy scapegoat in Jehan Frollo, and thus expanded his role, effectively combining him with his brother and making him the real villain of the story, while Claude, in turn, became a wholesome and relatively peripheral figure. Disney simply brought this concept to its natural conclusion by giving their Frollo Claude’s name instead of Jehan’s, and adding a religious bend to his passions and motivations. As portrayed by Brandon Hurst in the 1923 silent classic, Jehan is all of the things you expect Frollo to be, but without any sympathetic edge; he’s a smug, sadistic cad who thoroughly delights in his evil deeds. He makes no justification for his actions; in his mind, he lives for the moment, and takes whatever he wants now. Why worry about an afterlife if he can’t enjoy what the current life has to offer? He’s a fun, slimy antagonist…but my only problem is his very nature makes his whole relationship with Quasimodo sort of a nonsense. Jehan does something in the story that brews animosity between him and his young charge, true…but even before that, I wonder why Quasimodo was loyal to him and, furthermore, what possessed this guy to take him in. No real reason is really given; the movie indicates he simply did it out of the goodness of his heart…but after watching Jehan’s actions throughout the rest of the film, one automatically asks the question, “WHAT goodness was that, exactly?”

11. Professor Moriarty, from Sherlock Holmes (1922).

Played by Gustav von Seyffertitz. Starring John Barrymore as the titular master detective, this 1920s interpretation of Conan Doyle’s famous character veers more towards action-adventure than true mystery, but it’s still a worthy addition to the cinematic canon of Holmes. Part of this is due to the nemesis Holmes must face: his arch-foe, Professor Moriarty. The movie shows how Moriarty and Holmes first met, as the story starts off with a young Holmes actually being unable to catch Moriarty, before jumping ahead to years later, where new crimes force an older, more experienced Holmes to tackle his old enemy again, and this time come out triumphant. Seyffertitz plays a ghoulish sort of Napoleon of Crime; cold, aloof, and quick to the kill, who spends much of his time scowling and sneering as he goes about his business. Unlike many other versions, this one really doesn’t have much respect for Holmes, as the story instead plays out with Moriarty having to come to realize he is not as invincible as he thinks he is: after defeating Sherlock once, the Professor thinks himself untouchable…but in their second encounter, Holmes proves that he’s more than a match for the super-criminal’s fiendish genius.

10. The African Sorceror, from The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926).

Here’s a great example of why it was best I DIDN’T start with the 1920s when I began this series. When I did my first list for the 1930s, I claimed that Disney’s 1937 version of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was the first feature length animated movie ever made. Someone in the comments, not but a few months ago, revealed to me that I had been living a lie: Snow White as a first on many levels, but in point of fact, a few animated feature films had been made in Europe long before Snow White came around, all during the silent era. Unfortunately, most of those silent features have been lost to time, presumably destroyed and, sadly, never to be seen again. The oldest surviving animated feature is this one: “The Adventures of Prince Achmed.” The movie was the work of German animator and filmmaker Lotte Reniger; it features a unique form of stop-motion animation, inspired by Oriental shadow puppetry, with the style of the movie itself influenced, fittingly, by Persian and Indian paintwork. The characters are all made from paper and cardboard cutouts, which are then animated with incredible precision and fluidity, especially for the time, creating a beautiful contrast. Other forms of animation are present throughout the piece, too – such as minor inclusions of cel animation, and the use of powder or sand – usually to create the film’s special effects. The plot combines two of the Arabian Knights tales (“Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp” and “The Story of Prince Achmed and the Fairy Peri-Banu”) into one narrative, and tying the two stories together is the main villain: the African Sorceror. Apparently, the design of this character influenced the look of Count Olaf from “A Series of Unfortunate Events” (at the very least, he influenced the look in the elaborate closing credits sequence in the film version of the same, starring Jim Carrey), so that’s already a plus one in his credentials. As for the character himself: he’s your classic evil old wizard, who throughout the film tries all sorts of mad schemes to gain power and wealth, from marrying a princess to discovering a genie in a lamp. It’s indicated that his motivation for all his evil deeds is a twisted sort of spite: for all his magic powers, the Sorceror cannot change his overall appearance, and according to the film, “no one was as ugly as he.” His unpleasant demeanor has apparently led to him being shunned and hated by most of humanity, and as a result, he does cruel things seemingly just to get back at humanity. That’s a surprisingly halfway-sympathetic reason for the character to be as wicked as he is…though considering he can turn into other animals, one wonders if the only reason he can’t change his appearance is simply because he doesn’t know how.

9. Benedict Hisston, from The Silent Command (1923).

Your eyes do not deceive you: that IS Mr. Dracula himself, Bela Lugosi. Long before making a big splash as the Count of Transylvania, Lugosi made a living for himself in Hollywood in silent movies. I’ve seen a couple of Lugosi silent pictures, and in my opinion, his finest pre-Dracula performance comes from this WWI-set silent spy film. In this gripping action-adventure without sound, Lugosi plays Benedict Hisston…and with a name like that, in a film like this, he can only be – what else? – an enemy agent. Hisston is the leader of a group of foreign espionage operatives who plan to destroy the Panama Canal, and, in the process, wreck part of the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic Fleet. His nemesis is, bizarrely enough, also his ally, as the main protagonist of the film is one Captain Decatur – a navy intelligence officer who infiltrates Hisston’s organization of spies to try and stop the explosive scheme. The climax ends in a terrific brawl between the Saboteur and the Captain, where the usually refined and sly-as-a-fox foreign agent shows an unhinged edge as he violently attacks his enemy, beating him and trying to strangle him into submission even as the ship they are aboard rocks and rolls out of control on tumultuous seas. “The Silent Command” is not a subtle or even especially complex and smart picture, but as far as action melodramas of the silent era go, it’s pretty well done…and Lugosi’s performance as the black-hearted Benedict Hisston is a big part of what makes it work.

8. Mephisto, from Faust (1926).

Let’s talk about a little something called “German Expressionism.” Expressionism was an art from started in Germany that influenced basically all forms OF art: from traditional art (paintings, charcoal sketches, etc.) to theatre and film. It was born as a reaction to the wartime: the style reflected the horror and uncertainty Europeans felt during and after WWI, and moving into the time of WWII. Visually, it was a style that relied heavily on varying contrasts: harsh lights with long, heavy shadows; elongated curves accented by sharp, jagged points; asymmetrical angles that barely fit geometrical propriety and structure. The idea was to create an “otherworld” that was almost like a dream, or more often a nightmare; a place where the viewer could escape the realities of the cruel world around them, yet it still reflected the sense of dread and instability that the real world thrust upon them every day. While not created specifically for the medium of horror, Expressionism very naturally leant itself to that genre – it’s telling that a lot of non-horror pictures that were either made directly in the Expressionist style, or were simply influenced BY the movement, such as “The Man Who Laughs” and “Metropolis,” are often lumped together with movies that were intended to be horror pieces. In fact, in many ways, one could call the German Expressionist movement “The Birthplace of Modern Horror.” How fitting then that one of the greatest movies created within this particular mold was an adaptation of the timeless dark fable of Faust: the man who made a deal with the Devil. Throughout different retellings of the Faustian legend, the Devil or Demon that the title character makes a deal with has gone through a couple of different names. In the 1926 movie, directed by the king of Expressionist filmmaking himself, F.W. Murnau, the Devil is named Mephisto, and is played by Emil Jannings. In the movie, Mephisto places a bet with the Archangel Gabriel that, if he can corrupt a single righteous man and destroy all that is good in him by the time he dies, Mephisto will gain total control of the Earth, allowing him to plunge it into eternal darkness. To that end, Mephisto chooses for his target the good doctor, Faust, and makes a deal with him, acting as his servant at his beck and call, in exchange for his immortal soul. At first, Faust is happy to make the pact…but as time goes on, as you might expect, things don’t exactly go his way, and the tension rises as we wonder whether or not the trials and tribulations Faust goes through will either lead him deeper and deeper into the darkness, or allow him to ultimately see the light. Jannings’ performance as Mephisto is, admittedly, a bit overdone, even for the time period we’re talking about, but he’s not without his effective moments. I especially love the parts of the film where we see the Devil in his true form; they’re surprisingly powerful, even to this day.

7. Cardinal Richelieu, from The Three Musketeers (1921).

If Jannings’ Mephisto is a masterclass in over-the-top cape-swirling villainy, then Nigel De Brulier’s work as Cardinal Richelieu in the 1921 adaptation of “The Three Musketeers” is the opposite. This is a surprisingly subtle and restrained performance, especially for the time period. With many takes on Cardinal Richelieu, as he is portrayed in the Alexandre Dumas swashbuckling epic, it’s hard to imagine anybody believing Richelieu to be a good and fair person who would be able to command a country in the way he does. With Nigel De Brulier, he’s so tender, graceful, careful, and calm in his movements and actions, you don’t actually have a hard time buying: he NEVER gives away his villainy, except behind the king’s back. And even then, it’s never in the form of him twirling a moustache, or laughing, or smirking evilly; it’s always in his eyes. Something about his EYES changes, shifting with a dark, almost inhuman intensity that makes you shiver. He’s not necessarily scary, mind you, but there’s a decided sense of menace to him always lurking under the surface. He carries himself so elegantly and so gently, however, you’d never really imagine it. While there’s a grandness to the Cardinal, it’s never overstated, and it makes this one of the finer and more iconic takes on the character (if not the historical figure) ever put to celluloid.

6. Dr. Caligari & Cesare, from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

One of the earliest Expressionist movies ever made, and still regarded as one of the greatest. “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” focuses on a series of mysterious murders that occur in a fictional hamlet in Germany, which are revealed to be the work of a carnival magician, Dr. Caligari, and his somnambulist assistant, Cesare. Caligari, you see, is the director of a local insane asylum, and has apparently gone a bit bonkers himself; he uses Cesare to commit crimes for revenge, profit, and just about anything else under the Sun. Under Caligari’s hypnotic control, the somnambulist acts his human puppet, knifing and strangling anyone that Caligari commands him to kill. Their downfall comes when the pair attempt to abduct, rather than outright kill, a beautiful young girl. Caligari was played by actor Werner Krauss; Cesare, meanwhile, was played by Conrad Veidt – one of the most noted German actors of all time, and one of the most famous performers of the silent era. Cesare was essentially the role that made Veidt’s career. In contrast, it is effectively the height of Krauss’ career; while Krauss was highly recognized onstage, and did many more films following this one, he ultimately faded from public consciousness after his stellar performance as the mad showman in this picture.

5. Captain Hook, from Peter Pan (1924).

This silent version of the J.M. Barrie fantasy/swashbuckling classic was highly influential on the later Disney version, which is perhaps one of the main things that has prevented this picture from fading totally into obscurity. However, with that said, it is an excellent interpretation all in its own right, and deserves to be recognized for more than just the lingering thread connected between itself and the Great and Powerful Mouse. Peter’s arch-nemesis, the nefarious Captain James Hook, is played by Ernest Torrence in this outing. For the most part, Torrence plays Hook in a classic melodrama style, giving him many a foppish gesture and cackling (but silent) laugh. However, for all the comedy his Hook provides, the Captain is no pushover: for example, in his final duel with Peter, Hook proves to be a force to be reckoned with, and is surprisingly solemn and dignified in his defeat. On top of that, for all his hamminess, the Captain is a genuinely clever customer, always having some new scheme or trick up his ruffled sleeve. I really love the mixture of old-fashioned crook, sophisticated gentleman, and genuinely dangerous opponent that Torrence brings to his performance of the character. In my opinion, it’s one of the Top 10 best takes on Captain Hook ever done, and easily gets high marks on this list.

4. Rotwang, from Metropolis (1927).

While most villains of the 1920s era, as you’ve seen so far, were relatively straightforward antagonists, Rotwang is actually a bit more complex. True, Rudolf Klein-Rogge’s performance is still massively melodramatic – Rotwang is one of the most archetypal mad scientists of all time, known for his wild-eyed stare, fits of deranged laughter, and theatrical gestures. But the actual character is a surprisingly tragic villain: in this sci-fi epic of the silent age, Rotwang is a brilliant inventor and a member of the leading party in the government of the titular city. He is traumatized by the death of his long lost love: a woman who chose another man over Rotwang, and then died horribly giving birth to the man’s child. Rotwang thus begins to build a mechanical woman – a robot who will replace his beloved, and will allow him to get revenge on those who he believes should suffer for his many agonies. Over the course of the film, Rotwang’s obsession consumes him more and more, driving the unhinged scientist further and further into insanity, as he becomes increasingly delusional and twisted. Rotwang is a character torn between two worlds: he is neither of the elite upper class that rules the Metropolis, nor is he of the poor and oppressed who toil away to keep the city going. The tension of his status and the torture of his mental state make him a compelling villain indeed; we feel sorry for Rotwang just as much as we are entertained and at times creeped out by how looney he is. I had a hard time deciding where to place this maniac, and ultimately, he fell just short of making the top three…but hopefully, those I did choose for the Top 3 won’t disappoint.

3. Mr. Hyde, from Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde (1920).

Played by John Barrymore. Barrymore, of course, was one of the greatest actors of his day, known primarily for playing romantic cavaliers, dashing heroes, and sensual anti-heroes. I think this rap sheet is why I consider his work as Jekyll & Hyde to be my favorite of his performances, as it embodies just about everything Barrymore was, and what he was capable of doing. As Jekyll, Barrymore plays it mostly fairly subtle and straight. He’s handsome, gentle, but there’s always this slightly dangerous gleam in his eye. Jekyll in this film is depicted as a virtuous soul who becomes curious about the pleasures of evil, and you can see in him that hunger and lust in a repressed, careful state. As Hyde, Barrymore REALLY lets loose: the actor was known for being something of a ham, and as Hyde, he goes for broke. But, much like Mephisto and many other characters of this period, he can be surprisingly effective. Barrymore’s Hyde is actually quite scary in just how VICIOUS he is; he’s utterly manic and so deeply creepy in his appearance, gestures, and overall attitude. The movie likens Hyde to a spider (as opposed to an ape, which would be the most common animal motif in later times), and Barrymore plays with that intensely, as Hyde creeps and crawls his way through scenes, only to then pounce with incredible ferocity and intensity at the moment you least expect it. While certain moments are a bit much, for the most part, it’s a deeply troubling and menacing performance. Barrymore holds no punches; other villains and anti-heroes he played had some sort of sympathetic or seductive quality to them, but Hyde really doesn’t so much. He preys upon desperate people, and he lures them in not with seductive elements but with promises of fortune…all while still being a dominant, sensual creature in his own sick, twisted way. He’s utterly repellent, yet he’s such a joy to watch because Barrymore just throws EVERYTHING into it. It’s especially impressive that the transformation from Jekyll into Hyde works using relatively minimal makeup. In the earliest scenes, there’s no makeup at all, aside from the hands…but as the film goes on, and Hyde’s evil grows, he becomes increasingly hideous. Even then, however, Barrymore mostly just relies on his own bones and muscles to make the change happen. Very little is done to his FACE, or even to his body, it’s just John Barrymore making himself more crooked than Henry Brandon’s Barnaby! You get the feeling that, as Jekyll, Barrymore – like the character himself – is holding everything in, trying his hardest to keep himself restrained. So, when he gets to the transformation scenes, and to the scenes where Hyde gets to play in full force, he just launches into it with more fire and steam than anybody else. He, more than anything or anyone else, makes this my definitive take on the characters and the story, and definitely a shoe-in for the top three.

2. Count Orlok, from Nosferatu (1922).

I know that some people may be surprised I’m not calling him who he REALLY is – Count Dracula – but I think most people recognize that, while the story and character of Nosferatu are based on Bram Stoker’s Gothic classic, they’re also sort of in their own little world, in a bizarre way. When you think of Dracula, the name usually doesn’t conjure up images of Count Orlok; it usually makes you think of Christopher Lee, Bela Lugosi, or maybe Gary Oldman. (Or, if you’re an anime fan, Alucard.) And true, American releases of the film (which are gobshite) did give the characters their proper names, and equally true, the remake in the 70s – “Nosferatu the Vampyre” – did the same. However…ehhhhhh, screw it, I’m calling him Count Orlok. It just feels weird outright calling this one Dracula. ANYWAY! As the first (surviving) film interpretation of one of my favorite books and villains of all time, Orlok – as played by Max Schreck (please keep your Christopher Walken jokes to yourself) – definitely has a soft spot in my heart. There’s nothing suave or seductive about this take on the vampire king; the Count is depicted as a bat-or-rat-like creature who prowls and scurries through his scenes, spreading death like the Plague and causing havoc upon civilization simply to satiate his neverending thirst. Some versions of Dracula paint him to be a monster in human skin; others a human in a monster’s skin; this one basically strips humanity from the equation altogether. He is a monster, plain and simple. And to this day, he’s a powerful image of evil; there are still people who find this movie – if not outright SCARY – at least a little creepy here and there, and it’s largely due to the personification of Dracula/Orlok in the picture. The imagery of Orlok has proved to be indelible; true, Dracula himself has never really taken much in terms of his pop culture status from this movie, but the image of the vampire in “Nosferatu” has had influence. Some versions of Dracula have definitely taken influence from Orlok on occasion (such as the aforementioned remake), and even other, non-Dracula vampires have been touched by his raking claws. The vampire in “Salem’s Lot” is directly based on Orlok; the characters of Brauner and Olrox in the Castlevania franchise are both designed to resemble Orlok (in fact, the latter even has a name that sounds quite similar); The Master from “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” is yet another Orlok-based villain; these are just a few examples. This freaky fiend may not be the first thing you think of when one says “Dracula,” but he is most assuredly among the first things one thinks of whenever you say the word “vampire.” And as a huge fan of Dracula, this movie, and vampires in general, I have to give him credit where credit is due.

But as iconic as dear Count Not-Dracula may be, there is one silent film villain I like even more…

1. Erik, a.k.a. The Phantom, from The Phantom of the Opera (1925).

Played by the Man of a Thousand Faces himself, Lon Chaney. (You’ll find two more villains from his repertoire in the Honorable Mentions below.) Chaney, in my opinion, was the single greatest actor of the silent era. If the 1920s were the beginning of modern movies, then Chaney’s peformances in them were the beginning of “modern performances,” so to speak. Sure, they were theatrical, but the man could bring such emotive power to his work, without it ever feeling like it was too much, or making it to corny, that you never really minded. And he was highly versatile; not only were his personal skills with makeup and costuming incredible, but he could play with his body as much as his face. He could be a clown, a mobster, a gentleman, a thug…or, yes, a Phantom. Erik, in my opinion, was the pinnacle of what silent cinema was capable of doing with an antagonist: is he theatrical? Yes, he is, but that’s sort of the point of the character: a deranged opera buff, inventor, and generally multi-talented genius whose hideous face belies a soft and tragic heart. His pain and his misery feel startlingly real, and while he can be dangerous and scary, he’s still someone you feel sorry for. Really, if I have any complaint about this character, it’s the way he goes out, since I’ve never really liked the way the classic silent version ends…a lot of behind the scenes kerbobbling was the ultimate culprit there, though, so I can hardly blame the actor or even the character. It’s just part of who he is, and how his story ends, and you can read some interesting things into it. Whatever you think of the final result, there’s no denying that Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera is My Favorite 1920s Movie Villain. Case Closed.

Honorable Mentions…

Jack the Ripper, from Pandora’s Box (1929).

Played by Gustav Diessl. The Ripper, in this movie, is less of a straightforward antagonist and more of a particularly nasty “final boss” our less-than-pure heroine in this story must face. The infamous serial killer is displayed as a slightly tragic figure, too, as he is shown to be unable to entirely control his actions, which, to me, is always in equal parts sad and frightening. He’s not in the film for very long, but the sequence featuring this infamous figure in history is certainly memorable.

The Cat, from The Cat and the Canary (1927).

This classic murder mystery features a mysterious villain who is only ever seen in the form of a long, lean arm, which ends in a hairy, bony hand with enormous claws…ever ready to tear out the throats of his victims. A major part of the story is figuring out the identity of the unseen killer, who earns his name from the way he rips up his victims with said claws. It’s frequently spooky stuff to watch, even now!

Other Honorable Mentions Include…

Captain Ramon, from The Mark of Zorro (1920).

Fagin, from Oliver Twist (1922).

Alonzo the Armless, from The Unknown (1927).

Clan Dillon, from Nevada (1927).

1-3 go without saying

![The Three Stooges scared of... [Blank]](https://images-wixmp-ed30a86b8c4ca887773594c2.wixmp.com/f/c52cfd32-9473-4939-abb6-1aed39529c1f/dcoxeth-5b90ef7b-568e-4786-9418-e1ade90201eb.png/v1/crop/w_92,h_92,x_2,y_0,scl_0.092929292929293/the_three_stooges_scared_of_____blank__by_mrtoonlover83_dcoxeth-92s.png?token=eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJzdWIiOiJ1cm46YXBwOjdlMGQxODg5ODIyNjQzNzNhNWYwZDQxNWVhMGQyNmUwIiwiaXNzIjoidXJuOmFwcDo3ZTBkMTg4OTgyMjY0MzczYTVmMGQ0MTVlYTBkMjZlMCIsIm9iaiI6W1t7ImhlaWdodCI6Ijw9OTUxIiwicGF0aCI6IlwvZlwvYzUyY2ZkMzItOTQ3My00OTM5LWFiYjYtMWFlZDM5NTI5YzFmXC9kY294ZXRoLTViOTBlZjdiLTU2OGUtNDc4Ni05NDE4LWUxYWRlOTAyMDFlYi5wbmciLCJ3aWR0aCI6Ijw9MTAyNCJ9XV0sImF1ZCI6WyJ1cm46c2VydmljZTppbWFnZS5vcGVyYXRpb25zIl19.wLmZhWoZv-eNuW6r-VpYu9-ffykafehP9cjrvkyn914)