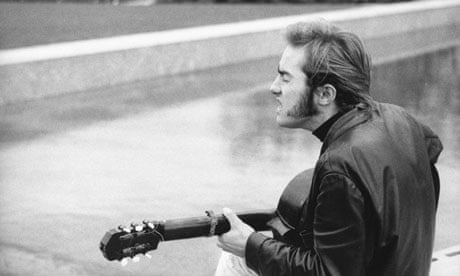

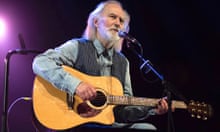

It's very simple being an acoustic musician. A few guitar cases and a roadie to set up the mikes. A rock band, now that's a different matter. Roy Harper has been expressing desires and fantasies for a band and electric music for several years now; with HQ (When an Old Cricketer Leaves the Crease in the US), his new album, reality emerges.

Reading on mobile? Click to view.

To get him used to the idea of travelling with an entourage, and also because he's quite popular there, and because the scenery is quite nice, Roy has just spent two weeks in Norway with a gaggle of roadies, media consultants and indeed, media. It was not a pleasant trip and could have been a forerunner of English audience reaction: the sight of Roy breaking out his Gibson for a quick blast of Highway Blues or The Game didn't go down too well with the indigenous folk fans, and this area, was soon toned down.

The country as a whole is quite straight, and the low profile madness of the Roy Harper entourage had hotels sending advance warning along the entire route, all because one of the media consultants got incredibly pissed, as is his wont, and staggered into manager Peter Jenner's room (scene of a quiet party) to pass out on the bed, the assembled thereby being inspired to drape his body and bed with towels, curtains, paintings, and any furniture not attached to the floor or walls. The hotel demanded 400 kroner for damages.

The promoters had applied to the government for a grant, since Roy was obviously a cultural asset. The government replied that a grant was forthcoming only if the cultural asset showed a loss. The promoters' booking saw to that. The peak was reached in what was supposed to be Stavanger – a reasonable sized town – but was instead the village of Vigrestad, 40km away. The last train to Stavanger left before Roy started playing, so they booked a motel and drove.

Having spent many wrong turns finding first the village and then the hall, Roy was presented with an audience of 200 in a hall for 2,000 assembled for an annual moonshine regalia celebrating their forebears' bootlegging during Norway's prohibition. He was inserted between two bop bands before an audience unwilling to appreciate the subtleties of an artiste; midway through a pleasant acoustic number, Roy got the roadie to assemble the amp and guitar behind him. Those who were there testify that the savaging The Game then received was aural vomit. Complete Harper overkill, as only he can. The audience was soon chanting, "Roy Harper, go home!"

The promoter ran up to Peter Jenner. "Can't you make him stop?"

"Well no, not really. He does get like this."

Meanwhile Beep Fallon, Media Consultant, had discovered Pete Rush, a mountain of roadie anyone would rue arguing with, backstage strangling a blueing Norwegian.

"Well, he was trying to set up mikes while Roy was playing. What would Roy think of me, man?"

Afterwards a very distressed promoter appeared. Roy's name had been misprinted on the tickets; he was ashamed. What, Ray Harper? Jay Harpic? Welcome ladies and gentlemen to Joe Harters.

Reading on mobile? Click to view.

BIRMINGHAM: No one is saying this is a band that will exist beyond one tour, but the rituals are the same. Why, it's the first days and already they're trading the names and numbers of their favourite dentists. There is a lot of residual tension from the past few weeks and the political manoeuvrings for a properly organised and presented tour. Norway is still in the air. Also, the printers have had a lot of trouble printing the album cover, though it is possibly Harper's simplest – it's certainly his most honest.

Until the cover is printed, the factory won't press the record, and the first copies are being transported to Birmingham's record emporiums only this day. Consequently, the public aren't familiar with the music. Although it's a logical conclusion for Harper, his idea of a rock band is not necessarily the thing people want to see.

Five minutes before curtain call, Clint MacDuff, Media Consultant, steps over a couple of twitching musicians in the dressing room and accosts Bruce Bruce, itinerant Oz ligger. "Hey, you're going to do the introduction." Bruce blanches. "No man. That moustache. You have to."

Bruce gave the ends of his musketeer moustache a twirl and acquiesced. Immediately, his lanky 6ft 3 body began an internal shake. He worked out an intro, bra sharped his Strine ["brushed up his Australian"], smoothed his rock star shirt and velvet jacket, donned his Peter Fonda shades, flicked his Peter Fonda feathers, slung a camera over his shoulders and ambled to the centre mike.

"Ladies and genrrulmen." (The voice boomed at him from the back wall.) "It is with grate pleasha and pride that I introduce to youse in their deybyew concert in the Western – or, indeed – any hemisphere. (The sniggers began to change to cheers.) A big round of applause please for ROY HARPER AND TRIGGER!" (Loud cheering.) He didn't stop shaking and his heart slowed down until midway through the second number. It was only then Bruce began to understand how a musician could feel nervous.

Referendum punches out, Roy's idea of "an intense rock song". The separation and sound is fantastic, and their confidence is great, Bruford pounding out a walloping offbeat, Spedding searing away by his side. Harper has absorbed well from his association with Zeppelin and the Floyd, Referendum stalks on a riff that will drive you crazy; Chuck Berry never envisaged a backbeat like this. Midway through the second break, Spedding already a showcase of precision and understatement, Bruford starts smiling.

The audience response is reassuringly positive – no Newport '65 here. Roy smiles and surveys the crowd for a minute. "I see a few faces – "He pulls a dazed stare and then laughs smugly. A guy at the back yells "Boogie!" Hallucinating Light is a rather laid back, echoed affair. The band takes its time, Spedding again proving the prime focus.

The Spirit Lives unveils almost every blues style in about four time changes. Interesting how Harper has written the obvious rock songs around ensemble playing, so that attention focuses on each instrument in different combinations rather than the rhythm being a vehicle to sustain the guitar. By the break it is quite clear that (a) Bill Bruford is an amazing drummer and (b) Chris Spedding is an equally amazing guitarist. Not a guitar hero, but always blasting forth with perfect understatement, thinking about solos in a crouch straight from Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran, bursting into a grin on a particularly satisfying explosion. Quite simply, you ain't seen nothing like it, and the sight is poetry.

Reading on mobile? Click to view.

"There comes a time in every rock star's life … " Harper thinks about the appellation and likes it. " … you have to pick up everything you can use and use it."

That sums it up, really. Roy Harper has evolved into a rock musician with such an explosion of confidence, the musicians to present him in the best light, and the songs to equal any rocker extant, that the acoustic music that Roy then wandered through was anti-climatic. Never did the reporter think he would encounter a situation where he was bored by songs of such magnitude as Twelve House Of Sunset and Me And My Woman, but the alternative the artist had revealed in the first 20 minutes was so stunning, so much more commanding, a man and his guitar couldn't help but suffer.

Significantly, throughout the acoustic section Roy's guitar and voice are being continually treated, approaching at times a mathematical precision in duplication of studio production. One line will be echoed, or a word, or the timbre will change. The guitar will build echoplex canyons, solo with its echo, roll over the play dead. Finally, the fumblings of the electric Highway Blues unveiled at the Albert Hall have reached fruition in a live equivalent of the omnipresent Spectorian over-dubbing of the albums. A pity it's overshadowed by Roy's flowering into a band.

Within its own tight, it was great. Twelve Hours Of Sunset and Commune worked their usual magic, and Me And My Woman was from another plane altogether. The echo giving his ragged voice a slightly superhuman quality, he sang as if possessed, haunted by the images of the lyrics, twisting words and phrasing. "I wanted to write a song that developed and I really got one there."

While a roadie changes guitars, he gives one of his now sharply curtailed raps. "A friend once said when he heard I'd written a song of such calibre, 'Christ, why did you have to write a song about cricket? Then he heard it and said, 'That's not about cricket, it's about life.'"

Well, When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease could probably be interpreted in a number of ways; its evocation of late afternoon, with the old master facing the final over of the day is more nostalgic than a Hovis ad, but its aching intensity and emotional imagery brings a lump to the throat every time. On record, with David Bedford's incredible brass arrangement so mellifluously recorded, it's enough to cause terminal depression.

It was only as he fought back the urge to write a suicide note while simultaneously transported by the deeply felt beauty of it all that the reporter finally realised Roy Harper's great originality. He treats his songwriting as artefact. A simple realisation perhaps, but with rock's throwaway ethic and treatment of lyrics as something to stick over the music, and Roy's penchant for intensely personal symbolism, the obvious can be obscured.

This is not to say Townshend, Jagger/Richard et al aren't serious and great songwriters, but Harper seems to treat his songs as pure object, outside the structures and limitations of any musical form or tradition; creations that will validate the author's worth and artistry long after his demise. (That he won't be famous until after his death is a Harper fixation.) That Roy is an original the reporter had decided since he first heard Stormcock without ever having heard of Roy Harper; the guitar style, the vocal philosophy, Roy's automatic belief that he is an artist (in the historical sense of the word) rather than an entertainer and the equally automatic application of that thinking to his work. But there was something else again, and as the imagery was consciously made more accessible, the glimmerings occurred. It reaches fruition with songs like Cricketer and The Game.

Apart from Cricketer, whose totality exists almost a priori, the best songs on HQ are the two all-out rockers: Referendum and The Game, where the musical content is finally angry and cutting enough to fully complement and support the anger and power of the lyrics. More important, if you don't listen to the lyrics they still make great dance tunes.

Reading on mobile? Click to view.

The Game is destined to be one of the great rock songs. Built on a skull-crushing riff not a million miles from You Really Got Me, it's impossible not to be floored by its power and majesty. The last number, the band are quite enjoying themselves by the time they power into it, stomping out like an enraged cyclops. Roy is chomping on the steamhammer rhythm, facing the audience as he bites out the lyrics. [Chris] Spedding is stuttering, throwing in stray licks around the edges, then falling back while Bruford makes melodic with the percussion, dropping in again with sounds straight from a Don Ho steel guitar. Dave Cochran, the diminutive bassist, continues to look vaguely bored as he fingers out earthquake riffs.

As Spedding bounds into a punishing solo, it becomes apparent that this song is going to grow into a monster. Harper turns to Bruford, who starts to punch more and more. Slowly a grin begins to spread across Roy's face and he starts bounding. The grin gets wider and wider, the feet start kicking and jumping; the band is born. They thunder into the final riff and the crowd goes berserk.

Of course, there had been the usual Harper walkouts early on, but the numbers were surprisingly small, and the reaction of those who stayed was resoundingly appreciative. For an encore the band rockabilly, through Grown Ups Are Just Silly Children, Roy doing a Daltrey with the mike, grinning the whole time.

After champers and back slaps and a Chris Spedding fan has produced both solo albums for autographing, the dissections begin. The band want to play longer, the acoustic section felt too long, certain structures need changing, the mixing and electronics need sharpening.

HEMEL HEMPSTEAD: The fourth gig. Harper now starts with an acoustic set, finally arriving at Hallucinating Light. As he moves deeper into the song, there is a sudden cymbal tinkle and the band stands arrayed behind him. Masterful.

Now that they have longer to hit their stride, the band sound like a diving Stuka: no nervous energy, just a dynamite band blowing the roof off. Bruford, Cochran and Harper are really churning those rhythms, Bill sometimes appearing as if in a trance. Meanwhile, Spedding stalks the edges, attacking, drawing back, dropping bombs here and there, making music that defies description. Harper is still drawing strength from Bruford, but he's also gotten into posing next to Spedding. He seems to be enjoying himself immensely.

Afterwards, Bill Bruford is engaged in conversation. A seemingly quiet individual who likes to turn up right before the band go on and doesn't like being introduced from the stage, between an endless variety of hilarious American spade routines he declaims to Harper's elfin lady.

"Drum solos are a joke. Anyone could do a drum solo. I could teach you a drum solo in two hours." Done!

Elsewhere, the artist and reporter are getting to grips over a cassette. After all, Ralph McTell doesn't rock, Clifford T. Ward certainly doesn't roll. So what's it about Mr Harper? Were you paying a lot of attention – I don't know if attention is the right word – were you "aware" of the things Zeppelin and the Who were doing – I mean, how did The Game come about?

"I asked one of those guys in one of those bands you mentioned, I said, 'I'll wait for you and I'll be there when you need me, or you think you can ever use me in any way, or if your scene breaks up', and I waited for five years during which time I began to notice a lot of bands starting to reproduce onstage what I'd been doing on record. The only thing missing was the very basic ingredient of the lyrical content and also the depth of material, and here I was waiting in the shadows for somebody who was never going to come, but who was using me nonetheless."

What kind of things being copied?

"I should think Roger Waters plays Valentine three times a week, and as a friend said, 'I was talking to a American record man who said the first time he heard War Child that it sounded like Roy Harper, that English folk guy.' And he had no need to say that, because he didn't know that the guy was a friend of mine. I could go on naming names all night. I've recently become aware of the fact that I'm one of the sources, and there are very few sources, and to actively go around bragging that is like an advert for 'let's leave him out then'.

"You can write yourself off doing that one … If you're going to print this you'd better print the lot; it could look very funny edited. Because these are friends of mine who nonetheless have been influenced by me, and it's much more than their influence on me, musically speaking. Robert Plant's influence on me as a person is another thing altogether."

Is the realisation of the band how you envisaged it?

"Yes. The components aren't as I imagined them. For instance, when I first met Bill I thought he was far too controlled for a drummer. Because what I know of drummers as a race, they're crazy. But now I begin to see where young William's craziness is, we're possibly a bit edgy with each other at the moment, because I'm not saying much. I've reached a silent period in my life, because the world's turning at a fast pace and I'm taking a lot in from outside the band and outside my immediate surroundings, which is important because it's likely at a later date to deluge out into song.

Reading on mobile? Click to view.

"I'm at a period when I'm wondering, and everything I see is changing me and everything I see is changing the world too. So I'm not very communicative with my immediate fellows, but there will be a time, if the band lasts that long, where I will be much more so, and will have to be.

"So far, I think I've done the most sensible thing, which is go for the best musicians rather than fellow occupiers of the same … I was going to say mental ecstasy, but it isn't so ecstatic at times. Because they, more often than not, are fellows who think your last sentence is the bees' knees. I went obviously for the best musicians available and for the ones that I'd received good feelings from, namely Spedding, because having vaguely known him for years he became an appealing figure in the same sort of way that Page is."

As for the quality of the songs … "I understand the rock media. I understand where life has got itself to in terms of music. There is a point where a generation gap is formed, and I think there is one between my own type of music and my own type of thought wave, and the best one that will come out of the Bay City Roller era.

"When you hear these kids go, 'Rollers Rollers Rollers', and somebody else says, 'The Beatles', and somebody else says, 'Who are they?', you realise you're the same age as the Beatles and that you belong to a different pattern of circumstances, because the pattern of circumstances that took over in the late 50s and 60s was one of euphoria, which has been taken over now by one of industrial dispute, simmering world peace that's kind of an edgy existence, so music in its basic banal form is going to mirror that kind of situation instead of Strawberry Fields.

"I feel that a generation gap has already grown between the two that I'm trying to bridge, and in this time of silence I'm trying to figure out where I am with regard to where I've been, and where I should go to be able to relate to the maximum amount of people without regard of age."

© Jonh Ingham, 1975

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion