The opening scenes of A Matter of Life and Death are among the most audacious and moving ever confected by the cinematic magicians Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. After the whump of arrow on target that announces a production by the Archers, we are pitched into the blue-black vasts of space – the film-makers had consulted Arthur C Clarke about the design of their cosmos – where a voiceover guides us past eerie nebulae and exploding stars to our own fretful corner of the universe. On Earth it’s the night of 2 May 1945, a thousand-bomber raid has left a German city in flames, and British pilots have turned for home. Fog rolls across the screen, radios crackle with the voices of Hitler and Churchill. “Listen,” says the narrator, echoing a line of Caliban’s in The Tempest, “listen to all the noises in the air.”

Cut to a red-lit control room, a sinister nest of Anglepoise lamps, and in their midst a young American radio operator named June (played by Kim Hunter) who is trying to speak to the pilot of a damaged Lancaster as it limps across the Channel. The bomber is on fire, its fuselage gaping, ruined instruments rattling around behind Peter Carter (David Niven) as he recites into the ether lines of poetry by Raleigh and Marvell. His crew have all bailed out or been killed; the plane’s undercarriage is gone, and with it any hope of landing safely. Will he jump too? Yes, he tells June; but there’s a catch: “I’ve got no parachute.” The exchange that follows between the Boston-born WAAF and the doomed English airman is absurdly (and knowingly) exalted: “You’re life, June, and I’m leaving you!” On the film’s release 70 years ago, some critics balked at the cardboard romanticism of the scene. But I’d challenge anyone to stay untouched to its end, watching Peter steady himself for a chuteless fall into the fog.

Miraculously, the young pilot survives, and is washed up on a beach in Devon, where he meets June cycling across the sands. But Peter was meant to die, and the authorities in the next world will not let him go, just because he has fallen in love. So far everything has been in ravishing colour, but suddenly we are in a black-and-white modernist heaven where the first bureaucratic mistake in centuries has set off celestial alarm bells. A heavenly “conductor” – Marius Goring as a French aristo fop – is dispatched to retrieve the undead man, but Peter resists, and a trial looms at which he must plead for more time on earth. A Matter of Life and Death is a self-consciously Shakespearean comedy of sorts, and a lurid experiment in cinematic colour and scenography. But it’s also an end-of-war reflection on the living and the dead, including those who have been missing for a time, stranded in between.

The film began as an expressly propagandist project. Jack Beddington, head of film at the Ministry of Information, asked Powell and Pressburger over lunch: “Can’t you two fellows think up a good idea to improve Anglo-American relations?” By the time they made “AMOLAD” (as all involved called it), the Kentish director and Hungarian screenwriter had twice exceeded their war-effort brief, with controversial results. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp – whose star Roger Livesey returned in A Matter of Life and Death as the neurologist Frank Reeves – scandalised Churchill with its portrait of a good German and its mockery of a certain English bluster. And in A Canterbury Tale, Powell and Pressburger revelled in a twisted vision of old England at the near-gothic (but again comical) expense of the film’s message about Anglo-American cooperation before D-day.

There were other origins and influences at work. In 1944 the German press reported that a British rear gunner had fallen 18,000ft into a snow drift and survived. Three years earlier, the Times had published posthumously “An Airman’s Letter to his Mother”: a young man’s fearless and somewhat pompous missive about his willingness to die in battle. Powell made a short film around the text (which was read by John Gielgud) but though he greatly admired the core message of the letter, he removed a passage about the war being “a very good thing”, and another about the British empire, “where there is a measure of peace, justice and freedom for all”. At the end of the war, troubled by spectres from beyond, the airman of A Matter of Life and Death fears he may be “cracked”. But he has no historical delusions; one of the first things he tells June, from his burning cockpit, is that he is “Conservative by instinct, Labour by experience”.

Pressburger had delivered to Powell a more obviously ghostly script, complete with transparent emissaries from the other side, from which the director tried to excise as many conventional signs of the supernatural as possible: there’s only one instance, for example, of anybody walking through walls. (This is not Blithe Spirit, even if both films turn at the end on similar high-speed road accidents.) Powell was determined that both Earth and heaven – it’s only called that indirectly, in a fleeting cameo by Richard Attenborough – would be solid and consistent, though each is exotic in its way. And though the neurological explanations for Peter’s visitations from the afterlife can seem hokey – “You mean ... insanity?” asks a colleague of Reeves’ portentously – Powell did his best to base the visions and other symptoms on recent medical literature.

The plot takes the risk of combining time travel, psychiatric melodrama and divine or supernatural intervention on Earth: all of which themes had recently been explored in other movies, though not yet in the same heady mix. The film recalls aspects of Hitchcock’s Spellbound from the previous year, Ernst Lubitsch’s Heaven Can Wait (1943) and most obviously Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, which was released around the same time as the Archers’ film. Pressburger had already conjured a prototype heaven in his screenplay for Max Ophüls’s first film, I’d Rather Have Cod Liver Oil. There are reminders also of William Cameron Menzies’ Things to Come, from a decade before: the Archers’ sci-fi heaven is all gleaming white with transparent plastic furniture, and the newly arrived dead receive their angelic wings in cellophane dry-cleaning bags.

But the most seductive element in the film’s magical relay between heaven and Earth is its treatment of colour. Filming was delayed for months due to shortage of colour film stock and cameras. The Archers’ established wartime cinematographer Erwin Hillier refused to share a credit with Jack Cardiff, the young Technicolor technician Powell hired for the colour sequences, and so the whole movie was given to Cardiff. He had assumed that Earth would be in black and white, the other world in colour – The Wizard of Oz supplying the model. But Powell and Pressburger wanted the reverse. Their real world is made of golden light, pink roses, blue skies and June’s scarlet lipstick. Heaven is all sparse and pearly monochrome, shot by Cardiff on colour stock without the usual dyes, so that seamless dissolves could be effected between worlds. Its melodramatic opening apart, the film’s most celebrated moment comes when Conductor 71 first appears on Earth, among big blushing rhododendrons, and quips: “One is starved for Technicolor up there.”

A Matter of Life and Death was shot on Stage 4 at Denham Studios, where Powell and Pressburger had lately mocked up, with painted flats and blown-up photographs, the interior of Canterbury cathedral for the closing scenes of A Canterbury Tale. Their production designer Alfred Junge was responsible for some of the most dazzling images in the Archers’ work, and this film is replete with exquisite visual inventions. At times these are subtle and sly: the fiery Lancaster that allowed Cardiff to give Niven’s face a sunset glow as he contemplates his end; the heavenly clock that becomes a halo around the head of Kathleen Byron’s empyrean administrator. Junge’s most prodigious contrivance was the 20ft-wide, 106-step, near-silent escalator (nicknamed “Ethel” on set) that connected heaven and earth, and gave the film its slightly cowardly US title: Stairway to Heaven.

The staircase, with its direct allusion to the motif of Jacob’s ladder in the Bible and The Pilgrim’s Progress, is one of the film’s many literary references. (John Bunyan himself puts in an appearance when Dr Reeves arrives in heaven to defend Peter.) Peter Carter is a poet, and Reeves sees the world like a poet, at least according to June. Reeves, the bearded magus, is the most obvious link to The Tempest. Like Prospero, he is a sort of director, preparing the stage for magical or miraculous events, in the end abjuring his own specialist knowledge so that the lovers may thrive in the last scene. When Reeves first meets Peter, it’s in a stately home requisitioned by the US Army, and the troops are rehearsing a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream – many key moments in the film unfold in something like Shakespeare’s magical green world, with the principals framed or shadowed by flowers or ferns.

In other worlds, A Matter of Life and Death is blatantly theatrical in places, and prepares the way for the Archers’ more stagey later productions, such as The Red Shoes and Oh ... Rosalinda!! But it is also all about film, its art and artifice. Peter is said to be suffering from “a series of highly organised hallucinations, comparable to an experience of actual life”. It sounds like a definition of cinema. When June calls Reeves a poet, it is because she visits him in a camera obscura at the top of his house, from which – a bravura bit of special-effects work – he observes on a concave screen all movement in the village below. And in the film’s most obvious play with the wizardry of cinema, Conductor 71 is able to halt time and speak to Peter alone, turning the action around them into a frozen frame or still.

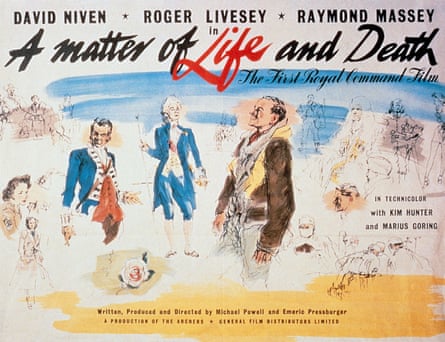

On Friday 1 November 1946, thousands of Londoners crowded into Leicester Square to watch the King and Queen attend the premiere of A Matter of Life and Death, which was also the first Royal Command Film Performance. Critical response was mixed. In the Observer, CA Lejeune complained that the film “leaves us in great doubts whether it is intended to be serious or gay”. Others objected, yet again, to a perceived anti-British strain. In France, the great film theorist André Bazin reviewed the film, commended its humour and dismissed its design as so much regrettable “plaster and Plexiglas”. Bazin had missed, behind the metaphysical wit and baroque surface, the true strangeness of Powell and Pressburger’s masterpiece, which is after all a version of the Orpheus myth. Four years later, in Orphée, Jean Cocteau would film that tale with radio broadcasts, an undead protagonist and otherworldly tribunal – but the Archers were there first, expressing with amazing lightness of touch a real yearning to bring the war’s dead back to life.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion