The term “film composer” might be useful when referring to the work and career of John Williams. But, in his case, it would be also extremely reductive. While it’s true that the Maestro dedicated much of his artistic life to work for the Hollywood film industry, he has always showed a great deal of versatility, typical of musicians who don’t limit themselves just to one single area. Pianist, jazzman, arranger and, in the end, composer of works for films and the concert stage, Williams diversified his artistic output since the early days of his professional career, exploring different sides of his musical personality. Looking at him this way, it can be said without being proven wrong that he perfectly embodies the creative breadth of the 20th century composer and musician.

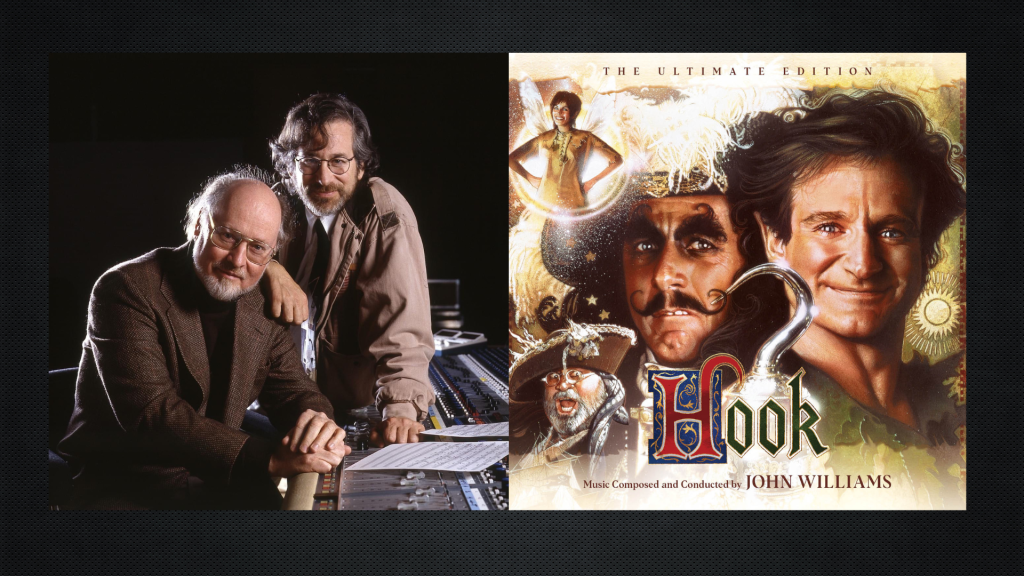

Given his classical studies and background, it was a natural consequence for John Williams to pursue chances and opportunities to write music for the concert hall. This fascinating journey began during his early years as a composition and piano student, when he wrote sketches for a piano sonata in 1951 and, a few years later, a quintet for winds. Both works were never performed and the composer only briefly talked about them publicly, but it’s safe to assume they were pieces that a very young John Williams used mostly as a training ground, to stretch his own musical muscles and try solutions and ideas. After his studies at Juilliard in the mid-1950s, Williams returned to Los Angeles and started to work as pianist in film studios. The many possibilities offered by the Hollywood film industry helped young Williams to climb the ladder from the piano bench to the podium. Alongside film studios, John Williams worked extensively in the booming record industry, showing a great deal of versatility and dexterity both as pianist and as arranger/orchestrator/conductor for singers and jazz bands. In this period, he bonded closely to his friend André Previn, who in the mid-to-late 1950s became a household name thanks to his exceptional work in the great MGM musicals such as Gigi, Porgy and Bess and It’s Always Fair Weather, but also on the jazz scene, playing on records alongside high-caliber musicians of West Coast jazz such as Shorty Rogers, Shelly Manne, and Russ Freeman among others. Previn and Williams shared a similar background (they studied with the same composition teacher, Italian emigré composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco), but more importantly, they shared a kindred spirit in both musical and personal terms, further nourished by the collaboration on several recording projects. Previn championed the music of his friend since Williams’s early days as a composer in Hollywood, as heard in this performance of a tune from one of Williams’s very first feature assignments, Bachelor’s Flat (1961).

The two musicians cemented their friendship even more so in the subsequent years, and as we’ll see, the relationship would become one of the essential factors for Williams’ own path to the concert stage as a composer of classical music.

In the early 1960s, John Williams started to get assignments as composer for feature films, mostly comedies and mid-to-low profile dramas. Despite the collapse of the studio system of the heydays of Hollywood, it was a time where composers were in high demand from both film and television companies, and some majors like Universal Pictures and 20th Century Fox kept their musical departments running, though composers were now contracted for single projects as freelance instead of being on the studio’s payroll. Williams was very active also as a composer for television shows, mostly anthology series like Alcoa Premiere, Kraft Suspense Theater and Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theater, and prime-time dramas such as Wagon Train and Checkmate. The composer himself later admitted it was mostly work-for-hire, but a very useful learning ground:

“The shows I was assigned to were the hardest shows, the hour shows, which meant I had to write about twenty to twenty-five minutes of music a week, score it, and record it. It was a tremendous learning opportunity for me. What I wrote may not have been good – it probably wasn’t. The main idea was to get it done, and I got it done.” [1]

It was perhaps in a moment of personal discomfort that Williams expressed his own frustration to his fellow composer and early mentor Bernard Herrmann:

“In the early sixties, I wanted to write a symphony. One day at lunch I complained to Benny about wanting to write some music other than film music. His answered, “Who’s STOPPING ya?” His answer was so blatant and direct—and right—that I went home and spent the requisite four or five months writing this piece.” [2]

Williams started to write the symphony in 1966, but the year before he composed a couple of other works for concert hall that are worth mentioning. Both pieces contributed in shaping Williams’s concurrent career in the concert hall and in finding his own personal voice.

In 1965, Williams accepted a commission from great jazz musician Stan Kenton to write a piece for his own Los Angeles Neophonic Orchestra, a newly-formed wind and percussion resident orchestra which had the mission to perform and record “New Music”, also called “Third Stream”. Kenton invited many young jazz and contemporary composers from the Los Angeles area to write pieces for his ensemble, including Marty Paich, Bill Russo, Elmer Bernstein, Lyn Murray, among others. Williams wrote a piece titled Prelude and Fugue, a brilliant 10-minute composition where he showed his love for 1930s jazz (the piece is dedicated to pianist Claude Thornhill, one of Williams’s inspirations as a youngster) coupled with the lexicon of contemporary orchestral music. The piece was premiered in March 29, 1965, at The Music Center in Los Angeles, as part of a concert also featuring legendary singer Mel Tormé.

Prelude and Fugue was then recorded by Kenton and his ensemble for their first showcase album released the same year, featuring pieces by Hugo Montenegro, Russell Garcia, Allyn Ferguson and Jim Knight. “The variety of ideas subtly but precisely woven through the score perfectly complements Williams’ geometric, lithurgical-in-mood constructions,” said the liner notes on the album, calling it also “an outstanding example of awesome beauty and incredible power.” [3] The piece features an impressive alto saxophone solo, performed by legendary sax player Bud Shank, perhaps anticipating by 40-something years some of the bebop-influenced alto saxophone writing of Catch Me If You Can (2002).

And the same year, Williams writes another piece for the concert stage, titled Essay for Strings. The composer picks a typical classical structure (the Essay is also commonly known with the French term étude) and propels his own personality into it, exploring and stretching musical ideas and materials to their apparent limit. In this case, it’s the sound of the string orchestra and its thick, imposing harmonic textures. Shades of Arnold Schoenberg’s seminal Verklärte Nacht (‘Transfigured Night’) can be found in some of the DNA of Williams’s piece, but perhaps for the first time in his career, the composer shows his more personal and intimate voice in a work of absolutmusik. The composer describes the work as “essentially dramatic” and it’s one of the very first examples of John Williams’s imagination going completely free in its own terms. André Previn immediately took notice and he was the first to champion the piece—he conducted the world premiere of Williams’s Essay on December 6 and 7, 1965 with the Houston Symphony Orchestra in a subscription program that also included a piece by American composer Ned Rorem, Maurice Ravel’s La Valse and Brahms’s Symphony No.2. The piece was given its West Coast premiere on May 24, 1967 at the University of Southern California, as part of a Rockefeller Grant-sponsored concert of modern music; the program was then repeated at UCLA and Cal State Long Beach.

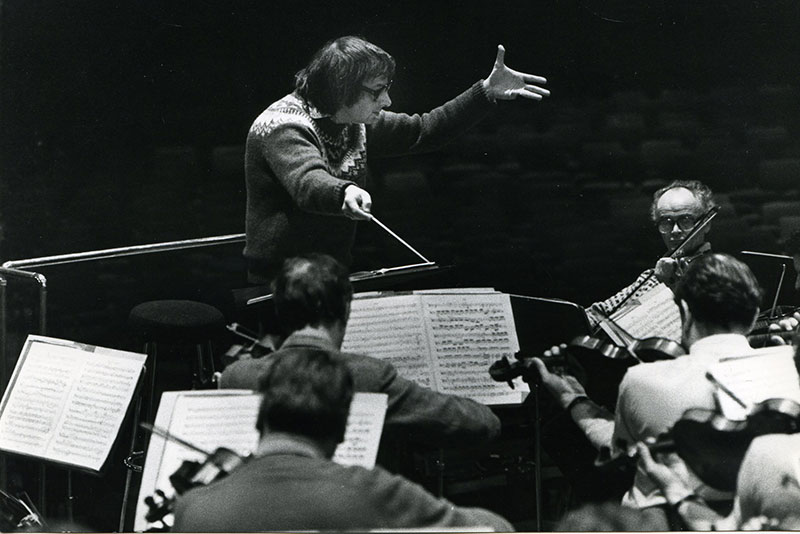

André Previn’s friendship and support (together with Bernard Herrmann’s urge) were essential factors for Williams’ subsequent work for the concert stage, the ‘Symphony No.1’. Williams completed the piece in December 1966 after working on it most of the year between several film and television projects, including the hit comedy How To Steal a Million. In 1967, André Previn was appointed music director of the Houston Symphony Orchestra, following the esteemed British maestro Sir John Barbirolli on the podium. The choice left many people surprised and almost puzzled—Previn was basically saying goodbye to his enormously successful career in Hollywood to pursue a new path in classical music. In this role, Previn didn’t want just to establish himself as an interpreter of standard repertoire, but saw it as an opportunity to present new symphonic works by living composers. His longtime friend John Williams fitted the bill perfectly, so he was more than happy to conduct the world premiere of Williams’s first major extensive symphonic work for the concert hall—Previn has always been one of the greatest supporters of John Williams’s concert music.

Dedicated to André Previn, John Williams’s Symphony No.1 premiered on October 21 and 22, 1968 in Houston, Texas, with the Houston Symphony Orchestra conducted by André Previn as part of the regular subscription series of the orchestra. In the same program, three major symphonic works were also performed—Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Serenata Notturna, four songs from Gustav Mahler’s Die Knaben Wunderhorn and Samuel Barber’s Knoxville, Summer 1915.

The whole second half of the program was dedicated to the world premiere of Symphony No.1 by John T. Williams—in the early 1970s, the composer used his middle name’s initial on several occasions to avoid confusion with the classical guitarist of the same name, who was already worldwide famous.

The concert program book describes the piece and its musical specifics:

It is in three movements and is cyclic in the sense that the principal motive of the first movement recurs in the succeeding movements in altered forms. The work calls for a fairly large orchestra with an ample percussion battery.

The cyclic motif opens the work, presented first in the woodwinds. It is a four-note turning figure and, although it goes through a variety of alterations in its return in the symphony, it has a very distinctive character that makes it easy to recognize. The first movement has three themes, of which the first and third are the most important. Even here, the third theme has a resemblance to the cyclic motive. The movement has a developmental character as each theme is presented in turn, immediately developed, and—after the first—combined with the opening motive.

The second movement begins with its own themes, the first presented by an unusual combination of bells, piano, vibraphone, harp, and triangle. This group also closes the movement, but here they play the second theme. The cyclic motive appears in the middle of the movement, introduced by muted trumpets.

After the maestoso introduction, the third movement turns to its principal allegro tempo, and the timpani states the cyclic motive in inversion. The clarinet then presents an altered version of this theme, which is imitated by the oboe and then the flute. This becomes the main material for this movement and serves to close it, after a climactic section.

While Williams employs chromaticism and dissonance freely in this work, the symphony does not appear to employ serial or other devices of the current avant garde. It is strongly rhythmic and its themes are distinctive. [4]

The notes describes an ambitious work, at least in terms of scope and structure, and it sounds interesting also in terms of what Williams was doing in his work for films around the same period—the composer was busy on several projects, among them a major adaptation and orchestration work for a new film musical based on Goodbye, Mr. Chips, starring Petula Clark and Peter O’Toole under the direction of Herbert Ross, with songs written by Leslie Bricusse. Williams was entering a phase of his career where he started to explore more varied and ambitious orchestral writing, and the Symphony was a natural consequence of his musical growth.

The composer attended the performance of the world premiere of his Symphony, just a few days before flying to London to oversee pre-records for Goodbye, Mr. Chips. There are no recollections or reviews of the performance available, but it’s likely major local newspapers covered it. Nonetheless, Williams felt that the work was already in need of improvements and reconsiderations, starting to show an attitude that would become one of his characteristic traits—the composer would frequently revise his works for the concert hall in subsequent years—and eventually planned to rework the Symphony, but that wouldn’t have happened until 1972.

During the late ’60s, film and television commitments were piling up, but Williams still tried to find time for concert music, mostly for his own pleasure:

“During that period, I was composing mostly for television and film. Whenever I had four or six weeks free, I still felt compelled to write music.” [5]

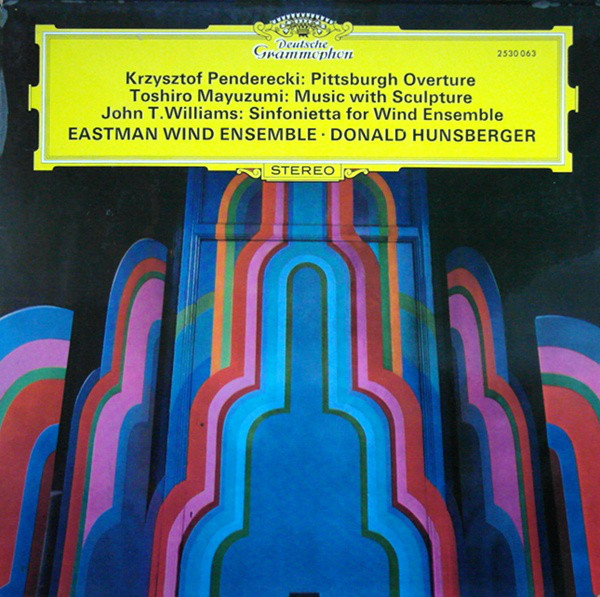

In 1968, the composer wrote a piece for winds and percussion on suggestion by MCA Music Publishing as a spotlight for the burgeouning world of concert bands. Titled Sinfonietta for Wind Ensemble, the composition was immediately picked up by conductor Donald Hunsberger, the music director of the esteemed Eastman Wind Ensemble, a concert band formed by students and undergraduate of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY. The Ensemble, founded in the early 1950s by Frederick Fennell, was key in popularizing wind band music across the United States and, during the 1960s, Hunsberger commissioned new compositions to create a new repertoire and put a spotlight on the Ensemble. Williams’s Sinfonietta is a unique work where the composer explored the specific textures and sonorities of the winds and percussion ensemble, combining modernism with allusions to jazz. Scored for a large expanded orchestra wind section, the piece is described by Hunsberger as “characterized by striking vertical sonorites and long melodic lines, which in turn are contrasted by slight jazz inflections. Williams utilized tight fugal writing creating tension and release through his apt use of the instruments of each family.” [6] The work is also a reminder of the composer’s affinity toward concert band music, a long-lasting love since his youth.

The work was recorded by Hunsberger and the Eastman Wind Ensemble, together with works written for the Ensemble by modernist composers Toshiro Mayzumi and Krzystof Penderecki, for an album released in 1969 by prestigious classical label Deutsche Grammophon.

Williams managed to continue writing concert music between film commitments—between 1969 and 1970, he completed a Concerto for Flute after being inspired by demonstrations of the shakuhachi, the traditional Japanese bamboo flute. It would have been the first of many concertos for soloist and orchestra in his career, a compositional form for which he always showed a particular affinity over the years. The Concerto would have seen its premiere only in 1973 in Los Angeles, with flutist Sheridon Stokes as the featured soloist and the UCLA Orchestra conducted by Mehli Mehta, as part of the popular Monday Evening Concert series. The Concerto was performed again on the concert stage a decade later though—the piece was performed again in Pittsburgh on May 7, 1981, with André Previn conducting the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra featuring PSO’s Principal Flute Bernard Goldberg.

After the success of the Sinfonietta, the Eastman School of Music asked the composer to write a new piece, on the occasion of their 50th anniversary in 1972. The composition, titled A Nostalgic Jazz Odyssey, was premiered again by Donald Hunsberger with the Eastman Wind Ensemble and it’s another exploration of contemporary dissonances combined with traditional sounding jazz-styled music. The callbacks to jazz vernacular create the effect of a water-coloured memory of a bygone era, not unlike Williams would do forty years later when writing the piano solo suite Conversations.

In 1968, Previn was appointed Principal Conductor of the prestigious London Symphony Orchestra, a post he would successfully held until 1979. Leading one of the world’s most distinguished musical institutions was certainly surprising for many people who tought Previn was still someone famous principally for his work for Hollywood and jazz, but the LSO entered a new successful era under his tenure. Other than performing for large audiences in concert hall, the orchestra started to appear frequently on television for the program Andre Previn’s Music Night, a show that turned the conductor into a star and made the orchestra a household name among classical music buffs. As he did in Houston, Previn introduced the audience to creative programming, shedding new light on classic British oeuvre, but at the same time presenting new music by contemporary composers. Some of the recordings made by Previn with the LSO in those years still remain a highly regarded reference for the repertoire.

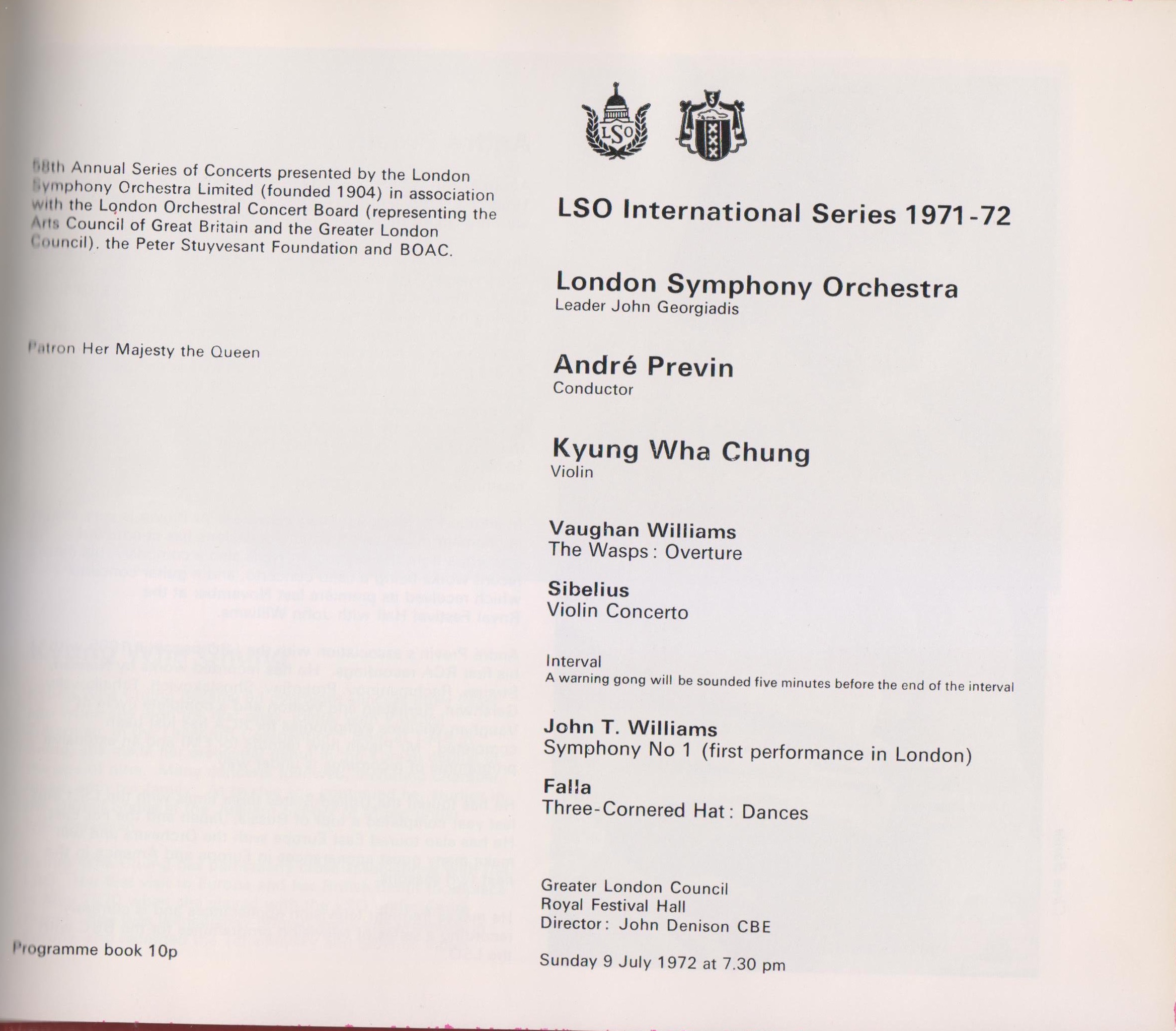

It was during the 1972-73 season that Previn presented again John Williams’s Symphony No.1 that he conducted four years earlier in Houston. The connection between Previn and the LSO was probably an enticing offer for the composer, who was already quite accustomed to the London music scene in those years, so Williams decided to extensively revise several passages of the symphony, particularly the second movement, for this European premiere. The work was scheduled to be performed on two nights at two different locations: the first at the opening night of the Nottingham Festival on July 8, 1972; the second in London at the Royal Festival Hall on July 9, 1972. On both nights, Williams’s Symphony was presented in a program featuring other significant works from three 20th century composers: The Wasps Overture by Ralph Vaughan Williams, the Violin Concerto by Jean Sibelius and the dance suite from the ballet The Three-Cornered Hat by Manuel De Falla.

The concert program notes contained a small biography of the composer and about the work wrote:

As in the Essay for Strings, there is a strong element of chromaticism, which influences both the texture and the character of the symphony. The work is scored for conventional large orchestra, including four percussion players, as well as harp, celeste, and piano. [7]

For this occasion, Williams himself provided a new short introductory note for the work:

“Since science fails to provide all of modern life’s solutions, I prefer, like Robert Graves, to believe in myths…at least where music is concerned. My music contains no truisms of musical relationship nor other scientific “conceit”.

My first symphony was composed in 1966, partly because of a life long affection for the orchestra as a medium of expression and partly because of my admiration for the vital and energetic qualities of my friend, André Previn.

The first of the work’s three movements is worked out on two basic themes, in simple metres of four, respectively. The second movement has jazz as its inspiration and features a flute solo written somewhat in the style of the late Eric Dolphy. The third movement features a fugato based on intervallic material taken from the first movement and proceeds through a parody waltz to the work’s conclusion.” [8]

Williams mentions British writer, poet and mythologist Robert Graves, who would become a source of inspiration for at least a couple of his subsequent works—Williams extrapolated text from “The Battle of the Trees”, one of Graves’s poems found in his book The White Goddess, as the basis for the choral piece “Duel of the Fates” featured in the score of Star Wars – Episode I: The Phantom Menace; and the same poem served as inspiration for one of the movements of his Concerto for Horn and Orchestra from 2003. Also interesting is the mention of African-American jazz musician Eric Dolphy as one of the inspirations of the second movement—Dolphy was an amazing multi-instrumentalist famous for his incredible improvisational qualities and his techniques in producing unique sounds; his style was frequently labeled as free jazz, but he was also influenced by bebop and contemporary orchestral repertoire by Bartók and Stravinsky. This reinforces the deep affection Williams always had with jazz and how it continued to inspire him in his music for the concert stage.

The composer was in attendance for the London performance and a few years later recalled the experience, and one unexpected guest among the audience, the friend and composer who originally urged him to write the piece, Bernard Herrmann:

“About ten years after the writing of my symphony, in 1972, André Previn performed the work at the Royal Festival Hall with the LSO. Benny said he wasn’t coming because he didn’t like Previn. […] André and I were running around the front of the box office side of the Festival Hall—and as we were fussing around, we turned to see Benny slinking into the hall, not wanting to be seen by us! He rang me up the next morning … and said, “It’s a good piece. I like the first movement, you have a good tune in there. What did ya cover it up with all those effects, all that excessive orchestration?” He was critical, yet supportive.” [9]

Herrmann wasn’t the only one with a hard judgement. The music critic of the London Times, Stanley Sadie, wrote a particularly harsh review of Williams’s symphony:

John T. Williams’s Symphony No. 1 […] shows a masterly grasp of two essentials: he uses the orchestra vividly and effectively, and can control tensions and architect climaxes…And yet—I hope I am not prejudiced by knowledge of his film background—there seems to be a lack of discrimination in his music, a lack of consistency, basically a lack of discipline that at abstract, symphonic composer must posess. The material is excessively diverse: a post-Webernish beginning, then a sentimental trumpet tune, next, an idea built on shifting chromatic chords—how do these ideas relate in a functional, dialectical way basic to symphonic growth? They do not: each is developed, and each recurs, to form a symmetrical shape, but not a whole. The Andante starts off with a fashionable glitter of vibraphone, glockenspiel and the like, and moves on to an impovisatory flute theme over ostinato blues chords; then comes a well architected climax, as if to form a ‘contrasting middle section’, there is an ingeniously orchestrated, but ingenuously conceived, recapitulation with high violins and horns playing to jazz chords while trumpets and trombones take over the flute idea. The finale is built round a fugue, which works up spaciously to a big tutti; but the pace is unsurely judged, the climax an event without a musically motivated cause. [10]

A less negative article by the Guardian’s music critic Gerald Larner reviewing the performance at the Nottingham Festival said:

Nottingham enjoyed the opening concert of its Festival […] They were enthusiastic, too, about the new work in the programme, John T. Williams’s First Symphony […] Actually it is only a fairly new work: it was performed in Houston six years ago. Since then, it has been revised mainly in the second movement, which is now one of the more successful attempts to combine jazz with the symphony. The American composer, known mainly for his film scores, was also a jazz musician at the time. Asked if Peter Lloyd’s performance of the big flute solo (written in the style of Eric Dolphy) had been idiomatic, he said “It was pretty close for a straight flautist.” To a straight listener, it sounded extraordinarily difficult, but interesting and set in a richly coloured context of pitched percussion. The outer movements are also resourcefully scored, particularly for brass, but less convincing in other aspects. It is not the melodic material, functional if unremarkable, which causes doubts. It is more to do with construction of these two movements and the way they leap into climaxes which are so little motivated and so little prepared that the listener has no opportunity to become involved. [11]

It’s unknown if the critical panning, and Herrmann’s judgement influenced the composer’s own assessment of the work, but in 1978, he admitted to journalist Derek Elley some of his own concerns, and the intention to revise it once more:

“I want to re-work the Symphony some time: I like the first movement but there are some glaring flaws in the second movement and the last part of the finale which I think I can now put right.” [12]

Talking about his approach to concert music, in the same interview Williams admits that the Violin Concerto he completed in 1976 was the first concert piece where he was conscious of developing a personal style, as opposed to his earlier works:

“I think [the Violin Concerto] is about the closest I’ve been able to come to a genuine, idiosyncratic expression. As I was working on that, I was just beginning to feel my wings—much more than the symphony or the wind works. I had more difficulty with style and idiom in those; with the Violin Concerto I was beginning to find a style which… it was still Romantic, but the kind of Romantic Atonality, in an American way, which I was seeking.” [13]

The Concerto premiered on January 29, 1981, with Mark Peskanov as the soloist and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin and was then performed a few days later by the same soloist, orchestra and conductor at the Carnegie Hall in New York City, in a program that also included the Overture to A Life to the Tsar by Mikhail Glinka and Sergej Rachmaninov’s massive Symphony No.2. Music critics were again harsh toward Williams’s work—the prejudice against a film composer stepping into the serious halls of art music was still very strong, as the short review of the work that appeared on the New York Times testifies:

The St. Louis Symphony Orchestra presented the New York premiere of a violin concerto by John Williams in Carnegie Hall last Friday night. The orchestra, conducted by Leonard Slatkin, and the soloist, a young Soviet emigre, Mark Peskanov, probably gave as good an account of the work as it will ever have. But Mr. Williams, who is best known as composer of the scores for ”Jaws,” ”Star Wars,” and some 60 other films, had few ideas, and the Bergian, Hindemithian violin line was tiresomely monotonous. [14]

The work was recorded the same year by Peskanov with the London Symphony conducted by Slatkin, coupled with the premiere recording of the Flute Concerto (performed by LSO’s Principal Flute extraordinaire Peter Lloyd). It’s also interesting to observe that Williams would revise the Violin Concerto in 1998, after Gil Shaham expressed interest in performing it, showing again his attitude in constantly improving what he did in the past. Williams’s Violin Concerto remains one of his most powerful and inspired works for the concert hall.

From early 1980s onward, John Williams’s concert music started to become a more regular presence in his performances. Thanks to his appointment as Music Director of the Boston Pops Orchestra in 1980, the composer became more involved in writing non-film works, but also gained more confidence in presenting his own concert music more regularly as guest conductor with other orchestras, including major institutions like the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Of course the popularity of Williams’s film output soon became the main selling point of his concert appearances in both United States and London, but it was also an opportunity for him to show the audience another side of his musical persona. The composer always saw both sides as complementary to each other, never in conflict. Asked about this specific aspect, Williams told his own thoughts about it, during an interview in 1980:

“My non-film music is atonal and has a more contemporary feeling, though by today’s standards it’s fairly conservative. It has tunes and uses the orchestra in a fairly conventional way, but it’s more daring than what I can get away in a film score, and I hope it’s more idiosyncratic. For me it’s a way of stretching myself and getting rid of certain impulses I couldn’t get rid of in any other way… But I remember the old saying that a lot of things done in the name of the art contain less art than those done in the name of commerce. I continue to try to do both, and I’m not any the less serious about one or the other.” [15]

After several years on the podium of the Boston Pops and a number of new non-film works under his belt (including a spirited Concerto for Tuba and Orchestra written in 1985 for Boston Pops’ principal tuba player Chester Schmitz), the composer felt that it was time also to revisit his Symphony. In February 1986, Williams announced to the Houston Post that his guest performance with the Houston Symphony Orchestra scheduled for April 1987 would be “a new experience”. The composer planned to conduct an entire program featuring almost exclusively his music for the concert hall—the Essay for Strings, the Violin Concerto, and a newly-revised version of the Symphony No.1, almost 20 years after the world premiere performed by the same orchestra. It’s unknown how much the composer revised the work for this performance, if any, but a few weeks before the performance, he decided to replace the performance of the Symphony with selections from his film scores. Asked about the reason of this decision in an interview prior to the performance, the composer almost apologetically answered:

“I guess it was changed because my thinking was that, since I’m more connected with film music, the evening might benefit from that.” [16]

Other than this short statement, there are no other explanations. Given his statements in previous years about his feelings on this work, it’s safe to assume the composer felt the Symphony still wasn’t right, or good enough to be performed in front of an audience. The composer has always been very self-critical about himself, especially about his concert music. In the same interview, talking about the relationship with his younger musical self, Williams added:

“If we look at a letter we wrote two-three years ago, we seem separated from it. Many things we look back on… and anything as personal as writing music… we are constantly being distanced from the moment of creation.” [17]

As much as he tried to improve upon it, John Williams probably kept feeling distanced from the person he was when he wrote the Symphony. And probably for the same reason, the work has never been officially available to perform and it’s not part of the John Williams Signature Edition series on Hal Leonard. It remains to be seen if one day the composer will dust it off and perhaps remodel it completely, or if he prefers to leave it where it is, letting posterity judge it for what it is. Williams’s own overall feelings about his concert music were expressed with his characteristic humbleness in 2012:

“My work in the concert field, my goodness, is a tiny speck set against the great literature that we’ve been given, which is constantly enriched by much finer minds than mine. However, I have found pleasure in writing works not meant for film.” [18]

Williams has always been ready to soften any kind of apparent desire of serious recognition his concert music might suggest to listeners and critics. The truth is that the artist has always found equal joy in writing as much for film as he does for the concert hall, virtually unscathed by the “commerce vs. art” dichotomy that plagued many critical studies over the course of the 20th century. Speaking to film music historian Tony Thomas in 1991, Williams gave a quite definitive answer about this “double life” syndrome typical of the 20th century composer:

“I think that one of the principal goals in writing for film music is to try to create a musical atmosphere that will marry with the film and I think to the degree that one can adapt a personal style or language, that may be the degree of versatility you need to do more than a just a few film scores in a career. I think if a composer, like Copland, for example, who had a very crystallized and wonderfully original and greatly special style of music, would have continued doing film music, he probably would have had to continuate his style in some way or find pieces that were pertinent to his particular grammar. So, I think that kind of versatility is part of being a film composer. At least, that is my kind of film composer. The kind of ability to adapt and perhaps create music within one’s own language, but shaping it and coloring it so it would suit the film. When one is writing concert music, it is a very different set of parameters and different goals that are there. In my own personal case, the few concert works which I have written have been more exercises in self discovery or technical revelations that I might uncover or technical processes that I might want to work out, some of which have application to film technique and others may not have any. So there are certain probable similarities which are inescapable like one’s handwriting or voice, but there are such different goals and limits, present or not present, and one leading to the other that I think the differences in style are explained somewhere in that way.” [19]

The journey into art music and works written for the concert hall by John Williams started more than 50 years ago, and it still continues today with new works and further commissions from soloists and orchestra, including recent compositions such as the incredibly colorful Highwood’s Ghost for cello, harp and orchestra, written for Leonard Bernstein’s 100th Birthday celebrations in Tanglewood.

While the composer might feel it’s just “a tiny speck” again the great classical literature of the past, and despite being less famous than his iconic film music compositions, all of his concert works are superb examples of a composer finding his own voice and discovering new reflections over the course of his lifelong creative journey.

This article wouldn’t have been possible without the immensely helpful support of archivists Libby Rice (London Symphony Orchestra), Terry Edwards (Houston Symphony Orchestra), Carolyn J. Friedrich (Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra). A huge thank you to all of them for their help and assistance.

A special thanks to Miguel Andrade and Emilio Audissino for their help and proof-reading support. Thanks also to Mike Matessino for his valuable historical information about Williams’s early years.

Thanks to Jeff Eldridge for providing much of the reference informations about Williams’s Symphony No.1 through his website johnwilliams.org

References:

[1] “Where John Williams is coming from?”, Richard Dyer, Boston Globe, June 29, 1980

[2] Bernard Herrmann: A Heart at Fire’s Center, Steven C. Smith, University of California Press, 1991

[3] Stan Kenton Conducts the Los Angeles Neophonic Orchestra, 1965, album liner notes by Noel Wedder; Capitol Records

[4] Houston Symphony concert program book, Oct 21-22, 1968, notes by Robert D. Jobe

[5] “John Williams Returns to Band Where He Began 50 Years Ago”, Maj. Michael J.Colburn, The Instrumentalist, June 2004

[6] Eastman Wind Ensemble: Penderecki, Mayuzumi, Williams, 1972, Album liner notes by Donald Hunsberger; Deutsche Grammophon

[7] LSO concert program book, July 7-9, 1972

[8] ibid., 1972

[9] Bernard Herrmann: A Heart at Fire’s Center, Steven C. Smith, University of California Press, 1991

[10] “LSO/Previn: Festival Hall”, Stanley Sadie, London Times, July 10, 1972

[11] “John T. Williams’s First Symphony at the Nottingham Festival”, Gerald Larner, The Guardian, July 9, 1972

[12] “John Williams, pt.2”, Derek Elley, Films & Filming, July 1978

[13] ibid., 1978

[14] “Williams Violin Concerto Has New York Premiere”, Edward Rothstein, The New York Times, February 12, 1981

[15] “Interview with John Williams”, William Livingstone, Stereo Review, June 1980

[16] “Podium part-time home to John Williams”, Carl Cunningham, Houston Post, March 29, 1987

[17] ibid., 1987

[18] “John Williams, the music master”, Clemency Burton-Hill, The Financial Times, August 17, 2012

[19] “A Conversation with John Williams”, Tony Thomas, The Cue Sheet: Journal of the Film Music Preservation Society, Vol.8 No.1, March 1991

Resources:

André Previn’s obituary on LSO.co.uk

https://lso.co.uk/more/news/1207-obituary-andre-previn-1929-30-2019.html

“André Previn’s all-too-brief, tumultuous time with the Houston Symphony”

https://www.houstonchronicle.com/local/bayou-city-history/article/Andre-Previn-Houston-Symphony-1960s-13656231.php

The Los Angeles Neophonic Orchestra

http://allthingskenton.com/table_of_contents/adventures/neophonic/

Eastman Wind Ensemble

https://www.esm.rochester.edu/ewe/about/

“Innocuous as a Film Score: Williams’ Sinfonietta for Winds and Percussion“, by Frank Lehman

http://unsungsymphonies.blogspot.com/2011/10/innocuous-as-film-score-williams.html