In Ibiza, at the beginning of August, the Swedish pop icon Robyn was throwing a party at Pikes, the small, labyrinthine villa where Wham! filmed the video for Club Tropicana. Wearing her “purple rain” disco pants (one resplendent fringed leg, one bare) and wielding a glass of white wine, she snuck a song from her new album in between selections of South African jazz, New York soul and Chicago house. At 2.10am, she climbed on to the DJ booth to shimmy to Barbara Tucker’s deep house classic Beautiful People, phone camera flashes illuminating the sweaty fug.

The night marked the release of Missing U, the first single from Robyn’s first solo album in eight years. Since 2010 – when she released Body Talk, the album that confirmed her as one of the most influential pop artists of the past 20 years – Robyn has lost one of her oldest friends, split from her long-term partner, released three collaborative EPs, questioned whether she should continue making music, reunited with her long-term partner and re-evaluated her entire life. The longer she was away, the more desperate her fans grew, counting the agonising years as if waiting for their husbands to return from war.

Her absence has only underlined her importance. Entire cottage industries have formed to produce the next great star in her image: there is a steady flow of young female artists from beyond the North Sea who are hopefully, vainly labelled “the new Robyn”. In 2013, when 15-year-old Zara Larsson wanted to take her homegrown success stateside, American label executives kept telling her about this other Swedish teenager who broke through there when Larsson was in utero. She didn’t mind. “She’s what I strive to be in a sense of making my own choices and staying true to myself,” says Larsson, whose 2015 single Lush Life went many-times-platinum in countries including the US.

There is something ironic about these efforts to reverse-engineer a figure who has defined herself against the music industry’s lack of imagination. After debuting as a major-label teenage R&B singer in the 1990s, Robyn re-emerged in 2005 with her own independent label and a new electronic sound, scored her first UK No 1 and re-established the X-Factored mainstream as a space for credible pop. At a time when a new generation of music critics were starting to question the received wisdom that pop was less “authentic” than rock, Robyn’s musically adventurous, heart-piercing hits chalked one up for “poptimism”, making indie nerds lighten up and revealing teenybopper fare to be thin gruel.

There was a point after Robyn’s mid-2000s reappearance, says her friend and collaborator Joseph Mount of the British band Metronomy, where you started hearing “more than one Robyn-style track on every pop person’s record”. That is her influence in the ricocheting intensity of Rihanna’s We Found Love and Ariana Grande’s Love Me Harder; in the sledgehammer synths of Taylor Swift’s Welcome to New York. Robyn’s trademark – songs that make you want to dance through tears – runs through Emotion, the acclaimed album by Call Me Maybe singer Carly Rae Jepsen, and Lorde’s Melodrama. When Lorde and her co-producer Jack Antonoff performed on Saturday Night Live last year, they placed a framed photograph of Robyn on the piano. “Robyn has definitely been part of paving the way for pop stars who fall a little to the left of the Top 40 norm,” says British star Charli XCX, who has followed Robyn in pushing pop beyond mainstream norms.

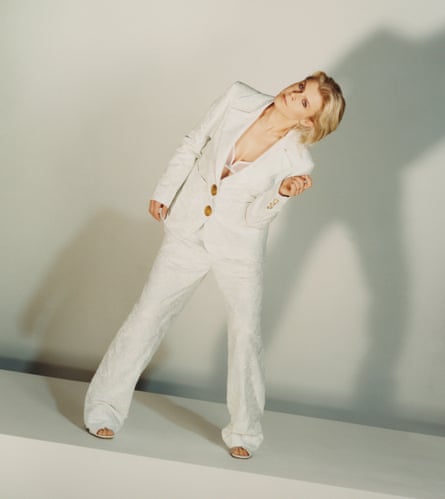

The anticipation around Robyn’s new work couldn’t be greater, but in 2018, at 39 years old, she feels she has nothing to prove – especially not to an ageist industry that, despite being imprinted with her image, may not continue to accommodate her. Two days after the party at Pikes, I met Robyn at the villa she was renting at the top of a slalom-like path through the densely wooded Ibiza hills. As we talked, overlooking the pool and a raked gravel garden, friends emerged from their rave cocoons to receive a plate of eggs from her confidante and collaborator Adam Bainbridge (AKA British producer Kindness). The air smelled like hot cedar. Despite the 31C heat, and having spent the past week clubbing and working, Robyn, wearing a white smock over a complicated white swimsuit, looked unfairly like an embodiment of the surrounding calm.

Soon, her fans will get what they have been waiting for: Robyn’s sixth album, Honey. But it may not necessarily be exactly what they wanted. There were periods, during its making, where Robyn no longer felt at home crafting tidy pop songs. “I was interested in songs that didn’t have a beginning and an end,” she said, “and things that were hypnotic. I wasn’t interested in melody at all.” The album’s pristine pop moments are nestled among exploratory dance music that reflects the hopelessness and ecstasy that informed her time away from the spotlight. She felt no pressure to repeat her biggest hits or embody the hustler persona that informed them. “I didn’t have that killer instinct,” she said.

She knows how desperately fans want her back. Although there was no grand plan, if anything, she hoped her absence might be instructive in an always-on era fed by a constant cultural drip. “When things are so streamlined in your Instagram window,” Robyn said, flicking a phantom phone screen, “I feel like there has to be some complexity. Things can’t just be one thing. It’s more important than ever to just let things be a lot of things at the same time. Not make it too easy.”

Unlike most female pop stars subject to mass idolatry, Robyn’s personal life has never been part of her appeal. (She shrugged off a question about the band on her ring finger.) Instead, her songs function as talismans affirming the nobility of heartbreak and the importance of standing by your convictions without needing to know anything about hers. “Even when she’s being vulnerable, you feel safe being taken on the journey with her,” says comedian and fan Andy Samberg. In a Robyn song, you have the right to desolate heartbreak and the perfectly valid urge to stalk your ex to make triple-sure it is over. This connection is how Robyn always wanted fans to relate to her music, as she did with Kate Bush in the 1980s. But her new album necessitated personal revelations.

In 2010, Robyn started psychoanalysis to unpick how childhood fame had shaped her self-image and relationships. At the time, she felt perpetually guarded: what if she didn’t live up to people’s expectations? Or what if she was too much? For the next six years, she had up to four sessions a week, “a total deprogramming, rebuilding”, until her therapist told her no more. “I needed time to allow myself to dig into things instead of delivering,” she said. That sounds like something said by celebrities who have been to therapy and returned as shiny new pennies, but, in person, Robyn lacks the canned self-awareness of the therapy evangelist, venturing hesitantly but candidly into personal topics. The indomitable cyborg persona that fans (perhaps mistakenly) projected onto her has been replaced by a steady softness: her hair no longer the shocked mullet of recent years, but softly shaped and centre-parted.

Psychoanalysis meant “becoming friends with” elements of her past, namely the guardedness she had felt since finding success as a teenager. “A very paranoid feeling that I think you can avoid if you become famous later in life,” she said, wincing, as always, at associating herself with the word “famous”. It affected her relationships with family, close friends and even herself, she realised, never “allowing myself to be whoever I wanted to be”.

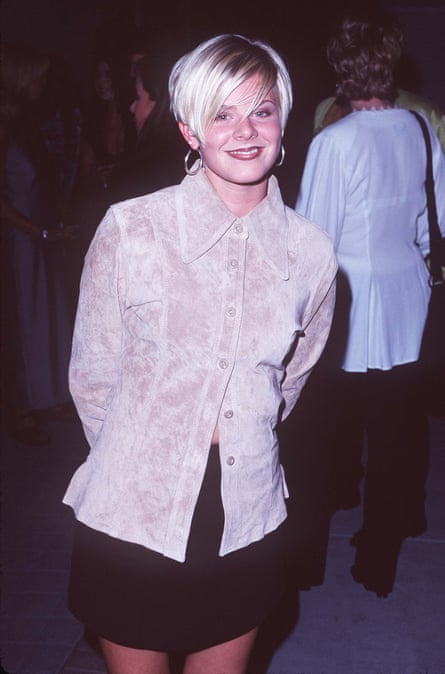

Robin Miriam Carlsson started her career as a teenage popstar fighting to be herself: aged 16, she told one Swedish magazine: “I’m not going to be a product.” She had been discovered three years earlier when the Swedish group Legacy of Sound performed at her school and heard her sing a song she had written about her parents’ divorce. Impressed, Legacy’s Meja Kullersten arranged a meeting with their label, a subsidiary of the major BMG, who immediately signed her. It was 1993: Robyn entered “development”, a shadowy phrase for the period when a label shapes a pop act’s sound, look and personality before they are deemed ready for the world. “I think it’s probably the worst thing you can do to an artist in their teenage years,” Robyn said. “I really feel like, fuck off of it – it’s not anyone’s place to suggest how an artist should develop.”

Despite these misgivings, she remains grateful for being paired with talented Swedish producers, such as Christian Falk, who would become a lifelong friend, and Max Martin and Denniz Pop, the duo who spent the mid-1990s forging pop’s future in their Stockholm studio, writing hits for the Backstreet Boys and *NSync. For Robyn, they combined her love of US R&B with a major-chord-heavy Swedish sensibility, producing the insistent hits Do You Know (What It Takes) and Show Me Love. (Denniz Pop died in 1998, but Martin became the 21st century’s defining pop architect: he has written 22 US No 1s, including songs by Katy Perry and Taylor Swift. Only Lennon and McCartney have had more US chart-toppers.)

Robyn Is Here, her debut album, was a commercial and critical success. As Swift would with country music a decade later, Robyn spotted the potential to insert her generation’s experiences into a bland, bubblegum era: in May 1997, Billboard praised the rarity of Robyn’s “pretty pop fare” making her teenage demographic “focus on, rather than forget, the pained qualities of their coming-of-age experiences”.

Her impact was evident in a sudden wave of white girl R&B singers, from Mandy Moore to Billie Piper. (You can see Robyn’s cool gaze and blonde curtains from the cover of Robyn Is Here rehashed wholesale on Piper’s 1998 debut, Honey to the B.) But her biggest influence may have been provoking the signing of Britney Spears. After the platinum-certified success of her debut in Sweden, the record label Jive had tried to sign Robyn in the US, but she turned them down. The label’s executives swore they would show her how stars were made. The alternative they found was a 15-year-old American named Britney Spears. According to The Song Machine, John Seabrook’s history of contemporary pop songwriting, the head of Jive hoped Britney “could be an American Robyn – a Europop teen queen, with an added dash of girl-next-door”.

Spears was a fan of Show Me Love, which Robyn had written with Max Martin. “We were very eager to work with Max,” Spears’s long-term manager, Larry Rudolph, told me. And Martin was equally keen to work with Spears, imagining her easier to control than the “forceful” Swedish teenager. As Spears’s A&R man recounted in The Song Machine: “Max said, ‘She’s 15 years old; I can make the record I really want to make, and use her qualities appropriately, without her telling me what to do.” He ended up making her 1998 debut single, ... Baby One More Time.

For years a rumour has circulated that Robyn was offered the song before Spears. This wasn’t true, Robyn clarified. Besides, it could never have been a Robyn song: it is too submissive compared with the lyrics that Robyn wrote herself, which preached TLC-inspired self-respect and sex-positivity. It is true that after signing Spears, her label demonstrated – just as its executives had promised – how to transform teenage blonds into pop icons. Britney became a cautionary tale about extracting massive commercial gain from a young woman at massive personal cost. Robyn had two US hits and disappeared. But she didn’t need to sing the 90s’ most iconic song to change the course of pop music.

Robyn entered the music industry with a feminist outlook inherited from her mother, who was nervous about her eldest child’s career: facile pop was the antithesis of her childhood with their travelling futurist theatre group. Robyn’s willfulness made her a compelling pop star, but this side of her was steadily worn down. Working in the US as a teenager, she felt isolated. There were no collaborators her age, no recourse if she was burned out. Adults treated her as a troublesome child: in a 2011 Swedish documentary, a male RCA associate recalled pinning her to the floor when she was upset. (In the same documentary, Robyn said she was glad she gave those “SOBs” a hard time.) She learned how to be a “good girl”, she told me. “When you become famous super young, you learn how to behave by the rules because you’re the one that has to take the stress. But that also creates a barrier that I really didn’t want.”

Robyn returned to Sweden in 1998 to make her introspective second album, My Truth. Although it went platinum in Sweden, it was not released in the US when she refused her American label’s request to omit two songs about having an abortion. “I guess Robyn had moved in a direction they didn’t expect,” her manager told Billboard. Over the next few years, her career drifted. In 2001, she signed with Spears’s label, which she had turned down in her teens, but her 2002 album Don’t Stop the Music never came out in the US.

In 2003, when it looked like she might end up as a footnote in pop history, Robyn travelled to France for a writing session with avant-garde Swedish electronic duo the Knife. The experience showed her the possibility of a future outside the machine. Siblings Karin and Olof Dreijer were her age and treated her like an equal. They explained how they ran their own label – a revelation to club kid Robyn, unfamiliar with indie culture – and together produced one song, Who’s That Girl, a tough, electropop rebuke to the idea of the “good girl”. “Good girls are happy and satisfied,” Robyn sang. “I won’t stop asking until I die.”

Her A&R representative hated it, but helped Robyn buy out of her contract. In 2004, she convened a retreat at her summer house to brainstorm her next moves with three trusted associates. She wrote her name on a whiteboard and conducted “really surgical” talks about how she was perceived: her discomfort with being cast as a “role model” in the Swedish media, which followed her around demanding inspiring soundbites, and how that determined her label’s suggested collaborators. Robyn did not find this forensic dissection weird. “It was so nice,” she said. “The artist version of me didn’t feel like me – it really felt like an alter-ego.”

From the retreat came her independent label, Konichiwa, and the plan for her career’s second phase. Artists have long abandoned success to pursue passion projects in obscurity, but for Robyn, escaping her major label didn’t mean forsaking popularity. “The people I knew who had done this on their own, like the Knife, still had a much smaller or less commercial audience,” she said. “I didn’t have any role models of artists that were in the same playing field as me – making expensive videos, travelling, marketing and promoting an album.” She did not sleep for six months. “It was a big challenge, but also I didn’t feel like I had a choice.”

By 2005, pop had spent a decade in bubblegum purgatory, bookended by the Spice Girls and Simon Cowell’s televised karaoke empire. But, in Britain, a welcome weirdness was sneaking into the mainstream. Brilliant producers found major pop acts to be willing vessels for their groundbreaking ideas: Xenomania with Girls Aloud, bootleg pioneer Richard X with S Club 7’s Rachel Stevens and the Sugababes.

Robyn wanted a true partnership from her new collaborators, not someone who would “stuff hits down her throat”, said Klas Åhlund, a Swedish punk and relatively inexperienced producer who met Robyn through her manager. Pairing Simon and Garfunkel-style songwriting with club music became their mission. “That thing that happens at 3am in a dark space was, at the time, so far removed from the mainstream,” said Åhlund.

Their first song was called Be Mine. Åhlund had started a demo that excited Robyn because it evoked her beloved Prince’s When You Were Mine. They added a spoken-word breakdown, “trying to find heartbreaking things you would say to an ex-partner’s new girlfriend or boyfriend”, said Åhlund. “There was this one line: ‘You got down and tied her laces’ that was so ordinary and not pop, but it felt interesting and true.”

Åhlund wrote on guitar. Robyn had no intention of making guitar music. “I let him have it for a while,” she said, “but then I played him Cloudbusting by Kate Bush, and said: ‘Can we make it into strings instead?’” Åhlund conceded.

The song reached No 3 in Sweden and cemented their style: of emotional hyper-specificity (more Pet Shop Boys than the reigning Pussycat Dolls) and structural minimalism, removing every extraneous element until a song “nearly collapses, like Jenga”, said Åhlund. They developed an exacting approach that he called “Kubrickian”. “I’m always watching rock documentaries where people try to make out that they” – they being Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones – “were insane because they mixed Beat It 22 times. I’m like, yeah, because that’s how you do it. We’ve always been a bit like that.”

Be Mine also established Robyn’s emotionally intense perspective. “You never were, and you never will be mine,” she sang with surprising triumph. She stripped away every vocal mannerism – what musician Todd Rundgren praised as her “straight-ahead, unaffected” approach. Robyn was obsessed with stalkers – giving even her most lovelorn protagonists subversive agency, their longing never submissive. “Even if I’ve never been a stalker, I think that’s a very common tendency when you’re really heartbroken,” she said.

Robyn’s self-titled 2005 album arrived in Sweden a month after Be Mine, and was voted the 39th best of the year by influential US music publication Pitchfork. (The album wasn’t released in the US until 2007, but the site’s assiduous staff found it online.) Bar one Kylie Minogue album and Norwegian producer Annie’s 2004 debut, devoutly indie Pitchfork had never covered pop – though to Americans reared on strict radio genre segregation, Robyn didn’t register as chart fare. She re-emerged as Pitchfork was embracing hip-hop producers such as Timbaland and Kanye West. Drawing from her teenage love of rap – even though her major-key choruses remained steadfastly European – she didn’t seem so different.

Pitchfork’s Robyn evangelism placed synthpop on the same level as earnest, artsy acts such as Arcade Fire and Sufjan Stevens. “The old rock critic mindset, which regarded certain approaches or characteristics as inherently more nourishing than others, started to feel constricting and narrow-minded,” says Pitchfork founder Ryan Schreiber.

In 2007, when the album was released in the UK, Robyn’s distinction from mainstream pop became clearer. The year’s biggest songs were subtle as sequinned thongs or wet as washcloths. Robyn’s single With Every Heartbeat felt arrestingly sincere. “We could keep trying / But things will never change,” she sang: “So I don’t look back / Still I’m dying with every step I take / But I don’t look back.” Part of its genius, says Berklee College of Music musicologist Dr Joe Bennett, is that it never resolves to the home key we are primed to expect, stoking her lack of resolution.

It became Robyn’s only UK No 1 single, and started something. Girls Aloud covered it, their OTT warbling revealing the power of Robyn’s vulnerable clarity, while Åhlund (despite not working on Heartbeat) was invited to work with Minogue and Spears. (They wanted the Robyn “hot sauce”, he said.) Robyn was instrumental in repopularising “sonically interesting” music, said Metronomy’s Mount, likening the effect to Björk’s influence on Minogue and Madonna in the 90s. “Back in the day, you were defined as one kind of artist and you stayed there,” says Annie. “And especially for female artists, you are some sort of cheap pop star. Robyn showed that you can do more traditional pop and something a bit more underground and still be real and respected.”

By the time she finished touring at the end of 2008 – a three-year cycle thanks to the staggered international release dates – Robyn felt burned out. She decided to split her fifth release into smaller bites to sustain her creativity. In June 2010, she released an EP, Body Talk Pt 1. Three months later came Pt 2, then in November a third instalment, all three then collected as a Body Talk album. Her approach suited a moment when changing technology meant that people were increasingly forsaking albums for individual songs.

Her relentless synthpop and knack for alchemising heartbreak into pure energy established her as the keeper of pop’s gold standard, combining “the emotional release of really intimate, beautiful songwriting and the ecstasy of dance music,” says singer Maggie Rogers. One of the album’s defining songs was Call Your Girlfriend – essentially, a set of instructions to the singer’s new boyfriend on how to break up with his soon-to-be-ex, but delivered with such benevolence to make this borderline psychopathic sentiment irresistible. Traces of stalker DNA also ran through another of the album’s breakout songs, Dancing on My Own. After it featured in an early episode of HBO’s Girls, it became an unofficial theme song for the show, says music supervisor Manish Raval. He recalled being in the edit suite before anyone knew of the show, watching Lena Dunham’s protagonist dancing away heartbreak to the song. “That was when we realised, we’re working on something big here,” he said. Finding triumph in rejection helped make Robyn an LGBTQ icon: Calum Scott’s mournful cover of Dancing on My Own was a massive hit in 2016. “Personally, I’ve always fallen for the straight guys, so the lyrics alone speak to my life,” he said.

Next to cartoonish Katy Perry, absurdist Lady Gaga and melodramatic Florence + the Machine, Robyn seemed more like Prince or David Bowie, a pioneer defying gender stereotypes. “She had this shifted perspective that didn’t make her register as a predator or a victim,” says Sara Quin of Canadian duo Tegan and Sara, who list Body Talk as an influence. “She was scrappy, sexy and even when she was hooking up with your boyfriend, she was worrying about your feelings.”

Robyn and Åhlund didn’t register that they were writing future classics. Every song spawned a new idea, said Åhlund, estimating that they wrote 22 songs that year. “I don’t think we stopped to pat ourselves on the back too much.”

Had Robyn maintained that work rate – three releases every five months – Body Talk 60 would now be on the way. Clearly, that is unsustainable. Even so, she did not intend to wait so long before releasing another album, but then her long-term relationship with film-maker Max Vitali fell apart, her friend Christian Falk died, and grief forced her into a period of contemplation that would transform her approach to making music.

Pop geeks remember Robyn’s first phase for her association with Max Martin. But for Robyn, her bond with Falk, who worked on her first two albums, was more significant. He was one of the only adults who treated her with respect and taught her to love all kinds of music without shame. After he was diagnosed with terminal cancer, Falk, Robyn and the musician Markus Jägerstedt formed La Bagatelle Magique in 2014. Their one EP was released in the summer of 2015, a year after Falk’s death. Later that year, Robyn and Jägerstedt cancelled a planned tour after one date. “It was much harder singing these songs than I thought,” she said then.

Robyn and Vitali reunited after two years. But in Ibiza, Robyn described that period as “hitting an all-time low”. She had never experienced such pain before because she had always used work as a coping mechanism. “I used to feel empty and lonely when I didn’t have the thing” – she made a drilling sound – “that would replace the disabling sadness.” This time her tenacity became physically unsustainable: there were periods where she could not get out of bed. “Between 2014 and 2016, I was just like, extremely sad,” she said plainly. “Like really, really just not able to be in the spotlight.”

She was still in psychoanalysis, which, coupled with grief, made her question everything: her purpose, reality itself. “What’s everything made of?” she wondered. She gestured across the pool. “That tree’s gonna die, too? Even things didn’t feel solid any more.” She did not know if she would make music again. “It’s not like my feelings are more interesting than others,” she said.

Being single was hard but occasionally pleasurable. She spent time away from her home in Stockholm, which felt too family oriented for single life. London, Paris and Ibiza were better. Clubbing was important. One night, she heard DJ Koze’s 2015 minimal techno track XTC at a club in Los Angeles, where she also lives. Robyn was sober when she heard these eight minutes of serotonin-washed bliss overdubbed by a voice that soberly asks: “Is a drug like the lie / And meditation the truth / Or am I missing something / That could really help me?” It hit her like a sermon. Robyn interpreted the question as: “How do I find happiness? How do I find peace?” she said.

When the urge to make music returned, around the time she heard XTC, it was “primal”, said Robyn. Despite her coveted musical style, she had come to feel like her sound was not entirely her own, so she taught herself production. Initially, she had to fight doubt: “How much can I be the author of my own voice?” But with knowledge came empowerment. And: “So much fun,” she emphasised. “And then I could start writing the songs that I wanted to write, all of a sudden, instead of adapting my way of songwriting to someone else’s music.”

She had her own ideas about the groove her new music demanded. Perfect pop songs with a “beginning, a middle and an end” held no interest during this period of skewed reality; open-ended, trance-like dance music appealed because it felt like “just getting into a feeling”. She also learned to dance samba – the music makes her cry. It’s the rocking motion, she realised, less static than her trademark juggernaut pop. “I wanted to be moved in a different way,” she said.

From 2014 to 2015, Robyn spent a year alone in the Stockholm studio she shares with Åhlund, which has a pale pink floor to instil calm. She didn’t write “album 6” on a whiteboard and plot outwards, but searched for sounds that evoked XTC’s trippy euphoria and the sensuality she had ascribed to honey, a new obsession that had come to represent her “free, happy place” while figuring out how to feel good about herself, something she had lost.

Only once she found it, in a song that she called Honey (“Never had this kind of nutrition,” she sings), did she introduce her new collaborators. Not all of them ended up making tangible musical contributions, but the partnerships became intimate friendships, based on musical exploration and big nights out, which saturate the album. British producer Kindness, who uses they/them pronouns, was arrested by her precision: recently Robyn woke them up in the middle of the night, asking for more files for the 16th mix of the pair’s song. Kindness titled the email “Send to Robin Immediately”, so that is what she called the track. But Kindness was equally struck by her deftness with fleeting emotion. “I didn’t understand the extent to which you could catch it in a butterfly net and turn it into a song,” they said. That emotional openness initially left Metronomy’s Joseph Mount feeling exposed, “like we were in secondary school doing drama”, he said.

Mount formed part of Robyn’s core unit with Åhlund during the three years she spent on the album. She demurred when asked whether she ever has to fight for her authority today, before diplomatically saying how pleased she was that she and Åhlund had maintained their partnership even though she is now involved with production. “That could have been what breaks a relationship,” she said. Åhlund thought Robyn’s new skills allowed her to approach the music without having to start by confronting intense emotional experiences in lyrics. “She would sit for hours moving a hi-hat pattern around,” he said. “You can get very deep into the music by doing that.” Once she started singing, to find the most relaxed possible mode she would often record lying down on a fluffy yellow rug that looked like Big Bird.

Robyn calls Honey “a diary in grief”, even though the process became deeply pleasurable. “It felt like I was taking care of myself doing it,” she said. The songs appear in the order they were written, tracing the journey from desolation to ecstasy and reconciliation. The lowest point is Missing U, the first Robyn single that sits with loss rather than trying to metabolise it and sprint onwards. Amid joyful nods to club greats like Lil Louis’s French Kiss and Crystal Waters’ Gypsy Woman, the highest point is Because It’s in the Music, a radiant disco tribute to the songs that bring up bittersweet memories. Even if you have never loved and lost, it will convince you that you did, and that this song was your song. (Hers was UB40’s Don’t Break My Heart.)

The final track, Ever Again, shreds Robyn’s weepy dancefloor blueprint: “Never gonna be broken hearted, ever again!” she declares. Imagine Billy Bragg declaring he was never going to sing about socialism, ever again. Or Adele saying she was never gonna be broken-hearted, ever again (something she wasn’t allowed to do on her last album despite having found domestic bliss). “For me that song is like, yes, things might not work out, but I’m not gonna break again,” Robyn said.

In early September, a month after Ibiza, Robyn was kneeling on a stool in Jägerstedt’s studio in the Stockholm neighbourhood Södermalm. Chin in palm, elbow on desk, she concentrated on a new song bolting from the speakers. She looked childlike, bouncing her bare legs to the beat. For someone who smokes a lot of tarry cigarettes, even while recovering from a cold, she is the picture of milk-fed health.

They were in the earliest stages of production for her upcoming tour, trying to work out the setlist. On Robyn’s laptop screen was a Spotify playlist of her old material titled “sign of the times”. Every so often, she would lean across Jägerstedt, sitting at the desktop, to amend a colour-coded spreadsheet. The lyrics from 2010’s Hang With Me felt weird after Missing U, she told him. “Even if they work together, they mean something different.” They blended songs together to see whether the beats matched and a segue might work. More important was how to interweave her new album – a complete, linear story – with her older material without creating contradictions.

Robyn has had an unusually long pop career, especially for a female musician. There is no template for her: Madonna still struggles for creative control; MIA has swerved in and out of the mainstream. She knows how many young pop acts cite her as an influence. Recently, she bumped into Martin in Los Angeles. They had dinner and she mentioned her new music. “He’s so cute, like: ‘You’ve done a new album? Can I listen, please?’” she said, impersonating his nervous intensity as we ate lunch in a vegan cafe after the production meeting. “He told me: ‘So whenever I have a female artist come into my studio, they usually put your album on the table, and they’re like: “I wanna make this!”” I don’t know who he meant. But he said that’s happened quite a lot, and that he’s like: ‘Well, fuck you, go and work with her then!’ Which I thought was very sweet.”

Emulating Robyn’s sound is possible; maintaining her creative control is harder. Long after she had proved herself, the micromanagement from industry executives could still reach absurd lows. “When I did the video for Handle Me [in 2007],” she said, “I had quite strong eyebrows, which now isn’t a weird thing at all – everybody has eyebrows – but back then it was, like, considered being super unsexy, and I remember my American label wanting me to redo the video.” (She refused.)

Selling an attitude of independence has been crucial to the allure of most major female pop stars since Madonna, but there is a chasm between the carefully curated appearance of sovereignty – a mainstay of branded feminism – and actually running your business. “Getting that control takes a lot of stamina, and a lot of drilling, drilling, drilling,” said Robyn. Daring to ask questions and revealing your lack of knowledge makes you insecure, even vulnerable. “It’s not a sexy process, although the result is, of course, something that’s very desirable for people. I think getting there has been something that I’m admired for by the industry, but people that have been very close to it, they haven’t been very impressed.”

Sometimes maintaining her independence has meant closing off certain possibilities. Even once Robyn gained control, it felt safer to project steeliness than to be vulnerable. “I could have been much softer or more sensual if I knew how to do it,” she said. With Honey, she was trying to show that side of herself while mindful of contributing to the commercialisation of female sexuality. (“That’s also a power tool – it’s a way of dominating, demanding attention through a commercial way of looking at yourself.”)

Robyn turns 40 next June; when she performed Missing U at BBC Radio 1’s annual Ibiza party, days after her do at Pikes, it was to tanned teenagers who were not born when she released her debut. The single has slowly crept up the playlist at Radio 1, a station aimed at 15-29-year-olds. Twenty years ago, when Madonna turned 40, newspapers called her “grandma”. That much, thankfully, has changed: her recent 60th birthday was greeted with rightful admiration. But Robyn is still standing at the frontier of what’s possible for female pop artists outside their coveted 20s. “I’m super conscious that I’m looking older and that I’m feeling older,” she said, with enthusiasm rather than despair. “That I’m not naturally realising what the next step in the music industry is – when you’re younger, you just know what you need to do to climb.”

Her situation highlights one of the paradoxes of pop: so much of the business is built on selling the kind of self-belief that only truly comes with age, yet few artists are allowed to mature on their own terms. In today’s see-what-sticks era, pop stars that are not instant successes are sidelined or exiled to development hell. Longevity – especially for women – often depends on a willingness to protect an enduring brand, as Spears is doing with her extensive Las Vegas residency, or to disappear into the background to write for younger artists.

Robyn is not counting on commercial success with Honey. “I don’t know if I will be let through the filters,” she said. But she is also not interested in editing herself to try and slip through: retouching photos, cropping songs for different formats. “I don’t know if my idea of what’s interesting and groundbreaking now will be even remotely understandable for someone that’s below 30,” she said, again, in a way that suggested she could not wait to find out. Contrary to pop’s governing obsession with youth, the evidence of Robyn’s career suggests that 40 may be the perfect age for a pop star, bringing with it the kind of freedom worth waiting for.

This article was amended on 10 March 2021. We incorrectly misgendered the producer Kindness due to an error while preparing the article for publication.