When he’s interviewing guests on his podcast, does Rob Brydon, I wonder, feel a twinge of professional jealousy? Talking to Matthew MacFadyen about Succession, or Steve Coogan or Mark Gatiss about their many projects? Jennifer Saunders or Alison Steadman or Kenneth Branagh? It’s not all comics and actors – Johnny Marr, Noel Gallagher and Chris Martin have all appeared on Brydon &. “There’ll be occasional moments,” he admits, “but it will be something very specific, but not generally. I’m not a ‘grass is greener’ person. I’m a ‘look around you, this is good’ person.” He smiles. “I sometimes wish I were a bit more jealous actually, it might make me a bit more get-up-and-go.”

The podcast originated in lockdown, when a producer friend suggested he start a YouTube channel, interviewing famous friends (show me a better-connected man in showbiz). “It was something to do. It gave me a chance to be a little bit creative, to make something.” Spotify picked it up, and now the Amazon-owned podcast company Wondery.

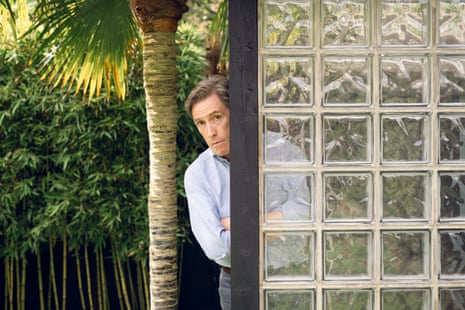

It wasn’t a huge leap for Brydon, who is best known as an actor, in shows such as Gavin and Stacey and The Trip, and a panel show host. He started on BBC Radio Wales as a broadcaster. Another early job was on a film show, interviewing actors; later, he had his own chatshow. The podcast, he says, is “very straightforward, simply a conversation, and we’re not especially sensational because that’s just not me.” Recently he unintentionally strayed on to a sensitive topic with one guest, “and they became quite uncomfortable. It was interesting, because I had two thought processes going on.” He didn’t want his guest to feel bad. “But there was another part of my brain, I’m rather ashamed to say, that was going ‘this would be good’. I didn’t like thinking that because that’s not what I want to be. I suspect we’ll edit that out.”

Brydon doesn’t like conflict, he says. As a child, growing up in south Wales, he always wanted to be an entertainer. He liked, he says, “making people happy. I like to make them laugh. Why would you not want to?” It’s probably the reason he started his 2011 autobiography with a clear explanation that he would not be writing about his divorce from his first wife (he remarried, and now has five children), and why potentially contentious subjects are usually headed off with humour. On the subject of retrospectively appraising comedy shows for their non-PC content, as Gavin and Stacey has been, he laughs and says it is “fascinating, isn’t it? Because if you take it to its nth degree, I think pretty soon we’re going to have to stop talking about Henry VIII, because of the way he treated women, which I think was appalling. But he seems to be getting away with it at the moment. I’ve not heard anybody mention him.” In the past he has said Coogan, his friend and collaborator, who is far more political and outspoken, questions why he never puts his head above the parapet on anything.

Which is not to say Brydon is not reflective. It’s partly age – he’s 58 – and I think partly the format of his podcast, often taking in the whole scope of a performer’s career, and which tends to be unrushed and meandering – funny too, obviously – scored by Brydon’s soothing accent. Then there’s The Trip, Michael Winterbottom’s brilliant comedy in which he and Coogan, playing extreme versions of themselves, travel around “reviewing” restaurants while pondering big things like ageing, ambition, mortality and who has the most awards.

On the subject of getting older – “our old friend mortality” as he put it in one podcast episode – he smiles. “I try to see the positives of it. I think it’s quite useful to remind yourself ’twas ever thus, and it can be very easy to think that this is something that’s been lumped on you alone. But I’ve got nothing to complain about.” As an actor, Brydon says with a mock grimace, he is constantly reminded of the poignancy of time passing, when people send him old photographs they’d like him to sign. “Actors and comedians are always being reminded of former glories – if you’re lucky enough to have former glories.”

Brydon’s glories were quite a long time coming – he was 35 when he got his break – and for a while he wasn’t sure he would make it. His early success as a DJ on Radio Wales allowed him to buy a small house in Cardiff. “I felt like I was Elvis. I’d got Graceland.” Then he was let go when a new editor joined, and for the next few years he struggled, getting into debt, and defaulting on his mortgage. He kept a note of the pittance he was earning from voiceover work in notebooks which he still has; Brydon appears to be a meticulous note-keeper, also holding on to a ring-binder full of rejection letters from agents and casting directors.

When a job on a shopping channel came up – he remembers he was in bed in the afternoon when the call came in – he leapt at it. Did he worry he was jeopardising whatever credibility he had, amid the booming 90s comedy scene? He has never worried about being cool, he says. “I’ve never been one of the cool guys. I’ve always thought it is a folly to concern yourself with that, because that’s fashionable, it comes and goes. One of my bugbears is something being described as a ‘guilty pleasure’. I want to say ‘Oh, go fuck yourself’. What is this high position where you’re deeming whatever it is …?”

Anyway, he says, “You’ve got to remember where I was coming from. I grew up, a very provincial life, and I think I was quite young for my age.” In his podcast episode with Coogan, the Alan Partridge creator talks about not going to see Grease when it came out because he thought it was for the masses. “If you’d said to me ‘the masses’, I wouldn’t have known what that was,” says Brydon. “It wasn’t my world.” He would naively write to people hoping to be cast – to Richard Curtis for Four Weddings and a Funeral, to Kevin Costner for Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves. He smiles. “Unsurprisingly, I didn’t get a reply from either of them. So that’s the backdrop.”

after newsletter promotion

That naivety probably helped, too – he always thought, despite everything, that he would have a career, even when the shopping channel went bust “so then I was an ex-shopping channel person”. He had what he calls “little tricks” – the impersonations, the talent for improv – but also persistence. “Thank God I had determination then,” says Brydon. “I think the thing that’s in everybody that makes it is they are tenacious, they don’t give up. I know a lot of talented people who haven’t done as well as they wanted to, but every talented person I know who has done well is also bloody tenacious. I think that’s more important in the equation.”

It was his home-filmed sketches that caught the eye of Coogan, whose production company made Brydon’s show Marion and Geoff, in which he played Keith Barret, a taxi driver dealing with his divorce. There aren’t many performers like Brydon who can move between so many worlds – from panel shows, relentless cheesy advertising voiceovers, and a musical live show, to niche dark comedy such as the BBC show Human Remains with Julia Davis, theatre roles or four series of partial improv shepherded by Michael Winterbottom.

I ask him what he has learned from his hugely successful podcast guests and he struggled to distil it. What has he learned, then, from his own eclectic career? “I can answer that. It’s probably different for other people. I have contemporaries who remain very driven, and they produce wonderful work, but it does mean that they are working a hell of a lot, and they are travelling a lot, and I don’t want that.” He is happy that he has not, he says, “sacrificed my family for my career”. When he was younger, watching his contemporaries zoom past him, “I was striving, I would say I was very driven, and thought that the work on its own would bring you happiness. And I don’t feel that any more.”

Brydon & is on Amazon Music and Wondery+

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion