What Would Happen If Mount Rainier Erupted?

Hot Rock And Volcanic Ash Would Hurtle Down The Mountain At 100 Miles Per Hour

Photo: C.G. Newhall / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainOne of the first hazards that comes from a volcanic eruption is the presence of ash and rocky debris, which is hurled from the mouth of the volcano at incredible speed. This is coupled with a lava flow, and depending on how steep the slopes are upon which the lava flows down the mountain, it can speed up the debris to as fast as 100 mph. Carolyn Driedger, a geologist who has specialized in studying volcanoes like Rainier, has described this in frightening detail:

The lava flows encounter those very steep slopes and make avalanches of hot rocks and gas that are hurtling down the mountain maybe 100 miles per hour or so.

Fortunately, the large boulders and smaller rocks wouldn't shoot much further than the volcano's base, but their impact upon landing would be incredible.

Pyroclastic Flows Would Produce A Deluge Of Meltwater

Photo: Walter Siegmund / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.5Mount Rainier has long been called the most dangerous volcano in the United States, and it's not because of its size or potential explosive force - it's due to the large glacier sitting at its top. The glaciers sitting at the mountain's top are descendants from the Pleistocene age, and while they aren't as large as they were during the last Ice Age, they are still massive chunks of ice, which would almost immediately melt when the volcano finally erupts.

According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), there are 25 distinct glaciers covering 92 square kilometers (35 square miles) of the volcano. When the volcano is dormant, those glaciers regularly melt to provide the headwater for five major rivers. That's a lot of potential water sitting at the top of five major waterways, many of which contain hydroelectric dams and important bridges.

Once the volcano erupts, those glaciers will melt into a massive deluge of meltwater, which will have no other path than down into those rivers. This will inundate the waterways, which would likely shut down dams, create power outages, devastate roads, and significantly impact the natural landscape for hundreds of miles.

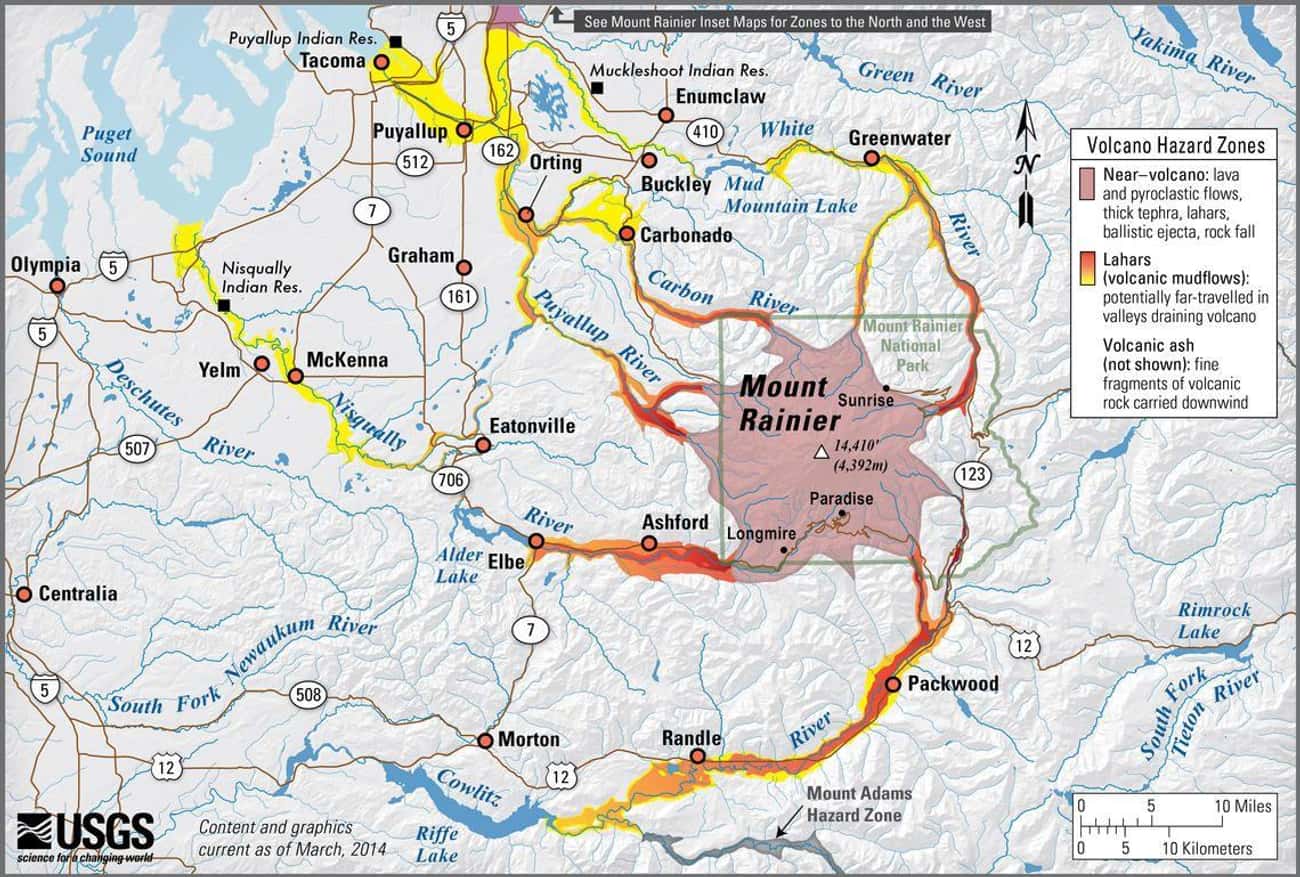

Rushing Meltwater Could Lead To Perilous Lahars Reaching As Far As The Puget Sound

Photo: Walter Siegmund / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.5When a volcano like Rainier erupts and melts the glaciers covering it, the flowing water does more than simply go downhill. Most of that water will mix with pyroclastic material and rocky debris to create a lahar. Lahars are incredibly ruinous, and like avalanches composed of snow, they grab anything they pass and incorporate it into the flow. This leads to a great deal of devastation, and depending on the slope, they can flow tens of meters per second, which can amount to a steep 22 mph or more. According to Janine Krippner, a volcanologist at Concord University, “Lahars can lift houses. They can overtake a bridge. They can take the bridge with it.”

Because a lahar can pick up more and more material as it passes (e.g. cars, trees, houses, etc.), they tend to pick up speed and move further than a typical lava flow. Lahars leave a great deal of material as they pass, which makes it easy to determine where a modern lahar might flow. The National Lahar was formed by an eruption some 2,200 years ago, and the deposits suggest the path a new one might take.

Carolyn Driedger described the National Lahar by pointing out various aspects of what it left behind, “We’re seeing this wall of rocks. Big boulders the size of basketballs, and it looks like something that a human being has constructed.” As a lahar plummets down a slope, giant boulders are picked up and smashed against one another to create smaller, faster debris. Because a lahar will likely flow along the same path into the rivers, it could extend as far as the Puget Sound and directly impact the city of Seattle, WA, via post-lahar sedimentation.

Airborne Volcanic Ash Would Disrupt Aviation

Photo: USGS / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainWhen a volcano erupts, it typically spews a cloud of toxic ash into the air. Depending on the size and scale of the eruption, this could entail a plume of material, which flows up into the air as high as the upper atmosphere. This can lead to several problems, including a disruption to electronic communication systems, the blanketing of that ash on a large area when it finally drops to the ground, and a large suspension of air traffic.

Aviation shuts down in the immediate area due to a number of factors, including a reduction in visibility, the disruption of communication, and the threat of ash flowing into a jet intake, which would almost certainly lead to a crash.

Volcanic ash is composed of tiny fragments of pulverized rock, volcanic glass, and minerals. It is an incredible risk to flight safety, especially when those flights are conducted at night. When a plane comes into contact with ash, the cinders can scratch up a cockpit, melt inside an engine's combustion chamber, clog fuel nozzles, and lead to a total engine failure. Because this is a real concern to flight safety, aviation is rerouted or canceled in any area considered to be under threat from volcanic ash, and since that could be hundreds of radial miles, the impact can be massive.

Volkswagen-Sized Chunks Of Debris Would Be Blasted Into The Air

Photo: R. Clucas / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainPart of what makes volcanos like Mount Rainier so devastating is their crater at the summit. That rock has to make way for the explosive flow of magma rising to the surface, and if Rainier blows like most volcanoes of its size and type, that crater will blow from the mountain with a great deal of force. This will lead to large chunks of rock shooting from the crater to the valley below. According to geologist Carolyn Driedger:

You can envision that there would be blocks half the size of the visitor’s center here at Paradise or the size of Volkswagens and fine grain material being blasted into the atmosphere and then falling back on the snow’s surface.

Most of those boulders won't make it too far from the mouth of the volcano, but they will likely break up and flow along the lahar, which could take them much further than the base of the volcano.

Trees Would Be Pulled Down By Flash Floods

Photo: Stephan Schulz / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0You might think a deeply rooted tree would be safe from the flow of water coming down a volcano's slope, but there isn't much that can withstand the force of a lahar. When Mt. Rainier erupts, you can all but guarantee all those old-growth trees won't stand a chance.

When the lahar comes into contact with a tree, it picks it up as if it were a toothpick on the ground, then carries it along with the flow until it is deposited. That could be anywhere along the path of the lahar, but if the eruption of Mt. St. Helens is any indication with the above picture, the surface of Mount Rainier will lose all of its trees along the path of lava and lahars.

This can occur even when Mount Rainier doesn't erupt. On October 2, 1947, Kautz Creek saw the largest debris-flow event recorded throughout history. The road below the mountain was covered with 28 feet of mud, rocks, and trees. This occurred following an extensive and heavy rainfall, but it's easy to see how quickly debris can flow down Mount Rainier.

Houses Would Be Ripped From Their Foundations And Bridges Would Topple

When it comes to the ruinous power of a volcano like Mount Rainier, the risk of lava flow is actually fairly mild when compared to that of a lahar. Lahars are unstoppable forces, which careen down the mountain into the countryside with exceptional force. When the lahars from Mount Rainier flow down the mountain, they will pick up and wipe out everything in their path.

This means that trees, houses, most buildings, and even bridges will be picked up and taken along for the ride. Even though lahars are a known concern, the path they would flow has been heavily settled and densely populated. They have been described as "flowing concrete, and they destroy or bury most manmade structures in their path."

Tacoma Would Face A Food And Supply Shortage

Photo: Lyn Topinka (USGS) / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainOne of the key cities, which would face widespread problems as a result of an eruption, is Tacoma. The city lies between the mountain and Seattle along the path a lahar would likely take. While the lahar would likely steer clear of most of the city structures since it will follow the path of the Puyallup River, it would still manage to bury numerous roads, and any bridges along the path would likely be wiped out.

Because aviation would be mitigated for some time following the eruption, this means that food and supplies, which normally come in via air or by road, would be halted. The only path to Tacoma would be by sea, and it would likely become congested and difficult to manage, if not completely blocked. This could lead to shortages of food and medical supplies.

Ultimately, this is a modern city, but access to Tacoma would be severely limited. Its primary ports are located on the Puget Sound, which would see some impact from the lahar's sedimentary deposits. The city would recover and disaster plans are in place, but it would take a while before the problems caused by the eruption were completely mitigated.

Lava Would Flow To The Boundaries Of The Park

Photo: Kelvin Kay / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainWhile the real concern of an eruption is a lahar, there is still going to be a flow of lava coming from the mountain. Fortunately, the molten rock won't find its way to the city of Seattle or even very far from the mountain's base. It will only flow in limited areas to the boundaries of Mount Rainier National Park. That still amounts to a large area consisting of some 236,381 acres (369.3 square miles; 956.6 square kilometers), but the lava won't flow to fully encompass the entire park - much of the land will remain untouched.

This is due to the shape of the mountain and its rivers, which offer a natural course for lava and lahars to flow. Most of the lava will flow along these paths before it cools and solidifies. While there will be considerable devastation to the ecosystem, it will recover over time.

Orting, WA, Wouldn't Survive

Photo: USGSThe city of Orting, WA, is a small town situated approximately 30 miles from Mount Rainier. That may seem like a lot, but it also happens to be sitting atop the remains of several layers of ancient lahar deposits. If history is any indication, the lahars - which will flow from an eruption - will follow the same path they previously took, which means the entire city of Orting will be wiped out or significantly impacted following an eruption.

While this may sound like a depiction of doom for the town's 6,700 residents, an eruption from Mount Rainier would come with a great deal of advanced notice. Earthquakes, the opening of fissures, and many other signs will point to a probable eruption long before it happens. Lahar sirens are programmed to go off should the slightest hint of vibration come from sensors installed all over the mountain. This means that everyone in the town would be evacuated prior to the eruption, and while most of the city will likely be wiped out, no person in Orting should perish or come away with injuries as a result.

Infrastructure Like Dams & Freshwater Sources Would Likely Be Wiped Out

Photo: Joe Mabel / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0Another major problem posed by an eruption would be its impact to infrastructures like power supply systems and freshwater supplies. When a lahar rushes down a river, it doesn't just break apart bridges and everything in its way, it deposits a significant amount of debris along the way. This results in two distinct effects: Water sources are contaminated, and dams lose the ability to intake water properly due to congestion.

This degrades their ability to provide power and can leave them completely inoperable until the debris and contamination can be removed. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the impact of a lahar could be lessened by dams along rivers, but that mitigation comes with its own problems:

Dams and reservoirs on several rivers could lessen the extent of future lahars by trapping all or much of the flow, but they could also increase a lahar's extent if a lahar displaced reservoir water and caused dams to fail.

Lahar Deposits Would Result In Billions Spent Dredging The Material

Photo: Tom Casadevall, USGS / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainThe landscape surrounding Mount Rainier is full of ancient lahar deposits, and while they have shaped the lands across the region, modern civilization won't support just leaving that debris where it settles. Removing the deposits will cost billions of dollars and could take years to complete. The amount of material is massive and could be as thick as 40 to 50 feet in some areas.

The debris, which will ultimately settle into the Puget Sound, as well as along the Puyallup River and other waterways, will need to be dredged. This will also require a great deal of money and resources to manage. Fortunately, much of the debris will be naturally eroded by rivers and streams as they reestablish their channels, but the material may still move downstream to deposit in large quantities, which will ultimately need to be removed.

Ultimately, the costs and result of an eruption may not result in a large loss of life, but it will leave a lasting impact on the local area, which will take years to overcome.