FreightWaves Classics is sponsored by Old Dominion Freight Line. Click to find out how we can help your business keep its promises.

National Hispanic Heritage Month

National Hispanic Heritage Month is observed annually from September 15 to October 15. It celebrates “the histories, cultures and contributions of American citizens whose ancestors came from Spain, Mexico, the Caribbean and Central and South America.”

Hispanic Heritage Week began in 1968 under President Lyndon Johnson and was expanded by President Ronald Reagan in 1988 to cover a 30-day period beginning on September 15 and ending on October 15. It was enacted into law on August 17, 1988.

September 15 is significant because it is the anniversary of independence for Latin American countries Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. In addition, Mexico and Chile celebrate their independence days on September 16 and September 18, respectively. Also, Columbus Day which is October 12, falls within this 30-day period.

FreightWaves Classics also celebrates National Hispanic Heritage Month. A recent article profiled Federico Peña, the first Hispanic-American to serve as U.S. Secretary of Transportation; another focused on Henry Frederick Garcia, a U.S. Coast Guard trailblazer; and the third profiled Irene Rico, who had a distinguished career with the Federal Highway Administration.

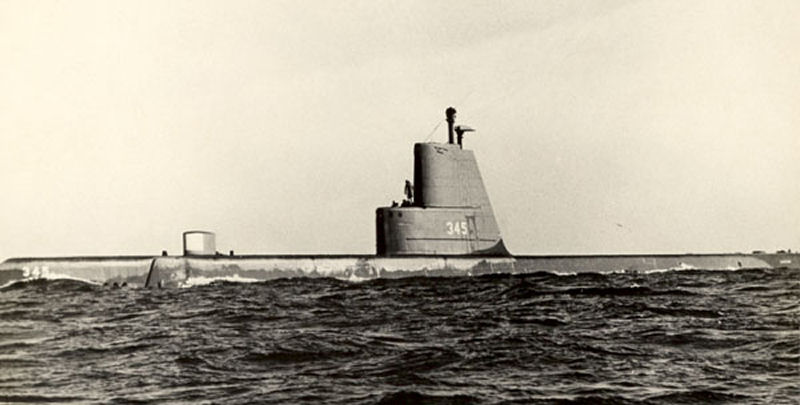

(Photo: history.navy.mil)

As of December 2021, approximately 67,000 active and reserve sailors of Hispanic heritage serve in the U.S. Navy. Military service by Hispanic Americans dates to the Civil War. This FreightWaves Classics article profiles one of those 67,000 who made a lasting difference.

Rafael Celestino Benítez (March 9, 1917 – March 6, 1999) was born in Juncos, Puerto Rico. After graduating from high school he attended the United States Naval Academy thanks to an appointment by Puerto Rico’s Resident Commissioner. Benítez graduated from the Naval Academy in 1939 and was assigned to submarine duty.

World War II

Beginning as an ensign, Benítez saw action during World War II aboard the submarines USS Dace and USS Grenadier. For his actions, he was twice awarded the Silver Star as well as the Bronze Star.

At the rank of lieutenant commander, he commanded the submarine USS Halibut from February 15, 1945, to May 19, 1945. The Halibut had been launched just prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and was commissioned on April 10, 1942. The submarine and its crews had an impressive war record, which included sinking 12 Japanese ships. However, it was damaged beyond reasonable repair on its tenth and final war patrol, which ended on December 1, 1944. As its commander Benítez sailed the Halibut from San Francisco to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where the submarine was decommissioned on July 18, 1945.

On January 29, 1946, just a few months after the end of World War II, Lieutenant Commander Benítez became the commander of the USS Trumpetfish. Inspired by his father who was a judge, Benítez then attended Georgetown Law School, earning his law degree in June 1949.

The Cochino incident

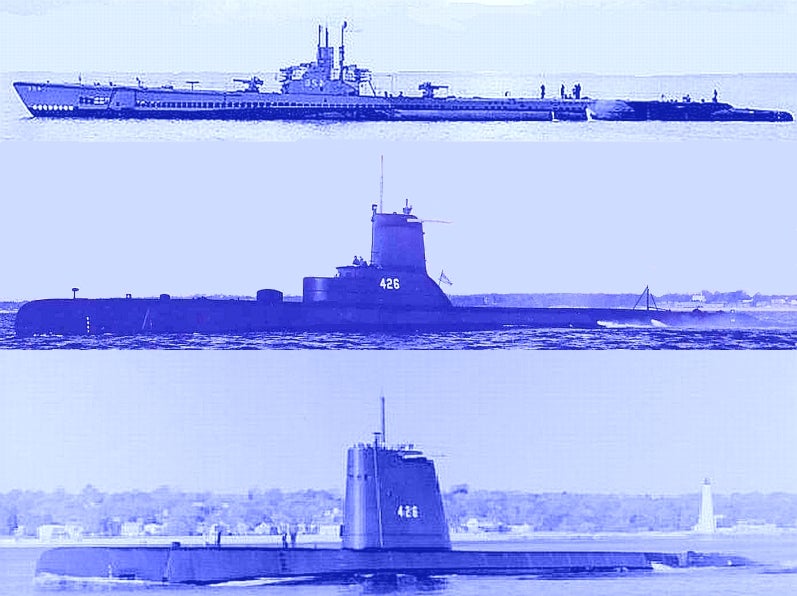

The summer of 1949 was relatively early in the Cold War era. Benítez was named the commander of the submarine USS Cochino. On August 12, 1949, the Cochino and the USS Tusk left Portsmouth, England for what was termed a cold-water training mission. However, according to “Blind Man’s Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage,” the two diesel submarines were equipped with snorkels that allowed them to spend longer than normal periods underwater. Relatively invisible to the Soviet Navy, and equipped with electronic gear designed to detect far-off radio signals, the Cochino and Tusk were part of a U.S. intelligence operation.

(Photo: U.S. Navy courtesy of oneternalpatrol.com)

The U.S. submarines were charged with eavesdropping on communications that revealed tests of submarine-launched Soviet missiles that might soon be armed with nuclear warheads. The two submarines took part in the “first American undersea spy mission of the Cold War.”

However, on August 25, one of the Cochino’s 4,000-pound batteries caught fire and began emitting hydrogen gas and smoke. Benítez ordered the Cochino to surface and had dozens of crew members tie themselves to the submarine’s deck rails with ropes while he directed others to fight the fire. Benítez tried to save the Cochino while also saving his crew from the toxic gasses. With winds tearing at the ropes holding the crew, he ordered them to form a pyramid on the ship’s open bridge (designed to hold only seven men).

There were two casualties on the Cochino. Lt. Cmdr. Richard M. Wright survived despite severe burns. Robert Philo, a civilian sonar expert, sought to reach the Tusk on a raft to report on the fire. The high seas caused Philo and 11 of the Tusk’s crew to be knocked overboard. Philo and six of the Tusk’s crew drowned.

The ocean calmed overnight, and the Tusk approached the Cochino. Its crew, with the exception of Benítez, boarded the Tusk. He was persuaded to board the Tusk just two minutes before the Cochino sank off the Norwegian coast.

According to an account in the New York Times decades later (April 5, 1997), “On September 20, 1949, the Soviet publication Red Fleet said the Cochino had been ‘not far from Murmansk’ and suggested that it had been seeking military information. On September 23, President Harry S. Truman, confirming fears that had led to Commander Benítez’s mission, announced that the Soviet Union had detonated its first nuclear device.”

Final years of U.S. Navy career

Benítez was named chief of the U.S. Navy mission to Cuba in 1952. He remained in that position until 1954, and in 1955 he became commander of the destroyer USS Waldron. Under his command the Waldron operated along the East Coast and in the West Indies.

In 1959, Benítez retired from the Navy after 20 years of service. He was promoted to the rank of rear admiral because he had been decorated for heroism in combat.

Post-Navy career

Benítez became Pan American World Airways’ vice president for Latin America. He also taught international law and was associate dean at the University of Miami Law School, as well as being named dean of the university’s graduate school of international studies. During his years at the university’s law school, Benítez founded the Graduate Program for Foreign Lawyers, now known as the LL.M. Program in Comparative Law. He also inaugurated the “Lawyer of the Americas” (the predecessor of the Inter-American Law Review) and started the Masters Program in Inter-American Law for U.S. Lawyers.

Benítez also wrote “Anchors,” a compilation of ethical and practical maxims, which was published in August 1996. On March 15, 2000, the University of Miami School of Law began the Rafael C. Benítez Scholarship Fund to support the studies of foreign graduate students.

(Photo: valor.militarytimes.com)

Benítez died in Easton, Maryland, on March 6, 1999. He was survived by his wife and three children.

FreightWaves Classics thanks the Naval History and Heritage Command, NavSource Naval History, valor.militarytimes.com