History of Pune

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2023) |

Pune is the 9th most populous city in India and one of the largest in the state of Maharashtra.

Although area around Pune has history going back millennia, the more recent history of the city is closely related to the rise of the Maratha empire from the 17th–18th century. Pune first came under Maratha control in the early 1600s when Maloji Bhosale was granted fiefdom of Pune by the Nizam Shahi of Ahmednagar. When Maloji's son, Shahaji had to join campaigns in faraway southern India for the Adil Shahi sultanate, he selected Pune for the residence of his wife, Jijabai and younger son, Shivaji (1630-1680), the future founder of the Maratha empire.[1] Although Shivaji spent part of his childhood and teenage years in Pune, the actual control of Pune region shifted between the Bhosale family of Shivaji, the Adil Shahi dynasty, and the Mughals.

In the early 1700s, Pune and its surrounding areas were granted to the newly appointed Maratha Peshwa, Balaji Vishwanath by Chhatrapati Shahu, grandson of Shivaji. Balaji Vishwanath's son, and successor as the Peshwa, Bajirao I made Pune as his seat of administration. That spurred growth in the city during Bajirao's rule which was continued by his descendants for the best part of 18th century. The city was a political and commercial center of the Indian subcontinent during that period.[2] This came to an end with the Marathas losing to the British East India Company during the Third Anglo-Maratha War in 1818.

After the fall of Peshwa rule in 1818, the British East India Company made the city one of its major military bases. They established military cantonments in the eastern part of the city, and another one at nearby Khadki.The city was known by the name of Poona during British rule and for a few decades after Indian independence. The company rule came to an end when in 1858, under the terms of Proclamation issued by Queen Victoria, the Bombay Presidency, along with Pune and the rest of British India, came under the direct rule of the British crown.British rule, over more than a century, saw huge changes in the social, political, economic, and cultural life of the city. These included the introduction of railways, telegraph, roads, modern education, hospitals and social changes. Prior to the British takeover, the city was confined to the eastern bank of the Mutha river. Since then, the city has grown on both sides of the river. During British rule, Pune was made into the monsoon capital of the Bombay presidency. Palaces, parks, a golf course, a racecourse, and a boating lake were some of the facilities that were constructed to accommodate the leisurely pursuits of the ruling British elites of Bombay presidency that stayed in the city during the monsoon season, and the military personnel. In the 19th and early 20th century, Pune was the center of social reform, and at the turn of the 20th century, the center of Nationalism. For the latter, it was considered by the British as the center of political unrest against their rule. The social reform movement by Jyotiba Phule in the latter half of 1800s saw establishment of schools for girls as well as for the Dalits. In 1890s, nationalist leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak promoted public celebration of Ganesh festival as a hidden means for political activism, intellectual discourse, poetry recitals, plays, concerts, and folk dances.

The post-independence era after 1947 saw Pune turning from a mid-size city to a large metropolis. Industrial development started in the outlining areas of the city such as Hadapsar, Bhosari, and Pimpri in the 1950s.The first big operation to set up shop was the government run Hindustan Antibiotics in Pimpri in 1954.The area around Bhosari was set aside for industrial development, by the newly created Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) in the early 1960s. MIDC provided the necessary infrastructure for new businesses to set up operations. The status of Pune was elevated from town to city, when the Municipality was converted into Pune Mahanagar Palika or the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) in the year 1950.This period saw a huge influx of people to the city due to opportunities offered by the boom in the manufacturing industry, and lately in the software field. The influx has been from other areas of Maharashtra as well as from outside the state. The post-independence period has also seen further growth in the higher education sector in the city. This included the establishment of the University of Pune (now, Savitribai Phule Pune University) in 1949, the National Chemical Laboratory in 1950 and the National Defence Academy in 1955.The Panshet flood of 1961 resulted in a huge loss of housing on the riverbank and spurred the growth of new suburbs. In the 1990s, the city emerged as a major information technology hub.

Early and medieval[edit]

The first reference to Pune region is found in two copper plates dated to 758 and 768 AD, issued by Rashtrakuta ruler Krishna I. The plates are called "Puny Vishaya" and "Punaka Vishaya" respectively.The plates mention areas around Pune such as Theur, Uruli, Chorachi Alandi, Kalas, Khed, Dapodi, Bopkhel and Bhosari.The Pataleshwar rock-cut temple complex was built during this time.[3] Pune later became part of the Yadava Empire of Deogiri from the 9th century. During this time, it was called as "Punekavadi" and "Punevadi". In 2003, an accidental discovery of artefacts from the Satvahana period in the Kasba peth area of the city has put the origin of settled life in the area to the early part of the first millennium.[4][5]

The Khalji dynasty overthrew the Yadavas in 1317. This started three hundred years of Islamic control of Pune. The Khalji dynasty was succeeded by another Delhi sultanate dynasty, the Tughlaqs. A governor of the Tughlaq for the Deccan revolted and created the independent Bahamani sultanate. The Bahamanis, and their successor states, collectively called the Deccan sultanates, ruled Pune region between 1400 and early 1600s. During the Islamic era, the city was called "Kasabe Pune". A defensive wall around the city was built by Barya Arab, a commander of either the Khaljis or the Tughlaqs, in the early 1300s. Traditional accounts state that the temples of Puneshwar and Narayaneshwar were turned into the Sufi shrines of Younger Sallah and Elder Sallah respectively.[6] During this period, Muslim soldiers and few civilian Muslims lived within the town walls, on the eastern bank of the Mutha River. The Brahmins, traders, and cultivators were pushed outside the town walls.[3][7][note 1] The Hindu saint, Namdev (1270–1350) is believed to have visited the Kedareshwar temple. The Bengali saint, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu visited the place during the Nizamshahi rule.[3] Under the Bahamani and early Nizamshahi, towards the end of 15th century, Pune became a center for learning of Sanskrit scriptures.[3]

Maratha rule[edit]

Pune first came under Maratha control in the early 1600s. However, control shifted between the Bhonsle family, the Adil Shahi dynasty, and the Mughals, for most of the century. In the early 1700s, Pune and its surrounding areas were granted to the newly appointed Maratha Peshwa, Balaji Vishwanath. It remained with his family until his great-grandson Bajirao II was defeated by the British East India Company in 1818.

Bhosale family fiefdom (1599–1714)[edit]

In 1595 or 1599, Maloji Bhosle, the grandfather of Maratha empire founder,Shivaji, was given the title of "raja" by Bahadur Nizam Shah II, the ruler of the Ahmednagar Sultanate.[8] On the recommendation of Nizam's Vazir, Malik Ambar, Maloji was granted the jagir (fiefdom) of the Pune and Supe parganas, along with the control over the Shivneri and Chakan forts.

In 1630–31, Murar Jagdeo Pandit, a general of Adil Shahi of Bijapur attacked Pune and razed it to the ground by using ass-drawn ploughs, as a symbol of total dominance.[3][note 2] Soon afterwards, Shahaji, the son of Maloji, joined the service of Adil Shahi, and got his family's jagir of Pune back in 1637. He appointed Dadoji Konddeo as the administrator of the area. Dadoji slowly rebuilt the city, and brought back the prominent families who had left the city during the destruction by Murar Jagdeo.[9] Shahaji also selected Pune for the residence of his wife, Jijabai and son, Shivaji, the future founder of the Maratha empire. The construction of a palace, called Lal Mahal, was completed in 1640. Jijabai is said to have commissioned the building of the Kasba Ganapati temple herself. The Ganesh idol consecrated at this temple is regarded as the presiding deity (gramadevata) of the city.[10]

Pune changed hands between the Mughals and the Marathas many times during the rest of the century. It remained under Shivaji's control for the most part of his career, however, he operated from mountain forts like Rajgad and Raigad. Recognizing the military potential of Pune, the Mughal general Shaista Khan and later, the emperor Aurangzeb further developed the areas around the city.[11]

Peshwa rule (1714–1818)[edit]

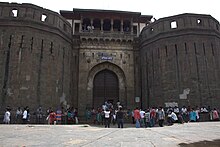

In 1714, the Maratha ruler Shahu appointed Balaji Vishwanath, a Chitpavan Brahmin, as his Peshwa. Around the same period, Balaji was gifted the area around Pune by the grateful mother of one of Shahu's ministers, the Pantsachiv, for saving the latter's life.[12] In 1720, Baji Rao I, was appointed Peshwa, as a successor to his father, by Shahu.[13] Bajirao moved his administration from Saswad to Pune in 1728, and in the process, laid the foundation for turning what was a kasbah into a large city.[14][15] Before Bajirao I made Pune his headquarters, the town already had six "Peths" or wards, namely, Kasba, Shaniwar, Raviwar, Somwar, Mangalwar, and Budhwar.[16] Bajirao also started construction of a palace called Shaniwar Wada on the eastern bank of the Mutha River. The construction was completed in 1730, ushering in the era of Peshwa control over the city. The city grew in size and influence as the Maratha rule extended in the subsequent decades. During this period, in addition to being the administrative capital of the Confederacy, the city also became the financial capital of the Confederacy. Most of the 150 bankers or "savakars" in the city belonged to the Chitpavan or Deshastha Brahmin communities.[17]

The city gained further importance as the Maratha dominance increased across India under the rule of Bajirao I's son, Balaji Baji Rao, also known as Nanasaheb. After the disastrous Battle of Panipat in 1761, Maratha influence was curtailed. At that time, the Nizam of Hyderabad looted the city. The city and the empire recovered during the brief reign of Peshwa Madhavrao I. The rest of the Peshwa era was full of family intrigue and political machinations. The leading role in this was played by the ambitious Raghunathrao, the younger brother of Nanasaheb who wanted power at the expense of his nephews, Madhavrao I and Narayanrao. Following the murder of Narayanrao on the orders of Raghunathrao's wife, in 1775, power was exercised in the name of the son of Narayanrao, Madhavrao II, by a regency council led by Nana Fadnavis for almost the rest of the century.[18] For most part, the Peshwa rule saw the city elites coming from the Chitpavan Brahmin community. They were the military commanders, the bureaucrats, and the bankers, and had ties to each other through matrimonial alliances.[19]

Pune prospered as a city during the reign of the peshwas. Nanasaheb constructed a lake at Katraj, on the southern outskirts of the city, and an underground aqueduct, which is still operational, to bring water from the lake to Shaniwar Wada.[20] Later in the century, the city got an underground sewage system in 1782, that ultimately discharged into the river.[9][21] On the southern fringe of the city, Nanasaheb built a palace on the Parvati Hill.In the vicinity of the hill, he developed a garden called Heera Baug, and dug a lake with a Ganesh temple on an island in the middle of the lake. He also developed new commercial, trading, and residential localities called Sadashiv Peth, Narayan Peth, Rasta Peth, and Nana Peth. The city in the 1790s had a population of 600,000. In 1781, after a city census, household tax called Gharpatti was levied on the more affluent, which was one-fifth to one-sixth of the property value.[22]

Under Peshwa rule, law and order was exercised by the office of the Kotwal. The Kotwal was both the police chief, magistrate, as well as the municipal commissioner. His duties included investigating, levying, and collecting of fines for various offenses. The Kotwal was assisted by police officers who manned the chavdi or the police station, and the clerks collected the fines and the paid informants who provided the necessary intelligence for charging people with misdemeanor. The crimes included illicit affairs, violence, and murder. Sometimes, even in case of murder, only a fine was imposed. Inter-caste or inter-religious affairs were also settled with fines.[23] The salary of the Kotwal was as high as 9000 rupees a month, but that included the expense of employing officers, mainly from the Ramoshi caste.[24] The most famous Kotwal of Pune during Peshwa rule was Ghashiram Kotwal. The police force during this era was admired by European visitors to the city.[25]

The patronage of the Brahmin Peshwas resulted in great expansion of Pune with the construction of around 250 temples and bridges in the city, including the Lakdi Pul and the temples on Parvati Hill.[26] Many of the Maruti, Vithoba, Vishnu, Mahadeo, Rama, Krishna, and Ganesh temples were built during this era. The patronage also extended to 164 schools or "pathshalas" in the city that taught Hindu holy texts or Shastras. However, the schools were open to men from the Brahmin castes only.[27] The city also conducted many public festivals. The main festivals were Holi, the Deccan New year or Gudi padwa, Ganeshotsav, Dasara, and Dakshina. Holi at the court of Peshwa, used to be celebrated over a five-day period. The Dakshina festival celebrated in the Hindu month of Shraavana, when millions of rupees were distributed, attracted Brahmins from all over India to Pune.[28][29] The festivals, the building of temples and the rituals conducted at temples, led to religion being responsible for about 15% of the city's economy during this period.[15][30][31]

The Peshwa rulers and the knights residing in the city also had their own hobbies and interests. For example, Madhavrao II had a private collection of exotic animals such as lions and rhinoceros, close to where the later Peshwe park zoo was situated.[32] The last Peshwa, Bajirao II was a physical strength and wrestling enthusiast. The sport of pole gymnastics or Malkhamb was developed in Pune, under his patronage, by Balambhat Deodhar.[33] Many Peshwas and the courtiers were patrons of Lavani, a genre of music and folk-dance popular in Maharashtra. A number of composers of it, such as Ram Joshi, Anant Phandi, Prabhakar, and Honaji Bala, came from this period.Ram Joshi also composed a powada praising the wonders of Pune itself.[34] The dancers used to come from the castes such as Mang and Mahar.[35][36] Lavani used to be an essential part of Holi celebrations at the court of Peshwa.[37]

The Peshwa's influence in India declined after the defeat of Maratha forces in the Battle of Panipat, but Pune remained the seat of power. The city's fortunes declined rapidly after the accession of Bajirao II to power in 1795. In 1802, Pune was captured by Yashwantrao Holkar in the Battle of Poona, directly precipitating the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803–1805. The Peshwa rule ended with the defeat of Bajirao II by the British East India Company, under the leadership of Mountstuart Elphinstone, in 1818.

British rule (1818–1947)[edit]

In 1818, Pune and rest of the Peshwa territories came under the control of the British East India Company. The company rule came to an end when in 1858, under the terms of Proclamation issued by Queen Victoria, the Bombay Presidency, along with Pune and the rest of British India, came under the direct rule of the British crown.[38]

City development[edit]

British rule, over more than a century, saw huge changes that were seen in all spheres, social, economic, and others as well. The British built a large military cantonment to the east of the city.[39][note 3] The settlement of the regiments of the 17 Poona Horse cavalry, the Lancashire Fusiliers, the Maratha Light Infantry, and others, led to an increase in the population. Due to its milder weather, the city became the "Monsoon capital" of the Governor of Bombay, thus making it one of the most important cities of the Bombay Presidency. The old city and the cantonment areas followed different patterns of development, with the latter being developed more on European lines to cater for the needs of the British military class. The old city had narrow lanes and areas segregated by caste and religion.[40] For many decades, Pune was the center of social reform and at the turn of the century, the center of Indian Nationalism. British era also saw development on the western bank of the Mutha river, in the vicinity of the village of Bhamburde.

The population of the city was previously decreasing with the declining fortunes of the Peshwa rule. The population at the beginning of British rule was estimated at around 100,000, and it declined further as the city lost its stature as the seat of a major power. In the 1851 census, the population of the old city (excluding cantonment) was down to 70,000. The population increased subsequently, following the introduction of railways, to 80,000 in 1864, 90,000 in 1872, and 100,000 in 1881. The population of greater Poona (including Cantonment, Khadki, and surrounding villages like Ghorpadi) in 1881 was 144,000. By 1931, it had increased to 250,000. In the 1890s, there was a loss of population during the bubonic plague, due to mortality from the disease as well as people leaving the city to escape the disease. The population bounced back in the following decades, due to the introduction and acceptance of vaccination by the Indian population of the city. During the British era, the vast majority of the old city population was Marathi-speaking Hindus. Other significant minorities were Muslims, Christians and Roman Catholics, Parsis, Jews, Gujaratis, and Marwadis.[7][42] During this period, the city population was heavily segregated by caste and economic status.[43]

The Poona Municipality was established in 1858. The cantonment area had its own separate administration from the beginning, and is governed separately even today. Unlike the Bombay Municipal council, the Poona Municipality had two-thirds members elected. In case of Bombay, it was only half the members. Due to the colonial government of the Presidency setting up property and educational qualifications to hold office, majority of the seats on the corporation were held by Maharashtrian Brahmins, who accounted for 20% of the city's population in the late 1800s. A significant number of seats were also held by non-Maharashtrian Hindus (Gujarati, south Indian, etc.) and Parsis.[45] Social reformer, Jyotirao Phule was appointed to the council in the 1870s.[46] The position of District Collector was created by the East India company at the beginning of its rule, and has been retained after Independence. Pune and the Pune district also had a collector, who had broad administrative power of revenue collection and judicial duties. When Pune and the Peshwa territories came under the company rule, Governor of the Bombay Presidency, Mountstuart Elphinstone wanted to retain many practices of the old order, including justice.[47] He continued the practice of Panchayat (a jury of local elders) to adjudicate in civil cases, however, the litigants preferred the parallel courts modelled on the English judicial system.[48][49] Trial by jury was introduced in Pune in 1867.[50]

For most of the British era, Pune remained a poor cousin of Mumbai when it came to industrialization. There were, however, a few industrial concerns active at the turn of the 20th century, such as a paper mill, metal forge works, and a cotton mill. An ammunition factory was set up in Khadki in 1869.[51] Printing contributed significantly to the city's economy, due to the presence of large number of educational establishments in the city. To a major extent, manufacturing was a small-scale business. Cotton and silk weaving were major industries that grew in the 19th century. The same was true of brass and copper-ware.[52] The latter actually developed after the advent of railways made importation of sheet metal easier.[7][53] Other small industries included jewelry, beedi-making, leather-works, and food processing. Towards the end of the British era, movie-making had become a significant business, with eminent studios like the Prabhat Film Company located in the city.[54] In the early years of the British rule, an open-air vegetable market used to be held outside the Shaniwar Wada. This shifted to an indoor place built by the Poona Municipality, which was inaugurated in 1886. The market was named after the then Governor of Bombay, Lord Reay, and served as retail and wholesale market in addition to being the municipal office. There was also an older market-district called Tulshi Baug, close to the vegetable market that sold a variety of household items.[55]

During the first and second Anglo-Maratha wars, it used to take 4–5 weeks to move materials from Mumbai to Pune. A military road constructed by the company in 1804 reduced the journey to 4–5 days. The company later built a Macademized road in 1830, that allowed mail-cart service to begin between the two cities.[57] Railway line from Bombay, which was operated by the Great Indian Peninsula Railway (GIPR), reached the city in 1858.[58][59] In the following decades, the line was extended to places farther east and south of the city. In the east, GIPR extended its line till Raichur in 1871, where it met a line of Madras Railway and thereby connected Poona to Madras.[60] The Pune-Miraj line was completed in 1886. The completion of the Metre-gauge Miraj line turned the city into an important railway junction. The Bombay-Poona line was electrified in the 1920s. This cut the travel time between the cities to three hours and made it possible to make day-trips between the cities for business or leisure, such as the wealthy people from Bombay visiting the city to see the Poona races.[61] Although railways came to Pune in the middle of the 19th century, public-bus service took nearly ninety-years to follow suit. Unlike Mumbai, Pune never had a tram service. The first bus service was introduced in Pune in 1941, by the Silver bus company. This caused huge uproar amongst the Tanga carriers (horse-drawn carriage) who went on strike in protest.[62] Tangas were the common mode of public transport well into the 1950s. Bicycles were choice of vehicle for private use in the 1930s.[63]

Given the importance of Pune as a major Military base, the British were quick to install the instant communication system of Telegraph in the city in 1858.[64] The Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona (2 pts) of 1885 reports that, in 1885, the city had its own telegraph office in addition to the GIPR company's telegraph service. The city was a post-distribution hub for the district. There were two post offices in the city, which in addition to mailing services, offered money order and savings bank services. In 1928, a beam relay station was installed in Khadki to beam radiotelegraph signals for Imperial Wireless Chain system.[65]

Areas east of Pune receive much less rainfall than the areas in the west of city, adjacent to the Sahyadri mountains. To minimize the risk of drought in the low rainfall areas, a masonry dam was built on the Mutha river at Khadakwasla in 1878. At that time, the dam was considered one of the largest in the world. Two canals were dug on each bank of the river, for irrigating lands to the east of the city. The canals also supplied drinking water to the city and Pune cantonment.[66] In 1890, Poona Municipality spent Rs. 200,000 to install water filtration works.[67]

Electricity was first introduced in the city in 1920.[68] In the early part of the 20th century, hydroelectric plants were installed in the Western Ghats between Pune and Mumbai. The Poona electric supply company, a Tata concern, received power from Khopoli on the Mumbai side of the ghats, and Bhivpuri plants near the Mulshi dam.[69] The power was used for the electric trains running between Mumbai and Pune, for industry and domestic use.

To cater for the religious and educational needs of the British-Christian soldiers and officers from the Anglo-Indian, Goan-Luso-Indian and Eurasian (mixed ancestry) communities, the early colonial period saw the building of many Protestant and Catholic churches and schools, such as The Bishop's School (Pune), Hutchings High School, and St. Mary's School, Pune. St. Vincent's High School, St. Anne's School (Pune) were other schools founded in the 1800s to cater to the Catholic community.[70]

In the 1820s, the company government set up a Hindu college, to impart education in Sanskrit. In the 1840s, the college started offering a more contemporary curriculum. The college was then renamed as Poona College, and later Deccan College.[71] The 1800s also witnessed tremendous activity in setting up schools and colleges by early nationalists. For example, Bal Gangadhar Tilak was one of the founders of the Deccan Education Society.[72] The society set up the New English school as well as the renowned Fergusson College. Another nationalist, Vasudev Balwant Phadke was co-founder of the Maharashtra Education Society. Both the Deccan and Maharashtra education society run numerous schools and colleges till date, in Pune, and in other cities, such as Abasaheb Garware College. The Shikshan Prasarak Mandali was responsible for setting up the Nutan Marathi Vidyalaya school for boys in 1883, and the SP College for higher education in 1916. The colonial era also saw the opening of schools for girls and the Untouchable castes. The pioneers in this task were the husband and wife duo of Jyotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule, who set up the first girls' school in Pune in 1848.[73] Later in the century in 1885, Justice Mahadev Govind Ranade and R. G. Bhandarkar founded the first and renowned girls' high school in Pune, called Huzurpaga.[74] SNDT Women's University, the first university for women in India, was founded in Pune by Dhondo Keshav Karve in 1916.[75] Early during British rule, in the 1830s, the "Poona Engineering Class and Mechanical School" was established to train subordinate officers for carrying out public-works like buildings, dams, canals, railways, and bridges.[76][77][78][79][80][81] Later on, in the year 1864, the school became the "Poona Civil Engineering College." The number of courses were increased to include forestry and agricultural subjects, which led to its name being changed to Poona College of Science. All non-engineering courses were stopped by 1911, and the college was renamed as Government College of Engineering, Poona. Lord Reay Industrial Museum, which was one of the few industrial museums in colonial times, was established in Pune in 1890.[82]

Western Medical education started in Pune with the establishment of the BJ Medical school in 1871. The Sassoon Hospital was also started around the same time, with the help of the philanthropist Sassoon family in 1868.[83] A regional mental asylum at Yerwada was established in the late 1800s.[84]

Poona was a very important military base with a large cantonment during this era. The cantonment had a significant European population of soldiers, officers, and their families. A number of public health initiatives were undertaken during this period ostensibly to protect the Indian population, but mainly to keep Europeans safe from the periodic epidemics of diseases like Cholera, bubonic plague, small pox, etc. The action took form in vaccinating the population and better sanitary arrangements. The Imperial Bacteriological laboratory was first opened in Pune in 1890, but later moved to Muktesar in the hills of Kumaon.[85] Given the vast cultural differences, and at times the arrogance of colonial officers, the measures led to public anger. The most famous case of the public anger was in 1897, during the bubonic plague epidemic in the city. By the end of February 1897, the epidemic was raging with a mortality rate twice the norm and half the city's population had fled. A Special Plague Committee was formed under the chairmanship of W.C. Rand, an Indian Civil Services officer. He brought European troops to deal with the emergency. The heavy handed measures he employed included forcibly entering peoples' homes, at times in the middle of the night and removing infected people and digging up floors, where it was believed in those days that the plague bacillus bacteria resided.[86] These measures were deeply unpopular. Tilak fulminated against the measures in his newspapers, Kesari and Maratha.[87] The resentment culminated in Rand and his military escort being shot dead by the Chapekar brothers on 22 June 1897. A memorial to the Chapekar brothers exists at the spot on Ganesh Khind Road. The assassination led to a re-evaluation of public health policies.[88] This led even Tilak to support the vaccination efforts later in 1906. In the early 20th century, the Poona Municipality ran clinics dispensing Ayurvedic and regular English medicine. Plans to close the former in 1916 led to protest, and the municipality backed down. Later in the century, Ayurvedic medicine was recognized by the government and a training hospital called Ayurvedic Mahavidyalaya with 80 beds was established in the city.[89] The Seva sadan institute led by Ramabai Ranade was instrumental in starting training in nursing and midwifery at the Sassoon Hospital. A maternity ward was established at the KEM Hospital in 1912.[90][91] Availability of midwives and better medical facilities was not enough for high infant mortality rates. In 1921, the infant mortality rate was at a peak of 876 deaths per 1000 births.[92]

Center of social reform and nationalism[edit]

The city was an important centre of social and religious reform movements, as well as the nationalist movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Notable civil-societies founded or active in the city during the 19th century include the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, the Prarthana samaj, the Arya Mahila Samaj, and the Satya Shodhak Samaj. The Sarvajanik Sabha took an active part in relief efforts during the famine of 1875–76. The Sabha is considered the forerunner of the Indian National Congress, established in 1885.[93][94] Two of the most prominent personalities of Indian Nationalism in the late 19th and early 20th century, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who were on opposite sides of the political spectrum, called Pune their home. The city was also a centre of social reform led by Mahatma Jyotirao Phule, Justice Ranade, feminist Tarabai Shinde, Dhondo Keshav Karve, Vitthal Ramji Shinde, and Pandita Ramabai.[95] Most of the early social reform and nationalist leaders of stature in Pune were from the Brahmin caste, who belonged to the Congress party or its affiliated groups. The non-Brahmins in the city started organizing in the early 1920s, under the leadership of Keshavrao Jedhe and Baburao Javalkar. Both belonged to the Non-Brahmin party. Capturing the Ganpati and Shivaji festivals from Brahmin domination were their early goals.[96] They combined nationalism with anti-casteism as the party's aim.[97] Later on in the 1930s, Jedhe merged the non-Brahmin party with the Congress party, and transformed the party from an upper-caste dominated body to a more broadly based, but also Maratha-dominated party in Pune and other parts of Maharashtra.[98]

Mahatma Gandhi was imprisoned several times at Yerwada Central Jail. The historic Poona Pact, between B.R. Ambedkar and Gandhi on reserved seats for the untouchable castes, was signed in 1932.[99][100][101] Gandhi was placed under house arrest at the Aga Khan Palace in 1942–44, where both his wife, and aide Mahadev Desai died.

Culture[edit]

The social reformers and nationalist leaders in the city were greatly aided by the availability of printing presses. The Chitrashala press and the Aryabhushan press of Vishnu Shastri Chiplunkar, were the notable printing presses based in Pune in the 19th century.[102] The first Marathi newspapers published from the city were Mitrodaya in 1844 and Dnyanprakash in 1849. Christian missionaries based in Bombay and Pune started a journal called Dnyanodaya in the 1840s, to criticise Hindu social customs as well as to impart knowledge on secular subjects such as science and medicine. In reply to the missionary criticism, Krishna Shastri Chiplunkar and Vishnu Bhikaji Gokhale started Vicharlahari and Vartaman Dipika respectively in 1852. Later in the 19th century, Tilak and Agarkar started the English newspaper Mahratta and the Marathi paper, Kesari, respectively. These papers were printed at the Aryabhushan press.[103] After ideological differences with Tilak, Agarkar left Kesari and started his own reformist paper, Sudharak. Most of the above papers were either run by Brahmins or catered to the upper castes. The Bombay journals, Deenbandhu and Vitalwidhvansak, established in 1877 and 1886 respectively, catered to the non-Brahmin castes, and especially propagated the anti-caste philosophy of Mahatma Phule. In the early 20th century, a number of newspapers were established or had a special Pune edition. Prabhat in the 1940s, was the first one anna newspaper that catered to the lower income classes. The Sakal started by Nanasaheb Parulekar in 1931 is the most popular Marathi daily in the city to this day.[104]

The public Ganeshotsav festival, popular in many parts of India in modern times was started in Pune in 1892, by a group of young Hindu men.[105] However, it was Nationalist leader, Tilak who transformed the annual domestic festival into a large, well-organised public event.[106] Tilak recognized Ganesha's appeal as "the god for everybody",[107][108] popularising Ganesh Chaturthi as a national festival to "bridge the gap between Brahmins and 'non-Brahmins' and find a context in which to build a new grassroots unity between them", generating nationalistic fervour in the Maharashtrian people to oppose British colonial rule.[109][110][111] Until then, Hindus in Pune participated in the Shia Muslim festival of Muharram, by making donations and making the Tazia.[112] There were about 100 public Ganpatis installed in the late 1800s. This increased to about 300, at the end of British rule.[113] Encouraged by Tilak, Ganesh Chaturthi facilitated community participation when the colonial authorities, on the other hand, discouraged social and political gatherings to control unrest by the Indian population. The festival allowed public entertainment in the form of intellectual discourse, poetry recitals, plays, concerts, and folk dances.[114] In 1895, Lokmanya Tilak also took a lead in public celebration of the birthday of Shivaji, the founder of Maratha empire.[115] Justice Ranade started the spring lecture series called Vasant Vyakhyanmala in 1875.[116][117]

During the lengthy period of British rule, many different forms of entertainment became popular and subsequently faded in Pune. In the 1840s, plays based on stories from the Hindu epics such as Ramayana and Mahabharat were made popular by the traveling troupes of Vishnudas Bhave. For the next forty years, plays by the traveling troupes and performances in tents or even private dwellings were extremely popular among the Marathi speaking population of the city.[118] The Marathi musical theater of the later period was built on the foundation of the travelling theatre. Another art form popular in this era was Lavani and Tamasha, danced and performed at the Aryabhushan theater.[119] The city was a pioneer in the movie business, with companies like Prabhat studios producing quality movies. The first movie theatre in Pune was called Aryan Theatre. After the advent of talkies in the 1930s, the word (talkies) was used to denote a cinema hall. Most of the early halls had western names, such as Minerva, Globe, Liberty, etc.

The British rulers of India loved outdoor sports and built facilities for their leisure.[120] British rule in Pune saw both the introduction of British sports such as cricket, and the development of the new game of Badminton.[121] The building of a low dam at Bund gardens, financed by Parsi businessman, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy in 1860, allowed boating on the Mula-Mutha river for recreation.[122] The cantonment area of the city had a race course which still hosts horse racing. The British also built a golf course, which is still operational as the Poona Golf club in a presently sub-urban setting. There were exclusively-white clubs such as Poona Europeans, and clubs based on religion such as Poona Parsees and Poona Hindu Gymkhana, for Cricket, by the end of the 19th century. The latter club was dominated by the educated Brahmin caste of the city. However, two lower-caste brothers from the city, became stars of Indian cricket in the early 20th century. They were Palwankar Baloo and his brother, Vithal Palwankar. Vithal was appointed the captain of the Hindus in a quadrilateral cricket tournament between the Hindus, Parsis, Muslims, and Europeans.[123][124] British rule also saw a parallel development of indigenous sports at the traditional akhada or talim. However, the 1897 assassination of Rand by the Chapekar brothers, who ran a talim in Pune called Gophan, led to these venues being viewed with suspicion by the colonial authorities, for being potential centers of extremist views.[125] The committee to set rules for Kho-kho was established in the city in 1914.[126] The Deccan Gymkhana sports club formed in the early 20th century was instrumental in organizing the first Indian delegation to an Olympic meeting at Antwerp in 1920[127] The Maharashtra Mandal club formed in the early 20th century, took the lead in promoting physical culture and education. The club promoted both indigenous as well as western sports.[125][128]

Post-Independence (1947–present)[edit]

The period between 1947 and the present day saw Pune turning from a mid-size city to a large metropolis. This period saw a huge influx of people to the city due to opportunities offered by the boom in the manufacturing industry, and lately in the software field. The influx has been from other areas of Maharashtra as well as from outside the state. The Indian Government embarked on a period of economic liberalization in 1991 that had a tremendous influence on the growth of the city, and therefore the post-independence period can be divided into two periods of 1947–1991 and 1991–present.

After gaining independence from British rule in 1947, Pune became part of the Bombay state. Just after a year of independence, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in 1948. Gandhi's assassin, Nathuram Godse and most of his fellow conspirators were from Pune.[129] In 1950s, Pune came at the forefront of the struggle for a unified state of Maharashtra for the Marathi speakers. Many leaders of the Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti, such as Keshavrao Jedhe, S.M. Joshi, Shripad Amrit Dange, Nanasaheb Gore and Prahlad Keshav Atre, were based in Pune. After the spectacular success of the Samiti in Marathi speaking areas, the Congress party government at the center agreed to merge Marathi speaking areas into the newly created state of Maharashtra in 1960, with Pune as one of its leading cities.[130][131][132] The city has been part of the Pune Lok sabha constituency since independence. Since independence, the city has more often than not, elected candidates from the Congress party such as Vithalrao Gadgil, and in recent past, Suresh Kalmadi who was charged with corruption. The city elected opposition candidates in times of crisis, such as Nanasaheb Gore during the struggle for united Maharashtra in 1957, or Mohan Dharia after the lifting of Emergency in 1977. The city and its surrounding areas have six single-member constituencies for Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha. The Congress party or its breakaway factions such as NCP, have historically dominated elections to this body.

City growth and development[edit]

The population of the city grew rapidly after independence, from nearly 0.5–0.8 million in 1968 to 1. 5 million in 1976.[133] By 1996, the population had increased to 2.5 million.[134] By 2001, the population had increased to 3.76 million, making Pune one of the twenty most populous cities in India.[135] The city until the 1970s was referred to as "Pensioners' Paradise", since many government officers, civil engineers, and Army personnel preferred to settle down in Pune after their retirement[136] The status of Pune was elevated from town to city, when the Municipality was converted into Pune Mahanagar Palika or the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) in the year 1950.[137] In order to integrate planning, the Pune Metropolitan Region covering the areas under PMC, the Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal Corporation, the three cantonments, and the surrounding villages was defined in 1967.[138]

Industrial development started in the 1950s, in the outlining areas of the city such as Hadapsar, Bhosari, and Pimpri. The first big operation to set up shop was the government run Hindustan Antibiotics in Pimpri in 1954.[139] The area around Bhosari was set aside for industrial development, by the newly created MIDC in the early 1960s. MIDC provided the necessary infrastructure for new businesses to set up operations.[140] Telco (now Tata Motors) started operations in 1961, which gave a huge boost to the automobile sector. After 1970, Pune emerged as the leading engineering city of the country with Telco, Bajaj, Kinetic, Bharat Forge, Alfa Laval, Atlas Copco, Sandvik, and Thermax expanding their infrastructure. This allowed the city to compete with Chennai for the title of "Detroit of India" at that time.[141] The growth in the Pimpri Chinchwad and Bhosari areas allowed these areas to incorporate as the separate city of Pimpri-Chinchwad. In light of the rapid growth, the Pune metropolitan area was defined in 1967. It includes Pune, the three cantonment areas and numerous surrounding suburbs.[142] After the 1991 economic liberalization, Pune began to attract foreign capital, particularly in the information technology and engineering industries. During the three years before 2000, Pune saw huge development in the Information Technology sector, and IT Parks were set up in Aundh, Hinjewadi, and Nagar road[143] By 2005, Pune overtook both Mumbai and Chennai to have more than 200,000 IT professionals.[citation needed] In the year 2008, many multinational automobile companies like General Motors, Volkswagen, and Fiat, set up facilities near Pune in the Chakan and Talegaon areas.

Public transport in form of bus service, was introduced in the city just before independence using a private provider. The city took over the service after independence, as Poona Municipal transport (PMT). In the 1990s the PMT and Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal Transport (PCMT), the bus company running the service in Pimpri-Chinchwad, had a combined fleet of over a thousand buses. Several employers from the Industrial belt near Pimpri – Chinchwad and Hadapsar, also offered private bus service to their employees due to patchy municipal transport.[144] The number of buses belonging to these companies was several times more than the number of Municipal buses.[144] The two bus companies merged in 2007 to form the PMML. In 2006, the city was the first in India to develop the Bus Rapid Transit System (BRT), but due to a number of factors the project ran into delays. In 2008, the Commonwealth Youth Games took place in the city, which encouraged additional development in the north-west region of the city, and added a fleet of buses running on Compressed Natural Gas (CNG). Pune was also connected to other towns and cities in Maharashtra by Maharashtra State Transport buses that began operating in 1951.

From the 1960s onward, horse-drawn Tanga was gradually replaced by the motorized three-wheeler Autorickshaw, for intermediate public transport. Their number grew from 200 in 1960, to over 20,000 in 1996. From the 1930s, Pune was known as the cycle city of India. However, the cycle was replaced by motorized two-wheelers from the 1970s onward. For example, the number of two-wheelers increased from 5 per 1000 people, to 118 per 1000, in the period between 1965–1995.[144] In 1989, Dehu Road-Katraj bypass (Western bypass) was completed, reducing traffic congestion in the inner city but also leading to growth in Industry as well as housing along the bypass, in the decades following the opening of the road. In 1998, work on the six-lane Mumbai-Pune expressway began, and was completed in 2001. This toll-road significantly reduced the journey time between the two cities. In 1951, a number of Railway companies including GIPR, merged to form the Central Railway zone, with Pune as an important railway junction. The pace of laying down new rail tracks had been slow in the initial post-independence era. Nevertheless, one of the major infrastructure project in this period was conversion of the Pune-Miraj railway from metre gauge to the wider broad-gauge in 1972.

Pune has been an important base for armed forces. The airport established by the British at Lohgaon in 1939, was further developed by the Indian Air Force. The airport was used for domestic short-haul passenger flights until 2005, when the airport was upgraded to international airport with flights to Dubai, Singapore, and Frankfurt.[145][146] In 2004–05, Pune Airport handled about 165 passengers a day. It increased to 250 passengers a day in 2005–06. There was a sharp rise in 2006–07, when daily passengers reached to 4,309. In 2010– 2011, the passenger number hit about 8,000 a day.[147]

In 1961, the Panshet Dam which was then under construction, failed. The breach released a tremendous volume of water, which also damaged the downstream dam of Khadakwasla. The resulting flood damaged or destroyed a lot of old housing near the river bank, in the Narayan, Shaniwar, and Kasba Peth areas of the city.[148][149] The damaged dams were repaired and continue to provide water to the city. The rapid rise in the city population in the last few decades, meant that the sewage treatment plants in 2008 were treating just over half of the sewage and discharging the rest in the local Mutha and Mula rivers, that severely polluted these rivers.[citation needed]

The rapid industrialization led to a huge influx of new people to the city, with housing supply not keeping pace with demand, and therefore there was a great increase in slum dwellings in this period.[150] In the post-Panshet period, new housing was mainly in the form of bungalows and apartment buildings. In the 1980s, however, due to heavy demand for housing, there was a trend towards knocking down bungalows and converting them into apartment buildings, with a consequent increase in population density and increased demand for utilities such as water supply.[151] Since the 1990s, a number of landmark integrated townships[152] have come into being in the city, such as Magarpatta, Nanded, Amanora, Blue Ridge, Life Republic, and Lavasa. Most of these were built by private developers and also managed privately.

In 1949, University of Poona was established with 18 affiliated colleges in 13 districts of Bombay state surrounding Pune.[153] The creation of the university was opposed by some groups that had been running the long established colleges in the city.[154] The post-independence period also saw the establishment of the National Defence Academy at Khadakwasla, Film and Television Institute of India at the former Prabhat studios in 1960,[155] and National Chemical Laboratory at Pashan. Pune was also made the headquarters of the Southern Command of the Indian Army.[156] Many private colleges and universities were set up in the city during the years after the State Government under chief minister Vasantdada Patil liberalised the Education Sector in 1982.[157] Politicians and leaders involved in the huge cooperative movement in Maharashtra were instrumental in setting up the private institutes.[158]

Culture[edit]

A number of newspapers from the British era, continued publishing decades after independence. These included Kesari, Tarun Bharat, Prabhat, and Sakal. After independence, Kesari took a more pro-Congress party stance, whereas Tarun Bharat was sympathetic towards Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Jan sangh and its successor, the BJP. Under the leadership of Nanasaheb Parulekar, Sakal maintained a politically-neutral stand.[159] It was the most popular Marathi daily during Parulekar's stewardship, and has maintained that position since the 1980s, under the control of Pawar family.[160][161] Presently, Kesari is only published as an online newspaper. Mumbai-based Maharashtra times, Loksatta, and Lokmat, introduced their Pune editions in the last fifteen years. The Mumbai-based popular English newspaper, Indian express has a Pune edition. Its rival, the Times of India introduced a tabloid called Pune Mirror in 2008.

The government-owned All India radio (AIR) established a station in Pune in October 1953.[162][163] One of the early notable programs produced by the station was Geet Ramayan, a series of 55 songs created by the poet Ga Di Madgulkar and composer Sudhir Phadke in 1955[164] AIR Doordarshan service started relaying black and white television signals, from Bombay TV-station to Pune in 1973. A relay station was built at the fort of Sinhagad to receive signals. Color service was introduced to Pune and rest of India during the 1982 Asian Games.

Since the British era, live theater in form of musical drama had been popular in Pune and other Marathi speaking areas. In the post-independence era, theater became a minor pursuit, and the genre of musical-drama declined due to cost. Despite lower attendance, the post-independence era saw the building of many new drama theaters by the Pune Municipal corporation, such as the Bal Gandharva Ranga Mandir in the 1960s, and Yashwantrao Chavan Natya Gruha in the 1990s.[165] Theater companies such as Theatre academy, flourished in the 1970s with plays such as Ghashiram Kotwal and Mahanirvan.[166][167] The popular entertainment for masses in Pune and in urban India, in the post-independence era was cinema. Theaters showing single-films were dotted around the old city. The early theaters used to be quite basic with regard to comfort and technology. In the 1970s, new theaters were built that were fully air-conditioned, with some of them such as Rahul Theater, having a wide-format screen for showing 70 mm films. The theaters used to show mostly Hindi films, and a few Marathi and English ones. The post-1991 liberalization period saw the rise of multiplex cinemas and decline of the old theaters.

For a city of its size, Pune always had very few public parks. The Bund Garden and the Empress Gardens were developed during the British era, in the Cantonment area. In the post-independence era, the Peshwe Park and Zoo was developed in 1953, by the Municipal corporation, close to Parvati hill, at the same location where Sawai Madhavrao had his own collection of animals.[168] The Peshwa-era lake, next to the park with a Ganesh temple, was drained and turned into a garden in the 1960s and named Saras Baug. The Parvati and Taljai hills behind it, were turned into a protected nature reserve called Pachgaon hill in the 1980s. The reserve contains area under forest, and is a stop for migratory birds.[169][170]

Maharashtra Cricket Association was formed in the 1930s, and has been based in Pune since then. In 1969, the headquarters of the association was moved to 25,000 capacity Nehru stadium. With the introduction of the limited-over game and low capacity of the stadium, the association built a new and larger capacity stadium on the outer fringes of the city. In the 1970s, the Chhatrapati Shivaji Stadium was built in the Mangalwar Peth area of the city, to host Kusti and other traditional Indian sports.[171] The 1994 National games were hosted by the city. A new sports venue called Shree Shiv Chhatrapati Sports Complex was built at Balewadi for this purpose. The complex was also used for 2008 Commonwealth youth games.

Maharashtrian Hindu society until the early 20th century, was fairly conservative with regard to food and there were few conventional restaurants in Pune. The early restaurants in the city, mainly in the cantonment area, were established by Parsis and Iranians. Lucky and Cafe Good Luck were the first Irani restaurants in the Deccan Gymkhana area, near the Ferguson College. For many young men from orthodox-Hindu vegetarian families, ordering an omelette at these restaurants was considered quite daring.[172][173] The first family restaurant in Deccan Gymkhana area, Cafe Unique, was started by a Mr. Bhave in the 1930s.[174] In the post-independence era, a number of restaurants were established by immigrants from the coastal Udupi district in Karnataka. These establishments offered a simple South Indian meal of dosa and idlis. The early post-independence era also saw opening of the iconic Chitale Bandhu sweet shops, that offered Maharashtrian sweet and savory snacks.[175] After the 1991 market liberalization, the city became more cosmopolitan, and several American franchise-restaurants, such as McDonald's,[176] Domino's, etc. were established.[177]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Gadgil and the Gazetteer of Bombay state that Baria Arab was from the Khaljis whereas Kantak says he was with the successor rulers, the Tughlaqs

- ^ Per, M.R. Kantak, ass-drawn plough was used by a victor as symbolic gesture of destruction and also to curse the place[3]

- ^ Building cantonments was a peculiarly British phenomenon in the Indian subcontinent. Whenever the British occupied new territory, they built new garrison towns near the old cities and called them cantonments.[citation needed]

Bibliography[edit]

- L. W. Shakespear (1916). Local History Of Poona: And its Battlefields. Macmillan, London.

- Rao Bahadur Dattatraya Balvanta Parasnis (1921). Poona in Bygone Days. Times Press, Bombay.

- The Poona guide and directory. F. S. Jehangir, Poona. 1922.

- Naregal, Veena (2002). Language politics, elites, and the public sphere: western India under colonialism. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1843310549.

- Maharashtra Government Gazetteer -[178]

- Joseph Maguire, Sport across Asia: politics, cultures and identities[125]

- Gadgil, DR, Housing in Poona[179]

- Mridula Ramanna, Western medicine and public health in colonial Bombay, 1845–1895[180]

- Ashutosh Joshi, Town Planning: Regeneration of Cities (2008) [181]

- Meera Kosambi , Rao, Bhat, Kadekar, Reader In Urban Sociology, 1991[182]

- Ratna N. Rao, Social Organization in an Indian Slum (Study of a Caste Slum), 1990[183]

- Khairkar, V.P. 2008. Segregation of Migrants Groups in Pune City, India[184]

- Sidhwani, Pranav, Spatial inequalities in big Indian Cities [185]

- Mullen, W.T., 2001. Deccan Queen: A Spatial Analysis of Poona in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries[186]

- Munshi, T., Joshi, R. and Adhvaryu, B., 2015, Land Use–transport Integration for Sustainable Urbanism[187]

References[edit]

- ^ Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind. "The Religious Complex in Eighteenth-Century Poona." Journal of the American Oriental Society 105, no. 4 (1985): 719-24. Accessed July 30, 2021. doi:10.2307/602730.|page=719|quote=Shivaji spent his childhood in pune with his mother jijabai and mentor Dadoji Kondeo where the family was housed in an unpretentious house.

- ^ "Shaniwarwada was centre of Indian politics: Ninad Bedekar". Daily News and Analysis. 29 November 2011. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Kantak, M. R. (1991–1992). "Urbanization of Pune: How Its Ground Was Prepared". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 51/52: 489–495. JSTOR 42930432.

- ^ Gautam Sengupta; Sharmi Chakraborty; B.C. Deotare, Sushma Deo, P.P. Joglekar, Savita Joglekar, S.N. Rajguru (2008). "3, Early historic sites in Western India". The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia. New Delhi, India: Pragati Publications in association with Centre for Archaeological Studies and Training. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-316-41898-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ JOGLEKAR, P. P., et al. “A NEW LOOK AT ANCIENT PUNE THROUGH SALVAGE ARCHAEOLOGY (2004-2006).” Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, vol. 66/67, 2006, pp. 211–25. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42931448 Archived 6 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 6 Jun. 2022.

- ^ Gadgil, D. R. (1945). Poona A Socio-Economic Survey Part I. Pune, India: Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics. p. 13. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Government, of Bombay Presidency (1885). Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona, Volume XVIII part III. Bombay: Government central press. p. 403. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Joseph G. Da Cunha (1900). Origin of Bombay. Bombay, Society's library; [etc., etc.]

- ^ a b Gadgil, D.R., 1945. Poona a socio-economic survey part I. Economics.

- ^ "Monuments in Pune". Pune district administration. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ "Punediary". Punediary. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Duff, J.G., 1990. History of the Marathas, Vol. I. Cf. MSG, p. 437.

- ^ Jaswant Lal Mehta (1 January 2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707-1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Archived from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Kosambi, Meera (1989). "Glory of Peshwa Pune". Economic and Political Weekly. 24 (5): 247.

- ^ a b Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1985). "The Religious Complex in Eighteenth-Century Poona". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 105 (4): 719–724. doi:10.2307/602730. JSTOR 602730.

- ^ Gadgil, D.R., 1945. Poona a socio-economic survey part I. Economics. page 14.

- ^ Nilekani, Harish Damodaran (2008). India's new capitalists: caste, business, and industry in a modern nation. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 50. ISBN 978-0230205079. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Dikshit, M. G. (1946). "Early Life of Peshwa Savai Madhavrao (Ii)". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 7 (1/4): 225–248. JSTOR 42929386.

- ^ Review: Glory of Peshwa Pune Reviewed Work: Poona in the Eighteenth Century: An Urban History by Balkrishna Govind Gokhale Review by: Meera Kosambi Economic and Political Weekly Vol. 24, No. 5 (4 February 1989), pp. 247–250

- ^ Khare, K. C., and M. S. Jadhav. "Water Quality Assessment of Katraj Lake, Pune (Maharashtra, India): A Case Study. " Proceedings of Taal2007: The 12th World Lake Conference. Vol. 292. 2008.

- ^ Peshwas diaries Volume VIII. p. 354.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (2013). War, culture and society in early modern South Asia, 1740–1849. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-0415728362. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Feldhaus, Anne, ed. (1998). Images of women in Maharashtrian society: [papers presented at the 4th International Conference on Maharashtra: Culture and Society held in April, 1991 at the Arizona State University]. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press. p. 15 51. ISBN 978-0791436608. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ India. Police Commission and India. Home Dept, 1913. History of Police Organization in India and Indian Village Police: Being Select Chapters of the Report of the Indian Police Commission, 1902–1903. University of Calcutta.

- ^ Jayapalan, N. (2000). Social and cultural history of India since 1556. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 55. ISBN 9788171568260. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Preston, Laurence W. "Shrines and neighbourhood in early nineteenth-century Pune, India. " Journal of Historical Geography 28. 2 (2002): 203–215.

- ^ Kumar, Ravinder (2004). Western India in the Nineteenth century (Repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-0415330480. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Adachi, K., 2001. "Dakshina Rules of Bombay Presidency (1836–1851)" Archived 21 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Minamiajiakenkyu, 2001(13), pp. 24–51.

- ^ Kyosuke Adachi, "Dakshina Rules of Bombay Presidency (183(−1851): Its Constitution and Principles", Journal of the Japanese Association for South Asian Studies, 13, 2001

- ^ Kosambi, Meera (1989). "Glory of Peshwa Pune". Economic and Political Weekly. 248 (5): 247.

- ^ "Shaniwarwada was centre of Indian politics: Ninad Bedekar – Mumbai – DNA". Dnaindia.com. 29 November 2011. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Rao Bahadur Dattatraya Balvanta Parasnis (1921). Poona in Bygone Days. Times Press, Bombay.

- ^ Maguire, Joseph (2011). Sport across Asia: politics, cultures and identities 7 (1. publ. ed.). New York and UK: Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 978-0415884389. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "2. Representing Maratha Power". Creative Pasts: Historical Memory and Identity in Western India, 1700-1960, New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, 2007, pp. 40-70. https://doi.org/10.7312/desh12486-003The capital, Pune, grew into a prosperous city in this period, and not surprisingly, there are several powadas in celebration of this prosperity. A composition by Ram Joshi is particularly vivid.

- ^ Rege, S., 1995. The hegemonic appropriation of sexuality: The case of the lavani performers of Maharashtra. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 29(1), pp. 25–37. http://sharmilarege.com/resources/Hegemonic%20Appropriation%20of%20Sexuality_Rege.pdf Archived 23 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cashman, Richard I. (1975). The myth of the Lokamanya: Tilak and mass politics in Maharashtra. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0520024076.

peshwa dance.

- ^ Shirgaonkar, Varsha; Ramakrishnan, K S (2015). "Lavani Literature As a Source of Socio-Cultural History of Medieval Maharashtra". International Journal of Humanities, Arts, Medicine and Sciences. 3 (6): 41–48.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher (2000). Queen Victoria: A Personal History. Harper Collins. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-00-638843-2.

- ^ "Moledina, M.H., 1953. History of the Poona Cantonment, 1818–1953" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Kadekar, LN (1991). A Reader in urban sociology. London: Sangam. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0863111518.

- ^ History of Foundation Archived 12 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gadgil, D. R. (1945). Poona A Socio-Economic Survey Part I. Pune, India: Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics. p. 22.

- ^ Mehta, Surinder K (1968): "Patterns of Residence in Poona (India) by Income, Education, and Occupation (1937–65), " American Journal of Sociology, pp 496–508.

- ^ Nathan Katz (18 November 2000). Who Are the Jews of India?. University of California Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-520-92072-9.

- ^ Cashman, Richard I. (1975). The myth of the Lokamanya: Tilak and mass politics in Maharashtra. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 20. ISBN 978-0520024076.

- ^ Keer, Dhananjay (1997). Mahatma Jotirao Phooley: father of the Indian social revolution ([New ed.]. ed.). Bombay: Popular Prakashan. p. 143. ISBN 978-81-7154-066-2. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Wheeler, M., 1960. The Cambridge History of India. CUP Archive.

- ^ Chhabra, G. S. (2004). Advanced study in the history of modern India ([3rd ed.] ed.). New Delhi: Lotus Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-8189093075. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Jaffe, James (2015). Ironies of Colonial Governance: Law, Custom and Justice in Colonial India. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University press. pp. 68–96. ISBN 978-1107087927. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Wadia, Sorab P. N. (1897). The institution of trial by jury in India. University of Michigan. pp. 29–30.

jury poona.

- ^ Rao, Ratna N. (1990). Social organisation in an Indian slum: study of a caste slum (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Mittal Publications. p. 21. ISBN 9788170991861. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ McGowan, Abigail (2009). Crafting the nation in colonial India (1st ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-230-62323-1. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Gadgil, D. R. (1945). Poona A Socio-Economic Survey Part I. Pune, India: Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics. pp. 101–151. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Chapman, James (2003). Cinemas of the world: film and society from 1895 to the present. London: Reaktion. p. 327. ISBN 978-1-86189-162-4. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Shankar, V.K. and Sahni, R., 2012, November. Chinese Goods for Indian Gods. In Symposium on India-China Studies held at the University of Delhi (New Delhi) during (Vol. 2, p. 3).

- ^ Dastane, Sarang (6 October 2010). "Mahatma Phule Mandai completes 125 years". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Heitzman, James (2008). The city in South Asia (1st ed.). London: Routledge. p. 125. ISBN 978-0415574266.

pune.

- ^ Gazetteer of The Bombay Presidency: Poona (Part 2). Government Central press. 1885. p. 156. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona (2 PTS.)". 1885. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Chronology of railways in India, Part 2 (1870–1899). "IR History: Early Days – II". IFCA. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kerr, Ian J. (2006). Engines of change: the railroads that made India. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 128. ISBN 978-0275985646.

- ^ "History of PMPML Undertaking". Pune Mahanagar Parivahan Mahamandal Ltd. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Gadgil, D. R. (1945). Poona A Socio-Economic Survey Part I. Pune, India: Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics. pp. 240–244.

- ^ Gorman, M., 1971. Sir William O'Shaughnessy, Lord Dalhousie, and the Establishment of the Telegraph System in India. Technology and Culture, 12(4), pp. 581–601.

- ^ Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Poona (2 pts.). Vol. XVIII. Bombay: Government Central Press. 1885. pp. 162–163.

- ^ Gazetteer of The Bombay Presidency: Poona (Part 2). Government Central press. 1885. pp. 16–18.

- ^ Harrison, Mark (1994). Public health in British India: Anglo-Indian preventive medicine 1859–1914. Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0521441278.

- ^ Sumit Roy, Sumit. "Investigations into the Process of Innovation in the Indian Automotive Component Manufacturers with Reference to Pune as a Dynamic City-Region" (PDF). myweb. rollins.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Narayan, Shiv (1935). Hydroelectric Plants India. Pune, India. p. 64.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Anglican Scholastic Heritage in Poona 1818–1947", Research Article, Historicity Research Journal Volume 2 | Issue 9 | May 2016 Pramila Dasture

- ^ Naregal, Veena (2002). Language politics, elites, and the public sphere: western India under colonialism. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1843310549.

- ^ Cashman, Richard I. (1975). The myth of the Lokamanya: Tilak and mass politics in Maharashtra. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0520024076.

fergusson college.

- ^ Keer, Dhananjay (1997). Mahatma Jotirao Phooley: father of the Indian social revolution ([New ed.]. ed.). Bombay: Popular Prakashan. p. 24. ISBN 978-81-7154-066-2.

- ^ Ghurye, G. S. (1954). Social Change in Maharashtra, II. Sociological Bulletin, page 51.

- ^ Forbes, Geraldine (1999). Women in modern India (1. pbk. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780521653770.

- ^ Henry Herbert Dodwell (1929). The Cambridge History of the British Empire. CUP Archive

- ^ A. A. Ghatol, S. S. Kaptan, A. A. Ghatol, K. K. Dhote (1 January 2004). Industry Institute Interaction. Sarup & Sons. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-81-7625-486-1.

- ^ The Asiatic annual register; or, A view of the history of Hindustan,: and of the politics, commerce, and literature of Asia, ... Printed for J. Debrett, Piccadilly, by Andrew Wilson, the Asiatic Press, Wild Court. 1859. pp. 74–.

- ^ Paulo B. Lourenço (February 2006). Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Structural Analysis of Historical Constructions: Possibilities of numerical and experimental techniques. Macmillan India. pp. 1811–1813. ISBN 978-1-4039-3157-3.

- ^ Suresh Kant Sharma (2005). Encyclopaedia of Higher Education: Scientific and technical education. Mittal Publications. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-81-8324-017-8.

- ^ The Asiatic annual register; or, A view of the history of Hindustan,: and of the politics, commerce, and literature of Asia, ... Printed for J. Debrett, Piccadilly, by Andrew Wilson, the Asiatic Press, Wild Court. 1859. pp. 77–.

- ^ McGowan, Abigail (2009). Crafting the nation in colonial India (1st ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-230-62323-1.

- ^ Mutalik, Maitreyee. "Review of Body Snatching to Body Donation: Past and Present: A Comprehensive Update., Int J Pharm Bio Sci 2015 July; 6(3): (B) 428 – 439"

- ^ Chopra, Preeti (2011). A joint enterprise: Indian elites and the making of British Bombay. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0816670369.

- ^ Arnold, David (2002). Science, technology and medicine in Colonial India (Repr. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 142–146. ISBN 9780521563192.

- ^ Arnold, David (1988). Imperial medicine and indigenous societies. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0719024955.

- ^ Ramanna, Mridula (2012). Health care in Bombay Presidency, 1896–1930. Delhi: Primus Books. pp. 19–21. ISBN 9789380607245.

- ^ Harrison, Mark (1994). Public health in British India: Anglo-Indian preventive medicine 1859–1914. Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0521441278.

- ^ Ramanna, Mridula (2012). Health care in Bombay Presidency, 1896–1930. Delhi: Primus Books. p. 176. ISBN 9789380607245.

- ^ Ramanna, Mridula (2012). Health care in Bombay Presidency, 1896–1930. Delhi: Primus Books. p. 102. ISBN 9789380607245.

- ^ Kosambi, Meera; Feldhaus, Ann (2000). Intersections: socio-cultural trends in Maharashtra. New Delhi: Orient Longman. p. 139. ISBN 9788125018780.

- ^ Ramanna, Mridula (2012). Health care in Bombay Presidency, 1896–1930. Delhi: Primus Books. p. 110. ISBN 9789380607245.

- ^ Johnson, Gordon (1973). Provincial Politics and Indian nationalism: Bombay and the Indian National Congress, 1880 – 1915. Cambridge: Univ. Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0521202596.

- ^ Roy, Ramashray, ed. (2007). India's 2004 elections: grass-roots and national perspectives (1. publ. ed.). New Delhi [u.a.]: Sage. p. 87. ISBN 9780761935162.

- ^ Ramachandra Guha, "The Other Liberal Light, " New Republic 22 June 2012 Archived 4 February 2013 at archive.today

- ^ Hansen, Thomas Blom (2002). Wages of violence: naming and identity in postcolonial Bombay. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0691088402. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Jayapalan, N. (2000). Social and cultural history of India since 1556. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 162. ISBN 9788171568260. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Omvedt, Gail (1974). "Non-Brahmans and Nationalists in Poona". Economic and Political Weekly. 9 (6/8): 201–219. JSTOR 4363419.

- ^ "Poona Pact – 1932". Britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ "AMBEDKAR VS GANDHI: A Part That Parted". OUTLOOK. 20 August 2012. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "Museum to showcase Poona Pact". The Times of India. 25 September 2007. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

Read 8th Paragraph

- ^ Pinney, Christopher (2004). Photos of the gods: the printed image and political struggle in India. London: Reaktion. pp. 47–50. ISBN 978-1861891846.

- ^ Chandra, Shefali (2012). The sexual life of English: caste and desire in modern India. Durham: Duke Univ. Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0822352273. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Prabhu, M.P., History of Press in Maharashtra. SHODH PRERAK, pp. 291–295.

- ^ Kaur, R. (2003). Performative politics and the cultures of Hinduism: Public uses of religion in western India. Anthem Press. pp. 38–48. ISBN 9781843311386. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara Daly; Metcalf, Thomas R. (26 November 2001). A Concise History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-521-63027-6.

- ^ Momin, A. R., The Legacy Of G. S. Ghurye: A Centennial Festschrift, p. 95.

- ^ For Ganesha's appeal as "the god for everyman" as a motivation for Tilak, see: Brown (1991), p. 9.

- ^ Brown, Robert L. (1991). Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God. Albany: State University of New York. ISBN 978-0-7914-0657-1.Brown (1991), p. 9.

- ^ For Tilak's role in converting the private family festivals to a public event in support of Indian nationalism, see: Thapan, p. 225. Thapan, Anita Raina (1997). Understanding Gaņapati: Insights into the Dynamics of a Cult. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7304-195-2.

- ^ For Tilak as the first to use large public images in maṇḍapas (pavilions or tents) see: Thapan, p. 225. Thapan, Anita Raina (1997). Understanding Gaņapati: Insights into the Dynamics of a Cult. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7304-195-2.

- ^ MICHAEL, S. M. (1986). "The politicization of the Ganaati festival". Social Compass. 33 (2–3): 185–197. doi:10.1177/003776868603300205. S2CID 143986762.

- ^ Kaur, R. (2003). Performative politics and the cultures of Hinduism: Public uses of religion in western India. Anthem Press, page 60.

- ^ Cashman, Richard I. (1975). The Myth of the Lokamanya: Tilak and Mass Politics in Maharashtra. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California press. pp. 79. ISBN 978-0-520-02407-6.

ganesh chaturthi.

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A. (1989). Tilak and Gokhale: revolution and reform in the making of modern India (1. publ. in Oxford India pbk. ed.). Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780195623925. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "Vasant Vyakhyanmala to start from April 21". No. 19 April 2011. sakal news papers. sakaltimes. 19 April 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ "Month-long spring lecture series that has been a tradition for centuries in Pune will be held till May 20". dna. dna. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ Kulkarni, K.A., 2015. The Popular Itinerant Theatre of Maharashtra, 1843–1880. Asian Theatre Journal, 32(1), pp. 190–227.

- ^ Alison, Arnold; Booth, Gregory D. (2000). The Garland encyclopedia of world music. New York [u.a.]: Garland. p. 424. ISBN 9780824049461. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Winchester, Simon; Morris, Jan (2004). Stones of empire: the buildings of the Raj (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0192805966. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Tennyson, C., 1959. They taught the world to play. Victorian Studies, 2(3), pp. 211–222.

- ^ Kincaid, Charles Augustus; Parasnis, Rao Bahadur Dattatraya Balavant (1918). History of the Maratha People Volume 1 (2010 ed.). London: Oxford University press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1176681996. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Menon, Dilip M. (2006). Cultural history of modern India. New Delhi: Social Science Press. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-8187358251. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Mills, James H.; Sen, Satadru (2004). Confronting the body: the politics of physicality in colonial and post-colonial India. London: Anthem Press. pp. 129, 141. ISBN 978-1843310334. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Maguire, Joseph (2011). Sport across asia: politics, cultures and identities 7 (1 ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415884389. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Mahesh, D., 2015. A Comparative Study of Physical Fitness Among Kho-Kho and Kabaddi Male Players. International Journal, 3(7), pp. 1594–1597.[1] Archived 10 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jackson, Steven (2008). Social and cultural diversity in a sporting world (1st ed.). Bingley, UK: Emerald. pp. 172–175. ISBN 9780762314560. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Mills, James H.; Sen, Satadru (2004). Confronting the body: the politics of physicality in colonial and post-colonial India. London: Anthem Press. pp. 128–136. ISBN 978-1843310334. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ An-Naʻim, Abdullahi A., ed. (1995). Human rights and religious values: an uneasy relationship?. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi. p. 124. ISBN 9789051837773. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.