Rickie Lee Jones was just three years old when she made her debut as a performer, appearing briefly as a snowflake in a ballet recital of Bambi. “I heard the audience’s applause and took it personally,” she writes in Last Chance Texaco, a vivid memoir that traces the arc of her often turbulent life from unsettled childhood to uneasy fame. “I remained bowing long after the other snowflakes had melted and left the stage. The dance teacher had to escort me off, but the audience was delighted and the die was cast. I liked it up there.”

The stage, she tells me a lifetime later, “is where I belong. On stage, I’m whole.” On a good night, this is indeed the case, her voice moving effortlessly from the joyous to the seductive as she communes with the spirits. “I feel the invisible world,” she says, “It’s all around me, but I can’t translate it into words. Music comes close, but it’s really some other place that I know is here but I can’t fully express.”

An outsider by temperament, Jones has long walked to her own slightly off-kilter rhythm. In 1979, when she gatecrashed the mainstream with her self-titled debut album and the buoyant, jazz-tinged hit single, Chuck E’s in Love, her sudden celebrity left her feeling all at sea. “That was the biggest test,” she says, “For someone who always felt on the outside to suddenly have everyone treat me like I was above them, that was really hard. It was difficult to know how to be a person when that was going on.”

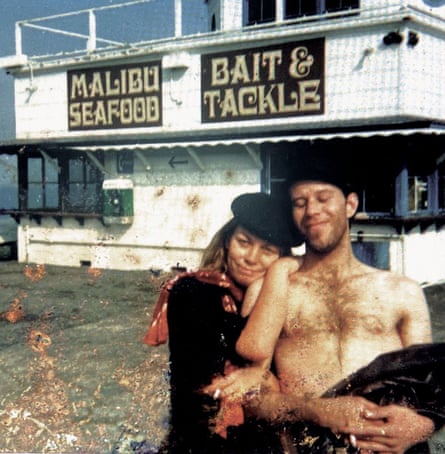

Back then, she was marketed as a boho songstress in a beret. A brief but intense relationship with Tom Waits, whose creative sensibility fleetingly chimed with her own, added to her cachet of cool. As a couple, they seemed to have emerged fully formed out of their own creative imaginations. If Waits’s stumblebum persona relied to a degree on creative method acting, she was the real deal: a survivor who had, as she puts it in the prologue of Last Chance Texaco, “lived volumes as a young girl long before I was famous”.

The book’s title comes from one of her songs, but she also chose it, she writes, “because I spent most of my life in cars, vans, and buses”. Her childhood was marked by upheaval, her parents moving from Chicago, where she was born and where her mother hailed from, to Arizona and back again, her father disappearing from time to time. In her teens, she too took to the road, her fractured childhood playing out in recklessness and risk-taking. Until relatively recently, she tells me, she found it hard to put down roots anywhere. “For a long time, my solution to any problem, big or small, was to jump in the car and drive away from it. It took me a while to learn that you really don’t solve anything that way.”

Now, aged 66, she has finally settled in New Orleans, an easy-going, music-haunted city that suits her temperament. “I’ve been here seven years, which is a kind of a record,” she says, laughing. “I think it’s a good town for me. It’s still a bit weird. There’s lots of music and not so much celebrity. I guess I’ll stay here for a while if it doesn’t get washed away in the flood.” When I ask how she has coped with lockdown, she tells me she has “air con, hot water and soft beds so what is there to complain about?” She remains a slightly eccentric free spirit, as evinced by a recent online performance she gave from her living room, resplendent in a pink polka dot dress, the wall behind her filled with vintage family portraits, candles flickering on the baby grand in the background. Set to her minimalist acoustic guitar stylings, her songs were punctuated with anecdotes and memories from a life lived to the full and with often reckless abandon. Last Chance Texaco returns to that past in often arresting detail. How difficult was it to revisit her younger, wilder life?

“Well, I wrote it over many years so the pain was spread out, but some parts were extremely tough,” she says, sighing. “Writing about the Tom Waits thing was very hard. It seemed to be an open wound that had never healed. When I first started writing about it there was still so much anger and tears that, at one point, I thought: how am I going to write about this without it just bleeding on to the paper?”

Though in the past she has been reluctant to talk about Waits, she evokes the intensity of their romance and its aftermath in some detail in her memoir. “I just kept writing it,” she tells me, “and finally a miracle happened – in telling the story over and over again, the wound healed. Now, I don’t think it would faze me any more than anyone else’s story about the night they broke up with somebody.”

Jones was born in 1954 in working-class Chicago, where her mother, Bettye, hailed from. Bettye, an abiding presence in the book, was taken into care as a child and raised in state institutions after her father was jailed for stealing chickens. She added the “e” to the end of her first name on her release, aged 16, to symbolise a new beginning, but, as Jones writes: “No matter what my mum did, she found traces of her past obstructing her future.”

In Chicago, she met Richard Loris Jones, a struggling musician whose father was a vaudeville entertainer who went by the name of Frank “Peg Leg” Jones, his fame exacerbated by his violent streak. Survivors both, the couple moved from state to state during Rickie’s childhood. “What were they running from?” she writes. “From cities, houses, and eventually, themselves, but they never got away from their difficult childhoods or their love for each other.”

If Last Chance Texaco is haunted by the long shadows of the past, it is also a story of forgiveness and acceptance. “One of the things I wanted to say is that family relations are always complex,” says Jones, “and that nobody is the bad guy. Parents can do a bad job over here and be triumphant and wonderful over there. That’s just how it is. In the end, everybody’s on their own anyway.”

For all its uncertainty, her childhood was often magical. When she was four, the family settled for a time in the then quiet town of Phoenix, Arizona, where she roamed freely in the desert, rode horses, and had adventures with her imaginary friends. She recalls that gilded time in prose that is often luminously descriptive. “I wanted,” she tells me, “to capture the rapt concentration of a child trying to catch a bug or a bird so that I could take the readers back there with me to a place where time went by so differently.”

As a young girl, music was a conduit to another world of possibility. She saved up her pocket money to buy the soundtrack of West Side Story, whose street-opera dynamics would later find their way into her songs. When she sang songs from the album to herself as she played on the street, other children, and sometimes adults, would stop to listen. “I drew a crowd!” she writes. “Music had built an accidental bridge between me and the world.”

The invisible world, as Jones calls it, made its presence felt dramatically when, aged seven, she had a premonition that something seismic was about to happen to her brother, Danny. A few weeks later, her mother received a call from the local hospital: Danny had been hit by a car while riding his motorbike and was in a critical condition. He survived, but only just, losing a leg and emerging from a coma with permanent brain impairment. “My ‘normal’ ended with the phone call,” she writes, evoking the guilt she felt for foretelling, but being unable to prevent, the tragedy. Her family fractured in the aftermath, her parents unable, as she puts it, “to find the thread to pick up and start over again”.

Her older sister, Janet, is an almost ghostly presence in the book, her troubled teenage years echoing her mother’s past. Labelled a “problem child” because of her rebelliousness, she was taken from her parents and placed in the Good Shepherd Care Home for Girls, from which she escaped more than once, eventually living as a fugitive from the law. “Childhood traumas,” Jones writes, “leave their dirty footprints on the fresh white snow of our ‘happy every afters’.”

What, I ask, became of Janet? “She passed away a few years ago,” she says, quietly. “She had a hard life, one awful thing after another, drug use, addiction. There was a little part of her that was a deer in the headlights, so tender and vulnerable, and I’d see it. But right behind that was a wave of chaos.” She pauses for a moment. “Janet was incredibly smart, but she didn’t ever figure out how to be kind. She had an acute intelligence that would aim to do harm, so I just stayed as far from her as I possibly could. It was sad, but that’s how it had to be.”

Jones describes her own teenage adventuring as “a little bit Oz, a little bit Huck Finn”. That barely does it justice. Aged 14, she lived in a cave as part of a commune, hitchhiked on her own from Big Sur to Detroit when not much older, and risked a lifetime in jail driving to Mexico and back with hippy outlaw dope smugglers. “There were definitely moments writing the book,” she says, laughing, “when I was thinking, ‘How could I have done all those things?’ But I did. Kids are wily.”

Nevertheless, there were times when she sailed too close to the wind, winding up in jail more than once, usually on suspicion of being an underage runaway with a false ID – which she was. On the Canadian border, she was arrested for “being in danger of leading a lewd and lascivious life” – she was braless under her T-shirt. She recalls several tearful calls to her parents, who, more often than not, travelled vast distances to take her home. While living in Mexico with a boyfriend, she was abducted by a rogue cab driver who drove her into the jungle intending to rape and possibly kill her. She was saved by the sudden appearance of a bus load of Federales. “There were some bad things that cast a long shadow that made them really hard to write about,” she says. “They seemed to have living darkness about them that made me feel really frightened all over again.”

For all that, I say, she seems to have had a guardian angel watching over her. “I thought about that a lot when I was writing the book. At times, it was as if someone was saying to me: ‘We have a place we want you to go and you’ll get there all right in the end after all these adventures.’” Did writing the book help her understand her younger, wilder self? “In a way, yes. Looking back, I think I was in some way running towards the safe house I would eventually find and a future that I was making happen by creating these adventures that we are now talking about. Some higher part of me was saying, it will be interesting and you won’t die.”

Throughout it all, she says, she never lost her sense of being destined for greater things. “Even as a child, I always thought I would be somebody – a singer, an actor, a dancer, maybe even a great swimmer. I never ever thought I would have a day job. It would always be a life of my own design, so I had this sense of purpose, I guess.”

Jones eventually gravitated to Venice Beach in California, working menial jobs and singing in local bands to pay the rent. It was there in 1976 that she began writing her own songs, the likes of Easy Money and Weasel and the White Boys Cool, peopling them with characters based on the maverick souls she had met along the way. She first encountered Waits at the Troubadour in Los Angeles in 1977, where he watched from the shadows as she sang a handful of songs to a near-empty club. Soon afterwards, they had a one-night stand that ended abruptly with Waits cold-shouldering her the following morning. “I was still standing on the step when he closed the door and walked away,” she writes. “The sun was up and it was already too hot. I was wearing high heels. I wanted to hide in a bush. I may have hidden in a bush.”

A few months later, she signed to Warner Brothers and, as she puts it, “things started warming up again with Tom Waits”. Their romance was all-consuming. “We fed a craving so sharp that we wanted to become each other,” she writes. It lasted barely a year, and his departure left her devastated just as her sudden celebrity swept her along in its tidal sway. In his absence, she drifted into the orbit of other wayward creative mavericks, including the supremely gifted songwriter and guitarist Lowell George, lead singer of Little Feat.

“It’s hard to say what he was really like, because I never knew him when he was not on cocaine,” she says. “He was out there all night long taking drugs. He didn’t seem to be making any head road into hanging around.” A year after they met, George collapsed and died of a heart attack, aged 34.

For a time, too, she became friends with the talismanic Mac Rebennack, AKA Dr John, whom she refers to as “a dubious character in my life; a creator and a destroyer”. In his company, she began using heroin, which she had tried just once before as a young hippy drifter. I ask her why she was drawn to the drug. She ponders this for a long moment. “It’s not good to blame everything on my relationship with love, but, when I was younger, love was everything to me. I didn’t really have a self to hold on to when things turned bad. So, back then if a boyfriend said, ‘I don’t love you any more,’ I might go hurt myself. I wouldn’t try to kill myself, but I might go take drugs.” She pauses. “I think that we construct our personalities out of our family environment and mine was pretty unsettled. I was very loved, but that was probably the only healthy thing going on, but it’s possible that was not enough to keep me from being curious about the bad things in life, the forbidden things.”

Does she regret what she calls “the dark compressed days” of her addiction, which lasted around two years. “Well, with heroin, people just want you to say, ‘Oh, it’s so terrible’ and condemn it outright, but I think it’s wrong somehow to do that. There’s a reason why people get addicted to heroin. There is something there that they like, some kind of solace, some kind of numbing. In order to recover, I really think a person has to somehow acknowledge why they did it in the first place, maybe by saying: ‘I liked the drug and it almost killed me.’ Otherwise they are just pretending.”

Ever the survivor, Jones wrote the songs that ended up on her second album, 1981’s ambitious Pirates, as she emerged out of her addiction. Ever since, she has gone her own sometimes unpredictable, but always intriguing, way, recording several albums of covers, briefly embracing electronica (on 1997’s Ghostyhead) and making an angry protest album (2003’s The Evening of My Best Day). Between the two, she disappeared from public view to raise her daughter, Charlotte, whom she had with her former husband, Pascal Nabet-Meyer, a musician she met and married while living for a time in Paris in the late 1980s.

Listening again to Rickie Lee Jones’s great songs, which are scattered across her many albums, her otherness is striking. No one sounds quite like her, or goes to the places she goes to when the spirit moves her. She is a mercurial presence, impossible to pigeonhole or pin down, her songs as restless as her spirit. Reading her wild and wonderful book, one senses that, in a very real way, music was a calling that saved her life. “I guess so,” she says, “but something else I learned from writing the book is that I’m an optimistic person. In spite of my recklessness and throwing myself on the fire, my nature is to make something good out of what happens. I really didn’t know that until I laid it out in writing.”

Book extract: Last Chance Texaco by Rickie Lee Jones

When I was 23 years old I drove around LA with Tom Waits. We’d cruise along Highway 1 in his new 1963 Thunderbird. With my blond hair flying out the window and both of us sweating in the summer sun, the alcohol seeped from our pores and the sex smell still soaked our clothes and our hair. We liked our smell. We did not bathe as often as we might have. We were in love and I for one was not interested in washing any of that off. By the end of summer we were exchanging song ideas. We were also exchanging something deeper. Each other.

Tom had two tattoos on his bicep. He liked to don the vintage accoutrements of masculinity: sailor hats and pointed shoes. The more he tried to conceal his tenderness, the more he revealed a chafed and childlike nature. I adored him. He was my king. In bed he was the greatest performing lion in the world. I mean to say that Tom was never not performing.

Then quite suddenly, in November we were no longer seeing each other.

I spent the fall driving around with Lowell George, the charismatic guitarist from Little Feat, a local hero who kept his little feet “in the street” as it were. He found me there in my squalid basement encampment and we went drivin’ around in his Range Rover, seated high above the street studying various motels and apartments where he had spent time with past girlfriends. He showed me the hotel I would live in one day – the Chateau Marmont – and we sat in the living rooms of managers who would load him up with drugs for the chance to put his signature on paper. He flirted with them all like a child flirts with the devil, toying with their furious drugged-up machinations and escaping, like a child called home by his mother, just before he signed his soul away. Lowell seemed unconcerned about his own mortality. The play was the thing, and that boy could play the guitar.

In bed Lowell was a fat man in a bathtub. I mean to say that something about him was in another room, laughing, singing to himself. He was a handsome man, unhealthy, kind to a fault.

By June we did not speak much any more. He’d tried to obtain the publishing rights to Easy Money and Warner Brothers intervened. It left a very bad taste on both our tongues. I learned that lesson out of the gate; when push comes to shove, money trumps friendship.

The next summer I drove around with Dr John. It was a very different car, a station wagon used to take his kids to school and bring groceries home to his wife, Libby. He had been married a couple times and had a number of “sprouts”. He also had a ghost he kept with him, a thing that followed him, watched from behind the curtains in the hotel rooms and the plastic-backed chairs in the diners we visited. I mean to say it was his addiction. By the end of summer, he left his companion with me and I drove alone for the rest of the year…

The apex of my love life corresponds to my career success, and unfortunately my success corresponded with my drug use. My drug career was short-lived – three years from 1980 to 1983. I quit and headed to France. But the damage was done. I did drugs like I did everything else. On fire, with no back door.