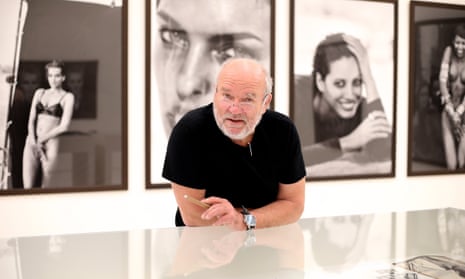

The portrait photographer Jane Bown used to grumble that nobody had faces any more, that people had become afraid to let the camera capture their true character in their visages. But the photographer Peter Lindbergh, who has died aged 74, could persuade even those whose image was their fortune – actors, musicians, fashion models – to show their real face to his lens, to reveal their identities and natural forms.

Lindbergh probably did not mean to change, radically, how fashion was shown in print, bringing it closer to the black-and-white photography he admired, Dorothea Lange’s portraits of the American poor, and photojournalism à la Henri Cartier-Bresson, but that’s what happened.

Not all at once, though. He began to work for US Vogue in the mid-1980s, and told its editorial director, Alex Liberman, that he didn’t like the way the women on its pages seemed to be there to display their husbands’ wealth. Liberman challenged him to show what he liked instead, and in 1988 Lindbergh did just that, shooting half a dozen models in nothing but white shirts and a happy mood messing about on Santa Monica beach, adding only a little light to the scene. The images were glorious, about how you wanted to feel more than how you desired to appear, but Liberman and the then editor, Grace Mirabella, consigned them unused to a drawer.

Soon after, Anna Wintour succeeded Mirabella, found the rejects, and one cropped image made it into the magazine; she commissioned from Lindbergh her first cover, November 1988, of a model, Michaela Bercu, in couture jacket and cheap jeans slung low to expose a soft, bare belly. It broke all rules: Bercu’s hair was blown about, her eyes were almost closed and she was smiling, she wore marginal makeup and zilch jewellery. The worried printers rang Wintour to ask if there had been a mistake: was that the right pic?

It so was. When Liz Tilberis, editor of UK Vogue, asked Lindbergh to shoot the woman of the decade for a January 1990 cover, he replied there couldn’t be just the one. So he got a couple of the beach band back together for a shoot in downtown Manhattan, and added newcomers. Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Tatjana Patitz, and Christy Turlington were shown as their forceful selves, all “quite undone … like being photographed right when you wake up in the morning”, according to Crawford.

The tight grouping has been imitated by many hen-party snaps since: Lindbergh caught early the new social phenomenon of all-female parties out for their own good time. His portraits of men are just as below-the-skin deep, but “women are more open and courageous, they have more guts and take many more risks”.

How he achieved the truth in his pictures explains his success. Several famous images, such as of Kate Moss no longer capitalising on her youth, came out of long conversations with the model, asking how she felt about life, about herself. “I look at women for who they really are,” he said, “perhaps this is what leads them to trust me.” Those women then willingly revealed characterful faces, aged hands, bodies that might be judged imperfect.

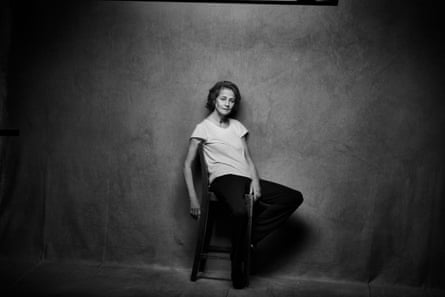

The third of his Pirelli calendars, in 2017 (following those in 1996 and 2002) approached the actors Helen Mirren and Charlotte Rampling with the same kind candour as the young Lupita Nyong’o. Lindbergh said: “This should be the responsibility of photographers today, to free women, and finally everyone, from the terror of youth and perfection.”

He also had a novel eye for locations, often industrial or on the rough side of town (the designer Donna Karan recruited him early on for her campaigns because he saw New York afresh), and a narrative drive. His ad work for, among others, Dior, Armani, Prada and Calvin Klein told stories about places and people, not just products, as did his work for musicians such as Tina Turner and Beyoncé.

His pictures look like film stills, with action and time stopped, and he also directed several successful documentaries, including Inner Voices (1999), winner of best documentary at the Toronto film festival the following year, and a film about his friend the choreographer Pina Bausch (2002).

It had taken a long and wide apprenticeship to life as well as art for Lindbergh to establish himself. He was born Peter Brodbeck in Leszno, a Polish city then annexed to Nazi Germany, and his German family fled west near the end of the war, settling in the industrial landscape of Duisburg. Schooling was minimal: he left at 14 and worked as a window-dresser in a local store chain. He later loved arranging backgrounds for shoots, layering found objects and drapes with all technical details showing.

He had a clear artistic gift and pursued it, moving to Lucerne, then to Berlin, where he took classes at the Academy of Fine Arts, then Arles, the chosen city of his favourite painter, Van Gogh; he hitchhiked around Spain and Morocco.

Returning to Germany, to study art at the Kunsthochschule in Krefeld, he had showed in galleries before discovering a delight in photography when taking pictures of his brother’s children. He found a job as assistant to the photographer Hans Lux, then opened his own studio in Düsseldorf in 1973, during which time he changed his name to Lindbergh, after finding there was another photographer named Brodbeck. In 1978 he began to work for Stern, the German equivalent of Life and Paris-Match, the magazines whose pictures had shaped his aesthetic, and joined other Stern photographers, including Helmut Newton, in the international glossies, establishing his base in Paris.

Lindbergh’s goodbye was the current cover of UK Vogue, guest-edited by the Duchess of Sussex: portraits of 15 women, among them the activist Greta Thunberg; the New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern captured by video link (although Lindbergh always preferred actual film to digital work); and original muse Turlington. All raw, and all different.

Lindbergh’s first marriage to Astrid ended in divorce. He is survived by the photographer Petra Sedlaczek, whom he married in 2002, and by four sons, Benjamin, Jérémy, Simon and Joseph.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion