I invested a lot in my fitness. My personal network [of therapists] cost me 10% of my net salary, several hundreds of thousands of euros. But it was absolutely the right decision and it paid off as after two seasons I extended my contract by a further three years. I wouldn’t have been able to play for a top club for seven years in the Premier League without these additional therapies.

My experience has taught me that you simply cannot do enough. For example, I was a big fan of yoga from the beginning because I had seen that it improved stability and flexibility.

Even at the age of 33 I was one of the most flexible at Arsenal when it came to my back muscles. Hardly anyone came to the yoga sessions that the club offered. Often there were only four of us: Héctor Bellerín, Nacho Monreal and Tomas Rosicky.

The youth players who were promoted to the first team smiled at these exercises. They thought we were meditating. They were happy with the ball at their feet but for everything else there was a lack of desire. “I play football and go to training. That’s enough.”

But no, it isn’t enough when you want to maintain a certain level for a long time or want to improve.

Either you are learning from scratch, from your parents and the teachers and coaches around you, to take responsibility, or you don’t do it at all. This is the kind of dumbing down we must fight against.

In the autumn of 2017 an under-18 player came and asked whether we could sit down for a chat. I nearly fell over, I was so surprised. That hadn’t happened in the six and a half years I had been there. He wanted to speak to me about leadership.

I used a lot of energy trying to convince team-mates they should do more for their bodies and try new things. But working long term to improve their weaknesses? Hardly anyone.

When I injured myself against Sunderland [in the 2011-12 season] I started working with Lars Lienhard. A former athlete, he is a sports scientist as well as a pioneer when it comes to neurally controlled training.

Working with him was a huge success. We always assume that we can run and see properly because nothing hurts. But that is a mistake. Lars showed me that our eyes are a big factor in everything, above all when it comes to our timing.

On my right side my timing was super but I had the feeling my left eye was not really up for it. Why was that? And was it possible to train and improve [the left eye] so that I didn’t have to turn my whole body in order to look left? It all meant that in 50% of the times the ball came towards me my brain said: “Hey, I can’t really see that ball so I’m not going to jump for it.”

And as my left eye was not really looking at the ball I was always twisting my neck to use my dominant right eye.

Football doesn’t really deal with those things, despite the fact they can be decisive. Players would rather lift weights, stand on their own with their dumbbells – but how does that help me on the pitch?

During the exercises with Lars one could see quite clearly that my eyes were moving differently when an object was approaching me. My left eye always remained in the middle rather than focusing on the object.

He showed me how to make my left eye stronger. I had a patch on my right eye, forcing my left eye to focus on the objects. And after a few weeks I could really notice the difference in games. If there was a high ball from the left I had a much better feeling for where it would end up.

With Lars’s help I stayed injury-free for four and a half years. Meeting him changed my life as a footballer.

The important thing was to do exercises myself before games as well to adjust the eyes. One example was a kind of push-up for the eyes. You bring a pencil in towards your nose and force your eyes towards the middle. When you do that at the training ground a lot of people think: “What is he doing now? Is he completely stupid?”

Mainly I was doing it at home or in the hotel room. I had six or seven exercises that I did, sometimes just before kick-off in the dressing room. I didn’t care what the others thought or if they laughed. But you saw again that something new, something unknown, led to laughter rather than people asking: “What are you doing there?”

Footballers are used to working only three hours a day. And out of the three hours they are at the training ground they are on their mobiles for half of that.

We have all the money in the world but do not realise how important the body is. A player on average has a seven‑year professional career, 10-15 if everything goes right. You have to do everything possible to be at your maximum.

A lot of players don’t even know what maximum is – for them it is about having fun on the pitch. But there is more to being a professional than that.

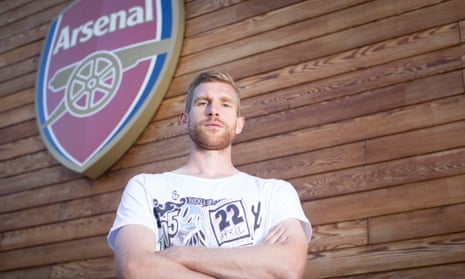

In my new role as Arsenal academy manager I will do everything I can to challenge the young players’ mindsets. I want to challenge them so that they are ready to take on new ideas and protect them from being injured, when it comes to their body and soul.

I want to convince them they have to do something to get to the top of the world and I want to be an example for them. For me there wasn’t really a way up but somehow I made it there anyway, because I did everything I possibly could to give me the best chances to succeed. Talent is what you make of your situation.

This is an edited extract from Weltmeister ohne Talent by Per Mertesacker (with Raphael Honigstein), which was released in German on 11 May and published by Ullstein Verlag

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion