The Big Picture

- Paul Newman's miscasting as Billy the Kid in The Left Handed Gun highlights the dissonance between self and image in a tragic Western tale.

- The comic book adaptation of Billy's legend emphasizes the cyclic nature of violence and the loss of autonomy in storytelling.

- The Left Handed Gun combines classical Western themes with '50s teen melodrama, reflecting on youth culture and disillusionment.

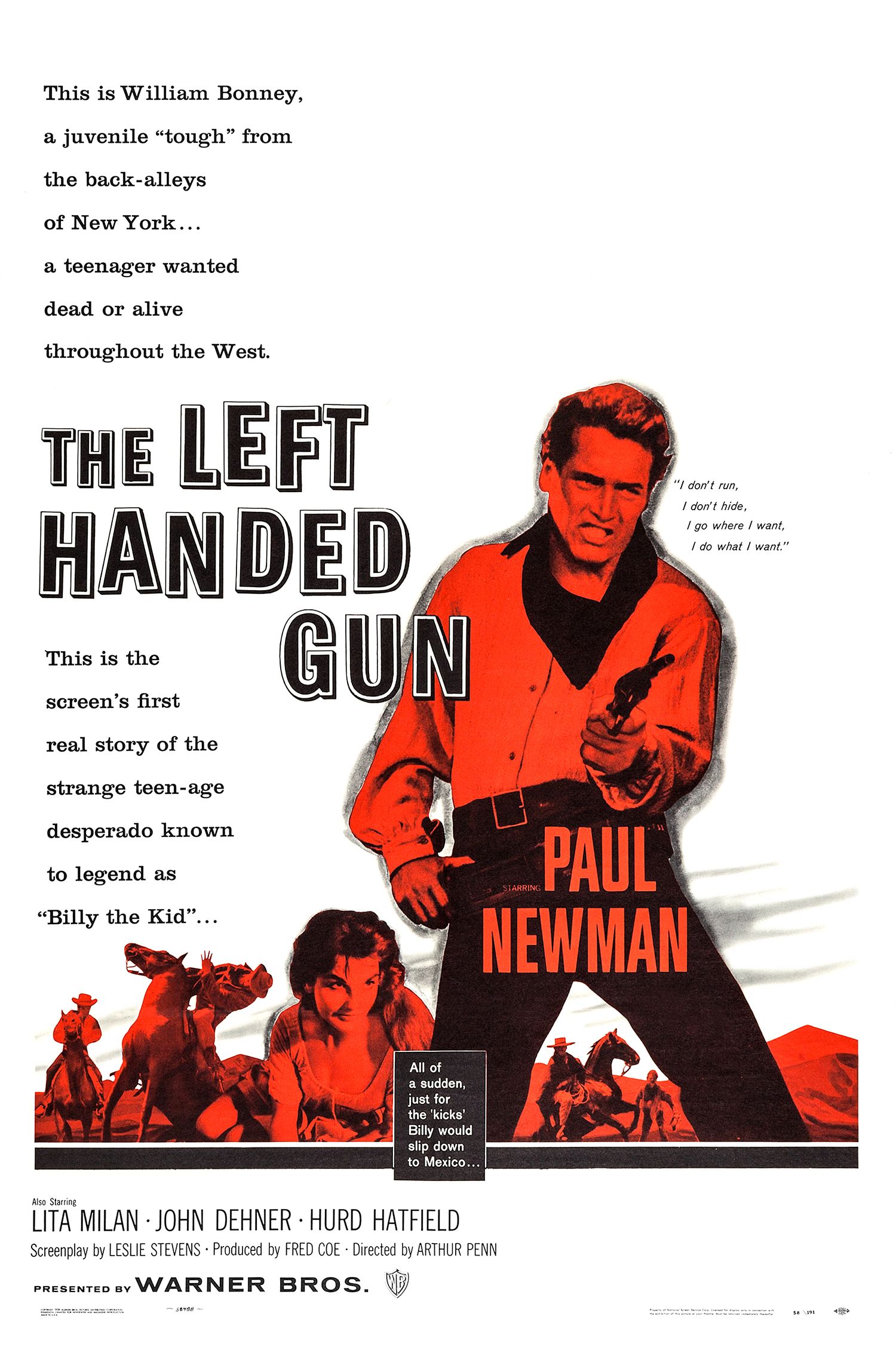

10 years before he recapitulated the outlaw legend of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, Arthur Penn made his directorial debut with a film about another famous outlaw. Paul Newman plays Billy the Kid in The Left Handed Gun (1957), a tragic Western whose vision of the Wild West is oriented around the dissonance between self and image, and which examines that dissonance with languid melodrama. A classical Western through and through, The Left Handed Gun combines those frontier sensibilities with those of a '50s teen melodrama. Think James Deen in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) but with a six-shooter and a cowboy hat. Before Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), Penn renders the story of Billy as a disaffected youth, whose temperamental excess leads to an endless cycle of violence and a cult of celebrity that even he can't stomach.

The story, inspired by the true events of the Lincoln County War, sees a wayward Billy set down a path of revenge for his murdered boss, a kindly cattle rancher. Billy's exploits only fuel more and more violence, violence which catches innocents in its path and traumatizes witnesses. His sordid adventures also lead to his coming to terms with his own myth, trapped by the light between himself and the images that pervade pulp novels and valorize his actions. First, he loses control of his environment, then his image, and finally himself. Ironically, the same year as the film's release, it was adapted into a comic book. This presents a bitter twist to the film's themes. The comic surely reads in a way not dissimilar to the ones that plagued Billy in the film. However, it also addresses one of the few major criticisms that persists about The Left Handed Gun, the miscasting of Paul Newman.

The Left Handed Gun

After his employer is murdered by rival cattlemen, a troubled and uneducated young cowboy vows revenge on the murderers.

- Release Date

- May 17, 1958

- Director

- Arthur Penn

- Cast

- Paul Newman , Lita Milan , John Dehner , Hurd Hatfield , James Congdon , James Best , Colin Keith-Johnston , John Dierkes

- Runtime

- 102 Minutes

- Writers

- Leslie Stevens , Gore Vidal

The Brooding Angst of James Deen Meets the Cowboy Cool of Gary Cooper in 'The Left Handed Gun'

The Left Handed Gun was one of Newman's early major roles, and to be frank, the then-33-year-old actor was severely miscast as Billy the Kid. He's far too old for the role, and Newman's stern brow and authoritative presence cancel the youthful rebelliousness that the role is meant to capture. However, Newman's sheer talent and screen presence go a long way to alleviate these issues, and he turns in a truly memorable performance. Billy begins the film in a sorry state but is picked up by a generous cattle rancher named Tunstall (Colin Keith-Johnson). Tunstall is kind and generous to Billy, but is gunned down by a rival cattle baron and his three co-conspirators. Two of Tunstall's other men, Tom (James Best) and Charlie (James Congdon), join up with Billy to seek revenge. Billy leads Tom and Charlie like a band of dispossessed hoodlums, sweeping them up with his charisma and apparent principles.

The first two murders are strategically planned. At the beginning of the film, Billy is still fighting for control of his environment, and this is reflected cleverly in J. Peverell Marley's cinematography. Billy designs the killing of the cattleman and his crony from his room on the second story of the saloon. In the fog that coats the window overlooking the town's thoroughfare, Billy uses his fists, clenched over four bullets, to draw a diagram designating where he and his boys will ambush their adversaries. A circle here, a line there, Billy seems to have dominion over the space ahead of them. The trio provokes the cattlemen into drawing first, ambushing them the second they unclip their holsters.

It's a facile pretense, and the act of violence is immediately recognized as murder. The film doesn't shy away from the toll of violence here, either. Children and their mothers look somberly at the bodies in the street, traumatized by the brutal killings. The townspeople form a mob and chase Billy into the town preacher's home. The preacher had shown Billy great empathy earlier, but his home is burned down, and his wife is shot in the crossfire. Billy makes his escape, weighed down by the toll of his actions. Newman's performance is melodramatic, matching the likes of Marlon Brando and Deen, but reigned with an intense melancholy.

Though Newman's age and stern appearance partly works against him here, the saving grace is that he is able to bridge the gap between hard-nosed outlaw and smoldering youth. Newman always excelled as charismatic tough guys, and he plays Billy with a masculine gravitas that always shines through his juvenile demeanor. When he's not messing around with his friends or throwing a violent tantrum, he is forthright and sharp, echoing the pragmatic disposition of Gary Cooper's sheriff in Fred Zinneman's High Noon (1952). For moments of melodrama, though, Newman screams to the heavens, falls to his knees, and clenches his fists at the sky. These moments would feel right at home in Rebel Without a Cause or East of Eden, where James Deen plays to the abundance of teenage emotion with excessive performances. The transition between the two registers can be a jarring element of Newman's performance, but when it works, it creates an image of youth culture that is somehow equal parts romantic and cynical. Going further than the expressive heights of those conventional teen melodramas, it engages rousing folk-tales as a story of lost youth.

The Comic Book Adaptation of Billy the Kid's Legend Was an Ironic Meta-Twist

The same year as the film came out, it was adapted into a comic in the anthology series Dell Four Color. This is an eerie mirror of the tragedy in The Left Handed Gun, where Billy becomes haunted by his own legend. As the film goes on, Billy develops a relationship with Pat Garrett (John Dehner), an old friend who takes pity on the wayward youth. Pat is eventually forced to take on the role of Sheriff and pursue Billy and his buddies. The more violence Billy causes, the more it comes right back at him, until eventually he's alone in the world, his purposelessness compounded by the appropriation of his image and stories by cheap, pulp Western novels.

One memorable scene toward the end of the film finds Billy in his hideout, covered in newspaper clippings and bounty postings with his name on them. What began as a cathartic way to be noticed by the same systems that shirked him is now trapping him. There's a subtext that speaks to the disillusionment of the emerging youth culture of the '50s, and the feeling that the walls are closing in even as the world seems to expand. It's a smart fusion of the thematic and tonal palettes of Westerns and teen melodramas, and it prefigured the approach to recapitulating folk-hero legends for contemporary audiences in Penn's later Bonnie and Clyde (1967). For most of its length, the comic itself seems more like the kind of mythologizing pulp-entertainment that tortured Billy in the film. Its bright primary colors and dramatic imagery cast the story as heroic and exciting.

There is an upside and there is a downside to this. The upside: The flexibility of comic books' illustrative style is such that the artist could soften this version of Billy to better resemble the troubled youth that the story calls for. Billy in the comic looks younger and more naive than in the film, while still broadly resembling Newman. However, the immortalization of Billy's legend into yet another pulp adventure tale provides a bitter meta-text to the comic. That being said, the comic is more explicitly self-aware than the film. Its ending page is dedicated to addressing the immateriality of Billy's legend, pointing out inconsistencies in the stories that are told compared to the records of the time.

The film expresses its themes with vibrant formalism, whereas the comic addresses its own limitations. It was exactly this kind of medium that divorced our antihero from his own story and robbed him of autonomy in his tragic tale. There's an unavoidable irony that occurs to the reader here, that the audience who eats this stuff up is not altogether different from the audience for the stories that broke down Billy's sense of self. We are forced to confront that, no matter if we're being presented with Billy the legend, Billy the wayward boy, Billy the villain, or Billy the tragic hero, no legend or folk tale can ever truly capture Billy the Kid.

The Left Handed Gun is available to stream on Sling TV in the U.S.