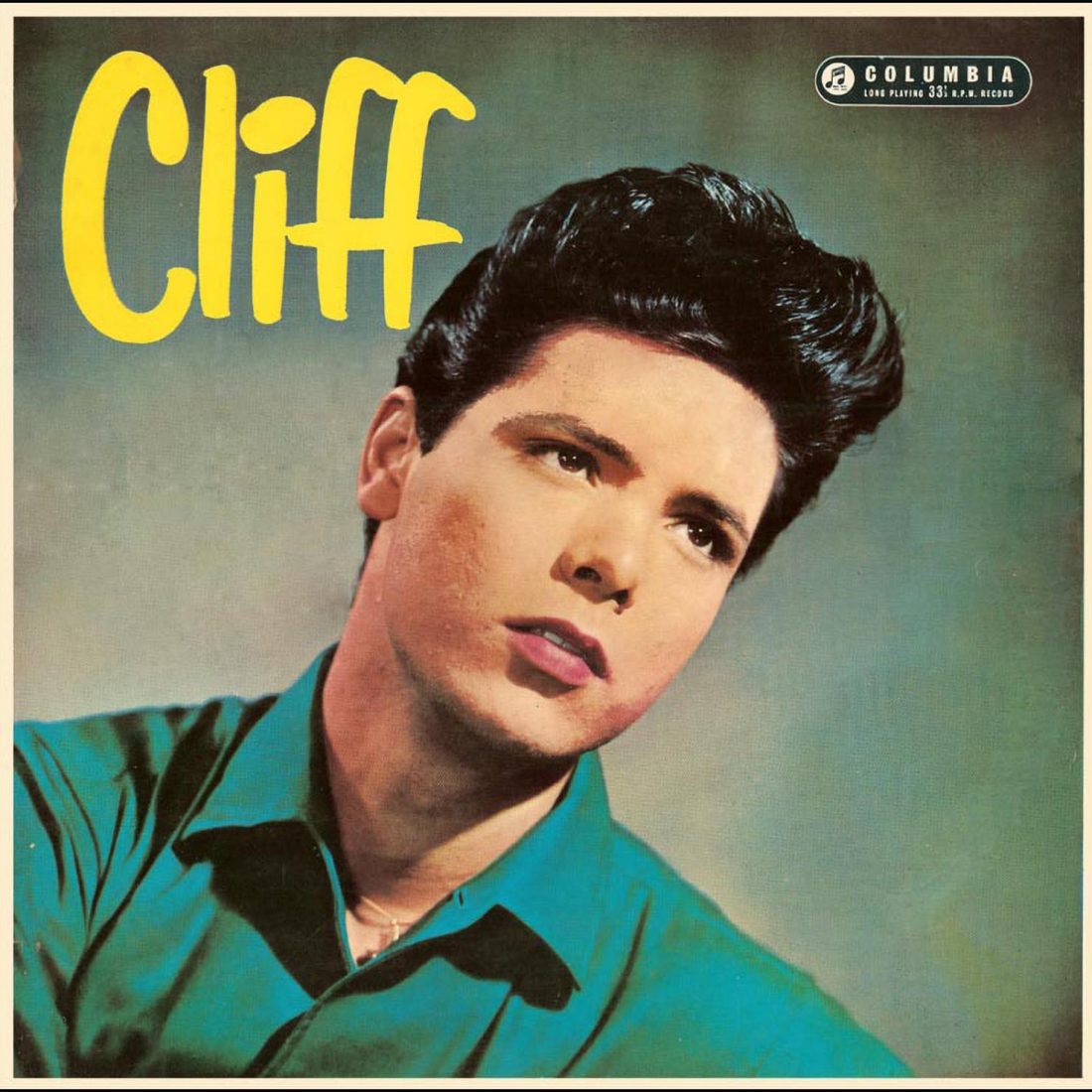

Released in April 1959, Cliff Richard’s debut long-player was an electrifying introduction to one of the UK’s first ever rock’n’roll stars and proved that we could rock just as hard as those across the pond…

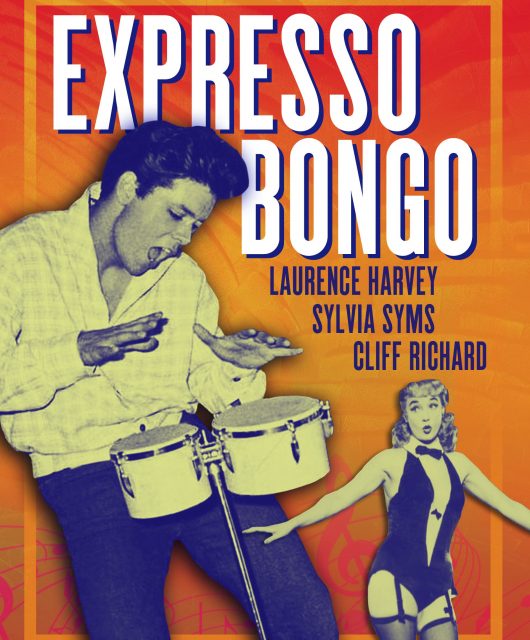

On the evening of 9 February 1959 Cliff Richard arrived at EMI Recording Studios on Abbey Road in London to record his first album. With three hit singles and sold-out concert halls across Britain, Richard was one of the most successful homegrown rock’n’roll stars to date. The album would cap a whirlwind seven months of his rise through a string of hits and electrifying TV appearances.

With Richard’s initial rise to fame rooted in live performances, Columbia Records producer Norrie Paramor insisted on live recordings for the singer’s first album. Remote concert recording was an iffy proposition at best, and therefore staging a concert in Abbey Road’s largest recording room, Studio 2, seemed the best option.

With over 198 square metres of floor space and a ceiling two storeys high, Studio 2 was one of the largest recording studios in the world, more than adequate to host a sizable concert. For the album sessions, a stage was constructed against one wall of the studio, directly below the large glass window of the second story control room overlooking the recording area. Requiring an enthusiastic audience, Columbia sent invitations to London-area members of Richard’s fan club. Several hundred teenagers secured tickets for the two nights of recording.

‘The album would cap a whirlwind seven months of

Cliff’s rise’

Also on hand were Richard’s band, The Drifters. While the group backed Richard on all of his live appearances, Paramor generally preferred to work with more experienced musicians for recording sessions. That had been the case for Richard’s first session with Columbia in July 1958 where half of The Drifters were replaced by session players. By the time of the album sessions, the line-up of The Drifters had changed. All of the group’s original members had been replaced for various reasons over the previous seven months. The current line-up — Hank Marvin on lead guitar, Bruce Welch on rhythm guitar, Jet Harris on bass and Tony Meehan on drums — was a powerful group of young musicians whose talent made up for their lack of experience. In just a few months, the group would change its name to The Shadows (due to a lawsuit from the US vocal group, The Drifters) and would gain a reputation as one of Britain’s greatest rock’n’roll bands with a string of instrumental hits. Furthermore, Paramor knew the chemistry between the singer and the band was a vital element in capturing the excitement he wanted on the album.

Eighteen songs were initially chosen for the two nights of performances with nine songs to be recorded each night. Move It, Richard’s first single and his biggest hit to date, was an obvious choice for inclusion, while his other original songs were rejected in favour of covers of popular American rock’n’roll tunes regularly featured at his live performances. British rock’n’rollers’ reliance on covers in live shows was not unusual at the time. Only a few American rock’n’roll artists were able to tour in the UK because of strict regulations on live performances by non-British artists. Live covers by homegrown artists were as close as British youth could come to seeing their American heroes in the flesh.

Rounding out the setlists for the two nights were a handful of instrumentals by The Drifters. Columbia Records originally signed Richard to the label as a solo artist with no provision for recording the band separately. After the success of Move It, Columbia reversed their position and signed The Drifters to a separate contract. The band’s first instrumental single was released just a week before the Cliff album sessions.

The first night of recording, and side one of the album opened with Apron Springs, a song originally recorded and released by the mysterious “Billy the Kid” on Kapp Records in the US. Although the song is often credited to R&B singer Billy “The Kid” Emerson (who did originate the rockabilly classic Red Hot), the Billy the Kid in question was an unknown white singer whose identity has never been conclusively verified. How Richard learned the song is also a mystery considering the album sessions took place less than four weeks after the original version was recorded. Whatever the explanation, Richard delivered a supercharged version bringing the album roaring out of the gate.

The Willie Dixon composition My Babe follows. Recorded by Little Walter on Chess Records in January 1955, the song hit No.1 on the Billboard R&B chart and was released in the UK as the lead track of a Little Walter EP in October 1956. Although My Babe didn’t chart, it immediately became a favourite of British blues fans and gained further traction with rock’n’roll fans after Ricky Nelson’s version was released in the UK in November 1958.

Down The Line was written and originally recorded by Roy Orbison under the title Go! Go! Go! as the B-side to his first hit, Ooby Dooby. Although it received little notice at the time, a year later fellow Sun Records star Jerry Lee Lewis recut the song under the title Down The Line as the B-side to his hit single Breathless. Lewis’ version attracted Richard’s attention, becoming his favourite Jerry Lee Lewis recording and a standard of his own live performances.

I Got A Feeling was another perfect fit for Cliff Richard. Written by professional songwriter Baker Knight and a No.27 hit for Ricky Nelson in the UK in the autumn of 1958, Richard upped the tempo and delivered a harder rockin’ version than the original. The Drifters follow it up with the first of their instrumentals, Jet Black, written by bass player Jet Harris and debuting on the album. The Drifters would soon re-record a studio version for their second single in June 1959.

Richard jumps back into the show with Elvis Presley’s Baby I Don’t Care. Recorded for the soundtrack of the movie Jailhouse Rock, Presley’s version was first released in the UK on the Jailhouse Rock EP in April 1958. Richard demonstrates his mimicry of Elvis’ phrasing with his hot version, ramping up the tempo from the original.

Next up on the album is one of the two songs Richard and The Drifters recorded at a later, separate session without an audience. Both songs were ballads, the only two included on the album, and were recorded at a different session, presumably to ensure proper sound mix levels as well as Paramor’s desire to use the Mike Sammes Singers on backup vocals.

‘Move It, Richard’s first single and his biggest hit to date, was an obvious choice for inclusion’

The first ballad was a faithful cover of the Ritchie Valens love song Donna. Released in the US in late 1958, the record hit No.2 in January 1959, and was popular in the UK, although failed to chart. Richard’s version particularly resonates considering a plane crash in Clear Lake, Iowa took Valens’ life only a few days prior to the session.

To close out the 9 May session and side one of the album, Richard and The Drifters ripped into his first hit, Move It. Written by former Drifters member Ian Samwell, it was one of the first truly authentic British born and bred rock’n’roll records to achieve huge chart success. The song was originally slated as the B-side of Richard’s first single with a cover of the Bobby Helms pop ditty Schoolboy Crush as the A-side. Plans changed when television producer Jack Good insisted Richard perform Move It for his first appearance on the TV programme Oh Boy!. Good’s instincts proved to be right on the money as Richard’s hot performance sparked a nationwide craze for the song, pushing it to No.2 on the charts in the autumn of 1958.

The next night, Cliff and The Drifters returned to Abbey Road to record side two of the album, kicking off the performance with the Little Richard classic, Ready Teddy. Richard’s love of Little Richard was plainly obvious considering the former “Harry Webb” had been inspired to adopt the name “Cliff Richard” partially as a tribute to his rock’n’roll hero. Richard followed it with Too Much, another Elvis Presley song. Released in the UK in the spring of 1957, the song became a No.9 hit for Presley and was a fixture in Richard’s live sets.

Similar to Apron Strings from the first night of recording, Don’t Bug Me Baby was another rather obscure rockabilly single from the US. Originally recorded by Milton Allen for RCA, the record was only released in the US. Presumably Richard learned the song from an imported single.

Richard took a break from the mic as The Drifters moved to the forefront again with the instrumental Driftin’. Written by The Drifters’ lead guitarist Hank Marvin, the tune demonstrates an obvious Duane Eddy influence. Shortly after the Cliff album, The Drifters returned to Abbey Road to re-record the song sans audience for the B-side of the Jet Black single.

Richard re-takes the mic with a faithful rendition of Buddy Holly’s That’ll Be The Day. As with the Ritchie Valens cover from side one, the song carried extra meaning in light of Holly’s recent demise. The Drifters then moved back to the spotlight with a revved-up version of Gene Vincent’s Be-Bop-A-Lula. It’s an unusual track for a band primarily known for instrumentals, featuring harmony lead vocals from Hank Marvin and Bruce Welch, and inspired by The Everly Brothers’ arrangement of the song for their 1958 debut album.

Danny was the second ballad from the follow-up, audience-free session. As with Donna, cheers from the audience were overdubbed onto the beginning and end of the song to integrate it into the live recordings. Danny was written by American songwriters Ben Weisman and Fred Wise as the theme song for the proposed Elvis Presley film, A Stone For Danny Fisher. Elvis recorded the song on 11 February 1958 for the movie’s soundtrack, but after the film’s title was changed to King Creole, Danny was dropped from the movie. Demos of the song continued to circulate and eventually made their way to the UK where Richard picked up the tune, along with fellow Brit rock’n’roller Marty Wilde who recorded his own version shortly after the Cliff album sessions.

Elvis’ version was finally released in 1978, on the album, A Legendary Performer – Volume 3.to close out the second night of performances, Richard turned to another favourite from Jerry Lee Lewis, Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On. Originally recorded by American R&B artist Big Maybelle, Lewis’ version became his first hit single, reaching No.3 in the US and No.8 in the UK in the spring of 1957. Richard’s version captures the energy of Lewis’ version while toning down its lasciviousness, and The Drifters successfully transpose the piano-driven rocker to guitars through their hot arrangement.

In addition to the 16 songs featured on the final album, four more songs were originally scheduled for recording. The Elvis song One Night was definitely recorded during one of the sessions but was dropped from the final album. It would eventually appear on the 1997 Cliff Richard compilation album, The Rock’n’Roll Years 1958-1963. Paperwork has surfaced indicating the Conway Twitty hit, It’s Only Make Believe, The Weavers’ Kisses Sweeter Than Wine and the Eddie Fontaine rocker, Nothin’ Shakin’ (But The Leaves On The Trees) were scheduled for the sessions, but master tapes have never been located.

Released in April 1959, Cliff was an immediate hit, rising to No.4 on the UK chart. The album was also popular in France, as Dance With Cliff Richard and released with an alternative cover. Although all the tracks for Cliff were recorded in stereo on Abbey Road’s BTR3 two-track tape machine, the album was released in mono only. Stereo mixes, which differed from the mono version primarily in the amount of crowd noise, appeared only on the Cliff No.1 and Cliff No.2 EPs, which each contained five tracks culled from the album. The full stereo mix of the album was not released until EMI’s 1998 reissue on CD.

Despite its lack of original tunes, Cliff was 16 tracks of pure, unrelenting rock’n’roll, establishing Cliff Richard as the UK’s first “authentic” rocker. Before Richard’s rise to the top of the chart, the majority of British attempts at recording rock’n’roll relied on teen idols primarily recruited for their good looks, established studio musicians and gimmicky songs bordering on parody. The breakout success of Cliff Richard confirmed British singers and bands could rock as hard as their American counterparts. The Drifters/Shadows’ eventual success as a chart-busting instrumental act inspired hundreds of British youth to form their own rock’n’roll combos.

Unfortunately, Cliff Richard’s first album of undiluted rock’n’roll also proved to be his last. Producer Norrie Paramor suspected Richard was capable of bigger chart success with mainstream pop, and the runaway success of the pop single Living Doll in the summer of 1959 confirmed his theory. Richard’s second album, Cliff Sings, released in November 1959, inaugurated the practice of splitting his albums between rock’n’roll songs backed by the recently rechristened Shadows and pop songs backed by the Norrie Paramor Orchestra.

Although Cliff Richard recorded more classic examples of British rock’n’roll, he would never again capture lightning in a bottle in the same manner as his first LP. Sixty years later, Cliff still brings rock’n’roll excitement to life with the simple drop of a needle.

Randy Fox