Sachsenhausen (Oranienburg): History & Overview

The Sachsenhausen concentration camp was built in July 1936, by teams of prisoners transferred there from small camps in the Ems area and elsewhere. It was located near the administrative center for all of the concentration camps in Oranienburg and became a central training facility for SS officers. On the front entrance gates to Sachsenhausen is the infamous slogan Arbeit Macht Frei (German: “Work Makes [You] Free”).

- Location: Germany, 35 km from Berlin

- Established: 1936

- Liberation: April 22nd, 1945, by a unit of the 47th Soviet Army.

- Estimated number of victims: 30 - 35,000

- Subcamps: 44 subcamps and external kommandos (click here for a complete list)

Sachsenhausen prisoners eat a meal in the mess hall (USHMM Photo). |

|---|

In August and September 1938, 900 inmates were transferred from Esterwegen to Sachsenhausen in order to take part in the continued construction of the camp. Due to the lack of food and the incredible cruelties of the SS, most of them died during this period. By the end of September, the Konzentrazions Lager Sachsenhausen was ready, and the first political prisoners arrived in the camp.

Sachsenhausen was intended to set a standard for other concentration camps, both in its design and the treatment of prisoners. The camp perimeter is, approximately, an equilateral triangle with a semi-circular roll call area centered on the main entrance gate in the side running Northeast to Southwest. Barrack huts lay beyond the roll call area, radiating from the gate. The layout was intended to allow the machine gun post in the entrance gate to dominate the camp, but in practice, it was necessary to add additional watchtowers to the perimeter.

The standard barrack layout was two accommodation areas linked by common washing and storage areas. Heating was minimal. Each day time to get up, wash, use the toilet and eat was very limited in the crowded facilities.

There was an infirmary inside the southern angle of the perimeter and a camp prison within the eastern angle. There was also a camp kitchen and a camp laundry. The camp’s capacity became inadequate, and the camp was extended in 1938 by a new rectangular area (the “small camp”) northeast of the entrance gate, and the perimeter wall was altered to enclose it. There was an additional area (sonder lager) outside the main camp perimeter to the north; this was built in 1941 for special prisoners that the regime wished to isolate.

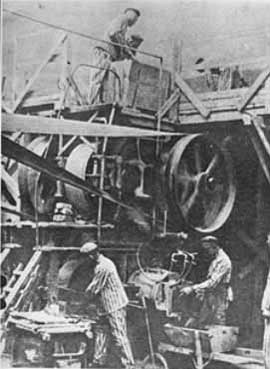

An industrial yard, outside the western camp perimeter, contained SS workshops in which prisoners were forced to work; those unable to work had to stand to attention for the duration of the working day. Heinkel, the aircraft manufacturer, was a major user of Sachsenhausen labor, using between 6,000 and 8,000 prisoners on their He 177 bomber. Although official German reports claimed “The prisoners are working without fault”, some of these aircraft crashed unexpectedly around Stalingrad, and it’s suspected that prisoners had sabotaged them. Other firms that used Sachsenhausen labor included AEG.

Inmates at forced labor in the brickworks at the Klinker-Grossziegelwerke opposite the main camp (USHMM Photo). |

|---|

The camp was secure, and there were few successful escapes. The perimeter consisted of a three-meter-high wall on the outside. Within that, there was a path used by guards and dogs; it was bordered on the inside by a lethal electric fence; inside that was a “death strip” forbidden to the prisoners. Any prisoner venturing onto the “death strip” would be shot by the guards without warning.

Before the outbreak of World War II, most of the inmates were German communists or Soviet prisoners of war, including some Jewish prisoners. In November 1938, just after the events of Kristallnacht,1,800 Jews were jailed in Sachsenhausen, and about 450 of them were subsequently murdered in the following weeks.

In September 1939, thousands of communists, social democrats, and former trade union leaders were arrested in Germany. About 5,000 of them were sent to Sachsenhausen, as well as 900 Jews. At the end of September 1939, there were 8,384 prisoners in the camp. In November 1939, this number increased to 11,311 prisoners. Also, at this time, the first Typhus epidemic broke out. Because the SS refused to provide the prisoners with any medical care and due to the lack of food, hundreds of inmates died in the following weeks. The dead were originally sent to the crematories installed in nearby Berlin, located not far from Sachsenhausen. As the war progressed, the first crematory was built in Sachsenhausen in April 1940.

After the start of the war, the number of deaths in Sachsenhausen increased dramatically. In 1939 more than 800 prisoners died there, but in 1940 this number increased to nearly 4,000.

Like all other Nazi concentration camps, the conditions of life in Sachsenhausen were incredibly barbaric. There were daily executions by shooting or hanging, and many more died as a result of casual brutality and poor living conditions and treatment. Sachsenhausen was not intended to be used as an extermination camp, however. Most of the Jewish prisoners were sent to camps in the East. In October 1942, all of the Jewish inmates of Sachsenhausen were sent to Auschwitz.

Sachsenhausen prisoners stand in columns under the supervision of a camp guard - 1938 (USHMM Photo). |

|---|

Camp punishments were harsh. Some were required to assume the “Sachsenhausen salute,” whereby a prisoner would squat with his arms outstretched in front. There was a marching strip around the perimeter of the roll call ground, where prisoners had to march over a variety of surfaces, to test military footwear; between 25 and 40 kilometres were covered each day. Prisoners assigned to the camp prison would be kept in isolation on poor rations and some would be suspended from posts by their wrists tied behind their backs. In cases such as attempted escape, there would a public hanging in front of the assembled prisoners.

On January 31, 1942, the SS forced a team of inmates to build the so-called “Station Z” in a section of the industrial yard. This new installation was built solely for the extermination of the prisoners. On May 29th, 1942, the SS invited dozens of high-ranked Nazi officials for the inauguration of the new installation. In order to illustrate its effectiveness and efficiency, 96 Jews were shot execution style. The name Station Z was intended to be a joke, according to the Memorial Site built there in later years, because the entrance to the camp was through Building A, which was the gatehouse, and Station Z was the exit from the camp for those who were executed.

In March 1943, a gas chamber was added to “Station Z.” This gas chamber was used until the end of the war. The number of gassed victims is unknown because the transports for gassings were not registered in the entry registers of the camp.

With the advance of the Red Army in the spring of 1945, Sachsenhausen was prepared for evacuation. On April 20–21, the camp’s SS staff ordered 33,000 inmates on a forced march Northeast. They were divided into groups of 400. The SS intended to put them on ships and then sink those vessels. Most of the prisoners were physically exhausted, and thousands did not survive this death march; those who collapsed en route were shot by the SS.

On April 22, 1945, the camp’s remaining 3,000 inmates, including 1,400 women, were liberated by the 47th unit of the Red Army and the Polish 2nd Infantry Division of Ludowe Wojsko Polskie. Most of them were starving, ill, and too weak to welcome their liberators. Like in several other camps, and despite the medical care they received from the Allied armies, many inmates died in the days following the liberation.

A survivor of Sachsenhausen the day of its liberation by the Soviet Army. |

|---|

About 200,000 people passed through Sachsenhausen between 1936 and 1945. Some 100,000 inmates died there from exhaustion, disease, malnutrition or pneumonia from the freezing winter cold. Many were executed or died as a result of brutal medical experimentation.

Sachsenhausen was also the site of the largest counterfeiting operation ever, perhaps. The Nazis forced Jewish artisans to produce forged American and British currency, as part of a plan to undermine the British and United States economies, courtesy of Sicherheitsdienst (SD) chief Reinhard Heydrich. Over one billion pounds in counterfeited banknotes were recovered. The Germans introduced fake British £5, £10, £20, and £50 notes into circulation in 1943: the Bank of England never found them.

In August 1945, Soviet Special Camp No. 7 was moved to the area of the former concentration camp. Nazi functionaries were held in the camp, as were political prisoners and inmates sentenced by the Soviet Military Tribunal. By 1948, Sachsenhausen, now renamed “Special Camp No. 1”, was the largest of three special camps in the Soviet Occupation Zone. The 60,000 people interned over five years included 6,000 German officers transferred from Western Allied camps. Others were Nazi functionaries, anti-Communists, and Russians, including Nazi collaborators and soldiers who contracted sexually transmitted diseases in Germany. By the closing of the camp in the spring of 1950, at least 12,000 had died of malnutrition and disease.

In 1956, the East German government established the site as a national memorial, which was inaugurated on April 22, 1961. The plans involved the removal of most of the original buildings and the construction of an obelisk, statue, and meeting area reflecting the outlook of the then government. The role of political resistance was emphasized over that of other groups.

At present, the site of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp is open to the public as a museum and a memorial. Several buildings and structures survive or have been reconstructed, including guard towers, the camp entrance, crematoriums, and the camp barracks.

Following the discovery in 1990 of mass graves from the Soviet period, a separate museum has been opened documenting the camp’s Soviet-era history.

Sources: The Forgotten Camps.

Encyclopedia of the Holocaust - Sachsenhausen.

Wikipedia - Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Scrapbookpages - Gas Chamber at Station Z execution site.