Nicole Kidman sleeps badly. Recently she got up at 3am to Google that thing, with the leg, where, “It feels like it needs to move?” But more often she will lie there in the dark beside her husband, in her Nashville bed, their two daughters sleeping some rooms away, and make decisions. She will “contemplate”. Between midnight and seven, she says, coolly, is the most “confronting time”.

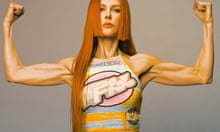

It says a lot about Kidman, her prolific career, her sustained presence on film and glossy TV, that we can immediately picture her there, hair coiled on a pillow, eyes wide, the restless sense she has become claustrophobic in her own body. Kidman, 54, has been acting since she was 14, already 5ft 9in then, with skin that burned easily. She started in theatre partly as a way to get out of the Australian sun – a year later she was known locally (she told an early interviewer) for playing “older, sexually frustrated women”. Over the next 40 years she extended that repertoire, so now she is known for playing cryptic, adventurous, troubled women, too, in brave work that might not have been made were it not for her glittering star-power.

We were meant to be meeting in London, but the slipperiness of the pandemic meant a last-minute “pivot”, she says (“I must stop using that word!”), so Kidman greets me from New York in a pinstriped shirt and Zoom window labelled “Nic”. She is here to talk about Being the Ricardos, Aaron Sorkin’s new Oscar-tipped biopic about the relationship between I Love Lucy stars Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. So it’s there we start, listing its themes with a certain glee: ideas of home, family, marriage, of power and how gender complicates that, of motherhood. “Well that’s just it,” she says. “That’s my whole life. I love that you can describe the film, and then it correlates to my life. Isn’t that fantastic?”

The film takes place across one fraught week in the 1950s at the height of the “queen of comedy’s” fame, when Ball and Arnaz (played by Javier Bardem) are juggling the professional implications of a new pregnancy, accusations of communism and allegations of infidelity that eventually lead to divorce. “It’s about a creative and romantic relationship that doesn’t work out. But from it come some extraordinary things. And I love that. I love that it’s not a happy ending.” She takes a swig from a large bottle of water that, at first glance, appears to be wine. “This film says you can make an extraordinary relationship thrive and leave remnants of it that exist forever. Yeah, that’s really gorgeous. You can’t make people behave how you want them to, and sometimes you’re going to fall in love with someone who isn’t going to be the person you spend the rest of your life with. And I think that’s all very relatable. You may have kids with them. You may not, but they were very much in love.” We pause. Is this, I ask with exquisite care, your way of talking about Tom Cruise? She chokes, just a little. “Oh, my God, no, no. Absolutely not. No. I mean, that’s, honestly, so long ago that that isn’t in this equation. So no.” She is angry. “And I would ask not to be pigeonholed that way, either. It feels to me almost sexist, because I’m not sure anyone would say that to a man. And at some point, you go, ‘Give me my life. In its own right.’”

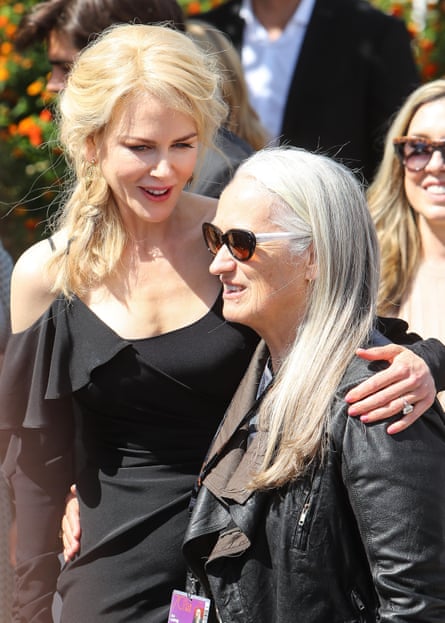

It is a more than fair point. Though the two were married (and adopted two children) she has had at least two whole lives since their split, a year after the 1999 release of Eyes Wide Shut, the psychosexual drama they made with Stanley Kubrick. A decade of bold films followed, including Moulin Rouge and The Hours, for which she won a best actress Oscar. In 2006, she married country music star Keith Urban and she still dissolves a little at the mention of his name. “We say to each other,” she smiles: “‘You’re enough’.” But when she reached her 40s and gave birth to a daughter, she found the industry suddenly less hospitable. She decided to politely retire. To, “have my baby and sit on a farm. Until my mum said to me, ‘I don’t think you should just give up.’ I was quite convinced I could grow vegetables and be at home and be very satisfied with that, but was pushed quite substantially by my mum. Friends, too – I have friendships that have permeated my life.” She’s known Jane Campion, who directed her in The Portrait of a Lady and Top of the Lake, since she was 14. “Those relationships are relevant. They’re the threads that pull you through, when people show up and go, ‘I know you and I believe in you’, and push you forward.” Her life and career choices, like the decision to set up her own production company as a response to an ageist industry, are, “Not always coming from a sense of confidence, like I know what I’m doing. Not at all. A lot of times I’m relying heavily on the people around to say, ‘You’ve got more in you.’”

And then, after a fourth child (using a surrogate), came another life, where alongside a series of blockbusters and twisted indie films she carved out a career in “prestige” television, the kinds of glamorous programmes (like The Undoing and Nine Perfect Strangers) that we watched without once looking down at our phones. Critics said she was making her best work yet. That her midlife career renaissance was not just good for her, but good for women everywhere. She was surprised. “I would never have thought television would be an avenue for growth for me.”

The breakthrough was Big Little Lies, which she produced with an old friend, Reese Witherspoon, and won an Emmy for her portrayal of Celeste, whose poise and perfection masked violent abuse. “Television gives you a much stronger connection with an audience, because you’re in their homes. I had a far deeper response than I’d ever had, which just suddenly came hurtling towards me.” People would approach her to talk about, she says in quote marks, “A ‘friend’” in a similar situation to Celeste. “It was… quite lovely.”

The last time she remembers her work resonating like that was with the film Lion – she was nominated for an Oscar for her portrayal of the adoptive mother of a boy searching for his biological family. “It was a very disarming thing. My sister sat next to me during a screening, a dark theatre, just the two of us, and she was wrecked. She was just… destroyed by it.” Which Kidman loved. “The idea of penetrating people, so their guards come down, is beautiful.” She smiles. “Then the way we reach out and help, hold each other’s hands. Which has been taken from us recently, hasn’t it? There’s something incredibly beautiful about being held. About feeling safe.” Her face suddenly shifts. “Sorry. It just makes me cry that we’ve had that taken away. People in hospitals not being able to be held in their final moments. I… can’t take it.”

Does she cry often? “Yes.” What was the last thing that made her cry? “That’s too personal,” she smiles. “But yeah, I cry. I try to keep a lid on that, but everything is deeply sad. There’s a huge melancholia, right? I mean, when you really study melancholy people, we’re very present. I have an enormous amount of that. I think a lot of people walk around with it too, don’t you?”

Her family are flying to Australia for Christmas, to see her 81-year-old mother who was widowed when Kidman’s beloved father, a psychologist, died in 2014. “Today I was looking at my phone, and you know how they have those memory things, where they show you random photos? I looked and then, his face was there…” She shakes her head, startled by grief.

I want more on her family, on life with two young daughters, but with a gentle apology she dismisses my questions. “No, I have to really protect them. I’ve learned to keep my mouth shut.” A Hollywood grin. I grudgingly respect her boundaries, I say. “Thank you. They’re something I’ve struggled with in the past.” Is it difficult knowing what to give and what to keep? “Yes, which is why I have the work. To speak through. But also,” she pauses, and considers how much to share, “I’m ‘in life’ right now.” She leans forward, her face suddenly filling the screen. “I’m not coasting along. I’m in it.” She is raising a 10-year-old and a 13-year-old, she is caring for her elderly mother, working solidly through the pandemic and, also, being a movie star. “That term confuses me. Can you define it? It’s too cerebral for me. I can only go to what Stanley Kubrick would say to me, which was, ‘Nicole, you’re a character actress.’ Usually, I’m resistant to labels. There’s a new generation now, saying, ‘No, you don’t get to define me just this way.’ I’m hugely supportive of this. And you can also change. I love that.”

How does fame impact her life? “Why are you so interested in the famous thing?” she asks, a little irritably. Well, I stutter, because you seem to be a real person – “Oh my God!” – and yet also a star. OK. She nods. “I don’t live that life. I’m deeply embedded in a family, in a very deep marriage. I’m parenting children. I’m a daughter. Those are the primary things. And yes, I have other things that circulate. But at my base are relationships that are very, to use your word, ‘real’.” She chuckles stagily. “And I’d love to have them be more rose coloured and fluffy, but they’re startlingly real, as is mortality, as are all of those things that you circle as a human being. The only thing I can bring to my work is that emotional truth. My life is my life – I’m left alone with that ultimately, right? I mean, you’re not working at 3am, lying in bed.” There is a brief pause, in which I visualise her pillow, possibly silk. She sleeps badly. The leg. The contemplation. The phone memories unbidden. “I’m in the midst of it, a woman in her 50s, with a whole lot of things, circling.” She is prepared to use some of these things, these vulnerabilities, to bring them to her work, “But not all of them. Because that’s not fair. To me. To my relationships. I can give a portion of it, really deeply. But I have to do it in a very safe place with people that I trust not to abuse it or hurt me. And we’re going to value it.”

I’m interested in Kidman’s fame not just because of the dissonance between that inscrutable celebrity and the mischievous mum I meet today, but because her stardom is of the extreme kind. Never for her the Ugg-booted Starbucks run, the candid Instagram posts, even the casual political affiliations. Her wild and glittering fame, I realise, is not in spite of an audience never quite knowing her, it is because of it. Her 40-year career seems to have taught her the importance of staying a stranger to your audience, who need that distance – not just the length of a cinema or barrier of a screen, but the psychic separation – to maintain the dream and the desire, the belief that she can, over the course of a single popcorned day, be a witch, a courtesan, Lucille Ball and a gaslit Manhattan therapist with a very nice coat.

One warm afternoon she was at the Cannes Film Festival chatting to Meryl Streep when the conversation turned inevitably to work, and the lack of opportunities for women. “Directors, writers, crew-members – the figures were astounding.” They paused, and I imagine them languidly nursing their sparkling waters before making a pact. “There was a lot of talk about how things were changing. But then I was like, ‘We’ve actually got to do something.’”

Kidman pledged to star in a female-directed film or show every 18 months. She has exceeded that. “It was my way of going, ‘Hold me accountable.’” Success, she’s clear, comes with responsibility. “My commitment to this industry is that I will give a platform for new voices to come forward and they can piggyback on me… That’s part of the ‘paying it forward’.” What this looks like is a lot more Kidman on screen, and riskier work, and presumably a pay-cut, too. “I could rest. Or I could actually do what I promised I’d do. Sure, I’m tired. But at the same time, I feel this strong sense that I need to stop talking about it, and actually… do it.” There’s a further motivation, too. “I have a 13 year old who wants to be a director – she’s really interested in comedy.” She opens her eyes very wide, as if to say, “Imagine!”

As a child, her feminist mother would take her to meetings of the Women’s Electoral Lobby. “A hundred women, sitting around talking and smoking. I can’t remember the actual conversations, but I remember eating a lot of biscuits.” The truest feminist act. It’s these meetings I think of when she tells me her dream of building a kind of studio. “Creating a real home for 10 or 15 women, all working out of one little area, supported completely. I’d love to be able to get things made without having to actually be in them, to just generate it without having to actually put my own body on screen.” I’m surprised to hear she doesn’t have that power. “Not yet.” She sits up even taller, her chin raised like battle is near.

As they completed Being the Ricardos, Kidman approached Aaron Sorkin with a question. “I said, ‘The first time I see the film, I want to do it with an audience.’ He was like, ‘Are you insane?’ But I couldn’t bear the idea of sitting in a dark room and watching myself playing Lucille Ball going, ‘I’m dreadful.’” So, tentatively, Sorkin took her to a screening, where she sat in a state of clenched torture as the lights went down. And then? “Then I heard people laugh. And it was so good.”

Known for the grace she brings to serious roles, she’d tried to pull out of the film at least once, scared that she wasn’t the right person to play an iconic comedy star. But then she started crushing grapes. On set as Lucille, she tucked her skirt into a belt and lowered herself barefoot into a vat of grapes, and, her mouth a lipsticked grimace, she crushed them into wine. “It was so freeing! The abandonment – it was wonderful. I didn’t want to give that up. I can do that grape sequence to a tee, but I only got to do it three times.” She’s leaning into the camera again, her eyes round, deadly serious about the transportive joy of clowning. “I kept asking Aaron, ‘Can I do it again?’” A heavy smile. “Can I do it again?”

Being the Ricardos is now in select cinemas and on Amazon Prime Video