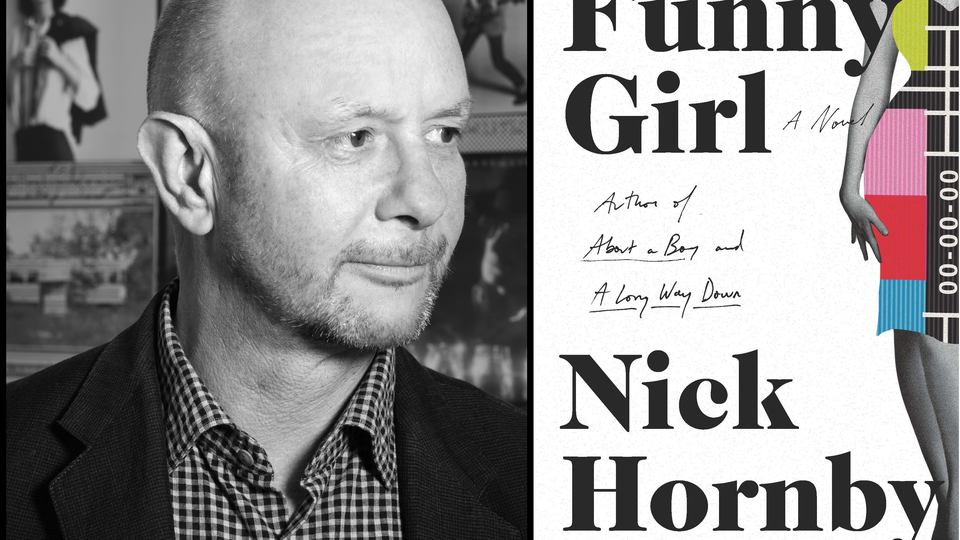

How Nick Hornby Keeps His Writing Fresh

The author of Funny Girl, Fever Pitch, and High Fidelity champions the virtue in adapting other people's work and explains why he never wants to write a sequel.

Nick Hornby’s new novel, Funny Girl, begins in 1964, around the time the 1960s are really starting to become The Sixties. His heroine, a small-town beauty queen named Barbara, goes through a transformation of her own: She moves to the city, renames herself Sophie Straw, and lands the starring role on an edgy new sitcom. The glamor of London is all around her—rock stars, nightclubs, the West End premiere of Hair—but she spends most of her time in a BBC studio, trying to make the kind of show that’s never been made before.

More than 20 years into his own career, Hornby has had plenty of time to reflect on the nature of creativity and fame. He’s written 10 books and watched several of them get adapted for the screen (as well as for television and Broadway). He’s also adapted other authors’ work, writing the screenplays for the Oscar-nominated films An Education and Wild.

All of this experience shows through in Funny Girl. As his characters collaborate on their sitcom, each of them entertains a different vision of success. One wants to be a mainstream celebrity, another wants to be a subversive artist, and a third just wants to support his family. But they all grapple with the same basic question: When you’re creating something wonderful, how do you keep it going forever?

I spoke with Hornby by phone about Funny Girl and Wild, as well as British comedy, aging rock stars, and what inspires a writer to keep on writing.

Jennie Rothenberg Gritz: Most of Funny Girl takes place during the same time period covered in Mad Men. How would you say that era was different in England than in America?

Nick Hornby: I think the hippie thing didn’t happen quite so much over here. And also, the ’60s in the U.S. were quite a violent time. I think here it was more of a long-postponed celebration of the end of the war, the Beatles obviously being a big part of that.

Gritz: While you were working on the novel, you read David Kynaston’s books about midcentury Britain. Did you have any revelations while reading them?

Hornby: When one gets older, you just realize how close in time everything was. The memories were so fresh for all the people who brought me up. My parents had experienced, I suppose, quite severe privations. My mum was evacuated. My dad lost his dad. We were all still feeling the effects. We had food rationing till the mid-1950s, so just a couple of years before I was born. A lot of the place was still being rebuilt. It was a very dark, austere time. And I realize now that the end of the Second World War to my birth was just 12 years. Well, that’s 2003! It’s so recent.

There were some incredible details as well. For example, TV shut down for an hour every evening between 6 and 7 p.m. so parents could put children to bed. There was that kind of paternalism of the BBC: Parents are putting their children to bed now, and we’re going to help them.

Gritz: What was television actually like there before 1964? When Americans think of British comedies, we tend to think of later ones like Monty Python and The Office.

Hornby: There was a lot more stereotyping back then, much gentler humor. There were domestic scenes where people played incredibly traditional roles—women spending too much of their husbands’ money, for instance. It was what we call a kind of seaside humor. It was never crude in an edgy way, but there was kind of an obsession with toilets, lots of that sort of thing. Looking at it now, it’s hard to see where they were even expecting the laughs to come from. Then along came these writers who were more working class, more leftwing, probably quite male, but a lot sharper than the previous generation.

Gritz: Why does Sophie, a girl from a seaside town in England, idolize Lucille Ball?

Hornby: I think she’s the most obvious female role model for someone who wanted to be funny and on TV in the 1960s. It’s always that thing—who is that person who makes you believe what you want to do is possible as a job? Not just a teacher telling you you’re clever.

Gritz: It sounds like you’re speaking from experience. Who was that person for you?

Hornby: There were authors I read as an adult who completely inspired me. But when I was a teenager, I got to hang out with Tom Stoppard for a bit. My mum was his wife’s secretary. He was obviously super smart, but he was also approachable and normal. I think he was the first person I’d ever met who I’d thought, “Oh, I see. There’s a living in this.”

Gritz: In Funny Girl, each of the main characters has a very different vision of success. Are these all perspectives you’ve had at one time or another?

Hornby: Yes. Probably pretty much on a daily basis. When you work on your own and you have too much time to yourself, I think you can adopt lots of different perspectives in a couple of hours.

Gritz: Just like in “Working Day,” that song you wrote with Ben Folds.

Hornby: Yes, that’s right! You know too much.

Gritz: I can see how your outlook can fluctuate over the course of a day. But it must have also changed in bigger ways over the course of your career. It’s hard to imagine you feeling the same way about fame back in the High Fidelity days.

Hornby: You know, it’s interesting. When I wrote High Fidelity, never in a million years would I have thought from point of view of the artist. I didn’t feel I was one. I was a fan and wrote a book about being a fan.

Gritz: What have you learned isn't the goal of being a successful artist?

Hornby: For instance, when people talk about things like the red carpet for movie premieres. They say, “Oh, God, you’re going to get to go on red carpet!” I was doing it recently for Wild. You walk down this red carpet, quite possibly in the pouring rain. You have to shuffle down the line and talk to endless people with cameras pointing at you who actually are more interested in talking to someone behind you. Of course, it’s different if you’re Reese Witherspoon. People actually want to talk to her. But there’s no fun in it for Reese, either. There’s no possibility of fun on a red carpet! It’s completely ridiculous.

That’s pretty much a symbol of the whole thing. Once you realize that, everything else starts to fall away, and all you’re left with is the work.

Gritz: How do you deal with the pressure to always keep things fresh and original? That’s a major theme in Funny Girl.

Hornby: I always naturally want to change things up if I possibly can. I never want to write a sequel to a book. I don’t want to go back over things. I don’t want to adapt my own books for the screen. That’s something that’s important to me, the keeping it fresh.

A lot of what Funny Girl is about for me is the experience feeling very happy doing a certain thing with a certain group of people. That partly came about because of having really positive experiences writing movies. Even though I do the writing on my own, I’ve worked with directors and producers. There’s that sense of clever people sitting in room coming up with ideas, taking entertainment incredibly seriously. That’s something I find really thrilling. When it turns out right, you think, “I just want to do something different with exactly the same people.”

But creating something different will necessitate that the experience not be the same. It’s like standing on a ball. You can do it for a couple of minutes. Then you have to fall off and get back on again in a completely different position. There’s a kind of sadness to it, but you can’t keep doing it. I was thinking particularly when writing the book about John Lennon and Paul McCartney. There’s a part of everybody that wanted them to keep writing songs together forever.

Gritz: I saw Crosby, Stills, and Nash last summer. Nobody wanted to hear their new songs and they knew it. At one point, David Crosby sort of apologized and said he knows everyone just wants them to stop writing new stuff, but they don’t want to stop. It makes you wonder if that’s admirable, or if they should just stick to their old hits from 50 years ago.

Hornby: One thing with music, I think, is that it’s very hard for us to tell whether these new songs are as good. We are invested in their ’60s and ’70s selves. The other thing is that when you got to know Crosby, Stills, and Nash, you probably only owned a few albums of theirs. You played the same songs over and over again, and that’s how you got to love them. Now you own 15,000 songs, and if you don’t like one after 15 seconds, you change it.

Gritz: Unlike most people over 35, you actually like discovering new music. But does it really affect you as deeply as the music you loved when you were younger?

Hornby: That’s the thing about being in your teens. It’s like being a completely blank piece of paper and then people start writing on you—filmmakers, musicians, writers. My God, I didn’t know about this, I didn’t know about this! You get to a certain point in life where you’ve been scribbled all over. There’s hardly any room left. Every now and again, someone comes along and can just about find a corner to write their name in small letters.

Gritz: What’s that experience like on the other side, as a creator of art rather than a consumer? You’ve filled a lot of pieces of paper. What keeps you wanting to write more?

Hornby: I just always feel that I haven’t done the thing that I want to do. I don’t know what the thing is. I just know it didn’t go quite right the last time.

Gritz: The movie Wild was pretty different from anything else you’d done before, mostly because it’s so American. The emotions are so direct—there’s nothing understated or oblique about them. And there’s that American idea of going out into the wilderness to conquer yourself. How were you able to get into that mindset, beyond just reading Cheryl Strayed’s memoir?

Hornby: I guess the book spoke to a part of me that I haven’t been able to use much in my own books or in other screenplays. There’s a side of me that responds very deeply to American things. When I first read a review of Wild, I thought it sounded great. And after I read it, I chased after people to let me try and adapt it.

The book to me felt like a Springsteen album. I always loved Springsteen, but he’s very American. That kind of directness is really interesting to me because it doesn’t have to be unsubtle. It’s just a different way of being, a different way of thinking. The great thing about adaptation is it gives you a chance to be someone else. However inventive you are, you still come up against the limits of your own voice and your own imagination. When I started to write the screenplay for Wild, it felt like a personal response. I knew how to do it. But as you say, it wasn’t me.

Gritz: I know you hate it when reviewers give directors credit for things that are in the screenplay. I read a review the other day that gave director Jean-Marc Vallée the credit for the ending of Wild. How did you decide to have Reese Witherspoon speak out the final paragraph of the book?

Hornby: Actually, the director did that! Ha! He wanted to end it with the lines from the book. I had a different ending in mind. But you know, when it’s an adaptation, it’s not your story. So it’s a different kind of negotiation than it is for an original screenplay. And I do think the ending worked well.

Gritz: Speaking of endings, the last few scenes of Funny Girl take place in the present day. All the characters are old and past their prime, but they still have that need to create. What made you decide to end it that way instead of leaving them at the pinnacle of their careers?

Hornby: I suppose it all came of a piece. When I first thought about the book, I realized I wanted to write about the characters old in the present day. Which meant setting the peak of their careers back in the past and going back to describe it.

Gritz: So you were always sort of looking at their 1960s selves through the eyes of their older selves.

Hornby: Yes. And I suppose that writing it, that knowledge of what was to come made it easier for me to feel poignancy about their younger selves. I always wrote knowing that that time in their lives wouldn’t be able to stay.

Gritz: You do a great job of making their reunion show look totally ridiculous. But they’re still so excited just to be creating something again.

Hornby: That’s the conclusion I’ve come to. You can’t really ask for anything more than to be working for your entire life—and to be doing something that some people respond to.