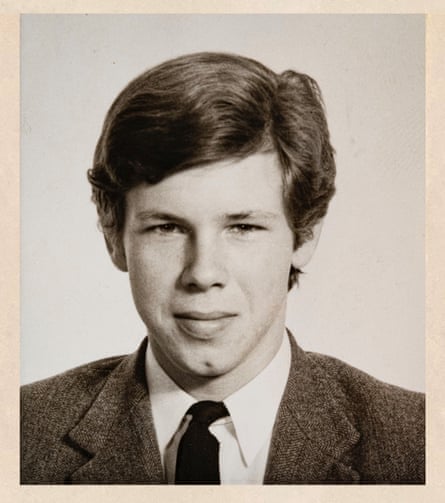

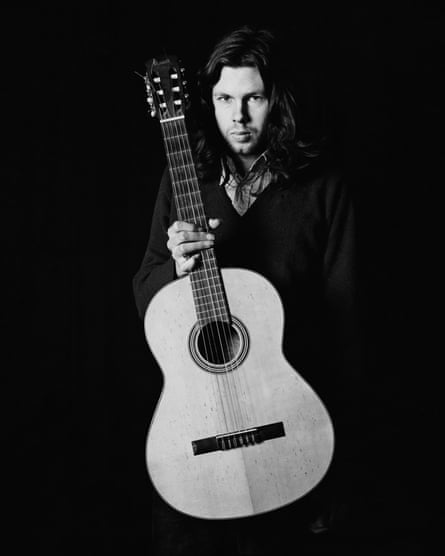

For a singer-songwriter who only made three albums, Nick Drake continues to cast a long shadow. A mixture of extreme shyness and difficulties with mental health meant that his beautiful, meditative and deeply melancholic take on mystical English folk slipped through the commercial cracks during his lifetime. There is no known footage of him performing live and very few interviews exist. Drake died from an overdose of antidepressants in 1974, aged just 26, but since his death, his music has found new audiences as successive generations have discovered an enigmatic but immaculate body of work.

Now a new biography of Drake, by the writer Richard Morton Jack, offers a definitive version of a life story previously shrouded in mystery and, eventually, clouded by tragedy. Containing unseen photos, previously unreleased correspondence and the insights of the people who knew Drake best, it provides a rounded portrait of an artist whose recorded works continue to beguile and resonate. In these exclusive extracts, we see the light and shade of Drake: his problems are laid bare, but so is his exquisite artistry. Phil Harrison

While Drake’s career as a musician was characterised by diffidence, his youth wasn’t entirely devoid of high jinks. A road trip with some friends to north Africa, for example, saw a memorable encounter with some of his musical heroes

Rumours were swirling around Tangier that the Rolling Stones were in town. [His friend] Julian [Raby] confirmed their presence on the penultimate night: “I was looking out of a tiny window over a narrow alley when I saw the Stones’ party passing, in sheepskins and bell-bottoms, like a medieval apparition.” Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brian Jones were there, as well as a court including Anita Pallenberg, Cecil Beaton, Robert Fraser, Christopher Gibbs and Michael Cooper. Urged by his companions, Nick took his guitar when they sallied forth the next evening. “Hoping to make contact with them, we went down to their hotel, the celebrated El Minzah,” he wrote home.

“Having seen them going in, looking quite extraordinary even by their own standards, we marched in and I made a request to play in the bar. After I had been turned down very politely, Bob [Drake’s friend Rick Charkin, so nicknamed because he was thought to resemble Bob Dylan], whose nerves seem to stop at nothing, proceeded to ring up the Stones’ suite and ask if they might be wanting a little musical entertainment! This was unfortunately refused in a similar fashion, and it was decided that my fortune should be made elsewhere. So we made a quick tour of the nightclubs, asking if I could play.

“Fortunately, one of those which accepted the offer was the Koutoubia Palace, Tangier’s most exclusive nightspot, which is done up in the style of a Moorish palace. I couldn’t help feeling a little out of place, but all the same I played for about quarter of an hour. The reception was extraordinarily good and we all got stood rounds of drinks, which was rather pleasant.”

It’s notable that – albeit egged on by his friends – Nick had the confidence to perform spontaneously. The following morning Mike [Hill, usually the driver on the trip] whisked them the 370 miles to Marrakech. He was overwhelmed by its souk, calling it “a huge, crowded gathering place where one finds musicians, magicians, soothsayers, acrobats, snake-charmers, dancers, and various other oddities which I am unable to find a name for. Best of all was a set of African drummers and dancers, who produced about the most infectious rhythms I have ever been infected by.”

By coincidence the Stones were also in the crowd, making a field recording. The friends revived the idea of getting Nick to play for them. Having established that they were staying in an old French colonial hotel, La Mamounia, they went there that evening. Upon discovering that they were in its grand dining room, says Julian, “Rick went in with Nick and told them how great Nick was at the guitar. Nick then played for them.” It’s striking that Nick was willing to perform alone and at close quarters in front of such an intimidating audience. Rick does not recall what he played, but when he stopped, continues Julian:

“We all sat down. It was a large room with a long table immediately on the left, deserted but for the Stones and their entourage. Mick Jagger was at the head, and in my memory Nick sat at the opposite end. It was like a scene from The Decameron, with food everywhere, which they invited us to help ourselves to. We were very grateful, because we were starving. They were bombed out of their minds yet clearly impressed by Nick. At the end of the encounter Mick said to him: ‘You must come and see us when you’re back in London,’ which I doubt he said to everyone.”

Young musicians all over the world would have envied Nick, yet by Julian’s account, “He was so congenitally mellow that it seemed normal for him. He seemed to internalise it all.” His own vague account to his parents ran: “I went in and did them a few numbers. We in fact got quite chatty with them, and it was quite interesting learning all the inside stories.”

An exchange of letters between Drake and his father, Rodney, during Nick’s university years hints at his growing turmoil and confusion. His father’s reply is patient and kind but provides a sadly prophetic foreshadowing of the problems that were to undermine Drake’s musical career and overtake his life

Nick wrote to his parents on Thursday 23 January 1969.

“Cambridge has been quite pleasant this term, but here I am, becoming increasingly sure that I want to leave soon. I’m sure that our various conversations have made clear my general feelings … As far as performing is concerned, I am certainly no more than amateur. However, with regard to my songwriting, I can only progress from the stage that I have reached so far by developing a purely professional approach … I know for a certainty that I must make this progression with my music in order to achieve any sense of fulfilment.

“I hope you can perhaps appreciate that the idea of having my music as a ‘vacation hobby’ for another year-and-a-half is not a particularly happy one. It seems that Cambridge can really only delay me from doing what at the moment I most need to do.”

Having discussed the matter at length with [his wife] Molly, Rodney sent him a considered reply the following week. “Obviously it is a step which we have to consider carefully, because it is an irrevocable one,” he began, going on to pose two vital questions: “Are you more or less likely to succeed at your chosen career if you leave now? Secondly, what advantage unconnected with your career may you be throwing away if you leave now.”

after newsletter promotion

He continued candidly: “We are slow developers in our family and you, I believe, are no exception. I would go so far as to say that you will surprise yourself in the next two years by the changes and development that will occur in your personality, your understanding and your outlook. In addition to this, any career involving self-employment demands a high degree of self-discipline and a will to overcome one’s weaknesses, and making the effort required to tackle problems which do not come easily. I think you have a long way to go here.

“You believe that the problem of turning yourself from an amateur into a professional can be solved merely by transferring yourself from Cambridge to somewhere where you are surrounded by, and under the influence of, professionals in your chosen field. From what you say I take it that you must believe that it was the prospect of returning to Cambridge for eight-week periods during the year that prevented you, in the long summer vac, from getting into the swim, so to speak, and of starting to acquire the professionalism which you are rightly seeking.

“But I doubt this very much and I would regard as far more likely reasons your reticence (which you must overcome), your difficulty in communicating (which you must overcome), and your reluctance to plunge in and have a go (which you conceal from yourself by self-persuasion that more solo practising and solo listening are required before the move is made) … If I am right in what I say, and the real trouble is that you have not yet overcome your weaknesses (and God knows we all have them), then you may well find that you have thrown over Cambridge simply to continue indefinitely on the outskirts of what you are looking for.

“At Cambridge you have a chance to fight your weaknesses and overcome them (and fight like hell you MUST), to discipline yourself from inside, and take a more active interest in your fellows (another weakness of yours – I am being very blunt, aren’t I?) and generally to prepare and develop yourself to make a real success of what you want to do. And, in the meantime, your creative powers will be developing, not stagnating, do please believe me. On the second aspect – what advantages unconnected with your career may you be throwing away – there is not a great deal to say except that it is a rounded personality which is most likely to lead its owner on a happy and full road though life. To specialise too early and to have interest in only one activity makes Jack a very dull boy. One-and-a-half years may seem a long time to you. Allow me to assure you it is not – but it is a terribly important time in the development of you as a person into something that you are going to start to be at about the age of 23.

“The winning of a degree may seem to bear little significance to you, and the argument that it is a safety net if you come a cropper with your music will doubtless evoke the response that a safety net is just what you don’t want. I would say to you, however, that the self-discipline which it involves, apart from anything else at all, is a priceless asset in whatever you want to tackle during the rest of your life. So there we are, Nick – there’s my view. I urge you to resolve to see Cambridge through.”

It was indeed a blunt statement, but Nick knew it was written out of love, recognised the truth in it and did not take it amiss. Rodney had written nothing that any concerned parent wouldn’t have thought under the circumstances, but he and Molly perhaps didn’t grasp the intensity of their son’s commitment to his music or – as they later conceded – his brilliance.

Drake’s third and final album Pink Moon is a bleak, minimal affair, seemingly wrenched from the depths of mental illness. As shown by the reactions of his family and contemporaries, it’s a reflection of his brilliance and the uncomfortably intimate nature of the material

Nick’s relationship to the finished album is unknown, and it’s likely his family and friends were unaware of it until it was released. [His friend] Brian Wells is convinced Molly and Rodney didn’t listen to it closely, and Gabrielle [Drake, Nick’s sister] doesn’t recall doing so, either; by the time it appeared they were more focused on his day-to-day condition than on his musical output. Rodney later wrote that it was made “when Nick was getting pretty bad, and it’s rather ‘way out’, as they say”. In another letter he admitted: “The material on Pink Moon has always bewildered us a little (except From the Morning, which we love).”

Joe Boyd [who produced Drake’s first two albums] had nothing whatsoever to do with Pink Moon. The first he knew of it was when Island sent a copy to him in Los Angeles. “When I saw the cover I was horrified, and when I played it I was even more horrified. I interpreted its starkness as a rebuke to me. I thought it was self-destructive, a capitulation, as if he were saying: ‘Fuck it, I don’t care whether people listen to it or not.’ I listened to it once.”

Nick’s close friends were upset by it, too. Wells says: “I wasn’t around when he was making Pink Moon, and when I heard it I found it bleak. I remember a friend from Cambridge describing it as ‘music to commit suicide to’.” Alex Henderson and Ben Laycock were taken aback by it after Bryter Layter. “We found its atmosphere dark and depressing, knowing how Nick had become,” says Alex. “We had no idea what musical direction he would or could take after that.”

“I was appalled by Pink Moon,” remembers Drake’s university friend Paul Wheeler. “I found it incredibly upsetting. I thought the songs were frightening. To this day I cannot ever imagine listening to it for pleasure. It’s like opening some terrible Pandora’s box.”

Folk singer Beverley Martyn had similar concerns. “I thought: ‘This boy’s gone, we’ve lost him. We can’t reach him any more, and he can’t reach us.’ I wondered why he’d bothered to record some of the tracks, and who had thought it was a good idea to let him go into the studio and do so. They were so dark and sad, and telling about the state of his mind: doom, gloom and despair, with apocalyptic elements. People listen to it and say: ‘That’s a great line!’, and talk about the songs and the surreal cover like they’re a puzzle they can solve, but Pink Moon is like the Book of Revelation. It doesn’t make sense and it’s a manifestation of illness, of madness. When people are really ill they don’t know what they’re saying, they don’t hear what’s coming out of their own mouth. I thought those songs, those words were the product of a sick person.”

Musician Richard Thompson, who had collaborated with Drake, heard Pink Moon when [producer] John Wood played it to him in Sound Techniques: “I was disturbed. Part of what had made Nick’s earlier music so appealing was a balance between dark and light. The sadness inherent in the music had been veiled behind beautiful arrangements and an intriguing voice that drew you in. However, his third album seemed a stark cry for help, the voice of a man teetering on the edge of sanity.”

Not everyone felt that way. “I find it’s got some of the most optimistic songs of his,” said [arranger] Robert Kirby. “I think Pink Moon is in fact my favourite, as far as the songs are concerned.” Despite his disappointment at not having worked on it, he supported Nick’s prerogative in eschewing arrangements and later stated: “I think it’s his greatest work, by far.”

These are edited extracts from Nick Drake: The Life by Richard Morton Jack, published on 8 June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion