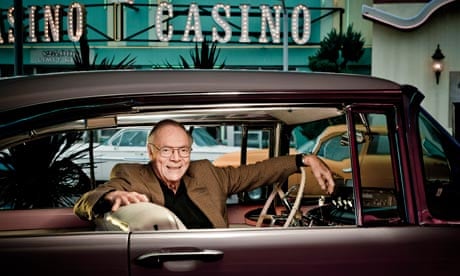

Nicholas Pileggi's office is at the back of a film lot in a suburb north of Hollywood. To reach it you walk along a low-rise strip out of 1960s Las Vegas where exuberantly finned Cadillacs are parked up at the roadside, and then past the blackjack and roulette tables of a cavernous casino, filled with all the chandeliered luxury of 50 years ago. The cast of the TV series Pileggi has conceived and co-written, Vegas, are out on location when I visit, so he is pretty much alone here, among the lovingly recreated props and vintage neon-lit backdrops of his own make-believe.

Pileggi's name often has the word "legendary" attached to it. Now a courteous and energetic 79, he was a legendary crime reporter in New York for more than 30 years, mostly writing inside stories about the mob, before one of those, the book-length Wiseguy, was picked up by Martin Scorsese and, with Pileggi's help, turned into the film Goodfellas. Pileggi then became a notable screenwriter, with credit for another Scorsese movie, Casino, among others. And during the time he was writing those films, he was also one half of a legendarily joyous Hollywood marriage, to Nora Ephron, fellow journalist and writer of Sleepless in Seattle and When Harry Met Sally.

Ephron died in June last year, having kept her leukaemia secret from all but her closest family for six years. In what turned out to be a collection of farewell essays, she closed by listing the things she would miss when she finally had to go. "My kids, Nick, spring, fall… Dinner at home just the two of us… Pride and Prejudice… Pie…" (She also listed those things she wouldn't mourn: "Dry skin, email, bras, funerals…")

Sitting behind his desk on the lot of Vegas, Pileggi wears the traces of those legends on his face. He is a deeply charming man, full of stories, and the kind of animated listener who could clearly get gangsters to open up to him, and stay on good enough terms to come back for more. He has a rich Italian-American New York voice, with some of the twang of the wiseguys he documented – his parents were first-generation immigrants from Calabria, just across the water from Sicily. And he carries about him too just a hint of the distracted wildness of his grief. He is careful, when we talk, not to reveal too much of that. Though whenever I mention Ephron's name in the conversation that follows, his eyes fill up a little and his voice struggles briefly to hold its easy composure. Writing Vegas has been his lifeline in the past six months, he says.

"To say the only antidote to grief is work is one of the oldest cliches," he suggests. "But cliches are right sometimes. Work takes your mind in a direction you might not otherwise go. Loss is loss, it doesn't change that fact. But being involved in creating 22 episodes of a television show, with six people in a writers' room – you have to say it's a help."

It's given him some structure?

"Well, I'd have some structure too I suppose if I was doing journalism or working on a book," he says. "But I'd be doing it alone. And I've already got far too much alone."

Ephron, he says, was very excited about Vegas. In the weeks before she died they had gone to a promotional event thrown by CBS at Carnegie Hall in New York, announcing forthcoming highlights. "There was Vegas as big as life," Pileggi recalls, "and Nora leaned across to me in the theatre and said, 'This one is for real… you can't just phone it in.' She was very hopeful for it. This was in the spring. Nora was mad for the series The Good Wife, and the whole cast of that show was there too, and she gushed over them because she really wanted to hire Julianna Margulies for her own next movie."

So, at that point, they didn't know how much time they had left together?

"Well," he says, "you know you have some time. You are always hoping."

Among the unusually sincere outpouring of love that attended news of Ephron's death in America, several friends and commentators noted the perfect symmetry of their relationship, like one of Ephron's romantic comedies: "Together they lived up to every lush movie score and snappy line that Hollywood could devise," a writer friend observed in the New York Times, "more glamorous than even the he-and-she of The Thin Man. Nora understood the need for a twist, so of course in their partnership, Nick, the Calabrian who hung out with made men, capos and squealers, was the softie; Nora, a Wellesley graduate in an apron and capri pants, was the killer…" The pair of them were each other's best critics and sounding boards. Pileggi once noted that they were both "thick-skinned enough to swap some very blunt criticism without fomenting marital strife". It must be terribly strange not to have her reading things, I say.

He pauses for a long moment. "It really is," he says eventually.

If Pileggi finds solace anywhere it is in stories, and he has a compelling one in Vegas, which he came across first when he was researching Casino for Scorsese. "I had done a book on the Casino story alongside the movie," he says. "That was mostly set in the 70s and 80s, but as a result of that research, as you do, I found out that the 60s was probably the more fascinating era. I kept wanting to go back to it."

Having held that thought in the back of his mind for 25 years, Pileggi has eventually found a way to write it. He describes the process with the excitement of a eureka moment. "In 1959 and 1960 Las Vegas was still really a western town," he explains. "It was cowboys, and it was also about the time when the mob decided they could come in." There were political reasons for that – a clampdown on illegal gambling in every state except Nevada – and there were engineering reasons; the rise of air travel, and the air-conditioning technology that allowed a casino to be kept cool in the desert. "And here it was – the fedoras were starting to come in against the cowboy hats."

Pileggi knew exactly the point at which those two venerable movie genres met. "This guy Ralph Lamb was the sheriff in Vegas during the 60s. He was a cowboy on a horse, and suddenly faced with the arrival of all these mafiosi. It was John Wayne versus Edward G Robinson!"

To begin with, Lamb wouldn't speak to Pileggi about this history, but the writer has learned persistence from dealing with gangsters, and eventually the sheriff was persuaded to be involved. "He had great stories. Part of the reason he was so good is that he wasn't narcissistic. He could take it or leave it. And now I think he has gotten to like it… He bonded very well with Dennis Quaid, who plays him in the show. But then which old man wouldn't like his younger self to be played by Dennis?"

Pileggi had always thought of the story as a movie, but could not get it to work in three acts. A TV series gives him more scope. "It allows it to become what it is: a saga," he says. He is a fairly recent convert to the idea of the box-set series. "Jacob [Ephron's son from a previous marriage] kept yelling at Nora and I that we hadn't seen The Wire," he recalls. "So eventually he just got us The Wire and he sat us down in front of it and he made us watch it. And of course after a night or two, Nora and I would be starting early and we'd get to 11.30 and say, well, it's only 11.30, let's watch another one. We'd be doing four or five in a sitting. Here was a new art form! And the shows that have come along since have carried that on – Homeland, The Good Wife…"

To attempt storytelling on such a grand scale Pileggi had to excavate hard into the facts of the genesis of Las Vegas. "I am a journalist at heart," he says. "I have no imagination. When you are free from a story that happened it has the freedom to go anywhere and I am no good out there in Nabokov-land..."

What he has always been good at is making connections. He had to start early, and old habits die hard. "When I began writing about the mob in New York," he says, "the story was still pretty much unknown; now we know more about those families than we do the boy scouts. Back then it wasn't the case. But if you grew up in one of those neighbourhoods, as I did, you knew who all these guys were."

Pileggi's father was a musician who played slide trombone in a cinema orchestra for silent films. Subsequently he owned shoe stores. "He had no direct dealings with the mob I don't think but he knew those guys," Pileggi says. "They used to call the neighbourhood 'the artichoke'. They kept it very tight. Everything inside the artichoke was home base, everything outside was prey. Because I knew some of them and I would talk to them, they would tell you things about the other crew, and then I would talk to the other crew. I became early on a transmitter of gossip."

He was careful what he said to whom, and he approached the reporting like an anthropologist. "I began by amassing a great deal of data. Every time one of these guys was arrested I made a card file for each of the people who was named in the trial. I ended up with thousands of cards. All colour coded – if there was a murder involved it was a red card and so on." Pileggi still has his archive. "When I was working for New York magazine in the 60s there was a story from the FBI that the mob had infiltrated conventional businesses in New York for the first time. I already knew of 500 businesses [that had been infiltrated], so I just typed up what I knew. I had a big scoop, everyone went crazy."

There must have been times when he had to tread a fine line?

"It was OK as long as I thought of myself like Margaret Mead on Samoa. I wasn't looking to put anyone in jail, I was interested in them as characters. Why did they do this stuff? And then of course, The Godfather came out and changed it all. The gangsters had always wanted to be in an opera, and suddenly they were. A more real world was the Goodfellas or Sopranos vision, kind of small town, but they loved the idea they were these Marlon Brando figures, of course they did."

It was in an effort to get that more brutally mundane version of mafia life on screen that Scorsese first called Pileggi, out of the blue. To begin with he didn't call back. "I didn't believe it when Marty left a message. I thought it was my friend David Denby, the film critic, winding me up. So I just ignored him. Eventually Martin called Nora and said, you know, maybe I could find time to give him a call, as he might have some work for me."

His success with Goodfellas followed his wife's with Heartburn (a dramatisation of her disastrous marriage to Watergate journalist Carl Bernstein) and When Harry Met Sally. They married in 1987, though they had known each other for longer. "I first knew Nora in the middle 60s," he recalls, "when she was working at the New York Post and then we worked on New York magazine together in 1968. I have a front page at home, 'How cops get away with murder' by me, and then across the top 'Nora Ephron on the Israeli war'. But of course we were both married at the time, and we were just friends, then in 1979 her marriage broke up and so did mine. And we connected again a few years later. It was always like we should have been together longer, but I guess that would have been a different story."

Ephron's mother, Phoebe, also a screenwriter, had famously instilled in her daughter a belief that "everything is copy" and Pileggi has long taken that maxim to heart himself. "I have six or seven other ideas on the go at the moment, beyond Vegas, there is always something," he says. I can't bring myself to ask directly if he thinks his grief has proved a creative force so instead we talk a little about the extraordinary tributes given to his wife by everyone from Meryl Streep to Frank Rich. "They were amazing," he says, "but they seemed very natural to me, knowing her."

Ephron once shared what she believed was the simple secret of happy endings in life: "marry an Italian". Pileggi is not going to disagree.

Vegas begins on 14 February at 10pm on Sky Atlantic HD

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion