The television is on in the corner of Lord Kinnock’s north London kitchen when I arrive, and who should be gazing out of the screen but Jeremy Corbyn. Kinnock bustles about making coffee, keeping one eye on the Labour leader while he laments the state of the garden and laughs about his wife Glenys’s terror of mice. He was woken at 6.45am by shrieks, and spent the first part of his day chasing a mouse with a tea towel. He will spend the evening with his two children and their spouses, watching Wales play Portugal in the semi-final of the Euros on TV, and sparkles with the same irrepressible bonhomie familiar from all our previous encounters. On this occasion, however, appearances are misleading.

“I’m bloody angry. Only anger is keeping me from falling into despair. It’s bloody appalling, the whole bloody thing is appalling. The referendum was won by falsehood and prejudice.”

Kinnock suffered two general election defeats as Labour leader, but 23 June was the worst of his lifetime. “Simply because everything else that’s ever happened that’s bad has been redeemable or reversible. This is of a different dimension.” He is angry with David Cameron for promptly resigning, because “it was the captain’s job to stay on the bridge. Just in terms of duty – straightforward duty.” But above all, he is angry with Corbyn. “People divide into those who are vain, and those who are not,” he observes, glancing over at the telly. “And Jeremy is a vain man.”

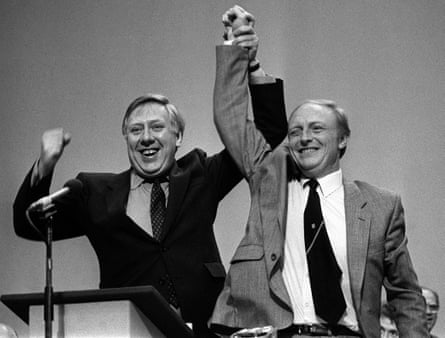

Kinnock was never a fan, and has made several critical public comments in the last nine months. “But I’ve been mostly quiet, despite many invitations not to be.” Now he is publicly calling for the leader to resign – and on Monday delivered a barnstorming speech to the parliamentary Labour party, so loud that reporters in neighbouring corridors could hear his roar. Has he ever before called for a Labour leader to stand down at a PLP meeting? He looks at me as if I must be mad. “Good god, no. The last time I heard it, it was Leo Abse making a lone voice call in the wake of the 1970 election for Harold Wilson to go.” This is, he says, a political crisis unlike anything he has ever seen before.

“I’ll tell you what happened,” he says about the meeting, from which the press was excluded. “The atmosphere was quite tense. There was real dissatisfaction that Jeremy wasn’t there. You know, if I had to fly back from India to get to a PLP meeting I would, and I think that’s true of most party leaders. But anyway, Jeremy wasn’t there.

“People made very candid statements. Not vicious; it was just very direct. Even people who had not voted for the no-confidence motion [last week] got up and said, ‘I’m now part of the 172 [who voted for it]’. One of the women MPs said: ‘It’s now 173. Then one of the men called across: ‘No, it’s 174.’”

Kinnock hadn’t planned to say anything. “I had absolutely no intention of speaking. My view was, this is for the MPs. But then Dennis Skinner spoke. And in my view gave an interpretation of history through which I lived that was seriously erratic. He said, ‘This PLP mustn’t think that it’s more important than the rest of the party.’ Well, the fact of the matter is, he’s been sitting in meetings since 1970, and he knows damn well that there’s never been the merest suggestion that a view should be taken because the PLP is more important. It’s taken because the PLP has a duty it can’t escape. It’s not about relative importance. And he knew that damn well. And I thought, ‘Wait a minute Dennis, you can’t get away with that’. It was at that point I put my hand up to speak.”

He remembers that he told his audience: “There has been a lot of talk about history. Well, let me say a little bit about history. We’ve been on the edge of the abyss before, but we’ve never been deep into it like this.” He said he would not allow the party he has belonged to for 60 years to split. “We are a democratic socialist parliamentary party, not content to be a banner-wagging social protest movement.” By the end, the former shadow minister Lucy Powell was in tears, and the audience on its feet in a standing ovation.

Corbyn, of course, has not resigned. A leadership challenge will unquestionably therefore be mounted, according to Kinnock – and as the last Labour leader to have faced such a challenge, he has a lot to say about the rules. That it was Corbyn and some of his current team who led Tony Benn’s 1988 leadership challenge against Kinnock is an irony upon which he does not dwell, perhaps for fear of looking motivated by bad blood. The point, he says, is that Corbyn and his team are now trying to break the party’s own rules.

The rule book clearly states, he insists, that in order to be a candidate, Corbyn would be obliged to secure the support of 20% of the PLP. Corbyn’s team insist that as the incumbent, his name would automatically go on to the ballot paper. If that were true, argues Kinnock, why did he himself have to secure nominations when challenged by Benn? And why did Corbyn’s own supporters call for a change to the rule in March, when they acknowledged that: “The current Labour party rules do not clearly spell out that an incumbent leader is automatically on the ballot paper for leader in the event of a challenger securing the requisite nominations”?

Unsurprisingly, lawyers have been consulted on both sides. Should Corbyn’s name get on to the ballot, Kinnock has an urgent message to everyone who wants to see a viable opposition in parliament. It comes when I ask if he wants people to join Labour in order to vote in the leadership election.

“Yes, definitely – and NOW! Labour supporters across Britain recognise that the 172-40 vote of no confidence in Jeremy Corbyn came from MPs who are constantly in touch with voters and dedicated to trying to make Labour electable. They have made it clear that he cannot give the leadership that is vital to gain credibility and national appeal for our party.

“All Labour people should therefore immediately join in order to be able to vote. I urge everyone who wants to strengthen Labour to do that. It is crucial if we are to gain leadership with the values, the quality and the broad appeal that’s needed to challenge and overcome the Tories.”

Corbyn’s supporters accuse his critics of exploiting the referendum defeat, so I ask if this was a coup waiting for an excuse. He hoots. “Well, if it was, they kept it secret from me! And I mix and mingle.” What precipitated the revolt was not the referendum per se, he says – although “the fact that Jeremy did 10 events in six weeks is pretty conclusive evidence that either he, or people influencing him, really didn’t want to put too much effort in.”

The catalyst, he says, was the sudden prospect of an imminent election. And despite Theresa May’s assurance that she would not call one, “I think the chemistry of politics, in the wake of her election, with a majority of a dozen, will say there are some arguments we’ve got to settle, Theresa, you cannot repeat the Gordon Brown experience, we must go now.” As his own MPs do not believe he could possibly win, “the idea that a party committed to the parliamentary route to socialism could be led by someone who doesn’t have at least substantial support in the parliamentary party is not taking itself or its mission seriously.”

I was a teenager when I first heard Kinnock making the case that Labour could only help the worst-off by winning power, and could only win power by appealing to the broader electorate. Did he expect to still have to make it now? “Good god, no.” He is not, however, surprised that it needs to be made once again under Corbyn.

“Deep conviction is entirely creditable. But dogmatic adherence to policy issues is not realistic. You can’t even bring up kids on that basis. I don’t think you can even buy a car on that basis. People of deep convictions can afford to compromise. People of shallow convictions are terrified of compromise, because they will consider that to compromise is to betray. Well, if you’ve got deep convictions, you know damn well it isn’t. You know that compromise is a means of getting to the next stage, a bit closer to what you originally wanted to do. It’s called parliamentary democracy.”

Corbyn’s supporters invoke democracy too, in defence of a leader democratically elected by the party only nine months ago. Kinnock is at pains to make no criticism of the hundreds of thousands of youngsters who joined the party to get Corbyn elected last year, and says: “I certainly welcome the vitality, energy, hope, optimism. Because I don’t think democratic socialism can run on an empty tank.”

Parallels have been drawn between Momentum and Militant Tendency, which Kinnock took on and defeated in the 80s, but he disagrees.

“No, those people were a threat to our democratic socialist character and priorities. Now, we’re in a different situation. These highly intelligent, very well-intentioned, principled people who joined en masse are smart young people. But a small number of people who are either long-lasting sectarians, or new to the sectarian game, saw the opportunity, and have not ceased since to try to manipulate them. And with some success.”

He doesn’t mean, he says quickly, that Momentum’s members are fools. “I feel the absolute opposite to any idea that the people who joined last year are simple-minded. The absolute opposite. But when people have had a lot of practice in helping to mould the opinions of people with great intentions – well, they’re pretty good at it; they’ve been doing it for decades.

“And when people who have had long practice in organisation and influence can produce phrases that appear to chime with your thinking, your hope and ambition for change in our society, then people will accept propositions that, if they sat down and thought about it, they often wouldn’t.”

He doesn’t believe dissident Labour MPs will break away and split the party. “I understand the argument for it, but they’d be wishing themselves into a different universe. Unless and until we have a government that will secure the enactment of proportional representation, people who talk about realignments are, in reality, talking about fragmentation.”

Nor does he foresee some broad, progressive parliamentary alliance. “Not because I’m tribalist, but because such a coalition, in order to be effective, would have to be very broad – and if it’s very broad, it’s by definition also very brittle.”

What, then, does Kinnock forsee? “If, in the immediate future, the feeling that parliament was no good for the advance of progressive ideas really took hold, it would be a crisis of a different dimension. No doubt about that. In the end, I don’t think it will. But the very small sectarian element in all this has inevitably moved from extra-parliamentary effort, to trying to mobilise anti-parliamentary effort. That’s what happens.”

I wonder whether the parallel to be drawn is not with the internal battles of the 80s, but with the international crisis of the 1930s. “If people recognise the causes and horrific consequences of that, I think we won’t descend into that abyss. I’m not being complacent, I just don’t think the lessons of the 1930s have been forgotten. But if anybody is not familiar with them, I think they ought to read George Orwell. People who forget their past are doomed to relive it. That’s why we’ve got to make sure we don’t forget that past.”

It is beginning, I suggest, to look horribly reminiscent.

“Yeah. But we’re not there, and we can ensure we never are there. But an old man’s optimism is by definition short-term. And I’m an old man.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion