If your abiding image of Naveen Andrews is as Sayid from Lost – the soulful Iraqi officer whose sad eyes, powerful biceps and luxuriant hair set many mid-00s hearts a-flutter – you might be in for a shock seeing him in The Dropout. Paunchy, bespectacled, greying, with shockingly normal-length hair, he is less a strapping man of action and more a middle-aged man of business – and not a very good one at that. Andrews portrays Sunny Balwani, the partner and alleged co-conspirator of Elizabeth Holmes, who was once the world’s youngest female billionaire and is now a convicted corporate fraudster.

On a video call from his home in Santa Monica, California, Andrews, 53, looks more Sayid than Sunny. His black gym vest exposes reassuringly well-toned biceps; the hair is returning to its trademark resplendence. He gained 9kg (1st 6lb) for The Dropout, he explains, to make his face fuller and his belly paunchier. He also modified his movements to seem slower and older. “Well, I did at least want to resemble the character I was playing,” he says, a little sting of sarcasm in his inflection.

Andrews has lived in the US for 22 years, but there is nothing American, or even mid-Atlantic, about him. He speaks with a middle-class London accent that he has seldom had the chance to deploy on screen. In person, he is playfully arch, refreshingly honest and liberally sweary. You could easily imagine him holding forth in a pub in Soho, as he often did during what he freely admits was a youth misspent on drugs and alcohol.

He has few regrets about leaving Britain. “I miss old buildings – the sense of history, maybe; some aspects of the English countryside; Richmond Park; Hampton Court Palace. But I don’t miss anything else about it,” he says. It wasn’t just disillusionment with his home country. “There’s a certain kind of lifestyle that I didn’t feel I could escape by living there, rightly or wrongly. I don’t know what would have happened if I’d stayed. A lot of the people I knew from that time are not alive any more.”

Andrews still follows British politics, however. “I can’t help it; it’s like looking at an accident from afar,” he says. “I find it ironic that the country is being undone by its ruling classes.” When we discuss how willing people were to believe the hype around Holmes and Balwani, he turns the conversation to Boris Johnson. “You just have to look at parliament. You see [him] at prime minister’s questions refusing to answer any questions, lying through his teeth every time he opens his fucking mouth, and everyone goes along with it. So why shouldn’t that happen at a corporate level?”

The Dropout is very much a parable for our post-truth, late-capitalist times. For the uninitiated, Holmes dropped out of Stanford in 2004 after founding Theranos, a next-generation health company that claimed its machines could analyse one drop of a patient’s blood and make a diagnosis in seconds, thus bypassing the testing industry and the painful ritual of needles in arms. Holmes was compared to Steve Jobs. Powerful politicians and CEOs joined Theranos’s board. Major corporations invested billions. Except Theranos’s technology never worked – a fact that was successfully concealed for more than a decade.

Holmes met Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, a wealthy Pakistani-American software developer, when she was 18 and he was 37. Balwani invested in Theranos and became its chief operating officer. He was also secretly Holmes’ romantic partner for 12 years, it later emerged. According to The Dropout, Balwani moulded Holmes (played by Amanda Seyfried) into CEO material (black sweaters, green juice drinks) and established the corporation’s bullying, deceitful culture. These craven characters would not be out of place in a Shakespeare saga, Andrews suggests, although, as love stories go, it is probably more Macbeth than Romeo and Juliet. “He was besotted with her,” says Andrews of Balwani. “And probably still is, in some way. There was a romantic aspect to it which colours everything. How far are you prepared to go? When you love somebody that deeply, what will you do?”

Balwani is still awaiting trial; Holmes’s trial was in court as The Dropout was shooting. “It was like a play within a play,” says Andrews. “We would be on set doing the scene and then we’d have breaks and be looking to see what had happened in the trial.” The scripts were being revised as new information emerged, including some excruciating text messages. (Balwani: “Missing u in every breath and in every cell.” Holmes: “Ditto.”) “It worked to our advantage in a very strange way, because, very early on, Amanda and I made a decision about what kind of relationship it was; the level of intimacy. When you do these kinds of things, it’s a gamble; you don’t know if it’s on the money or not. And then all these texts came into the public domain which made us feel that we may be close, thank goodness.”

Beneath the physical transformation, Balwani’s identity as a south Asian man in the US was all too familiar to Andrews. “The idea of displacement, or the idea of a fundamental, deep insecurity that perhaps he’s not even aware of – I felt that was behind nearly everything,” he says. “I was able to relate to this emotionally: if you grew up in a place where you’re not welcome, and you deal with that on a day-to-day basis, it does something to you.”

Andrews’ parents emigrated from Kerala to Wandsworth in south London in the mid-60s. Racism was an everyday childhood experience. “One of my earliest memories is my mum pushing me in a pushchair along our road and the nextdoor neighbour’s girl – later on, she fancied me – who was maybe 10 or 11, running alongside going: ‘Golliwog! Wog!’” he says. “My mum says I was waving back at her, because I didn’t know what she was saying. And then, obviously, later on, it’s more violent.” He goes no further. “I don’t mean to sound like a victim, because I know people who’ve really been through it, you know? I’m still here.”

His parents scraped together enough money to send him to private school, which set him on a path towards drama, but also a path away from his conservative-minded family and towards alcohol and, later, heroin. He left home at 16 and moved in with his married maths teacher, who was 15 years his senior. They began an affair and later had a son, by which time Andrews was at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Such a relationship would have been illegal under “abuse of position of trust” legislation passed in the 00s, but it was not then against the law.

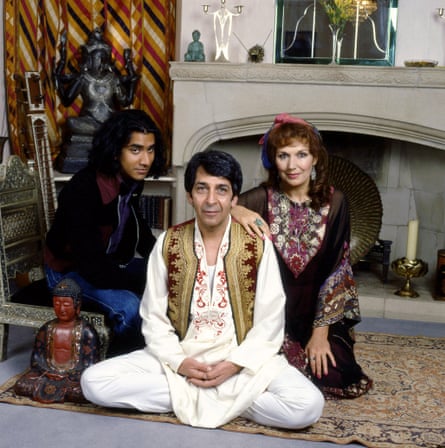

Andrews’ early career coincided with a new wave of British-Asian storytelling in the early 90s. He had parts in London Kills Me, written and directed by Hanif Kureishi, and in the comedy Wild West, about a British-Pakistani country and western band. Then, at 23, he was the lead in the BBC’s The Buddha of Suburbia, adapted from Kureishi’s semi-autobiographical novel (the author also grew up in south London, a decade earlier than Andrews) and boosted by a David Bowie soundtrack.

That led to Andrews’ breakthrough role in Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient. He played Kip, a bomb-disposal expert whom Juliette Binoche catches bathing. His acting career was on the up, as was his reputation as a sex symbol. Those must have been good times, I suggest. “Oh, I was too out of it to even register, to be honest,” he replies. “Because when you’re in that kind of condition, I can say now, you’re not really aware of what’s happening at all. You’re not present. It’s very odd.”

He was just about keeping it together enough to function, replacing heroin with alcohol while he was on a job. Then, in 1997, he collapsed on set and required medical treatment. He checked into rehab and has been clean ever since. “I don’t want to dwell on it, but it’s a daily struggle,” he says. “But one that I want to keep struggling along.”

Andrews moved to the US after shooting the 1999 road-trip romance Drowning on Dry Land, in which he played an Indian taxi driver driving Barbara Hershey from Manhattan to the Arizona desert. The on-screen love affair continued into real life – Andrews and Hershey were together for 10 years – although during a brief separation he had a son with a different woman in 2005. It is not difficult to imagine what tempted Andrews away from London. “I was like: ‘Where the fuck have I been all my life?’” he says. “Because I was [in California] and, you know, the weather! And at least on the surface, the apparent openness of America compared with England was quite attractive. And also I was trying to stop drinking and I was very lucky to meet someone here that I admired a great deal and helped me get sober.”

Then, in 2004, came Lost. It is easy to forget just what a big deal the show was in the early 00s. The combination of post-9/11 disaster scenario, the maddeningly mystifying plot and the hot young cast made it a must-see show – and the perfect material for the relatively new forum of online discussion.

Andrews played one of the show’s most intriguing and beloved characters, although he had no more idea of what was going on than most viewers, he confesses: “We really knew bugger-all. I mean, I don’t know if it would have helped. It was a strange feeling not knowing what direction this thing was going in, and yet you were committed to it.” Did he ever ask the showrunners what was going on? “There was no point in ever being that direct, ’cause you weren’t going to get a straight answer, were you?”

If he had to, could he explain Sayid’s arc through six seasons? “No. I don’t know if there was any kind of logic to it at all,” he says. “I could be completely wrong. There are people who love it and see something in it, and I’m glad if they can. But I can’t.”

Andrews was attracted to the idea of portraying a broadly sympathetic Iraqi character at the height of the war on terror. Sayid stands in stark contrast to Islamophobic stereotypes being trotted out in so many American shows and movies of the time. His decision to take the role was also influenced by his experiences as a brown-skinned man travelling regularly through US airports. Countless times he was taken to a side room and searched by customs officials. “It’s even happened where I’ve been recognised by the people who’ve taken me out of the line,” he says with a laugh. “They’re going: ‘We know who you are. We’re really sorry, but we have to do this.’”

Sayid was even allowed some romantic agency. His relationship with Shannon, played by Maggie Grace, was Andrews’ idea. In an interview at the time, he said: “I thought: what would really shock middle America? What if Sayid was to have a relationship with a woman that looked like Miss America?”

On the other hand, Sayid was also Lost’s resident torturer, thanks to his Special Republican Guard training. There are numerous, protracted episodes in which he extracts information from his fellow castaways using brutal methods, while reciting lines such as: “Perhaps losing an eye will loosen your tongue.” Meanwhile, in the real world, it was the US military that was torturing Iraqis, as the Abu Ghraib prison scandal revealed. Wasn’t there something a bit hypocritical about that?

“You’re absolutely right,” he says. “But you also can’t deny that in Syria, Iraq, Egypt – India, too – torture is something that’s applied on a daily basis, even in the smallest police stations, for absolutely nothing. It’s part of our culture.” He sees me grimacing to hear him say this. “I hate to say that, but it’s true, man! And you can’t deny it.” To gloss over these aspects of his and other cultures is no better than one-sided negative stereotyping, he argues. Had Sayid simply been a torturer, he would never have accepted the role, but that wasn’t the case: “He was presented as somebody with a soul.”

You could say Andrews provided him with that soul, as he has done with countless other characters, even Balwani. Andrews is good at his job, yet seems to have a healthy perspective on it. He is not desperately seeking the next role. When promotion for The Dropout is over, he says, “I’ll just go back to my regular job, which is being a dad”. He fought for and won sole custody of his younger son when the boy was three. He is now 16, the age at which Andrews started to go off the rails. “He’s not into that at all. He lives next to the beach. He surfs, he fishes. It’s the lifestyle,” he says.

“Life is very weird. It’s so unpredictable and it throws up these things that end up working for you in a way you never thought possible. I always thought I only gave a shit about myself, and then to be forced to care about this child, being responsible, learning to cook … It has definitely given me self-esteem that I never had.”

I mention a clip I found online of a 23-year-old Andrews doing an interview for The Buddha of Suburbia, sandwiched on a park bench between Kureishi and Bowie. He remembers this one, he says. “The interviewer asked [Bowie]: ‘So, how did you feel about doing this?’ And, of course, he’s Bowie. He’s incredibly charming, erudite and he answered the question beautifully. And then it went to Hanif and he said his bit. And Bowie is saying: ‘I’d love to work with these two again.’ And I was thinking: ‘Yeah, right. You’re going to get into the limo and I’m getting the bus home.’

“And then it came to me and they said: ‘So, how do you feel?’ And I kind of looked up at the sky and said: ‘It’s just a job.’ Bowie stopped the interview: ‘Cut! Cut! Cut!’ He grabbed me and took me off and told me: ‘You can’t talk to the press like that.’ So, we came and sat back down and I gave the right answer. But, looking back, I have to say – and if he was here now I’d say it to him – you know what? I was right. It is a job.”

The first three episodes of The Dropout are on Disney+ now. The remaining four will be released weekly on Thursday