MOOSE JAW, SASKATCHEWAN — A Prairie Town in the Second World War

If there ever was a heartland of Canada, a place where our traditional pre-electronic age Canadian values of humility, hard work, family, honesty and cheerfulness are alive and well, despite modern consumerism, it is the broad, seemingly endless, wheat fields, dusty roads, massive skies, and small towns of Southern Saskatchewan. It is here that you can find young men from the big cities returning home to help with the family haying, where hockey and football still reign supreme over soccer, where heavy snows, parched winds or fearsome summer storms don’t make the headlines or induce environmental panic. This is Canada’s centre of gravity, a vast open land of farms and farm towns whose harvest is not only wheat, but some of the finest and most principled people on the planet. In Saskatchewan, common sense is always in style.

During the Second World War, the Canadian province of Saskatchewan stood at the heart of the enormous flying training endeavour known in this country as the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. While every Canadian province was involved, it was the three Canadian Prairie Provinces that shouldered the heavy weight—Alberta to the west and Manitoba to the east, along with Saskatchewan, creating an air training arena the size of Europe, but with the population of Ireland.

Moose Jaw, along with other cities like Medicine Hat, Flin Flon, Porcupine and Yellowknife, was one of those Canadian place names that immediately brought sniggers from Americans and Brits alike, synonymous with the back of beyond, the middle of nowhere, the uncultured wilderness. Moose Jaw was in fact a bustling prairie town. Canadian Pacific and Canadian National Railways both had stations in the city and the town was and still is an economic centre of the breadbasket of Canada. While the distasteful obscenities of total war never came within thousands of miles of prairie towns like Moose Jaw, Estevan, High River and Dauphin, they would feel the impact of the conflict in many different ways.

Many towns across Canada, but especially in the Prairies, had been devastated by dry weather, crop failures, the Great Depression and social stresses from the end of the 1920s through the 1930s. When the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan was signed into existence in 1939, town councils and administrators from Nova Scotia to Vancouver Island vied for the economic action and stimulus a training air base would bring to their faltering communities. The towns in the Canadian Prairies and the farmlands of Southern Ontario had the best shot at attracting the RCAF’s money and investment as they provided excellent weather (most of the year) and suitable made-for-flying topography uninhibited by mountains and rocky land, the best possible sites for pilot and air crew training.

The impact of the war on Moose Jaw and Moose Javians was not one of death and destruction, though there were deaths and injuries associated with the training at the base, but rather demographic change and economic growth. An influx of hundreds of new mechanics, administrators, instructors and the thousands of men they would service gave the restaurants, bars, cafés, hotels, taxis and clothing stores a much needed boost. As well, there were new jobs created for men and women with the construction and operation of the base itself—cooks, servers, carpenters, truck drivers, snowplow drivers and even flight instructors. The economy of every BCATP community roared into overdrive, but the economy and the social structure of Moose Jaw changed not just for the duration of the war, but for good.

Today, Moose Jaw is one of the key bases of the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the bulk of RCAF fixed wing pilots and its top brass commanders today can find Moose Javian DNA in their makeup. Home of Canadian Forces Snowbirds Demonstration Team, training of Canada’s next generation fixed wing pilots still goes on there at full bore on the Raytheon Harvard II trainer.

One Man’s Moose Javian Adventure

Harry Bernard Blakey was born on 13 August 1918, the oldest of four children born to Harry and Alice Blakey in the English industrial town of Preston, in the west English county of Lancashire. Harry senior, a marine engineer, instilled in his first born a sense of curiosity, a longing for adventure and a keen interest in the newly developed science of radio electronics. He also inspired young Harry to take up one of his hobbies and passions—photography.

Young Harry Blakey (with arms crossed) poses with work mates from Pius A. Baines & Sons, Preston, building contractors and cabinet manufacturers in his home town of Preston, Lancashire, England. Harry was apprenticing as a woodworking machinist. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

Recently, Harry’s life, photographs and love of this new land called Saskatchewan came to my attention through his nephew, Robert “Bob” Blakey, who wrote to me inquiring if these photos would be of interest to Vintage Wings of Canada. While we do not really have the ability to curate and properly take care of the actual negatives and prints themselves, I told Bob that I would love to see them. As they began coming though the email one at a time, I realized that they were solid gold. They gave a personal view of how just one man’s life came to be changed by the BCATP, Saskatchewan and Moose Jaw. His photographs were not necessarily of the aircraft, hangars and operation of the airfield, but rather his beautifully ordinary life and how he was able to perceive and capture in images the exquisite beauty of a town unlike his birthplace. Instead of being homesick, he invited his wife and kids to join him and even his brother after the war.

Harry Blakey and his beloved Kodak Vigilant. One of Harry Blakey’s pastimes was photography—a passion he inherited from his father. All his life, he would have a dark room in his home and would even process colour film. But throughout his war experience, Blakey carried with him a Kodak Vigilant Six-20 camera—with leather bellows that allowed it to fold for travel. The camera was manufactured from 1939 to 1949 by Eastman Kodak and was state of the art for personal advanced photography. This shot was likely taken at home as the mail slot and flowers in the windows would not be at an RAF training facility. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

Related Stories

Click on image

In these pictures, we see a handsome man with the serious yet dreamy look of a man who sees what is around him and is affected by it. I never knew Harry Blakey, but he looks like a man who would have been quiet and determined, happy with his lot in life. These photographs tell the story of just one man, one of a hundred thousand whose stories have all but vanished. He was not an ace. He did not take the fight to Berlin with Bomber Command. He was not mentioned in despatches. But Harold Bernard Blakey was the very backbone of England’s war effort, the quiet man with an open heart who did his duty. The power of Harry Blakey’s life lies within these photos. In general they tell the story of every man who did his duty, but in particular, they tell the story of the many who came from Great Britain and, in Canada, saw the opportunity, the open minds and open skies of the greatest nation on earth. Harry Blakey, like Archie Pennie, Bunny McLarty and Harry Hannah, felt welcome and saw their futures played out upon the Canadian landscape.

When 21-year-old Harry Blakey joined the Royal Air Force at the beginning of the Second World War, he was inducted, trained and sent to learn his radio technician trade at No. 10 Service Flying Training School at the Royal Air Force airfield at Ternhill in Shropshire, England. He had no notion of Canada or Saskatchewan, a word he likely could not pronounce in the summer of 1940. In the fall of 1940, orders came to pack up No. 10—its equipment, tools, administration and airmen—and move the whole kit and caboodle by ship, through the U-boat infested waters of the Atlantic to Canada... to, what was it?... Sa-ska-cha-wan? And good Lord... some godforsaken wheat town called Moose Jaw! Can you believe it?

Aircraftman Second Class Harry Blakey (foreground) practices at a rifle range at RAF Ternhill with a Pattern 1914 Enfield .303 rifle, the service rifle of the British Army in the First World War. Ternhill was, and is today, a small Royal Air Force base in Shropshire in west central England. Ternhill was host to several flying units in the First and Second World War but, from 1939, it also was the home of No. 15 Personnel Transit Centre (PTC) as well as No. 10 Service Flying Training School (SFTS). According to Harry’s identity card (below), he was issued the identity document on 14 June 1940 at Ternhill. As he did not leave the base for another 6 months, it was unlikely that he was at the PTC as he would have only stayed for a couple of weeks at the most. Looking into the history of No. 32 SFTS in Moose Jaw, where Harry ended up, I learned that No. 32 was originally numbered No. 10 SFTS at Ternhill in Shropshire, England, and that this school was moved as a unit to Moose Jaw in November 1940 and renumbered as No. 32. So Harry was essentially with the same school in England as he was in Saskatchewan. Image: Harry Blakey collection via Bob Blakey

The interior of Harry’s Royal Air Force identity card, showing his arrival at Ternhill, 14 June 1940. His photo appears to be clipped from a group shot. Image: Harry Blakey collection via Bob Blakey

On 17 December 1940, Aircraftman Harry Blakey set sail on the troop ship SS Leopoldville, headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia along with other members of No. 10 Service Flying Training School from RAF Ternhill, bound for Moose Jaw. Here Harry gets one of his mates to snap a photograph of him somewhere in the North Atlantic, at the stern of his troopship. Image: Harry Blakey collection via Bob Blakey

Like many an RAF airman destined for Canada or coming back to the United Kingdom, Harry’s ship on the trip to Halifax was the old liner SS Leopoldville. Here, I have marked out exactly where Harry was standing when the previous photograph was taken. SS Leopoldville was an 11,700 ton passenger liner of the Compagnie Belge Maritime du Congo. She was converted for use as a troopship (TSS—for Troop Steam Ship) in the Second World War, and while sailing between Southampton and Cherbourg, was torpedoed and sunk by the U-486. As a result, approximately 763 soldiers died, together with 56 of her crew. Photo via u-boat.net

A Halifax harbour pilot boat meets Harry Blakey’s Belgian-registered troopship outside the approaches. Harry walked down the gangway onto the wharf at Halifax on 29 December 1940, boarded a train immediately and was stepping off the railcar in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan in the dead of winter just three days later, having journeyed nearly 4,000 kilometres in that short time. I have heard that many arriving British, Australian or New Zealand airmen were not overly impressed by the sooty and rough and tumble city of Halifax upon arrival. Halifax, the single most important port on the west shore of the Atlantic Ocean in 1940, could be forgiven for its untidiness, not because there was a war on and it was crowded with transiting soldiers, sailors and airmen, but largely because the entire central part of the city and Dartmouth, its sister city across the harbour, was wiped off the face of the earth just 24 years before in the Halifax Explosion, a 2.9 kiloton detonation caused when a French munitions ship by the name of SS Mont-Blanc exploded in the harbour following a collision with another ship. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

When they got there, at this brand spanking new base on the Canadian prairie, the average temperature was well below zero Fahrenheit. The school set up shop after being renamed No. 32 Service Flying Training School and took receipt of their brand new North American NA-66 Harvard IIs. Shortly after that, young Leading Aircraftmen from England began arriving by train in Moose Jaw, after crossing the Atlantic gauntlet—ready to begin their advanced service flying training. Of these sons of Great Britain, most would earn their wings, a few would die trying, many would perish on operations, some would endure prison, all would endure deprivation of some sort, many would survive and some, like Harry Blakey, would love their time in Moose Jaw so much that they would return to become citizens of Canada.

After Harry’s time with No. 10 and No. 32 SFTS, he finally made it to the fight, in one of the most exotic theatres of operation—Burma. There is not much here on that time, but then, this is about Harry’s time in Canada and why he returned. I will let Bob Blakey finish Harry’s story

“After the war, Harry returned to civilian life in England and opened up a radio repair shop in Preston. However, he soon became disillusioned with postwar Britain. He missed the friends he had made in Saskatchewan and saw more job opportunities there. In 1947, he and Jenny and the girls became immigrants to Canada, and never left. He and Jenny had two more children – both boys – Charles and Raymond.

Harry was always close to his next-youngest brother Robert (my father, a British Army veteran), so he persuaded our family to leave England and immigrate to Canada, which we did in the early 1950s. I was five when I arrived in 1952, and like my cousins, have remained a Canadian. With encouragement from my uncle and my father, I spent four years in the Royal Canadian Air Cadets, as did my cousin Charles (Chuck). We became very familiar with that RCAF base that Harry first saw in 1941.

As a career, Harry repaired radios (and, later, TV sets) for Eaton’s in Moose Jaw. Except for a couple of years in Lethbridge, working for Canadian Pacific Air, he stayed in Moose Jaw. His final work before retiring was teaching electronics at the Saskatchewan Technical Institute in the city.

Photography was such a strong interest for Harry, he shot thousands of photos. His children and relatives are grateful that he also preserved the negatives. He always had a black-and-white darkroom in his basement and in his final years did his own colour-film processing and printing as well. For several years after retirement, he did freelance photography work, including weddings.

Throughout his adult life, Harry was active in veterans’ groups, especially the Army, Navy and Air Force (ANAF) Veterans Association. He got involved in lobbying the federal government for better benefits for vets. His whole life he socialized with Second World War veterans and always retained ties with the RCAF base nearby.

In February 1979, Harry died of a heart attack. He was 60. An honour guard consisting of ANAF vets and Legion members attended the funeral and organized the reception.”

Without men like Harry, much of the simple things, the things we take for granted, from those days would slide easily behind the forgotten veils of history.

Harry Blakey, Prestonian turned Moose Javian, Englander turned Canadian, the airman turned citizen, this is for you... your photos for the wide world to finally see.

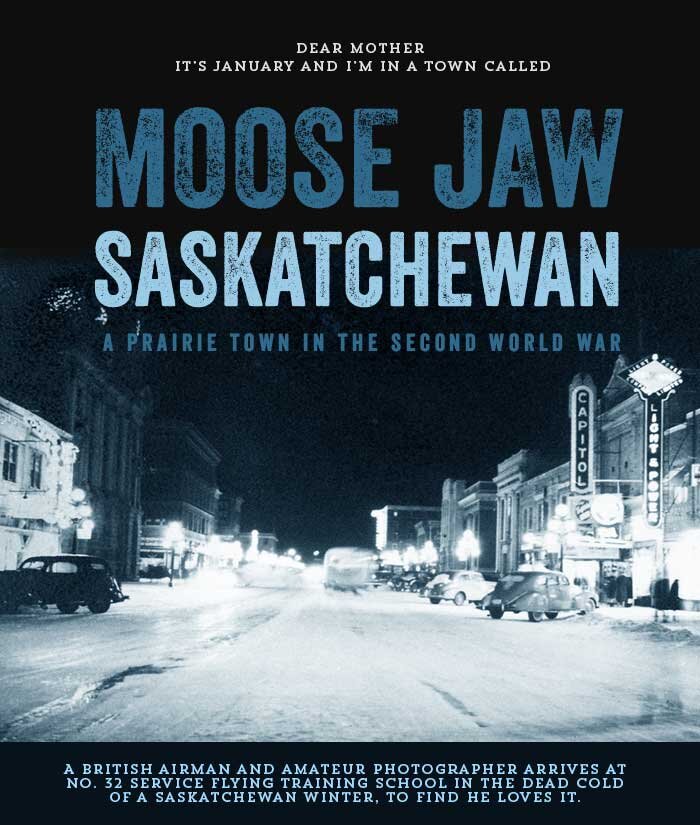

The winter of 1940–41 in Moose Jaw was as mean and hard as any on the locals, but one can imagine what a shock it had to be for men from the Cotswolds or the warmth of Gladstone, Queensland. It seemed that Harry Blakey embraced the weather and the people immediately, photographing around the prairie town of Moose Jaw, which lay eight kilometres to the north of No. 32 Service Flying Training School where he trained and eventually worked. There is one thing colder than a winter’s day in Moose Jaw, and that is a winter’s night. Here, while the café, theatre and tavern lights of downtown weekend Moose Jaw signal warmth and welcome inside, Harry stands in the middle of Main Street, not long after his arrival and sets up a time exposure. A bus blurs off into the distance, while cars and shoppers line the street. The magic lies in the bright welcome offered by the prairie town which contrasted so drastically with the blacked-out cities of Blakey’s England. In the lower right, we see a shadow and a blurred shadow of a man, maybe two— is that you Harry? Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

It is doubtful that Moose Jaw’s Wimpy’s Hamburger Shop of the 1930s and 1940s was inspired by the chain of Wimpy Burger restaurants in England, as that enterprise had barely gotten off the ground by the beginning of the war and had only 12 restaurants in England by the 1950s. Instead, it is simply likely that this establishment, now long gone from Moose Jaw, was simultaneously named after the same fat, hamburger eating character from the animated Popeye cartoon by the name of J. Wellington Wimpy—pictured here on their sign on River Street, Moose Jaw despite the obvious copyright infringements. On the other hand, Amil’s Taxi has been in continuous operation since 1924 and is still the number one taxi company in the city today. Note the four digit telephone number. Moose Javian Todd Lemieux remembers Amil’s fondly from the not too distant 1980s: “You bet Amil’s Taxi has been around for a long time... we used to take two of them, drive down Main Street, open the windows and crawl from cab to cab with the drivers still driving.” Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

While many of his mates were hunkered down inside on the base or in Moose Jaw’s fine social establishments, Leading Aircraftman Harry Blakey of Preston, England shouldered his tripod and camera and roamed the streets, driven by a passion to record and express the simple beauty of the place he loved and would someday call home. Here he stops on Langdon Crescent to capture a winter scene. The photograph is looking south towards St. John’s Anglican Church (today known as St. Aiden’s) in the thin winter light. We asked Todd Lemieux, Vintage Wings Chairman and warbird operator, about this scene: “It’s the church my family attended and still attends, I was baptized there, confirmed there and was a choir boy there (no joke). It contains two original crosses that survived the battle of Vimy ridge”. The park on the left of this photo, called Crescent Park, was built during the depression-era 1930s by men on relief. To the extreme right, off camera, is the famous dance hall known as Temple Gardens. Temple Gardens was THE dance hall in Southern Saskatchewan and one of the centres of social life in Moose Jaw. It had hardwood floors laid over a bed of horse hair and all the big travelling acts played there during the war years and after. Art Linkletter, who was born and orphaned in Moose Jaw, was a host there in the early years, and beloved CBC radio host Peter Gzowski also announced there for Moose Jaw radio station CHAB when he was editor of the Moose Jaw Times Herald. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Not sure why I am always compelled to look to see what the same place would look like today, but thanks to Google Maps, I can visit the same spot as in the previous photograph more than seventy years later and see how things have changed. This view is also looking south on Langdon Crescent with Crescent Park to the east. Image via Google Maps

A Temple Gardens advertisement found in a 1942 copy of “Prairie Flyer”, the newsletter/periodical of life at No. 32 SFTS Moose Jaw. Cover charge was anything from 20 to 50 cents depending on the expected crowd. Clearly, Saturday night’s Week End Hop, with flying training shut down, was the big night for airmen stationed at the base. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada

In a shot that today would be called classic editorial, suitable for a high end magazines like New Yorker or Harpers, Blakey captures the image of three airmen in the kitchen of one of the messes at No. 32 Service Flying Training School. In many of Blakey’s photos, the Moose Jaw air base still looks shiny and new, which of course it was. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Blakey was particularly interested in the photography of architecture and took photographs of churches, civic buildings and edifices. His eye for balance and symmetry was expressed in this wartime image of Moose Jaw’s Central Collegiate Institute (CCI) in wintertime. This is the same high school which graduated our Chairman of the Board Todd Lemieux and his father before him. CCI has stood on Oxford Street West since 1909. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Harry spent some of his spare time photographing the flight line of No. 32 Service Flying Training School. Here during the winter of 1940–41, the pilot of North American Harvard 2735 trundles away from the line, with two others in the background. We know it to be the first winter after Harry’s arrival as this Harvard was taken on strength with the RCAF as Harry was crossing the Atlantic, but suffered Category A damage on 28 August 1941. It was written off and reduced to spares by December 1941. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Judging by the lack of oil and hydraulic fluid stains, shiny tire rubber and highly polished propeller speed governor, the Harvard that airman Harry Blakey is touching is brand new. One of a large batch that was sent to No. 32 at the beginning of its years at Moose Jaw and Harry was there at the outset. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

After the first winter, Harry experienced the beauty and seemingly endless days of a Prairie summer. Here, standing on the ramp of the hangar line and looking to the east, Harry captures a busy flying training school under perfect flying conditions. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

On his off-hours and on leave, Harry enjoyed visiting friends in nearby Mazenod, Saskatchewan, south of Old Wive’s Lake. Here, he could hang out and hunt with a Canadian named Frank Hamilton, an airman of the RCAF, whose family welcomed him like another son. Here we see Harry holding a pheasant he has just shot with a rifle out on the prairie grass. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

Harry (left) poses with members of Frank Hamilton’s family in the shade at their farmhouse near the tiny hamlet of Mazenod, Saskatchewan. His friend Frank stands beside him and next to his brother Geoff. We can see the white forehead of Mr. Hamilton’s classic farmer tan... evidence of the hard work of farming on the Canadian prairie. Frank Fletcher Hamilton (inset) served with the RCAF from 1940 to 1951. He completed two tours with Bomber Command and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and Distinguished Flying Medal. He returned to Canada in 1944, married his wife Olga and remained on strength with the RCAF flying transports in the Arctic and instructing the first NATO pilots. He became a Progressive Conservative Member of Canadian Parliament through four successful elections from 1972 to 1984. He died in 2008. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

Probably not one of Harry’s photos, but in his album of Second World War mementos, this photo shows a group of electrical technicians and mechanics in coveralls posing brightly for a base photographer in front of workshop doors. Harry stands at left in the back row with his coffee mug in hand. Judging by the 100% use of coveralls and even a fur hat, this was likely sometime in the spring of ’41, ’42 or ’43. Harry came to No. 32 SFTS to apprentice as an electrical/radio technician, and stayed for more than two years, before leaving for Southeast Asia in 1943. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

A wonderful and formal group shot taken in front of one of the Harvard aircraft of No. 32 Service Flying Training School. Harry stands at far right in back row. As Harry is always on the end of a back row in the three group shots above, I have to wonder if he had not set a timer on his own camera and run into the shot. I was not able to determine if there was any specific numbered school of electrical and radio repair at Moose Jaw which Harry might have attended during his stay in the Prairies. It is more likely that he apprenticed at the Flying School or because of his previous pre-war experience he may have been able to skip formalized training. After a seven year apprenticeship as a woodworking machinist in Preston, Lancashire and before enlisting, Harry had turned his attentions to something that truly captured his imagination—radio-electronics. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

Harry Blakey, left, and two of his Royal Air Force chums at Moose Jaw. The airman in the middle is Win Baron, one of Harry's best friends during the Second World War. Win Baron. Win married a girl form the Moose Jaw area and returned to England. He owned a furniture business and moving company. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

Today, this portrait would be called a “selfie”, as Blakey sets up his timer to capture this dark and moody shot. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

After his first tough winter in Moose Jaw, Harry Blakey was rewarded with a visit of several months from his wife Jenny and their two daughters. Like Harry, Jenny ran the U-boat gauntlet in a troopship escorted by destroyers. Here, in a photo taken in the summer of 1941, Harry and Jenny pose in Moose Jaw with their daughter June and a farm dog. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

A breathtakingly beautiful colour photograph of Jenny Blakey, taken in the Rockies by Harry on a trip the two took while Jenny was visiting Moose Jaw in 1941. Everything about this photograph is remarkable to me. Though there is no aircraft, airfield or airman in the photo, it is a vital part of aviation history. In 1941, with the visit from Preston of his family, Aircraftman Harry Blakey was granted leave, and with his wife (and possibly his daughters) drove west to the Rocky Mountains. In the south of Alberta, Harry and Jenny crossed the American border into the Big Sky State of Montana headed for Glacier National Park. Harry could not cross the border in uniform as the United States was officially neutral at that time. He took this remarkable Kodacolor photo of the passenger tour boar DeSmet at the lodge dock on Lake McDonald at a time when that type of colour film was not yet available to the general public. An avid photographer, Harry had a friend at the Kodak plant in Rochester, New York, who had procured for him some of the still experimental film to try.

Harry shot a full roll on the Montana trip then mailed it to his friend for processing. Harry’s nephew Bob Blakey explains: “Although colour photography wasn’t new – Kodachrome slide film, for example, had been introduced in 1935 – a film that could produce colour negatives for easy print ordering by consumers was something of a holy grail in the industry, and Kodak led the way in North America. (Globally, I believe the Germans did it first.)

This is most likely the first colour-negative image ever shot of that tour boat and lake. Harry’s son Chuck Blakey and I found the negative about 10 years ago after much searching among his father’s neg files (in the 1970s, Harry told me the Rochester story, so we knew the negs were there somewhere) but I wasn’t able to fully restore this image’s colours until 2011 using modern software. Even so, the Kodacolor neg has actually held up well considering its age. Not so the original prints Harry got back from Rochester, which turned to shades of orangey brown by the early 1950s. Kodak had gotten the film technology right, but had a long way to go with colour paper.” Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Young Patricia Blakey puts a supportive arm around her sister June. When they came to Canada with Jenny, Blakey took the opportunity to photograph his two toddler daughters, an image which would comfort him in his journeys through a frozen new world and then on to a tropical Burma. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

In the winter of 1941–42, Harry Blakey visited Calgary and Banff, Alberta where he captured this perfect photograph of the Banff Springs Hotel, a favourite stop of airmen on leave in the Canadian prairies of the Second World War. Though airmen seemed to want to visit Banff and the beautiful chateau-style hotel, as 1941 closed, the hotel closed its doors for the duration of the war due to lack of business. With no flag on the flagpole, boarded up windows and walkways and drives not cleared of snow, it is likely that the photo was taken in the first months of 1942. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

On his trip to Banff in the Canadian Rockies, Harry also visited Calgary, where he took this image of 8th Avenue in downtown. At the left we can see the sign for the Victoria Hotel, a favourite drinking spot for the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry – PPCLI. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

A photo of Harry on another leave in the Rockies, possibly the same trip as the previous photo. Harry carries his Kodak Vigilant camera and his always present cigarette in this shot set up on a tripod and useing a self timer. Since the negative for this shot was in the collection of Harry Blakey, we can then assume it was from his camera, which means that he had two cameras by this time. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

Another “selfie” by Harry Blakey, with his cigarette in hand. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

In the spring of 1941, Harry set up on Athabasca Street to take a photograph of one of the city’s most beautiful buildings—the Gothic St. Andrews United Church, a Moose Jaw landmark since 1914. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Harry left Moose Jaw for the war in Burma in 1943, but in 1947 his love for the town and the open prairie sky brought him back to stay in Moose Jaw permanently. It was as a Moose Javian that Harry Blakey captured this dramatic photograph of St. Andrews on fire on a frigid December night in 1963. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Harry, ever the photographer looking for the dramatic image, was back at St. Andrews a couple of days later to capture the terrible but beautiful destruction. The Church was rebuilt to the same design two years later. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

In 1943, Harry returned to England briefly after his apprenticeship and work at No. 32 SFTS Moose Jaw. Here we see him, looking tall, dark and handsome in his Royal Air Force kit, standing with his daughter June. In the background the sombre and treeless streets of his hometown of Preston in Lancashire, Northwest England, a boom town of the Industrial Revolution. From here, Harry joined the war effort in the China–Burma–India Theatre of Operations. After returning to Preston from Burma after the war, Harry set up a small radio repair business. Soon he started to miss his friends from Western Canada and became disillusioned with post-war England and the social, housing, economic deprivation and de-industrialization problems of working class cities like Preston. He missed the clean air, trees and wide open spaces of Moose Jaw and the heartland of a country that had captured his heart. By 1947 he was back in Moose Jaw, with Jenny, June and Patricia. In Moose Jaw, the Blakey clan would increase by two sons—Charles and Raymond. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey.

Bob Blakey was only able to find a single image from Harry’s days in Burma and India—this shot of Corporal Harry Blakey in tropical khaki kit and the omnipresent cigarette. After sweltering Burma and India as well as his disenchantment with post war Preston, England, Harry longed for and eventually returned to the prairie life. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

Harry, with his ever present cigarette and a cold beer, poses with his wife Jenny (closest to the camera) and a friend drinking more sophisticated red wine at a bar in Moose Jaw, likely after the war. The fourth person at the booth (Frank Hamilton) has stood back to capture the image. Harry has returned from two years in Burma and two in Preston, while Frank has survived two tours in Bomber Command. The beer tray on the plate rail behind Harry extols the goodness of Palomino Fine Beer. Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

This photo was taken a few minutes and half a glass of beer after the previous photo at a bar in Moose Jaw. The friend with Harry is Frank Hamilton. Jenny sits with Frank’s wife Olga. Frank was lucky to survive two tours in Bomber Command, earning a DFC and a DFM. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

This photograph, judging by Frank Hamilton's clothing, was taken on the same evening as the previous one. The sign in the background states that persons under the age of 21 were subject to a $100 fine (huge in those days) and up to 30 days in jail. Since Frank was born in 1921 in April, we can calculate that this evening was not during Jenny Blakey's 1941 visit to Moose Jaw (Harry was born in August, 1918) . We can assume that this was likely post war after Harry's return to Moose Jaw. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

After the war, Harry tried to pick up his life in Preston, but became disillusioned with the economy and social pressures in England and in his industrial home of Preston. He moved his family back to Moose Jaw, where he had felt so welcomed, bought a 1940 De Soto car and a home and started life anew. Here, sometime between 1947 and 1950, is Harry standing on the dirt roadway outside his new home on 7th Avenue North East in Moose Jaw, with the railway line running close by. The car as the prerequisite cracked windshield of a prairie car driven on gravel roads. Chuck Blakey recalls: “That as the house at 1143 - 7th Avenue NE in Moose Jaw. It is gone now, with the area being part of a flood control zone. He used to park the car in winter nearby on a downhill slope so they had a better chance of getting it started in the cold winters.” Harry had an abiding interest in anything mechanical and loved tinkering with cars. Bob Blakey remembers… “We talked for many hours at a time on numerous subjects. He had a phenomenal memory. He could quote from books and articles he’d read 20 years earlier, and his practical knowledge, especially on technical and engineering subjects, was deep. I remember when I started to mess around repairing cars and I mentioned to him a friend had a car with a straight-eight engine. I asked my uncle why they had gone out of fashion in favour of V8s and he gave me this incredible, detailed explanation about how modern high-octane gasoline led to high-compression engines and the long straight-eight crankshafts couldn’t take the strain, plus something about cooling passages and other details. Later, Dad told me Harry, as a kid, used to dismantle and reassemble engines with ease, and pretty much any other gadget or machine that caught his attention.” Image: Harry Blakey Collection via Bob Blakey

It wasn't long before Harry had convinced his younger brother to come on out to Saskatchewan, where a man with initiative and skill could create a life for his family, far from the polluted industrial cities of England and crowded council housing. Bob Blakey, Robert's son recalls : “This was when my dad was staying with Harry and family in Moose Jaw, earning money to bring my mother and me over from England. Dad was working at the Robin Hood Flour mill at the time, and he wore that old suit on the job. No money for denim or overalls in those days!” Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Living with his brother Harry, Robert Blakey (right) worked hard to get the money to bring his family over for a new start in life. Bob Blakey remembers: “My dad had come over a year earlier, then worked in a succession of jobs, each paying a little better that the previous one. When he had enough money to bring us over, my mother and I crossed the Atlantic on a Canadian Pacific ship, then travelled by CPR train from St. John, N.B. to Moose Jaw. So this was the first time the two families were together in one place since 1947.

I'm the taller of the two kids. Charles (Chuck–Harry's son) is next to me. My dad, Robert Blakey, is behind me. My mother (Winnie) is behind Chuck. Harry's wife/Chuck's mother Jenny is at the back. The car is the 1938 Dodge Harry was driving at the time. It's a bit of Canadiana. Note the plastic sheets glued to the windows, designed to minimize fogging on cold days. Lots of cars had them then. (The heater/defrosters in those days were almost useless.)”

Judging by the look on their faces, and the fact that this was the first day they of their new lives in Saskatchewan, they had not yet adapted to the legendary cold of a Moose Javian winter. In fact.. this was the morning of their very first day in Moose Jaw in February, 1952. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

Despite being thousands of miles from his homeland, Robert was quick to adapt and see in the prairie town of Moose Jaw what he wanted for his family. Here, Robert (with ball in centre) poses with his soccer team–the Moose jaw Wanderers, about a year after his family had arrived. The group relied on Robert's brother Harry to take the photo, as Harry was making a name for himself as a photographer. Recent posts on the internet indicate that the Wanderers were still playing soccer as late as 2008. Photo by Harry Blakey via Bob Blakey

One of the few shots of Harry (right) and Robert together was shot by Robert Jr. (Bob Blakey) in 1969. By this time, Robert Blakey had moved his family to the Seattle area and the two families could only get together on occasional vacations, like this one in Moose Jaw in 1969. The two men look like no-nonsense scrappers in this shot and Bob Blakey recalls: “He and my father spent part of their youth in some rough neighbourhoods in Preston and they had to learn how to defend themselves, ready to come to each other’s rescue when there was trouble, though Harry, being almost five years older than Dad, usually did the rescuing. Such skills came in handy during the early postwar Moose Jaw years because the place had a Wild West aura about it, with fights breaking out in bars so often that nobody thought it was a big deal. Harry and my dad were half Irish (on their mother’s side), but Harry was the one who most physically resembled their uncle Johnny Horan, who was a successful pro boxer all over England and Scotland early in the 20th century.” Of his relationship with his uncle, Bob Blakey reminisces: “Harry was brilliant, and I think I felt, as a kid, that I’d be wasting his time trying to engage him in conversation. I wasn’t worthy. But when I got into my teens and beyond, our relationship changed. I enjoyed his company and he enjoyed mine.” ...“He loved electronics, and his was the first family in Moose Jaw to have a TV set, around 1954. This was before there even was a local TV station. I remember when our family went over to look at this new gadget and all we could see were some wavy images from a signal broadcast from Minot, North Dakota. Harry had managed to rig up a tall antenna to pull it in. (Soon afterwards, CKCK-TV Regina signed on.)” Photo by Bob Blakey

Harry’s grave marker with the inscription: “Wisdom had he with a love of earth’s nature.” Returning to Moose Jaw after the war was not easy, but it would have been a tougher life for Harry and his children if he had stayed in Preston, and he and Jenny understood that. His son Chuck would appreciate what he did: “I was always grateful that my parents came to Canada. It was not easy when he returned to Canada after the war. Returning servicemen got first priority for jobs. In that my Dad was with the RAF, he was not a Canadian serviceman! But his children had great opportunities. My brother attended Saskatchewan Technical Institute in the electronics field. My sister June became a registered nurse with a B.Sc. My older sister Pat worked for a time as a lab technician but then raised a family of three children. I got some great experience in the RCMP, went to business school at the University of Calgary, Scurfield Hall, and then got my Doctor Juris degree. I am sure that, with the times and our status in England, we would not have achieved these life goals.” Image via Saskatchewan Genealogical Society