FROM SCRIPT TO SCREEN: 'Monster's Ball'

DAVID S. COHEN is a freelance writer, photographer and documentary filmmaker. His articles on film and television have been seen in print outlets around the world, including US Weekly, Premiere and Variety special reports.

Click to tweet this article to your friends and followers!

Will Rokos heard the words more than once. “This is the best script that will never get made,” he remembers. For Rokos and Milo Addica, his writing partner on Monster’s Ball, they were about the worst words a writer could hear. For Addica and Rokos hadn’t written Monster’s Ball as a writing sample or a calling card, and they weren’t looking for a screenwriting career. They were actors who had set out to write themselves the roles of a lifetime and along the way put themselves through a writing process so torturous, that it all but consumed their friendship of many years.

The duo saw their dreams of starring in the movie fade as a parade of famous names attached themselves to the script, only to see those famous names drive the budget intolerably high. Addica and Rokos had persevered through notes and rewrites that had threatened to undermine the things they valued most in their own script.

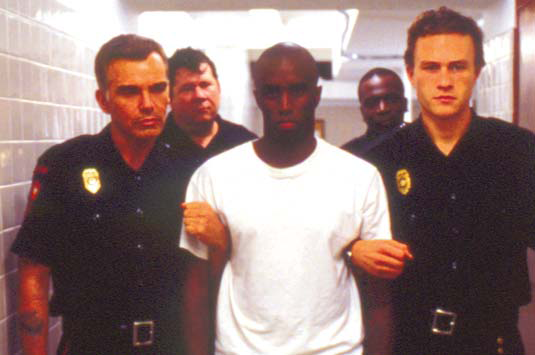

Heath Ledger (right) as Sonny Grotowski, Sean Combs (middle) as Lawrence Musgrove and Billy Bob Thornton (left) as Hank Grotowski in Monster’s Ball.

Yet somehow, three producers and a handful of departed stars later, Monster’s Ball found its way to the screen with a high-powered cast, a suitably low budget, and even a couple of supporting parts for Addica and Rokos themselves. While Addica and Rokos may not have received the same boost for their acting careers that Ben Affleck and Matt Damon got from Good Will Hunting, the story behind Monster’s Ball has much to teach actors who are thinking of trying their hand at writing or anyone who writes with a partner.

Monster’s Ball is a drama about three generations of executioners in a small southern prison town. (Those who have not seen the film should skip the following synopsis.) The protagonist is middle-aged Hank Grotowski (Billy Bob Thornton), a man caught between his own good instincts and the bile of his father Buck’s (Peter Boyle) racism and misogyny. Buck is an aged bigot slowly dying of emphysema, who spends his days collecting clippings about executions and watching bad TV.

Sharing the house with Hank and Buck is the youngest of the Grotowski men, Sonny (Heath Ledger). Sonny is just learning his father’s trade as the prison prepares for the execution of a black prisoner, Lawrence Musgrove (Sean Combs), who gets a last visit from his young son Tyrell and long-suffering wife Leticia (Halle Berry). Hank and Sonny keep Musgrove company during his final hours while across town Leticia flies into a rage at her son—an obese, compulsive eater.

When Sonny falters during Musgrove’s execution, Hank beats and humiliates his son. Sonny responds by threatening Hank with a pistol—but instead turns the pistol upon himself. Soon after Sonny’s suicide, Hank quits his job at the prison. Meanwhile, Musgrove’s widow Leticia struggles at her waitress job, trying to avoid being evicted from her small home. One rainy night, Hank passes Leticia on the roadside. A car has hit her son, and no one will help her. Something makes Hank stop and take the pair to the hospital. The boy dies at the hospital, and Hank takes Leticia home.

Over the next few days, Hank and Leticia begin an intense affair fueled by a mutual need to drown the pain of the deaths of their sons. But they have yet to discover the hidden links in their pasts and the racist Buck still holds sway over Hank at home. As truths are revealed, Hank and Leticia must face choices that neither of them could have imagined just a few weeks before.

Addica and Rokos met some 15 years ago while performing together in a New York production of Fools in the West, a spoof of Sam Shepard plays. Rokos was a 21-year-old from rural Georgia, while Addica, 2-years older and the street-smart child of “hippies,” had grown up in lower Manhattan. Somehow the two hit it off.

Rokos had already begun to edge toward writing with a stage adaptation of The Ox Bow Incident, a story which had had a profound effect on him after seeing the film version as a child. Addica was impressed and passed the script along to Harvey Keitel.

Addica had met Keitel at the age of 15 when the actor had been a regular in a Broome Street restaurant where Addica’s mother was waiting tables. “I was always enamored of him as an actor,” remembers Addica. Rokos and Addica had hoped that Keitel would direct The Ox-Bow Incident and that they might act in it, but though Keitel liked the script he never signed on to direct.

Addica and Rokos often spoke together during the years after the their show ended; and when Addica would bump into Keitel, Keitel would often mention Rokos and his good writing. By 1995, Addica and Rokos were in their ‘30s. Both had just ended relationships, and their acting careers weren’t thriving. They decided to take matters into their own hands and write a screenplay.

Their plan was to write a script for three major characters. Hopefully, Harvey Keitel would star opposite Addica and Rokos, so the pair holed up in Addica’s tiny Santa Monica apartment and began writing.

CYCLE OF VIOLENCE

As they started, the pair zeroed in on an area both had in common: troubled father/son relationships. “We both came from very dysfunctional homes, both Will and myself,” remembers Addica. “We both had difficult fathers that we really didn’t like. But we didn’t want to write something that would be indulgent and spiteful and take out our aggression on our fathers. But we knew we wanted to write something about father and son relationships—about there being a cycle of violence.”

They drew on their lives, basing characters upon people they knew—especially characters from Rokos’s hometown in the south. They soon decided to make their lead character an executioner. “We came up with an idea of an interesting job solely on that,” says Addica. “We were also both interested in the Gary Gilmore story, just the idea of an execution.”

In those days, before Dead Man Walking and The Green Mile, they had never seen a contemporary film about executioners, their lives and work. Research took them to a 1920s issue of Colliers magazine and a book called Death Work: A Study of the Modern Execution Process (by Robert Johnson). They discovered that executioners traditionally pass their trade from father to son.

“Originally, Sonny, Buck, and Hank were just roommates who shared a house and worked together,” Addica says. “When we found out that it’s generational, we said, ‘oh this is perfect.’ Once we changed it to his [Buck’s] son and he [Hank] was getting his son [Sonny] onto the death team, the story really started to speak to us.”

Their research into executions and executioners also led them to the title of the script. Monster’s Ball was an old English term for the condemned man’s last meal. The doomed man was the “monster” and the night before his death his jailers would give him a party or “ball” as a sendoff.

They started without an outline or a treatment—just a rough sketch of a father and son getting ready for an execution.“It was so far different from what we have now,” says Addica. “We didn’t have an ending. We didn’t even have a middle. We had only a beginning. The characters took different shapes. Hank was a much happier character. He was pursuing Leticia, and she owned an art gallery in town.”

Since neither was an experienced screenwriter, they turned to their acting as their main writing tool, improvising scenes and dialogue. It proved to be a fateful choice. “The experience of writing it was more than difficult,” remembers Addica. “We had to dig into ourselves to get to some of the layers of the relationships that we were writing about, especially the son and the father. Will and I would improvise a lot of these scenes, to get down to the essence of what we were trying to say and do.

We were improvising things about fathers, love and ‘what do I have from you, Dad? What did I ever have from you? Why don’t you love me? Why didn’t you ever love me? You never loved me. You never cared about me.’ That touches on me and my own life and my own dad and Will’s as well. And it was hard. “During a lot of that,” continues Addica, “you dig up a lot of stuff inside of you and reveal a lot of stuff inside of you to your partner. Afterwards, when the smoke settles, the feelings haven’t gone away. They’re still there, especially with guys like us who are from dysfunctional families.”

This went on for almost eight months with the pair living in Addica’s 10x15 apartment and flaying each other daily. They wrote “hundreds of pages” of dialogue only to pare them back again and again. Eventually, they distilled the searing emotions of their improves down to subtext, leaving much of the most painful emotions unspoken.

It is an unusual choice for writers, especially first-time writers. Few have the confidence to leave so much of the storytelling to the gestures and expressions of a still-to-be-determined cast. But Rokos says that as actors, he and Addica shared an affinity for those silences, and they deliberately chose to leave the script terse, almost underwritten.

“I know myself as an actor, I like to not talk very much,” says Rokos. “I know some actors like dialogue, want to add a line, where I definitely prefer not to talk very much. I think that’s what drew us together as artists when we first worked together. We like the inner stuff and the small moments.”

Addica remembers that they sometimes thought that dialogue would destroy the essence of a scene. “Sometimes less is best, you know?” says Addica. “But we didn’t know if people would get that reading the script. We had no clue.”

DESPERATE SEX

They completed their draft by March of 1996 and began showing the script to people they knew in the business. “The irony was it never got to Harvey Keitel,” Rokos remembers. Rokos had been acting in a Swedish film and showed it to the film’s producer who liked it and passed it along to Michael Lieber, an executive producer on Joe Gould’s Secret. “Mike got us our first writing agent,” says Rokos, “and got the script around L.A. It took off pretty quickly. We were lucky that way.”

In fact, interest in the script was so great that there was never a chance for Addica and Rokos to play the lead roles they’d hoped for. The script attracted the attention of top talent including Robert DeNiro, Tommy Lee Jones, and Marlon Brando. Oliver Stone and Sean Penn talked about directing.

Suddenly the pair of actor/writers found themselves stuck in “development.” Atlas Entertainment, best known for Three Kings, took an option on the script and asked for some changes. The first draft had included a series of flashbacks in which the audience learned that Hank had seen his father rape a small black girl when Hank was about 10 years old.

That was to pay off in a later scene, after Leticia innocently brings a gift to Hank’s house only to be verbally abused by Buck. “In our original draft,” says Rokos, “Hank literally dragged his father out to the tombstones where his wife and his mother and his son are buried and asked ‘Why did you do that to that girl?’ and physically beat him up, Billy Bob Thornton as Hank Grotoski and Halle Berry as Leticia Musgrove in Monster’s Ball. then put him in the home after that. The abuse remains in the script, and afterwards Hank decides to put Buck in a nursing home, but originally there was an explosion in between.

The flashbacks and the resulting confrontation were not the only elements to be trimmed when producers began giving notes. Atlas Entertainment let the script go and the option was picked up by Fine Line Features. The producers wanted more dialogue. They wanted a happier ending, and they wanted Leticia’s son to live.

“We were told that it was too grim with the child dying, and nobody would want to see the movie if the child died,” says Rokos. “We were kind of surprised to get so much resistance on that, but the producers had the option on the script, so if they wanted the kid to live, the kid was going to live.” They penned a new ending with Hank nursing the boy back to health and teaching him to box, so his classmates wouldn’t be able to pick on him at school.

“Neither one of us was very happy about that,” says Rokos, “but we heard once that Hank would win an Oscar if the kid lived.”

Addica and Rokos knew that this undermined one of the cornerstones of the script: the pain of loss that brings Hank and Leticia together. “The whole point of the relationship between these two people is that they’re together because they both have lost sons,” explains Addica. With that in mind, the script’s sex scenes are so raw that they’re almost painful to watch.

“We didn’t want to write perfect, clean sex,” says Addica. “Nothing to do with lovemaking. They’re people who are f***ing because they’re desperate.”

By this time, Addica and Rokos were having their own differences. By their own descriptions they are both opinionated, strong-willed people, with their own ideas of how the script should go. Their partnership, always tenuous, soon ended.

Rokos, for his part, says little about the breakup: “We never set out to be a writing team. That’s all. We did one more script together. Warner Brothers hired us to write a science fiction action movie. It was while we were doing that that we figured we shouldn’t be a writing team.”

Addica is more emotional talking about the experience. “It was like we were married, man; and when we broke up, it was awful,” says Addica. “It was very difficult. But I have nothing negative to say about the guy at all.”

Yet still they continued to work on Monster’s Ball, and it fell to them to defend the integrity of their script. At times the story was tantalizingly close to production. Fine Line gave the script to DeNiro who wanted to play Hank, and DeNiro passed it to Sean Penn who wanted to direct. But that pushed the budget of the film far too high. Producer Lawrence Bender took an option on it next but that led to another dead end.

Finally, producer Lee Daniels came into the picture. Daniels wanted to return to the writers’ original ending which Addica recalls as “a big selling point.” Daniels brought the film to Lion’s Gate Entertainment, and director Marc Forster was attached.

Though the film’s acting is uniformly excellent, the most memorable performance comes from Halle Berry who pursued the role of Leticia from the moment she read the script. “She came in and said ‘I know you guys don’t want me in this movie. You think I’m just a big pretty face, but I want this part.’ And she proved everybody wrong who thought that maybe she couldn’t do it.”

Leticia and Hank are unlikely lovers in many ways. Of course, they’re an interracial couple in a small Southern town, and

In the end, Addica and Rokos didget to play roles in their film thoughyou’ll have to look closely to spotthem. Rokos plays the prison wardenwhile Addica plays a prison guard.Yet today, both Addica and Rokosare working—more as writersthan as actors.

Hank has recently executed Leticia’s husband. Emotionally they’re equally different; Hank is repressed and inarticulate while Leticia seems to go from outburst to outburst.

With so many outbursts, yet so few words written into the script, Berry’s role demanded a lot of improvisation—including the sex scenes. It’s something that Addica heartily endorses. “Some of our dialogue is so sparse that it almost begged to be improved at points. I was hoping they’d improve upon it. I’m sure they made a lot of improvements where it needed it.”

In the end, Addica and Rokos did get to play roles in their film though you’ll have to look closely to spot them. Rokos plays the prison warden while Addica plays a prison guard. Yet today, both Addica and Rokos are working—more as writers than as actors.

“I feel more like a failed actor than a successful writer,” laughs Rokos. “I’m hoping it will help me get some acting work in the future, maybe. When Monster’s Ball took off the way it did, I got so busy that I haven’t really acted in the last couple of years.

“It’s just an irony of show business,” continues Rokos. “The script helped our writing careers instead of our acting careers.”

Indeed, the pair could be one of the hotter writing duos in Hollywood right now—but they agree that they’ll never write together again. They speak highly of each other, but Addica puts it very clearly: “We’re not working together, and we’re not going to work together. We’re not enemies or anything, but we don’t hang out, and we don’t talk.”

Nor is Addica certain that he can write many more such intense dramas as Monster’s Ball.

“It’s just so difficult to bare yourself like that,” he confesses. “To get to the depth of something that has any real meaning and weight, that can move people, you have to really be honest. Patrick Shanley said an actor has to work from the darkest part of his soul, and I think that’s true for all artists and all art forms. To get to that can be very painful.”

But Addica and Rokos stayed together when it counted, working through the pain while Monster’s Ball was in development, and while they heard so often thatheir script would never get made.

“Milo and I never accepted that,” says Rokos. “If something fell apart, we didn’t even once suggest chucking it and giving up. It was always ‘let’s call someone else.’ We didn’t give up. We were tenacious f***ers, and it paid off.”

Originally published in Script Magazine January/February 2002

- From Script to Screen: 'The Hours'

- Script Angel: Networking Tips for Screenwriters

- Balls of Steel: How to Write a Script That Sells Itself

Get help on creating the best script concept with

Writing High Concept Screenplays That Sell