When Mike Nichols died, in 2014, it was difficult to quantify just how much he’d contributed to American culture in the preceding decades. His collected credits are one of the greatest sources of “He did that?” in the history of show business. To name just one starting point: Through its depiction of quarter-life ennui in the face of a society whose values, priorities, and aspirations could be summed up in one word, Nichols’ 1967 film The Graduate was embraced by the baby boom generation and the aspiring auteurs enrolled in then-burgeoning film schools. But these were not, strictly speaking, Nichols’ people. Before their parents were even thinking about doing something about the Nazis, Nichols was already escaping Berlin, a 7-year-old of Russian and German Jewish ancestry put on a boat to New York alongside his kid brother, Robert, knowing only two phrases in his destination’s national language: “I do not speak English” and “Please do not kiss me.”

Even before The Graduate, Nichols had defied Jack Warner and the old Hollywood guard by making an Oscar-winning version of Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? in then-unfashionable black-and-white. It was an auspicious cinematic debut that followed an 18-month period in which he’d mounted four consecutive Broadway hits (resulting in back-to-back Tonys for Best Direction Of A Play), which was itself an encore to the work he’d done as part of Chicago’s Compass Players (the forerunner to The Second City) and the headlining, Grammy-worthy double act he’d spun out of that troupe with Elaine May. And that all accounts for merely the first decade of a career that weathered creative peaks and commercial valleys all the way into the 2010s. So how in the hell are you going to condense all that into an obituary?

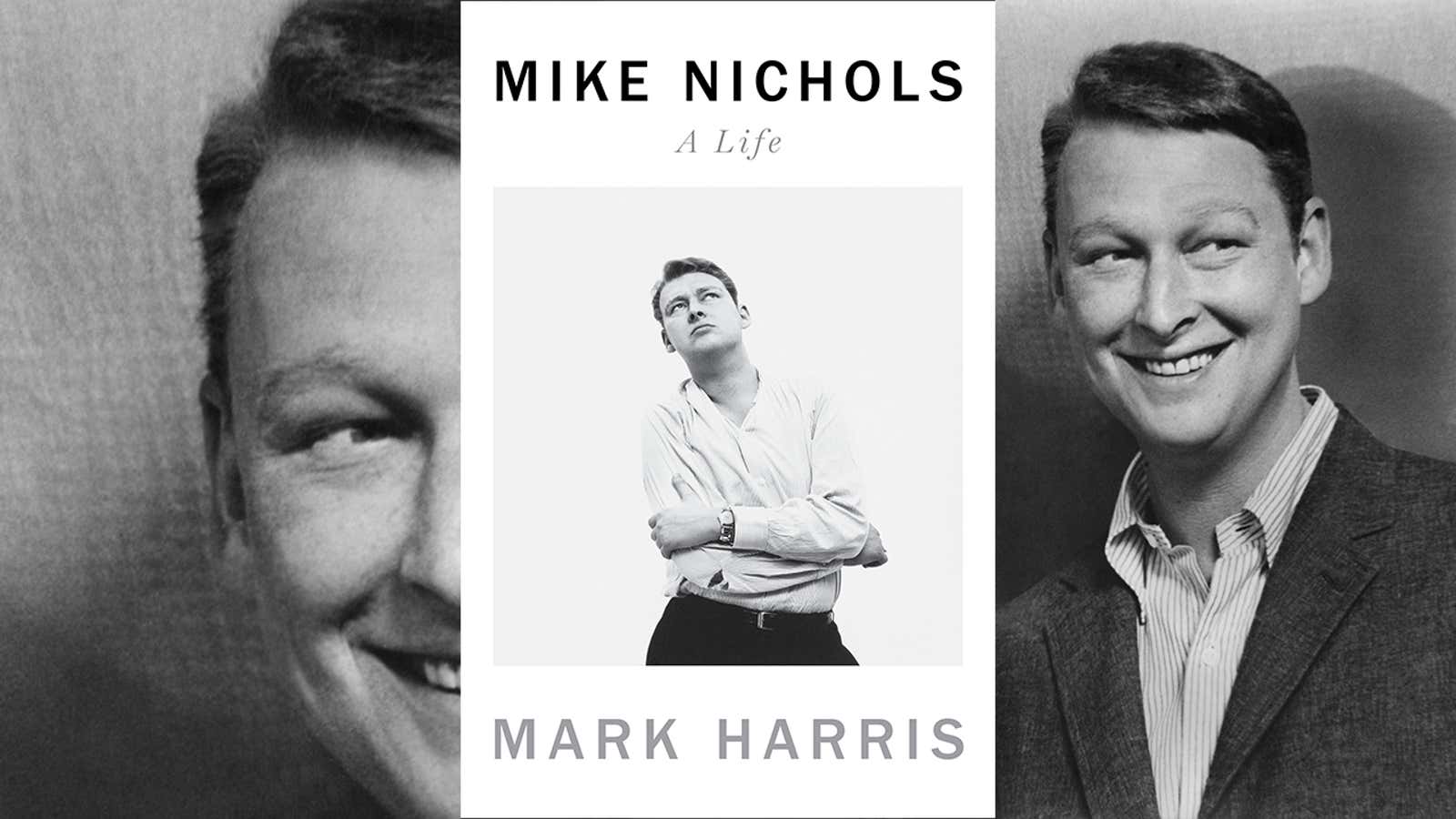

Nichols’ life and work previously inspired a book-length oral history, a pay-cable documentary, and an episode of American Masters directed by May, but there’s still enough material to fill out 688 pages of Mike Nichols: A Life, the new biography by veteran entertainment journalist Mark Harris. The author had a bit of a head start: He’d already covered The Graduate in his 2008 chronicle of the Best Picture race at the 40th Academy Awards, Pictures At A Revolution. Before that, he and Nichols became acquainted through Harris’ husband, Tony Kushner, whose play Angels In America inspired the last unequivocal triumph of Nichols’ career (give or take a Spamalot). Mike Nichols doesn’t rest on this prefab access; it’s built atop a foundation of more than 250 interviews with the people who knew, worked with, loved, and maybe even occasionally hated Nichols. May is here, remembering the first comedy sketch they ever devised, a dud in which it hadn’t occurred to either of them that there was no good way to dramatize someone not being around to pick up a telephone. Meryl Streep remembers attending the catered, everyone’s-invited reviewing of a day’s footage on Silkwood. (“I’d practically had to present my SAT scores to get into the dailies of The Deer Hunter,” she says.) Every time Stephen Sondheim pops in, it’s a reminder that Nichols’ social circle was composed of Bernsteins and Styrons and Avedons—just a bunch of 20th-century masters hanging out together, wondering why Nichols had gotten everyone so interested in Arabian horses.

Harris is a savvy enough reporter and critic to tell when stories like the young Nichols’ limited, transatlantic vocabulary probably became truth through retelling; he’s also keen enough in his role of biographer to recognize when a subject simply wouldn’t cooperate with the conventions of the biographical form. “All the shit was in the beginning,” goes the archival quote that moves the narrative from Nichols’ childhood to his education and theatrical training in Chicago. “Let’s start now.” With help from Nichols, Harris has sidestepped that pitfall of even the most engrossing bio: the endlessly deadening chapters that’d be better left to the “Early life” section of a Wikipedia page. It’s a good indication that, despite occasionally needling quirks like the telegraphing of fateful meetings with future collaborators, Mike Nichols is a cinderblock of a book whose weight is never felt in the reading.

Speaking with so many members of the informal repertory that stocked Nichols’ theatrical work in the ’80s, ’90s, and ’00s—Glenn Close, Cynthia Nixon, and David Hyde Pierce, to name a few—Harris conveys a portrait of director-as-collaborator. He might not have always adhered to his professed “no assholes” rule, but Nichols was, as those who worked with him recall, more apt to guide his casts with an anecdote or analogy than an instruction or a command. It’s a technique recognizable from a story told early in Mike Nichols, in which Nichols describes a note from Actors Studio head Lee Strasberg that began “Do you know how to make fruit salad?” as “The best thing about acting I’ve heard.” The arc of the book is one of many rewarding, evolving, and revolving partnerships in which such metaphorical questions could’ve been asked, from May to Neil Simon to Buck Henry to Jules Feiffer to David Rabe to Nora Ephron and back to May again.

They are complements, and they are counterparts. Through quotes and commentary, Harris draws out the many parallels and mirror images that would populate Nichols’ work. Flush with early success, Nichols and Simon each felt they had a finger on the cultural pulse—until the moment the culture proved them demonstrably wrong. The tensions that racked the sci-fi comedy bomb What Planet Are You From? are diagnosed as Nichols seeing in star Garry Shandling all the insecurities and false inadequacies he’d smothered in the extravagant trappings of wealth and success. To jump off from a theory floated by the Blank Check podcast, Ephron’s directorial career was marked by an alternating between effervescent romantic comedies that connected with audiences (Sleepless In Seattle, You’ve Got Mail) and expressions of her caustic authorial voice (Mixed Nuts, Lucky Numbers) that did not. It’s an almost photo-negative version of an impression given off by Mike Nichols: Having established a reputation for biting commentary and lampooned social niceties, the version of Nichols that critics and moviegoers preferred was nowhere to be found in the saccharine, second-chance schmaltz of Regarding Henry. Somewhere in between lies Heartburn, an adaptation of Ephron’s novel that makes a meal of her divorce from journalist Carl Bernstein, which Harris calls “perhaps [Nichols’] most underappreciated comedy.”

In the shadow biography of May that weaves in and out of Mike Nichols, Harris acknowledges that the do-overs afforded again and again to Nichols were never extended to his first creative other half—particularly not after her own Day Of The Dolphin-sized flop, Ishtar. It’s no great leap for a biographer to treat Nichols’ relationship with May as prominent as his marriage to Diane Sawyer, or his connection with his children—even accounting for their time apart, it outlasted his three other marriages. Any insinuation of sexual tension between the two is made explicit in a recounting of their abortive, possibly-exaggerated-in-hindsight attempt at coupling during their University Of Chicago days; whatever romantic feelings that lingered eventually resulted in the mutual platonic attraction that would pull them into a production of Virginia Woolf or a filmmaking partnership through the ’90s. Getting May on the record stands as one of the book’s major accomplishments, one that calls out for a full-fledged follow-up and affirms this most crucial of connections—“I the darkness, you the light,” as May once described it to Nichols. He was moved to tears and debilitating fits of laughter by her; she was the person he trusted so deeply that he didn’t mind when she worked into the act the fact that he’d lost all of his hair at age 4.

Nichols’ wigs and false eyebrows were a matter of public record later in life; his drug use, less so, to the extent that the first published excerpt of Mike Nichols went viral not solely on the strengths of Mandy Patinkin’s memories of being fired from Heartburn, but also thanks to it mentioning Nichols’ circa-1986 crack habit. (The man’s been dead for seven years, but he’s still the topic of New York Post gossip.) If that’s the sort of publicity Harris wasn’t hoping for, it’s because that’s not the type of book he’s written. In its understated prose, Mike Nichols treats these dalliances with a casualness approaching Bob Odenkirk in the Mr. Show lie-detector sketch: “It’s crack—it gets you really high.” In a lengthy footnote, Harris also states he found no evidence to confirm the relatively recent assertion that Nichols and photographer Richard Avedon had a decade-long love affair. (“If I had, I would not have considered it to be embarrassing, scandalous, or necessary to suppress—nor was I ever asked to,” he writes.)

Anything larger-than-life is reserved for the professional Nichols. The author gives Nathan Lane an appropriately theatrical entrance into the chapter on The Birdcage; the making of Catch-22 becomes a life-imitating-art farce in which the fire and noise of Joseph Heller’s anti-war satire overwhelm Nichols’ visual ambition and stately long takes. (It’s still worth seeking out, at least, for crackerjack staging of scenes like Major Major Major Major’s meltdown over his mistaken promotion.) The net is cast wide for secondary sources as well as primary ones: For the last word on Catch-22—once a hotly anticipated Vietnam-movie-that’s-not-about-Vietnam that failed to get a grip on famously slippery source material and had all its thunder stolen by M*A*S*H—Harris throws to a particularly stinging MAD magazine parody.

And what more fitting lens through which to view an artist so adept at bridging high- and low-brow? The picture of Nichols that comes through most sharply across nearly 700 pages is of someone who lived to create and help others create. “It’s just that this is what you do,” Lorne Michaels recalls Nichols saying of an unyielding artistic drive that seemed to baffle studios in the ’90s. The book makes minimal show of establishing Nichols as an innovator of many showbiz types and conventions that persist to this day. Everybody talks about the groundbreaking use of Simon & Garfunkel tracks in The Graduate, but where outside of Mike Nichols are you likely to find, in 2021, Nichols and May being given their due for successfully locating the vein of neurosis in sketch comedy? Or the sincere, un-mugging way those sketches came by their jokes, an approach that carried over to Nichols’ comic stage and screen work to a degree that they taught a whole generation of performers and directors the importance of never going for the laugh at the expense of character or story. The bio is not such an act of flattery that it prevents the drawing of lines from Nichols to less honorable trends: stunt-casting movie stars in Broadway productions, for example, or great comedic minds desperately grasping at “serious artiste” status. (For the double whammy, see the chapter on Nichols’ production of Waiting For Godot starring Steve Martin and Robin Williams.)

Mike Nichols secures enough monuments to talent that there’s something beautiful in Nichols and May’s biggest innovation being lost to history. Named for the playwright of Six Characters In Search Of An Author, “Pirandello” was “the only major Nichols and May routine that they never chose to film or record.” A bit of meta-theater that seamlessly transitioned between argumentative scenes until it appeared that the actors were in fact sniping at one another, “Pirandello” kept audiences guessing whether they were witnessing two characters having it out or if the volatile, excessively witty (and capable of great interpersonal cruelty) duo were combusting in real time. Harris’ reconstructions, filled in by May, make it sound utterly transfixing—an opening to the mindfucking work of Edward Albee, Samuel Beckett, and Tom Stoppard that Nichols eventually put his stamp on. You’ll never get to see it. The book will suffice.

Author photo: Penguin Random House