The arrival of anything by post was significant during the pandemic lockdown but, for the writer Michael Frayn, the contents of one envelope were particularly welcome. “Theatre had stopped and my income had dried up, so I was astonished when a large cheque arrived for amateur performances of Noises Off all over America. People are putting it on all the time.”

Since 1982, when Frayn, 89, first staged his fast-paced comedy about actors in a workaday farce, it has become a staple crowdpleaser around the world. This month, a touring 4oth anniversary production brings the show home to London’s West End for a triumphal fifth time, now at the Phoenix Theatre.

“I can’t quite understand it. Local theatres in Germany seem to be doing it continuously,” said the playwright. “In Finland, they used the idea that a company in the north were putting on an effete farce sent up from Helsinki, while in Barcelona a controversial production had a Catalan company putting on a Spanish-speaking show.”

On Broadway, however, producers have so far stuck to Frayn’s original English setting, which sees a troupe of jobbing performers simply “putting on some dreadful sex comedy”.

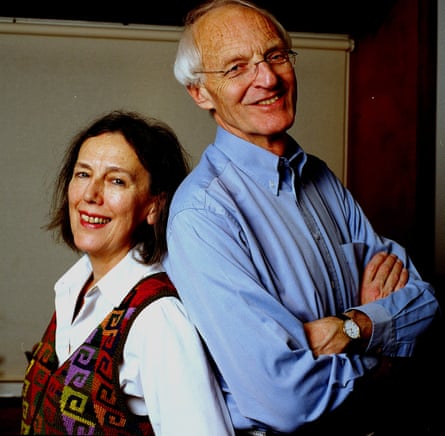

Funny shows can age quickly, but when the mechanics are as finely wrought and the human confusion as universal as in this, Frayn’s biggest hit, the length of the laughter appears limitless. Very few changes to the dialogue are ever made. “I am amazed that people are still prepared today to put on a play in which a rather dim young actress spends all evening in her underclothes,” said Frayn, who lives in Richmond with his wife, the acclaimed biographer Claire Tomalin.

The author, who wrote for the Observer in the late 1960s and early 70s, has since produced a string of celebrated works, including the serious plays Copenhagen and Democracy and the admired novels Spies and Towards the End of the Morning (the latter, set in a newspaper office, is especially loved by journalists).

Usually, he says, the decision to tell a story on stage or in a book comes early. “Ideas immediately suggest one thing or the other, and Noises Off, obviously, had to be a play.”

The show’s first London cast was led by the late Paul Eddington, known for The Good Life and Yes Minister on TV, as the show’s beleaguered director, Lloyd Dallas. “He was terribly good,” recalls Frayn. “Claire remembers the management had to hold the curtain for 20 minutes at the beginning of the second preview because there was such a queue for tickets at the box office. Word had got out that we had something.”

But the play’s birth had been as complicated as its layers of cross-purposes might suggest. The idea first came to Frayn while watching, from behind the scenes, a one-act play he had written for Lynn Redgrave and Richard Briers. It was a pastiche of a five-character farce which, with a cast of just two, involved silly quick-changes and theatrical illusions. “I thought I would like to write a farce seen from backstage like this. It was a simple thought to have, but it turned out to be fiendishly difficult to do,” he says.

His notion of a staging a play which deliberately unravels before the audience’s eyes has proved highly influential. Not only did it permanently mess with theatrical expectations, it also arguably laid the groundwork for a string of spoof fly-on-the-wall formats on television, each revelling in the background mishaps of, say, a ministerial department in The Thick of It. More directly, it may have inspired the The Play That Goes Wrong series, a popular stage and television franchise that Frayn says he is ashamed not to have yet seen, adding: “But I am told they are very good.”

The first version of Noises Off, which takes its title from a common stage direction, was a one-act affair put on for a charity event. Renowned stage producer Michael Codron saw its potential and commissioned a full-length version. “I could see a way to do it by separating it out into three acts so that I was not trying to show everything simultaneously,” says Frayn.

“First, you needed to see the play and get to know the cast, then we needed to see what went on backstage between the actors, and then finally you see what complete mince is made of the play. But it took me a long time.”

after newsletter promotion

Frayn says the play eventually functioned only after collaboration with the Australian Michael Blakemore, his friend and “one of the greatest directors in the world”. “When we do a play, he makes me read the text out, which is an extremely painful experience because I have no acting ability whatsoever. I can’t even hit the right stress in my own lines. He sits there, not laughing or responding, then asks very stupid questions. Stupid questions are always the best questions.”

The playwright was convinced actors would find it too tricky to learn all the variations, in particular the repeated actions. “I thought: ’No one is ever going to do this’ – and indeed it is extremely difficult. Actors have to sort of start the mime over again each time in their head. They also have to play a lot of it to the back wall of the theatre, while we watch from behind. In the end, I thought: ‘If I can just get it finished, then I can forget about it.’ So I was amazed when Michael Codron still wanted to do it, suggesting some helpful changes.”

Frayn admits he once cultivated a disdain for theatre, the form of entertainment that now largely supports him. As a newspaper columnist he frequently mocked it: “I would say how embarrassing it was: the whole idea of people standing around in artificial groups, speaking in loud voices. I was slowly drawn into it at the end of my 30s – late for a dramatist.”

Today, his hit comedy, staged in Warsaw, Budapest, Bucharest, Tallinn and even Vienna’s prestigious Burgtheater, is Frayn’s “life support system. Copenhagen does quite well, but nothing in comparison. It is my Mousetrap.”