Actors are practised at charm, so when Matt Smith barrels into the room, wearing a striped sweater and swinging his bag like the Artful Dodger, I try hard to remember the pinch of salt with which I should take everything that he says. But it’s no good. Half man and half puppy, he’s so friendly, it fairly knocks me over. Am I warm enough? Where have I come from? He’s so sorry he is late (he is not late). “Bring it in!” he shouts, enveloping me in a bear hug when I hand him a book I’ve brought for him. “A present? You didn’t need to do that!” As for the small collection of chocolate biscuits someone has kindly left for us on the table at which we will sit, it provokes an expression of such delight, it could be myrrh or frankincense or – I don’t know – the kind of fabulous watch he might model for a men’s magazine. Biscuits? What next? The moon? In fact, what’s next is a cup of tea, and though he’s “a real pedant” about tea – when he was on Desert Island Discs, his luxury was an indefinite supply of English Breakfast – this, too, enraptures him. Oh, the luxury of a fresh, malty brew.

It’s early in the morning. He and I are in the hall of the Victorian chapel where he is rehearsing a new production of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People. High above us is a gallery with elaborate wrought-iron balustrades: a place, perhaps, from which men in hats and women in twin-sets once watched choir practice, or waited for Sunday school to end. But otherwise, the scene is quite boring. Apart from the words “a day later”, chalked by an unseen hand on a blackboard, I can find no clues as to what might be happening here: no helpful props; no signs of any sturm und drang.

What is his iconoclast of a director, Thomas Ostermeier, like to work with, I ask. Does he break people down, only to build them back up again?

Smith laughs. “I did compare him [in my mind] to José Mourinho: sort of like one of the mavericks of football, but…” What? Is he more like Roy Hodgson, or something? More laughter. “No, but he is a really nice man. When he turns the screw, he’s very detailed and particular, but he’s also very open and conscientious about how you’re feeling.” Is Smith allowed to tell me (I wrinkle my nose a bit) about his process? “Well, I don’t know how much Thomas likes that stuff to be revealed. But it has been very interesting, and yeah, he was the great selling point of doing this for me.”

In case you’re wondering, Ostermeier is a German director well-known in Europe for his “canon-mauling” aesthetic when it comes to the classics. Since the late 90s, when he was a wünderkind who believed those over the age of 40 had no business running theatres, Ostermeier has been merrily applying his form of “capitalist realism” to major playwrights, reimagining the work in ways that have brought him acclaim throughout the world. But while he has toured plays to the UK before – in 2014, a German production of An Enemy of the People played at the Barbican – this is the first time he has worked with a British cast, a fact that Smith rather sweetly believes may have helped him to land the role of Thomas Stockmann, the medical officer of a small-town spa who discovers its water is contaminated and goes on to make one of theatre’s more notable political speeches, an attack on the liberal majority and its vexed relationship with the truth.

“I got an email, as you do,” says Smith. “Tuesday afternoon, or whatever. Ah, a play. That’d be interesting. Ah, Ibsen. That would be cool. And then: Thomas Ostermeier, do you want to meet him? I was like, excuse my language, fucking yes, yes I do! I’d been a big fan of his for years. I’d seen his Richard III, and I knew of his relationship with Lars Eidinger, an actor he has collaborated with for years. So we had lunch together, at one of my favourite restaurants, and I was just really struck… He’s sort of impressive. I’d always thought that if he ever did work in London, I’d check in and go and see it, because that’s the kind of theatre I want to be engaged with: the stuff that tries to push things to the edge of… everywhere. I mean, what he has done at the Schaubühne [a theatre in Berlin]… the culture he has developed there!

“Anyway, I was in luck. I’m not sure – I don’t think he’ll mind me saying this – that Thomas had a great knowledge of English actors or their work. But he had watched The Crown [the Netflix series in which Smith played – brilliantly – Prince Philip for its first two seasons], and he’d enjoyed it. What was interesting about the meeting, though, was that we got discussion of the play out of the way quite quickly, and then we talked about life and everything else. We both love Brazil, so we talked about that. And then I did that thing afterwards where I phoned my agent and I said pretty much there and then that I was in, because I think that’s what you should do if you’re lucky enough to get in a room with someone you really want to work with.” Crikey. But didn’t Smith always used to insist he was a terrible ditherer? I read somewhere that even after he’d accepted the part of the Doctor in Doctor Who, a role that would change his life, he wasn’t sure he’d done the right thing. “Well, I’m trying,” he says, a touch of Noël Coward in his voice. “One hopes to evolve as one hits seniority, on whose middle-aged door I am now knocking.” (For the record, he’s 41.)

Ostermeier’s An Enemy of the People has a modern setting, and comes with a paint fight and a performance of David Bowie’s Changes (Smith’s character is in a band, who rehearse on stage). The director is also retaining the big moment, seen in productions elsewhere, when Stockmann’s opponents ask the audience for a show of hands – is he right or wrong, politically speaking? – before inviting them to pose any questions they have. Smith goes on: “What grabbed me about Stockmann is the idea of playing someone who’s on the right side, saying the right thing and fighting for the truth, but who is ultimately like a star turning into a black hole, enveloping himself in his own ego and velocity and opinions. And then, for people to be able to put up their hand and say: I think you’re like this, and the world out there is like that… They’ll actually be able to talk to him.” Won’t that be terrifying? Such jeopardy, it seems, is half of the point. “I hope people do ask questions. It’s such a volatile time. You only need look around to see all the steam coming out of people’s ears, and the theatre has always been a space historically, almost like a church, where a person can go: look, I feel like this. I’m genuinely interested to know where the audience feels the morality of the play lies.”

Why do actors with TV or film careers return to the theatre? Week one is doubtless thrilling, but what about week seven? And the pay, my dears!

“That’s a good question,” says Smith. “I was talking about this, as one does, to the wonderful actor Freddie Fox, who is not only astoundingly beautiful but also a creature of the theatre, and he said: ‘Well, darling, you know, it’s where one sharpens one’s tool.’” We hoot at the innuendo, and then he says: “But he’s right, of course. What you say about it being repetitive, that’s one way of looking at it. But Lindsay Duncan, another wonderful actor I did a play with, said to me it’s about being consistent and developing, and that… robustness.” The challenge is what he relishes – that and, in this instance, a change of pace from the Games of Thrones prequel House of the Dragon, the second series of which he shot last year (Smith plays Prince Daemon, in a wig that makes him look, as I said when I reviewed it, like he’s on tour with Sigue Sigue Sputnik).

But theatre isn’t without its anxieties. Like many actors, he is concerned about the ability of the audience to focus. How distracted people are. “I’m not a guy who would even take sweets into a cinema,” he tells me. “So, yeah, I do worry about noise. But I think there’s a cultural thing where at home we watch a movie or The Traitors or whatever, and at the same time, we’re also doing this…” He mimes scrolling a mobile phone. “Surely to God we can concentrate and suspend our disbelief for two hours – if it’s an interesting enough play, and part of that is up to us, keeping people interested.” He hopes a younger audience will be drawn to An Enemy of the People. Post-Covid and in the midst of a cost of living crisis, its message about the dangers of privileging economics over community are more relevant than ever. But he also worries that some simply won’t be able to afford it. “I hope we’re not pricing young people out,” he says. “I mean, the theatre is so much money, for all of us. You sort of go: I could fly to Milan or Amsterdam [for that].” His eyes (round and deep-set, they make me think of a couple of Maltesers) suddenly widen. “That’s not to say: don’t come. Please do come. But it is true.” He smiles. At moments like these, promoting a play is almost as much of a high-wire act as performing in one.

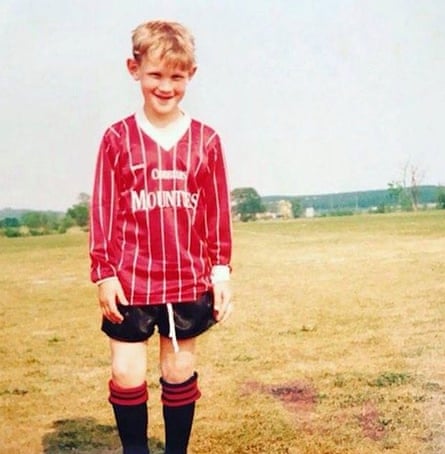

Smith was not destined to be an actor. Football was his thing. He was born and grew up in Northampton, where his dad ran a plastics company, and his mum worked in promotions (he has an older sister, who trained as a dancer). He was, by his own account, a hyperactive child – an energy he maintains to this day – but also a determined, hard-working one. He played for the youth team of Leicester City (he was captain), and loved every minute: the early starts, the muddy pitches, all of it. But then, catastrophe. He developed spondylolysis, a kind of stress fracture. Suddenly, he could no longer play.

Is this still the case? Are there five-a-side games with his mates nowadays?

“I wish! But no, my body won’t facilitate that. I’m just an avid consumer [of football] now. My team – we’re having a bit of a nightmare at the moment – is Blackburn, like my dad’s. God bless him [his father died in 2021], I remember how he refused to buy the papers if Blackburn had lost, and how it would ruin the next hour of a Saturday afternoon when they did. I build my whole weekend around football – the game, and then Match of the Day – and I’m such a fan of England. I went to Russia [for the World Cup], and I watched all of the Euros.”

Looking back, what he learned on the pitch stood him in good stead for acting. “I think my dad instilled hard work in me: you know, the idea that you should always work harder than the person next to you in a team. He was from the north, and hugely loving, but there was a toughness in his love, which I feel really grateful for. I am hard-working, but I’m also better with structure in my life. That’s a good environment for me.” Home grounds him, even now: he still has mates from those days. “Yeah, my two best friends, Alex and Nick. We lived in the same street as children. They’ve been very important to me in my life. Especially when you get a job like Doctor Who, which thrusts you overnight into a completely different atmosphere. It’s quite discombobulating. Suddenly, people recognise you.” When Doctor Who came along – he was in the role from 2010 to 2014 – they were prepared to take the piss out of him “consistently”. But they also supported him (they are not actors). “They come to see everything I’m in, and they’re really honest.” One of them saw him in American Psycho, a musical adapted from Bret Easton Ellis’s novel that opened at the Almeida theatre in London in 2013. “I said to him: ‘What did you think, mate? How was my singing?’ And he was, like: ‘Yeah, everyone else was better at singing.’” I vaguely nod my head – I saw it, too – and he shouts: “Don’t agree with him!”

A drama teacher, Terry Hardingham, encouraged him to act, though at first he was reluctant. (This might have been because, as a younger boy, he’d suffered from a stutter, one he eventually cured with hypnosis.) “I was a footballer. That was not for me.” But the teacher persisted, and Smith caught the bug. In the last year of school, he joined the National Youth Theatre, “a wonderful thing for young actors”. At the University of East Anglia, he kept up with it, and through it, he got his agents, and through them, an audition (successful) at the Royal Court. His university tutors weren’t happy, but he did the job anyway, which is how the playwright Simon Stephens, who saw it, came to cast him in On the Shore of the Wide World at the Royal Exchange in Manchester (the cast included Siobhan Finneran). “I was doing creative writing and drama at university, and I was in my final year, so at the same time I was writing 12 final poems and a story. I went back and did my dissertation and exams in a week. It’s the only time I’ve ever drunk coffee.”

Didn’t his parents want him to have a proper job?

“You know, the element of risk didn’t bother them. What I’m so grateful for is that on some level, conscious or not, they had faith in me.” He misses his father painfully. “I miss the company,” he says. “He was so… you know. I miss that older male. We were so close. My friend Nick lost his dad at 21, and he said to me, you know, the next two years are going to be a blur, and looking back, they sort of have been.” We talk about the business of losing a parent. “[At the time], it doesn’t feel like the horrible bits are really happening. It’s a stasis of anxiety and stillness, but your feet are moving and your arms are moving, and you’re just wallowing in this sort of… murk. Praying and hoping and waiting.”

What about his mum? “Oh, I have a good laugh with my mum. She’s doing well. She had a tough time after my dad. It’s very destabilising when you lose the… he was sort of the centrepiece. But she’s out there now, grabbing life. I’m proud of her, and she’s hilarious.” Will she be there on the first night of An Enemy of the People? He gives me wry look, pursing his lips comically. “No. She will be on a cruise. She will be in Fiji.” He laughs fondly. When’s he going to settle down? “Oh, my mum asks me that every day. I don’t know, I don’t know… I’m in no rush at the moment.” He won’t tell me if he’s single or not (I don’t really blame him), but the “anchor” of his life is his Irish terrier, Bobby. “Dogs are a wonderful thing.”

After An Enemy of the People, he will begin shooting a TV adaptation of Nick Cave’s 2009 novel, The Death of Bunny Munro; he will play the titular Lothario, a womaniser and alcoholic. “It’s out of the frying pan and into the fire… I’ve only met Nick Cave once, but I think he said [about the adaptation]: ‘Finally, someone has had the balls to tell this unholy tale.’ Bunny Munro is a character who it’s near impossible to get on board with. I was in America recently, and I met a woman who said: ‘I work with people who are really, really bad people, in prisons basically – and there is not a man on Earth I despise more than him [Munro].’”

He wants to “re-evaluate” his work ethic. “I want to get back to the frame of mind I had when I was younger, when the level of focus was pretty laser.” The bigger the challenge, the more likely this is to happen. Fame doesn’t really interest him. It opens doors, but in the end, as he puts it, “you can only be your Hamlet”. Worrying about what your peers are doing – who’s up, who’s down – won’t get you anywhere. “I’m a firm believer in trying to commit to keeping things as everyday as possible. I had a nice talk with the cab driver on the way here. ‘What are you up to?’ he asked. I was listening to Talk Radio. I said: ’What do you mean? I’m off to work.’ And he said: ‘I know that, but what are you doing?’ I was, like: ’Oh, sorry mate, of course…’”

People are starting to arrive for rehearsal; there is bustle outside, the sound of a spell being broken. I don’t know why – this isn’t the kind of thing I usually do – but in the last minutes before he has his photograph taken, I ask him to tell one bizarre thing about himself that no one knows. He thinks for a minute, hesitates slightly, and then he says: “I have to touch something red every time I see a Royal Mail van.” Blimey. How long has this being going on? “Twenty years – and there are a lot of Royal Mail vans.” I tell him he should save himself the trouble, and carry something red with him all the time, but I get the impression he thinks this might be cheating – and then he leaps up, insists on a selfie, and disappears, leaving me to ponder the fact that, if the Royal Mail does ever reduce its service to three days a week, there is at least one customer who might be quite relieved.