Supported by a Create NSW Arts and Cultural Grant – Old Parramattans

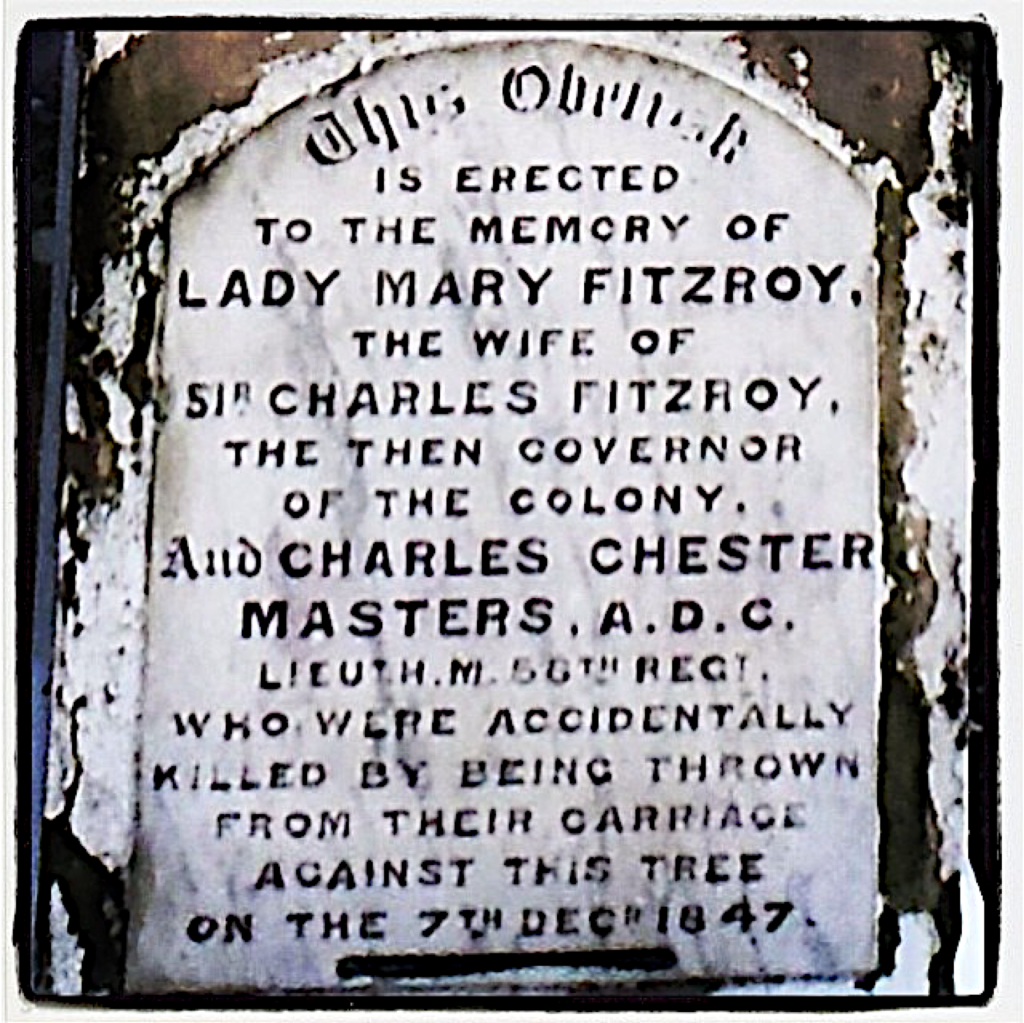

In Parramatta Park, not far from her burial place in St. John’s Cemetery, is a monument dedicated to Lady Mary FitzRoy marking the spot where she was tragically killed in an accident in December 1847. The white obelisk, now enclosed by an iron fence, reads:

Left: The Lady FitzRoy Memorial in the World Heritage listed Parramatta Park, near the George Street ‘Tudor’ Gatehouse and Murray Gardens. Michaela Ann Cameron, “Lady FitzRoy Memorial, Parramatta Park,” St. John’s Online (2014) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) © Michaela Ann Cameron; Right: This Obelisk is erected to the memory of Lady Mary FitzRoy the wife of Sir Charles FitzRoy, the then governor of the Colony. And Charles Chester Masters, A.D.C. Lieut. H.M. 58th Regt. Who were accidentally killed by being thrown from their carriage against this tree on the 7th Dec 1847. Michaela Ann Cameron, “Lady FitzRoy Memorial, Parramatta Park,” St. John’s Online (2014) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) © Michaela Ann Cameron.

Lady Mary FitzRoy was a woman of impeccable breeding from the British aristocracy who came to Australia with her husband, Governor Sir Charles FitzRoy. She was believed to bring a sense of grace and refinement to the Colony of New South Wales and countered the sometimes negative reception of her husband. This extremely well-travelled woman helped to shape the colony through her contributions to polite society and her genuine care for those in need. The huge outpouring of grief that gripped the colony after Lady Mary’s abrupt death in this carriage accident is comparable to that of another Lady of the people, Princess Diana (a distant descendant of the FitzRoys), who died in a motor vehicle accident in 1997. The monument in Parramatta Park that was erected nearly forty-one years after her death is testament to the enduring legacy that the wife of the tenth Governor of New South Wales left to the colony, despite spending a mere sixteen months in Australia.

Early Life

Lady Mary FitzRoy was born Mary Lennox on 15 August 1790. She was one of fourteen children (the first or second born, sources vary) of the British Army Captain and Scottish peer Charles Lennox, fourth Duke of Richmond and his wife Lady Charlotte Gordon, a Scottish peeress and the daughter of Alexander Gordon, fourth Duke of Gordon.

A marble bust of Lady Charlotte Lennox (née Gordon), the fourth Duchess of Richmond and the mother of Lady Mary Lennox FitzRoy. Joseph Nollekens, Charlotte, fourth Duchess of Richmond (1768–1842), (1812), Public Domain, B1977.14.19, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Video edit by Michaela Ann Cameron.

The Lennox family were descended from Charles Lennox, first Duke of Richmond, the illegitimate son of King Charles II born in 1672 to his French aristocratic mistress, Louise de Kérouaille. The family estate of the Dukes of Richmond is Goodwood Estate in Sussex, and during the eighteenth century they were one of the most powerful and influential aristocratic families in Britain.[1] In contrast, Mary’s maternal family, the Gordons, were a well-known and powerful Scottish land-owning family descended from the Dukes of Argyle.[2]

Mary’s early experiences prepared her for her later role as the genteel wife of the Governor of the British Colony of New South Wales. During her youth she moved to several locations in Europe and the British Empire with her father Charles Lennox. There are very few sources that directly describe Mary’s experiences in her early life. However, from the movement of her parents and siblings we can ascertain that she was witness to several important events of the nineteenth century. In the year of Mary’s birth, her father succeeded his own father as an MP for Sussex and in 1804 he inherited the title of Duke of Richmond after his uncle’s death. During this time, Mary and her siblings were raised at the Goodwood Estate and her sister Georgiana later recalled an idyllic childhood roaming the grounds of this country house.[3]

In 1807 the Duke of Richmond was sworn into the Privy Council (a body of advisors to the sovereign) of King George III and soon afterwards the Duke was appointed as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[4] This was a governing position that made him the most powerful man in Ireland and saw him maintain an English colonial presence in the country. His wife and children joined him in Ireland and their official residence was Dublin Castle during their stay. In 1813 when the Duke’s Irish appointment finished, the family moved to London where the older Lennox sisters came out into London high society during its fashionable London Season.[5] The London Season was a time each year in spring when country gentlemen and aristocrats descended on London for parliament and their families amused themselves by shopping, attending high society functions like balls, and meeting the monarch. Importantly for the Lennox sisters, this was their introduction to the aristocratic marriage market, as their place in nineteenth-century British society demanded they make a suitable marriage match to someone of a similar social standing.

Lingering in the background of much of Lady Mary’s early life were the Napoleonic Wars, a series of conflicts fought between the French Empire and its European enemies (mainly Britain, Austria, and Russia) from 1803–1815. Although Mary had been largely sheltered from these conflicts, in 1814 the family moved to Brussels in Belgium where the Duke of Richmond took up a new military post as Commander of the British reserve forces.[6] By this time Brussels was filled with important British families as the city had become the base for the British Army in 1813. In Brussels the family were central to one of the most famous social events of the Napoleonic Wars: The Duchess of Richmond’s ball. The ball, which has since been dubbed ‘the most famous ball in history,’ was hosted by Mary’s mother Lady Charlotte Lennox, Duchess of Richmond, on the night of 15 June 1815.[7] This was the night before the Battle of Quatre Bras and three days before the legendary Battle of Waterloo, where English forces finally defeated Napoleon Bonaparte and the French. Many key figures at both battles attended the ball, such as the Duke of Wellington and Prince of Orange, and it was during the celebrations that the English were made aware of the advance of the French forces into Belgium under the command of Napoleon.

The ball ended when the Duke of Wellington instructed men to join their regiments and to prepare themselves for battle, cementing the place of this event in the history of Waterloo.[8] Various books and films have since depicted the ball, the most famous being Lord Byron’s ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’ (1812–18) and William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847–48).[9] Though Lady Mary was in Brussels at the time, there are no recollections of her experience of the ball. However, her younger sister Georgiana (who went on to become Lady de Ros) later recalled that ‘I well remember the Gordon Highlanders dancing reels at the ball. My mother thought it would interest foreigners to see them, which it did. I remember hearing that some of the poor men who danced in our house died at Waterloo.’[10] The next morning Mary and her sisters watched many of the men who had attended the ball march out towards the battlefield, including their father and three of her brothers, all of whom were present at the Battle of Waterloo and survived.[11] After the battles the Lennox sisters tended to the wounded.[12]

Marriage

The Lennox family remained in Belgium until 1818 when the Duke was appointed as Governor-in-Chief of British North America (now Canada). Joining him were four of his daughters, Mary, Louisa, Charlotte, and Sophia, and his son-in-law Sir Peregrine Maitland.[13] Just over a year after their arrival, in the summer of 1819 the Duke went on an extensive tour of Upper and Lower Canada, Turtle Island (North America). During this tour he was bitten by a rabid fox and developed hydrophobia (now known as rabies) and died.[14] One of his final deeds was to write a letter to his eldest daughter Mary expressing his pride in her and her siblings.[15] After her father’s death in 1819, Mary and her sisters moved back to England to be with their mother Lady Charlotte.

In middle age Lady Mary was described as being ‘very tall and stout, but has slight remains of the good looks for which she was remarkable in her youth, when in Ireland with her father, the Duke of Richmond, then Lord Lieutenant.’[16] Indeed, such famed good looks are corroborated by a possible painting of Mary and one of her younger sisters, possibly Sophia.[17]

The burgundy-coloured dress and hairstyle worn by Mary date to around 1816–18 when Mary was between 26 and 28 years old.[18] This portrait was almost certainly painted before Mary’s marriage to Charles Augustus FitzRoy, the son of General Lord Charles FitzRoy and Frances Mundy, on 11 March 1820.[19] It is unclear how exactly Mary and Charles met, but Charles, who was a British military officer, politician and aristocrat, was present at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, and also joined her father on his appointment to Canada, Turtle Island (North America) in 1818, so it is likely that they had established a connection while in Brussels.[20] The FitzRoys were also descended from those various extramarital affairs of King Charles II. In 1663 the King’s most powerful and longest-serving mistress, Barbara Palmer (née Villiers), first Duchess of Cleveland, gave birth to a son they named Henry FitzRoy (the surname FitzRoy was traditionally used in England to denote the illegitimate son of a King) and he became the first Duke of Grafton.

Mary’s upbringing as the daughter of a soldier and diplomat, as well as her genteel status, made her a very suitable match for Charles FitzRoy, and their marriage would take her around the world. Just after their nuptials Charles was posted to the Cape of Good Hope as a military secretary and later became Deputy-Adjunct General.[21] Mary accompanied him to what is now the Cape Town region of South Africa and gave birth there to all four of their children—Augustus, Mary, George, and Arthur—between the years 1821–1827.[22] In 1831 the family returned to England and Charles took a seat in the House of Commons. However, by 1837 he wished to return to a colonial post. His requests were granted and in 1837 he was made Governor of Epekwitk, Mi’kma’ki (Prince Edward Island), Canada, Turtle Island (North America), and then Antigua, part of the Leeward Islands in the West Indies.[23] Lady Mary would later regale those in New South Wales with tales of her time in Antigua, including her experience of an earthquake that occurred.[24] By 1843 the FitzRoys wished for a change and began to look to the Colony of New South Wales in Australia. It appears that Mary was instrumental to ensuring her husband’s transfer from the West Indies to New South Wales, because in May 1843 she wrote to her brother Charles Gordon-Lennox, fifth Duke of Richmond, explaining that her husband wished to be transferred there. Later that year Mary wrote another letter to her brother asking if he had spoken to Lord Stanley (the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies) about the transfer.[25] The FitzRoys’ lobbying was eventually successful, as Stanley elected FitzRoy as the tenth Governor of New South Wales in 1845.

CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE. Charles Lennox, 4th Duke of Richmond and Lennox, by John Kay, etching, (1789), NPG D18636. (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). © National Portrait Gallery, London; Portrait of Sir Charles Augustus FitzRoy, (1856), engraving by Samuel Bellin from a painting by G. Buckner, P4 / 27 / FL3287040, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Arrival and Time in New South Wales

Sir Charles FitzRoy, Lady Mary and their son George arrived at Warrane (Sydney Cove) in Cadigal Country on 2 August 1846 in the man o’ war HMS Carysfort. Newspapers across the Australian colonies observed the event stating that the decks of vessels waiting to help tow in the new arrivals ‘were crowded with passengers anxious to be amongst the first to see the new ruler’ and they greeted him with ‘vehement cheers, which were suitably acknowledged.’[26] The following day the new governor and his family were properly received by Sydneysiders and newspapers described Sir Charles as ‘dignified and highly prepossessing,’ a ‘highbred and finished English gentleman,’ and praised his wife and son for their affability.[27] Much was made of the aristocratic background of the new governor and his wife, as they were the first in Government House to hold such high aristocratic connections and trace their respective lineages back to an English king.[28]

A week after their arrival in Cadi (Sydney) the FitzRoys made their first visit to Parramatta in Burramattagal Country on a steamer called the Emu.[29] This was to be the first of many visits to Government House, Parramatta for the FitzRoys and they quickly set about renovating the property, just as Governor Macquarie and Governor Brisbane had also done before them. Using their own finances they transformed the grounds into a ‘vice-regal country seat’ that mirrored those aristocratic estates the couple enjoyed in Britain.[30] Hunting, a pastime of the country gentry in England, was prioritised by Sir Charles who established kennels at Parramatta for his hounds. He also built a racecourse in his Domain.[31]

Although initially celebrated by the people of New South Wales, the lavish aristocratic tastes and sometimes questionable company, particularly of the female kind, kept by Sir Charles and his inner circle soon saw the new governor criticised in the media.[32] Some dismissed him as an ‘aristocratic idler’ and others pointed out the similarities in the governor’s behaviour to that of the vices of his ancestor Charles II.[33] These criticisms, one could say, were inevitable in the colonial setting of New South Wales which was, as Penny Russell has pointed out, ‘marred with petty snobberies and new wealth’ as well as past scandals.[34] A good reputation (defined by manners, birth, and education) and financial capital were vital to maintaining one’s position in colonial society, and admission to Government House was seen to define who was and who was not part of polite or good society.[35] Many feared, then, that in the hands of Sir Charles these polite standards were slipping.

In contrast to the increasingly icy reception of her husband, Lady Mary was rarely criticised in the press. She made sure to steer clear of government matters, and her domesticity, kindly disposition, and attention to duties in the wider community were praised, as they all fitted well into nineteenth-century ideals of respectability, morality, and femininity.[36] All these attributes were also regarded as especially necessary for successful governors’ wives who were expected to represent what it was to be an ‘English lady.’[37] By the time she reached Australia, Lady Mary was fifty-seven years of age and had proven herself as a successful wife and mother. Her duty as the governor’s wife saw her organise many events that were the so-called ‘life blood’ of the colony’s polite society, such as balls, dinners, visits, and other entertainments.[38] She was a fan of dancing and music, and was known to play the polka for others on occasion.[39]

There seems to have only been a few criticisms levelled at Lady Mary regarding her social organising. One was published on 19 October 1846 by a ‘disappointed young lady’ in the Sydney Morning Herald, complaining that the governor’s wife did not ‘invite to her evening party the YOUNG ladies of this place’ but instead the ‘dances latterly consist of elderly ladies, whose dancing days must have passed long since… It is rumoured that Lady Mary is surrounded by a bad clique of ancient dames, and it is feared that those same elderlys [sic] will lead her Ladyship astray.’[40] This criticism was likely due to the fact that the FitzRoys had invited women like Sarah Wentworth née Cox. Although not particularly old at only forty-two years of age, Sarah was regularly shunned from polite social events in Cadi (Sydney) as she was the daughter of convicts and had lived with the explorer William Charles Wentworth as his mistress (even bearing his two children during this time) before their eventual marriage in 1829.[41] Whether the complaint in the Herald was actually written by a young lady, by a young man who was dismayed by only having older ladies of the colony to dance with, or by a critic of her husband who wished to preserve the boundaries of polite society is unknown. But the lack of criticism of Mary is telling of the colony’s respect for their first lady.

Lady Mary also took a keen interest in charitable events such as an annual ‘fancy bazaar’ held by the School of Industry in Cadi (Sydney) held on the Queen’s birthday in May 1847. Annabella Boswell, the young daughter of a prominent landowner in the colony, recalled that when Lady Mary stayed with her family in Guruk (Port Macquarie) in Birpai Country in March 1847 the governor’s wife ‘established herself with her work.’[42] Annabella went on to write that ‘she is most industrious, and is now preparing for the annual fancy bazaar for the School of Industry’ which involved enlisting Annabella and her family to help make work bags, and to knit and crochet various items.[43] All women were taught to sew in the nineteenth century and many were expected to have knowledge of crafts like embroidery, quilt making, and knitting, as these activities were considered ‘fundamental female labour’ that pushed back against the perils of idleness and demonstrated the domesticity and proficiency of a woman as a competent homemaker.[44] Besides her work for the School of Industry’s bazaar, Lady Mary’s knowledge of such skills is also visible in a surviving, albeit unfinished, quilt that she had been making before her untimely death. The hand pieced and sewn quilt is heavily influenced by English styles and the pattern for it was likely taken from pattern books brought to the colony.[45] Lady Mary’s quilt is made of hexagon mosaic patchwork pieces that are of coloured and printed cottons and silks, fabrics that were sourced from throughout the British Empire.[46]

Overall, during her brief time in the colony Lady Mary was praised for her attention to charitable concerns, her genuine compassion for those in the colony, and her special regard for the rural poor.[47] For all intents and purposes she appeared, as Jim Badger has summarised, ‘to provide the perfect exemplar of the ideal middle-class married woman, despite her impeccable aristocratic origins.’[48]

Death

Lady Mary’s time in the Colony of New South Wales came to a tragic end on the morning of 7 December 1847. Summer was wedding season in Cadi (Sydney) and, as the preeminent couple of the colony, the governor and his wife were invited and expected to attend the many weddings held during this time. After spending only a few days in Parramatta relaxing after the wedding of Emmeline Macarthur, the great niece of Australian wool industry pioneer John Macarthur, the FitzRoys readied themselves to return to Cadi (Sydney) to attend the nuptials of a Carlo Connell and Miss Baldock.[49] After their luggage had been loaded onto a river steamer, the couple, the governor’s aide-de-camp Lieutenant Charles Chester Master, and a footman John Gibbs, prepared themselves for the coach journey into the city. Sir Charles was a keen horseman and on this occasion he took the reins of the carriage’s four horses. Newspaper reports later noted that ‘the horses being fresh, ran away the moment their heads were let go’ and galloped towards the domain gate.[50] It soon was apparent that Sir Charles was unable to control the animals and Lady Mary was reported to have stood up in the carriage and screamed at her husband to stop the horses.[51] But it was too late. On the fringe of the estate, in an avenue of oak trees near the Guard house (present-day site of the George Street ‘Tudor’ Gatehouse), the carriage overturned.

Lady Mary was violently thrown against the trunk of one of the trees and the hood of the carriage landed on her chest. Gibbs ran to her aid and later told The Sydney Morning Herald that when he ‘took off her lady-ship’s bonnet; she only spoke once, “Sir Charles,” nothing more or afterwards, and he noted that ‘blood was rushing out from her mouth and ears, and there was a very great deal about her person.’[52] A Dr. George Thomas Clarke of Penrith who was near the scene soon came to aid those in the crash and reported that Lady Mary had sustained ‘great violence on the left side of the face and neck’ and likely died from a fracture to the base of her skull. [53] Lieutenant Master had also been thrown out of the carriage and had likewise sustained terrible injuries. He died later that evening.[54] Sir Charles and John Gibbs were noted to have escaped the accident with only ‘trifling injuries.’[55]

News of Lady Mary’s death took some time to reach Cadi (Sydney), but when it had been confirmed by six o’clock that evening the bells of St. James’s Church and St. Mary’s were tolled, ‘every shop, private residence, and even the meanest hovel closed their shutters,’ and ‘the hoisting of the Union Jack half-mast high at Fort Phillip, were understood throughout the town as confirmatory of the worst.’[56] The day after Lady Mary’s death, shops were asked to partially close until after the funeral.[57]

The double funeral of Lady Mary FitzRoy and Lieutenant Master took place at St. John’s Cemetery in Parramatta at one o’clock in the afternoon of 9 December 1847.[58] Her husband was notably absent, some saying he was too overcome by guilt and grief to attend. Although the interment was intended to be a private ceremony, public outpourings of grief from all the residents of the town reached the cemetery as over 800 mourners joined the funeral procession.[59] Various newspapers reported that the streets of Cadi (Sydney) lay deserted as thousands descended on Parramatta via carriage, river steamer, and on foot to pay their respects.[60] Others reported that there was a total cessation of business in Cadi (Sydney) as ‘all the government offices and public institutions were closed: at least three-fourths of the shops were entirely closed, and the remainder partially so’ in a show of respect.[61] During the procession Lady Mary’s coffin was surrounded by female attendants and was described as having black mountings and being draped in a black velvet cloth. Similarly, the coffin of her ‘luckless companion’ Lieutenant Master was accompanied by soldiers and was also covered in a black cloth.[62] It was one of the largest funerals that the colony had ever seen as many crowded the cemetery with a ‘desire to catch the last glimpse of the coffin of one who had in a few brief months so endeared herself to them.’[63]

Legacy

Like Princess Charlotte Augusta before her and Princess Diana Spencer after her, the sudden and tragic death of Lady Mary FitzRoy in December 1847 was met with collective gloom and an outpouring of grief.[64] When news reached Annabella Boswell in Guruk (Port Macquarie) on Monday 20 December, she wrote in her diary:

This dreadful event has caused universal sorrow throughout the Colony. Lady Mary had travelled so much in the country and become personally acquainted with so many of its inhabitants that they feel as if a dear friend had been snatched away from them. All who had seen her, and all who had heard of her, unite in bewailing her sudden and melancholy end… for no one but a true Christian could have possessed the many virtues of this most kind and excellent lady.’[65]

In Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa (Wellington, New Zealand), James Coutts Crawford wrote in his diary of the accident, noting that ‘Lady Mary seems to have been most popular in the Colony from her kindly hospitable & plain unaffected manners.’[66] Finally, in January 1848 Eleanor Stephen, the wife of Sydney judge Sir Alfred Stephen, wrote to her daughter that ‘The mourning for poor Lady Mary is now laid aside, and her name will soon cease to be mentioned, yet her lamentable death stubbornly refuses to fade entirely from public memory.’[67] Indeed, Eleanor was correct, and the memory of Lady Mary did refuse to fade entirely from the memory of those in New South Wales. For years following her death there was debate as to where exactly the accident took place and ‘the exact position of the now historical tree against which Lady Fitzroy was thrown.’[68] There were also rumours that Lady Mary’s body had also been secretly exhumed and returned to England, as her family deemed it rather unsuitable that she had been interred next to a man who was not her husband.[69] There is, however, no historical evidence to prove this local legend.

In 1887 Mr. Hugh Taylor, a Member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly for Parramatta and Alderman of the Borough of Parramatta, headed a movement to commemorate Lady Mary by erecting the memorial at the site of her death. Taylor had reportedly met the governor’s wife as a youth and remembered her being ‘never happy unless she was doing good, getting the young around her, and gaining the love and affection of persons of every degree with whom she came in contact.’[70] On ‘Centenary Day’ 26 January 1888, large crowds gathered near what was then the four-year-old Tudor-style George Street Gatehouse entrance to Parramatta Park to witness the unveiling of the monument, next to the tree where the accident had supposedly occurred.[71]

Left: “Lady Fitzroy’s Monument, Parramatta Park,” Scenes of Parramatta Park, N.S.W., by Broadhurst, (c. 1900–1927), PXA 635 / 712-718 / FL1011362; Right: The Avenue of Oaks and FitzRoy memorial with the George Street ‘Tudor’ Gatehouse in the background. “A View at Parramatta Park,” Scenes of Parramatta Park, N.S.W., by Broadhurst, (c. 1900–1927), PXA 635 / 712-718 / FL1011360, State Library of New South Wales.

Similar scenes were again seen in February 2017, when a life-sized bronze statue of Lady Mary by Gillie and Marc was unveiled in Gympie in Queensland to celebrate the lady who inspired the names of several key locations in the area, such as the Mary River.[72] The lamentable and tragic death of Lady Mary FitzRoy not only cemented her place in the history of Parramatta and the Colony of New South Wales, but the collective and long-lasting mourning that occurred afterwards is telling of values and ideals that colonial Australians placed in their leading women during the first hundred years of its founding—industriousness, charity, and above all, compassion.

![Lady FitzRoy's unfinished quilt [detail]](https://parramattaburialground.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/lady-fitzroys-unfinished-quilt-detail.png)

CITE THIS

Sarah A. Bendall, “Lady Mary FitzRoy: The People’s Lady,” St. John’s Online, (2020), https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/lady-fitzroy/, accessed [insert current date]

Acknowledgements

Biographical selection, assignment, research assistance, editing & multimedia: Michaela Ann Cameron.

Author’s note: I would like to thank Professor Penny Russell and her Research Assistant Dr. Melissa Harper, as well as Dr. Michaela Ann Cameron for sharing sources compiled on the FitzRoys during their time in Cadi (Sydney). Special thanks to St. John’s Churchwarden, Mark Pearce, for his assistance in clarifying Sir Charles FitzRoy’s lineage.

References

Primary Sources

- Annabella Boswell, Annabella Boswell’s Journal: Australian Reminiscences Illustrated with Her Own Watercolours and Contemporary Drawings and Sketches, (North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1987).

- James Coutts Crawford, diary entry dated 7 December 1847 in “Diaries of J. C. Crawford, 1837–1865/File 4/Diary,” (AJCP ref: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-755361074), in Papers of James Coutts Crawford, 1837–1880 (as filmed by the AJCP), (AJCP Reel: M600, National Library of Australia. Filmed at the private residence of Brigadier H. N. Crawford, Fife, as part of the Australian Joint Copying Project, 1954, 1966 (AJCP Reels: M600, M687–M688). Original microfilm digitised as part of the NLA AJCP Online Delivery Project, 2017–2020.

- English School, Lady Mary FitzRoy and Lady Sophia Cecil, c.1820, sold by Bonhams, New Bond Street, London in 2007.

Secondary Sources

- Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2 (2001).

- Phillip Buckner, “FitzRoy, SIR CHARLES AUGUSTUS,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 8, (Toronto: University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fitzroy_charles_augustus_8E.html, accessed 4 March 2020.

- John Malcolm Bulloch, The Gordon Book, (London: Bazaar of the Fochabers Reading Room, 1902).

- Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006).

- Lorinda Cramer, “Making a Home in Gold-rush Victoria: Plain Sewing and the Genteel Woman,” Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 48, No. 2 (2017): 213–226, https://doi.org/10.1080/1031461X.2017.1293705, accessed 5 May 2020.

- Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016).

- Hilary Davidson, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen: Regency Fashion, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

- Annette M. Gero and Kim Mclean, The Fabric of Society: Australia’s Quilt Heritage from Convict Times to 1960, (Sydney, Beagle Press: 2008).

- The Goodwood Estate, Exhibitions: “Dancing Into Battle: The Duchess of Richmond’s Ball 15th June 1815,” Goodwood, (2015), https://www.goodwood.com/globalassets/venues/downloads/goodwood-dancing-into-battle.pdf, accessed 29 May 2020.

- F. Henderson and Roger T. Stearn, “Lennox, Charles, fourth duke of Richmond and fourth duke of Lennox (1764–1819), army officer,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-16452, accessed 3 March 2020

- Kennedy, “From the Ballroom to the Battlefield: British Women and Waterloo,” in A. Forrest, K. Hagemann, J. Rendall, (eds.), Soldiers, Citizens and Civilians. War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

- Elizabeth Longford, Wellington: The Years of the Sword, (New York: Smithmark, 1970).

- Cathy McHardy, “The Monument to Lady Fitzroy, Parramatta Park,” Parramatta Heritage Centre: Research Services, City of Parramatta Council, (2016), http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2016/12/22/the-monument-to-lady-fitzroy-parramatta-park/, accessed 20 March 2020.

- Louise Mitchell, “Introduction,” Labours of Love: Australian Quilts 1845–2015, (Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre, Sutherland Shire Council, 2015).

- National Trust of Australia (NSW), “Frederica Josephson and Lady Mary Fitzroy quilts from the National Trust Collection,” National Trust Australia, (2017), https://www.nationaltrust.org.au/frederica-josephson-and-lady-mary-fitzroy-quilts-from-the-national-trust-collection/, accessed 20 March 2020.

- Penny Russell, Savage or Civilised? Manners in Colonial Australia, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010).

- Anita Selzer, Governors’ Wives in Colonial Australia, (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2002).

- George F. G. Stanley, “LENNOX, CHARLES, 4th Duke of RICHMOND and LENNOX,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 5, (Toronto: University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lennox_charles_richmond_5E.html, accessed 4 March 2020.

- John M. Ward, “FitzRoy, Sir Charles Augustus (1796–1858),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1966, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fitzroy-sir-charles-augustus-2049/text2539, accessed online 4 March 2020.

NOTES

[1] Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016), pp. 17–18.

[2] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2 (2001), p. 234.

[3] Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016), p. 21.

[4] T. F. Henderson and Roger T. Stearn, “Lennox, Charles, fourth duke of Richmond and fourth duke of Lennox (1764–1819), army officer,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-16452, accessed 3 March 2020.

[5] Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016), p. 32.

[6] Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016), p. 39.

[7] Elizabeth Longford, Wellington: The Years of the Sword, (New York: Smithmark, 1970), p. 416.

[8] Elizabeth Longford, ‘194,’ in Max Hastings, (ed.), The Oxford Book of Military Anecdotes, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 232–4.

[9] C. Kennedy, “From the Ballroom to the Battlefield: British Women and Waterloo,” in A. Forrest, K. Hagemann, J. Rendall, (eds.), Soldiers, Citizens and Civilians. War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), p. 137.

[10] Cited in John Malcolm Bulloch, The Gordon Book, (London: Bazaar of the Fochabers Reading Room, 1902), p. 42.

[11] Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016), p. 76; T. F. Henderson and Roger T. Stearn, “Lennox, Charles, fourth duke of Richmond and fourth duke of Lennox (1764–1819), army officer,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-16452, accessed 3 March 2020; John Malcolm Bulloch, The Gordon Book, (London: Bazaar of the Fochabers Reading Room, 1902), p. 40.

[12] Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016), pp. 79–80.

[13] For a discussion about “Turtle Island,” the indigenous name for North America, see “Name-Calling: Notes on Terminology” in Michaela Ann Cameron, (Ph.D. Diss.), “Stealing the Turtle’s Voice: A Dual History of Western and Algonquian-Iroquoian Soundways from Creation to Re-creation,” (Sydney: University of Sydney, 2018), http://bit.ly/stealingturtle, accessed 13 April 2020. T. F. Henderson and Roger T. Stearn, “Lennox, Charles, fourth duke of Richmond and fourth duke of Lennox (1764–1819), army officer,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-16452, accessed 3 March 2020; Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016), p. 120.

[14] George F. G. Stanley, “LENNOX, CHARLES, 4th Duke of RICHMOND and LENNOX,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 5, (Toronto: University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lennox_charles_richmond_5E.html, accessed 4 March 2020,

[15] “Death of the Duke of Richmond (1816) from Hydrophobia,” Mercury and Weekly Courier, 6 August 1886, p. 4; Alice Marie Crossland, Wellington’s Dearest Georgy: The Life and Loves of Lady Georgiana Lennox, (London: Universe Press, 2016), p. 124.

[16] Annabella Boswell, Annabella Boswell’s Journal: Australian Reminiscences Illustrated with Her Own Watercolours and Contemporary Drawings and Sketches, (North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1987), pp. 15–16.

[17] English School, Lady Mary FitzRoy and Lady Sophia Cecil, c.1820, sold by Bonhams, New Bond Street, London in 2007.

[18] Many thanks to Hilary Davidson for helping me to identify the time period of the dress and hairstyle worn by Lady Mary in this portrait. See: Hilary Davidson, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen: Regency Fashion, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

[19] John M. Ward, “FitzRoy, Sir Charles Augustus (1796–1858),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1966, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fitzroy-sir-charles-augustus-2049/text2539, accessed online 4 March 2020. Charles Moseley, Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage: Clan Chiefs, Scottish Feudal Barons, 107th edition, (Stokesley: Burke’s Peerage & Gentry, 2003).

[20] Phillip Buckner, “FitzRoy, SIR CHARLES AUGUSTUS,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 8, (Toronto: University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fitzroy_charles_augustus_8E.html, accessed 4 March 2020.

[21] John M. Ward, “FitzRoy, Sir Charles Augustus (1796–1858),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1966, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fitzroy-sir-charles-augustus-2049/text2539, accessed online 4 March 2020.

[22] James Silk Buckingham, The Oriental Herald and Colonial Review, Vol. 1, (London: J.M. Richardson, 1824), p. 709; Great Britain House of Lords, Journals of the House of Lords, Vol. 60, (London: H.M. Stationary Office, 1828), p. 622.

[23] For the indigenous endonyms in the Canadian context and their translations, see “Name-Calling: Notes on Terminology,” in Michaela Ann Cameron, (Ph.D. Diss.), “Stealing the Turtle’s Voice: A Dual History of Western and Algonquian-Iroquoian Soundways from Creation to Re-creation,” (Sydney: University of Sydney, 2018), especially pp. 34–5, http://bit.ly/stealingturtle, accessed 13 April 2020. John M. Ward, “FitzRoy, Sir Charles Augustus (1796–1858),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1966, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fitzroy-sir-charles-augustus-2049/text2539, accessed online 4 March 2020.

[24] Annabella Boswell, Annabella Boswell’s Journal: Australian Reminiscences Illustrated with Her Own Watercolours and Contemporary Drawings and Sketches, (North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1987), p. 151. Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 156.

[25] West Sussex Record Office, Chichester/National Library of Australia, Canberra: Microfilm Reel M1549, Goodwood Mss 1653, fols. 573, 584, 611, https://www.nla.gov.au/sites/default/files/blogs/m_822_m1549-m1550_west_sussex_record_office.pdf, accessed 3 March 2020.

[26] “Arrival of His Excellency Sir Charles Augustus Fitzroy,” Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer (NSW : 1845 – 1860), Saturday 8 August 1846, p. 1.

[27] “ARRIVALS OF THE WEEK,” Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 – 1904), Saturday 5 September 1846, p. 4; “Arrival of His Excellency Sir Charles Augustus Fitzroy,” Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer (NSW : 1845 – 1860), Saturday 8 August 1846, p. 1 and “No title” Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer (NSW : 1845 – 1860), Saturday 8 August 1846, p. 2; “First Visit of His Excellency the Governor to Parramatta,” Hawkesbury Courier and Agricultural and General Advertiser (Windsor, NSW : 1844 – 1846), Thursday 20 August 1846, p. 4.

[28] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 234.

[29] “FIRST VISIT OF HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR TO PARRAMATTA,” Hawkesbury Courier and Agricultural and General Advertiser (Windsor, NSW : 1844 – 1846), Thursday 20 August 1846, p. 4.

[30] Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 153; Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 232.

[31] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 233; Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 153.

[32] Badger notes that ‘Word soon spread that entree to Government House depended less upon breeding or social standing and more upon whether or not the company was congenial to the Governor, his sons and his cousin Lieutenant-Colonel Godfrey Mundy. See: Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 232.

[33] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 234; Penny Russell, Savage or Civilised? Manners in Colonial Australia, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010), p. 126.

[34] Penny Russell, Savage or Civilised? Manners in Colonial Australia, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010), p 127.

[35] Penny Russell, Savage or Civilised? Manners in Colonial Australia, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010), p. 114, 122, 124–5.

[36] Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 155; Penny Russell, Savage or Civilised? Manners in Colonial Australia, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010), p. 114.

[37] Anita Selzer, Governors’ Wives in Colonial Australia, (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2002), pp. 8, 10.

[38] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 242; Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 154.

[39] Annabella Boswell, Annabella Boswell’s Journal: Australian Reminiscences Illustrated with Her Own Watercolours and Contemporary Drawings and Sketches, (North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1987), p. 161.

[40] “GOVERNMENT HOUSE BALL,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Monday 19 October 1846, p. 2.

[41] Penny Russell, Savage or Civilised? Manners in Colonial Australia, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010), pp. 128–9; Karina Wright, “A Very Sydney Scandal,” Sydney Living Museums, (5 June 2015), https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/2015/06/05/very-sydney-scandal, accessed 7 May 2020.

[42] Annabella Boswell, Annabella Boswell’s Journal: Australian Reminiscences Illustrated with Her Own Watercolours and Contemporary Drawings and Sketches, (North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1987), p. 151.

[43] Annabella Boswell, Annabella Boswell’s Journal: Australian Reminiscences Illustrated with Her Own Watercolours and Contemporary Drawings and Sketches, (North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1987), p. 151.

[44] Lorinda Cramer, “Making a Home in Gold-rush Victoria: Plain Sewing and the Genteel Woman,” Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 48, No. 2 (2017), pp. 213, 217; Louise Mitchell, “Introduction,” Labours of Love: Australian Quilts 1845–2015, (Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre, Sutherland Shire Council, 2015), p. 8.

[45] Annette M. Gero and Kim Mclean, The Fabric of Society: Australia’s Quilt Heritage from Convict Times to 1960, (Sydney, Beagle Press: 2008), p. 13.

[46] National Trust of Australia (NSW), “Frederica Josephson and Lady Mary Fitzroy quilts from the National Trust Collection,” National Trust Australia, (2017), https://www.nationaltrust.org.au/frederica-josephson-and-lady-mary-fitzroy-quilts-from-the-national-trust-collection/, accessed 20 March 2020; Louise Mitchell, “Introduction,” Labours of Love: Australian Quilts 1845–2015, (Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre, Sutherland Shire Council, 2015), p. 15.

[47] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 154.

[48] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 242.

[49] Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 153.

[50] “MOST MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT – DEATH OF LADY MARY RITZROY AND LIEUTENANT C. C. MASTERS, A.D.C.,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Wednesday 8 December 1847, p. 2.

[51] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 236.

[52] “MOST MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT – DEATH OF LADY MARY RITZROY AND LIEUTENANT C. C. MASTERS, A.D.C.,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Wednesday 8 December 1847, p. 2.

[53] “MOST MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT – DEATH OF LADY MARY RITZROY AND LIEUTENANT C. C. MASTERS, A.D.C.,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Wednesday 8 December 1847, p. 2.

[54] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 236.

[55] “MOST MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT – DEATH OF LADY MARY RITZROY AND LIEUTENANT C. C. MASTERS, A.D.C.,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Wednesday 8 December 1847, p. 2.

[56] “MOST MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT – DEATH OF LADY MARY RITZROY AND LIEUTENANT C. C. MASTERS, A.D.C.,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Wednesday 8 December 1847, p. 2.;

[57] Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 155.

[58] Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 155; “MOST MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT – DEATH OF LADY MARY RITZROY AND LIEUTENANT C. C. MASTERS, A.D.C.,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Wednesday 8 December 1847, p. 2.

[59] Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), pp. 236-7.

[60] Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy, (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), p. 155; Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 237.

[61] “FUNERAL OF LADY MARY FITZROY AND LIEUT. C. C. MASTER,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Friday 10 December 1847, p. 2.

[62] “Friday, December 10, 1847,” The Australian (NSW : 1824 – 1848), Friday 10 December 1847, p. 3.

[63] “FUNERAL OF LADY MARY FITZROY AND LIEUT. C. C. MASTER,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Friday 10 December 1847, p. 2.

[64] Princess Charlotte was the only child of George IV who died in childbirth in 1817, provoking an outpouring of grief and anxiety about the question of succession. It is her untimely death that paved the way for Victoria, her cousin, to inherit the British throne. A. S. Badger has noted, The Sydney Morning Herald likened the outpouring of grief for Lady Mary to that of Princess Charlotte. Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 237.

[65] Annabella Boswell, Annabella Boswell’s Journal: Australian Reminiscences Illustrated with Her Own Watercolours and Contemporary Drawings and Sketches, (North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1987), p. 183.

[66] James Coutts Crawford, diary entry dated ?? December 1847 in “Diaries of J. C. Crawford, 1837–1865/File 4/Diary,” (AJCP ref: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-755361074), in Papers of James Coutts Crawford, 1837–1880 (as filmed by the AJCP), (AJCP Reel: M600, National Library of Australia. Filmed at the private residence of Brigadier H. N. Crawford, Fife, as part of the Australian Joint Copying Project, 1954, 1966 (AJCP Reels: M600, M687–M688). Original microfilm digitised as part of the NLA AJCP Online Delivery Project, 2017–2020.

[67] Cited in Jim Badger, “The Lamentable Death of Lady Mary FitzRoy,” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 87, No. 2, (2001), p. 240.

[68] “Death of Lady Mary Fitzroy,” The Kiama Independent, and Shoalhaven Advertiser (NSW : 1863 – 1947), Friday 28 October 1887, p. 2.

[69] Judith Dunn, The Parramatta Cemeteries: St. John’s, (Parramatta, NSW: Parramatta and District Historical Society, 1991), pp. 24–5.

[70] “THE PROCESSION,” The Cumberland Mercury (Parramatta, NSW : 1875 – 1895), Saturday 28 January 1888, p. 5.

[71] Cathy McHardy, “The Monument to Lady Fitzroy, Parramatta Park,” Parramatta Heritage Centre: Research Services, City of Parramatta Council, (2016), http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2016/12/22/the-monument-to-lady-fitzroy-parramatta-park/, accessed 20 March 2020.

[72] When Governor Charles FitzRoy visited Queensland after Mary’s death he reportedly named many locations after her, such as the Mary River and Maryborough. Megan Kinninment, “Statue unveiled in Gympie is legacy of tragic historic figure Lady Mary Fitzroy,” ABC News Online, (14 February 2017), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-14/statue-unveiled-in-gympie-is-legacy-of-tragic-historic-figure/8268986, accessed 20 March 2020.

© Copyright 2020 Sarah A. Bendall and Michaela Ann Cameron for St. John’s Online