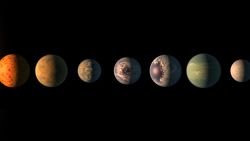

Since the first exoplanets were discovered in the 1990s, many have wondered if we might find another Earth out there, a place called Planet B.

Natalie Batalha, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, has watched the field of exoplanet science grow and change since those initial discoveries. Batalha served as the co-investigator and mission scientist on the Kepler mission. Kepler was the first mission capable of searching for Earth-size planets around other stars and it transformed exoplanet science.

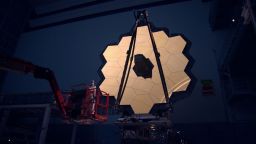

“The first decade of exoplanets was postage stamp collecting, where you discover a planet one at a time,” she said. “But then Kepler launched and broke open a bottleneck in terms of sensitivity. We were discovering planets hundreds at a time. (The James Webb Telescope) will give us this new lens on studying exoplanet diversity. We’re entering this third epoch of exoplanet atmosphere characterization.”

So far, the study of exoplanets hasn’t revealed another Earth, and it’s unlikely even with the upcoming launch of the James Webb Space Telescope in December. The observatory will look inside the atmospheres of exoplanets orbiting much smaller stars than our sun.

“One of the key aspects of Webb is to understand whether they indeed have at least some of the properties of habitability, but it won’t be won’t be a true Earth analog,” said Klaus Pontoppidan, Webb project scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

But the planets it will study could be connected with an intriguing idea: What if life happens differently outside of Earth? And it’s something that the successors of this telescope could investigate in the decades to come.

“There really is no Planet B for us,” said Jill Tarter, astronomer and former director of the Center for SETI Research who currently holds the Chair Emeritus for SETI Research. “Unless we figure out a way to solve all of the global issues that we face here and mitigate those challenges, wherever we go we’ll create the same problems that we’ve done here on this planet. There’s no escape hatch.”

What is Planet B?

If there is a Planet B somewhere out there, is it more like Earth, or will it surprise us and be something completely unexpected?

“When we find a Planet B, I want it to be a true Earth twin, a planet orbiting a sun-like star and the Earth-like orbit that has a thin atmosphere and oceans and continents,” said Sara Seager, astrophysicist, planetary scientist and professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

As astronomers have been keen to point out, every telescope has brought a wealth of unexpected discoveries in addition to the things they were planning to observe. Planet B could be similar.

“I kind of really want us to be able to find life on something that looks not a lot like Earth,” said Nikole Lewis, astrophysicist and an assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell University.

“It’s safe for us to say if it looks like Earth and it smells like Earth, then it’s probably Earth and therefore has life. That’s not adventuresome enough for me, so I would love to kick it out there and really start to look at the atmospheric chemistry and temperature of planets that are maybe a little bit bigger than Earth,” she said.

The search for Planet B isn’t black and white: It’s incredibly complicated, balancing what we understand about the process of life on Earth with what we don’t know.

On Earth, even in its most extreme environments, life is carbon-based, liquid water has its part to play as a solvent for biochemistry, and DNA encodes genetic information, Batalha said. It stands to reason that life elsewhere is likely carbon-based and relies on water. And hydrogen, oxygen and carbon are very abundant elements in the universe.

“Planet B, based on how we’re looking, is a planet with surface liquid water,” Batalha said. “Besides looking for biosignatures, I think what Webb might do better is look for signs of a habitable environment.”

It’s also possible that if the conditions aren’t just right in other places, life may find a way to “exist in niches and maybe even find other biochemical pathways when hard pressed,” she said.

Perhaps life on another planet may use methanol rather than water for biochemistry or we’ll develop different metrics and signatures for detecting habitable planets and life on them in the future, she said.

The key factor the astronomers we spoke with agreed on was keeping an open mind in the search for life – and a reminder to respect what we find.

“If there is a Planet B, by definition, it’s not our planet,” Batalha said. “We talk about this idea of looking for a habitable worlds as if they’re ours for the taking. And if a planet is exactly like Earth with the conditions for life, then by definition, it’s a living world, and it’s not ours.”

Identifying a sign of life

Webb won’t likely be the key tool in identifying signs of life on another planet. That task is for future telescopes, like the one outlined in the recently released Astro2020 decadal survey that will look at 25 potentially habitable exoplanets.

“We know how to find that planet, but it’s put off until 2045 or later,” Seager said.

Life, as we understand it, needs energy, liquid and the right temperature, she said. What happens when a potential sign of life is detected? Finding the sign is fantastic – figuring out the next step is crucial, Seager said.

If it’s determined that there was no other way a potential sign of life could be created, collaboration will be a key aspect, Lewis said. Engaging with chemists, biologists and people of different disciplines outside of astronomy and planetary science can determine the path forward.

“My hope is that we’ll be careful, and that we will engage with all of the relevant experts to try to understand if this is in fact, a signature that could only mean that life is on this planet, and then hopefully announced such a thing to the public,” Lewis said.

And it likely won’t be a singular moment that occurs overnight, Batalha said.

“It’s going to play out over a very long time as we continue to study the biochemistry of the world because any biosignature that we can come up with, you have to demonstrate that there is not another abiotic (physical, rather than biological) way of producing that signal. That’s going to take a long time.”

The search for life is a journey that will involve taking new pathways, asking new questions and developing new hypotheses. Then, experiments will be devised to help answer those questions.

Batalha hopes that future telescopes can help scientists complete the planetary census, including how frequently Eartth-like planets occur in the galaxy.

“I think the most important thing is that we just keep it going and keep moving forward,” Batalha said.

Understanding the significance of what observations and scientific results mean in the search for life is a priority for NASA, as identified in a recent report. Led by Jim Green, NASA’s chief scientist, the paper encourages the establishment of a new scale to evaluate evidence that answers the question of if we’re truly alone.

“Having a scale like this will help us understand where we are in terms of the search for life in particular locations, and in terms of the capabilities of missions and technologies that help us in that quest,” Green said in a statement.

The seven levels of the scale reflect a staircase of steps on the way to proclaiming a positive result in the search for life beyond Earth.

“Until now, we have set the public up to think there are only two options: it’s life or it’s not life,” said Mary Voytek, head of NASA’s Astrobiology Program, in a statement. “We need a better way to share the excitement of our discoveries, and demonstrate how each discovery builds on the next, so that we can bring the public and other scientists along on the journey.”

The enduring search for life

Tarter believes that the answer to finding life may rely on technosignatures, rather than biosignatures, because the evidence of past or present technology is “potentially a lot less ambiguous.”

Biosignatures could be gases or molecules that show signs of life. Technosignatures are signals that could be created by intelligent life.

They are “something that we can observe to indicate that not only is there life on a distant planet, but that it’s logically competent and has built or created something that we can observe with our ever-improving capabilities for looking at the universe,” she said.

Since the 1960s, scientists have been listening for radio signals or searching for optical light wavelengths that indicate that someone out there is transmitting something.

If an intelligent civilization “modified their environment, such as building solar collectors to gather a lot of energy and repurpose it for use on a planetary surface, it’s possible that we might be able to observe the consequences of that technology utilization,” Tarter said.

Tarter is encouraged by the investment in missions investigating the search for past and current life In our own solar system, like the many missions exploring Mars, Dragonfly that will explore Saturn’s moon Titan and Europa Clipper that will fly through plumes of ocean material at Jupiter’s moon.

In the future, she hopes for missions that will dig even deeper into planets than the Perseverance rover, which is collecting samples from rocks on Mars. Exploring deeper than 32.8 feet (10 meters) could show evidence of ancient technology.

“I think within a century will have done a pretty good job exploring for life, but I really like to keep an open mind,” Tarter said.

If the samples collected by Perseverance, which will be returned to Earth by future missions in the 2030s, show evidence of ancient biological life on Mars, it begs another question.

“Are we Martians? Early in the solar system, there was a lot of exchange of material, collisions were abundant and pieces of rock that chipped off Mars ended up landing on Earth,” Tarter said. “It’s possible that life started somewhere other than Earth.”

An even more exciting possibility is the example of a second genesis if the biology on Mars it not related to us, but an independent origin of life, Tarter said. “That would mean it happened twice, and it’s ubiquitous anywhere. It’s astonishing. I hope I live to see it.”