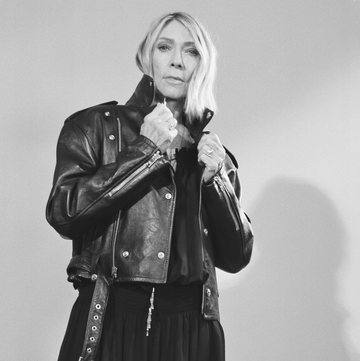

Yves Saint Laurent dubbed her the girl of the '70s, and she was a favorite of countless famed photographers, including Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Jeanloup Sieff, Hiro, David Bailey, and Helmut Newton. But Marisa Berenson, the iconic model, actress, and society darling, very nearly didn't make it in front of their cameras at all. At the age of 16, just as the world was tiptoeing into the radical '60s, modeling maven Eileen Ford took one look at the lanky, doe-eyed, snub-nosed teenager—so different from the high-cheekboned, haughty whippets who reigned over the pages of fashion magazines in the '50s—and decreed, "You'll never make a model."

"I came home devastated," says Berenson with the aristocratic lilt and dramatic elocution that fueled her star turn in 2009's I Am Love. After all, looks notwithstanding, modeling was practically her birthright: Her christening portrait, shot by Penn for Vogue, showed proud grandmother Elsa Schiaparelli, sternly surveying over the bassinet, next to Berenson's mother, who was known by the kicky nickname Gogo rather than her cumbersome title, Countess Maria Luisa Yvonne Radha de Wendt de Kerlor. Berenson posed for Avedon as a winsome little girl and for Bailey in London at 15. But she had her sights set higher than simply It girldom: "I wanted to become a model since I was a kid."

Luckily, Berenson encountered family friend Diana Vreeland at a ball in New York City on the arm of her father, Onassis shipping executive turned diplomat Robert Berenson. "We must photograph you," the legendary fashion editor exclaimed, seeing the possibility in her miles of tanned limbs, carefree smile, and wide eyes that could express anything from innocent girlishness to joyful extroversion. Berenson was immediately set up to shoot with Bert Stern and then packed off to Paris for the fashion shows with Bailey. "That's how it all started. It's thanks to her that I had a career," says Berenson, who at 64 can still rock a look on a runway, as she did for Tom Ford's Spring 2011 collection. Her five decades of work is on display in a new book, Marisa Berenson: A Life in Pictures.

Soon, Berenson was everywhere, and her photos helped define a generation—from her youthquaking miniskirt days to her exotic, golden-skinned glamour. The only person who might have been happier had Berenson not modeled and instead remained the jeune fille bien élevée she was meant to be was Schiaparelli. Despite her love of shocking the bourgeoisie with dramatic surrealist gestures like cellophane capes and lobster dresses, the designer remained a traditionalist at heart. "She was furious at Diana," Berenson remembers. "She didn't want me to be in fashion at all. She wanted me to get married into a very good family and just live a life that was the contrary of what she did."

But Vreeland was devoted to her new discovery. "She was like my godmother. She was the one who took me under her wing," says Berenson, who dined with Diana and her husband, Reed, at least once a week. (Vreeland dubbed Berenson and her equally gorgeous photographer sister, Berry, the Mauretania and the Berengaria, after the two ships.) "Diana used to send memos around saying, 'Marisa's neck has grown two inches this year. I want you to emphasize her neck.' Or 'Her skull is the most beautiful thing I've ever seen. I want you to pull her hair back and photograph her head.'" At this, Berenson breaks into peals of unrestrained laughter.

Her disapproving grandmother should have breathed a sigh of relief that her great friend Salvador Dalí didn't get his hands on Berenson first. "We went to visit him in Spain when I was only 13, and he wanted to paint me in the nude," Berenson recounts. "He said I had 'hip bones like cherry-stones.' Can you imagine? Whatever that means. My mother was outraged. 'He's just a dirty old man,' she said. And of course I regret it because I would give anything to have a nude by Dalí." The two remained close, and Berenson would visit him at his New York quarters at the St. Regis Hotel. "One day, I went to have tea with him, and he had all of these wild ocelots climbing all over the furniture. He said, 'One is pregnant, and I'll give you a kitten if you want,'" she says, laughing. "I said, 'No, thank you.' My apartment was so small, and I could just imagine them tearing my walls apart!"

By then, Berenson was the toast of two continents, representing as she did both the Old World and the new swinging spirit. "She's a seismograph, registering the latest tremors in the current of the moment— the newest trends, places to go, ways to look," Bazaar said. Berenson didn't hesitate to model Halston standing on top of Iran's Blue Mosque for Henry Clarke or pose nude save for gold necklaces for Penn. "I was very free," she says, remembering how her transparent dresses shocked the family of one of her many suitors, David de Rothschild. "It was my form of expression. I didn't think twice about it; it didn't faze me to show my breasts. Maybe my grandmother wasn't happy about it, and neither was Marie-Héléne de Rothschild, but I didn't care." The laugh bubbles up again. "It was fun."

And fun is definitely what she was having. In 1968, already one of the highest-paid models in the industry, she befriended Diane von Furstenberg (then Diane Halfin and working as an assistant to a photo agent in Paris). "One day I said to her, 'Come with me to Capri.' And she said, 'I don't have any money,' so I pulled out this wad of money from my bag and just gave it to her." The two became inseparable on the international scene, jetting from party to party. "We used to check into the Palace Hotel in St. Moritz or the Quisisana in Capri and have such a ball," she says. But they were still girls at heart: "We used to iron our hair on an ironing board before going out at night because she and I had the same kind of curly hair."

"We would swim in Sardinia with so many jewels, it was amazing that we did not sink. We would wear bracelets from our wrists to our elbows," von Furstenberg remembers. "In Paris, we used to hang out together on the weekends and see three movies in a row, and then we would go to La Coupole for dinner. We had so many great laughs."

Berenson was also a regular guest at the storied balls that were the social highlights of the time, from Truman Capote's 1966 Black and White Ball (where she dressed as an Oriental princess after Halston mistakenly gave her original costume to Candice Bergen) to Marie-Héléne de Rothschild's 1971 Bal Proust at the family's opulent Château de Ferrières. While even the Duchess of Windsor stuck closely to the theme, wearing a purple feather in her hair, Berenson went as Marchesa Luisa Casati—the idea of costume designer Piero Tosi, with whom Berenson had just worked on the film Death in Venice. "You are not going to go like all those other women," he proclaimed, instead dressing her in a Paul Poiret dress adorned with jeweled snakes, a curled red wig, black lipstick, and a black tiara. "When I walked in, nobody recognized me," she says. "I had so much fun because I was totally sticking out from everybody else.

"It was a different time," Berenson says with a sigh, pointing out that for all the "extraordinary people" at the Bal Proust, the only photographer present was Cecil Beaton, unlike the legions of paparazzi today. "Nobody has those places anymore, first of all, and the ones that do lay very, very low because the world is not at all what it used to be, and you don't show off. ... I don't know if there's so much individuality anymore," she continues, dismissing today's young social set. "I think there are very few people who have a real style, a real personality, and real beauty. Everything sort of melts into everything else."

By the time she was embodying the Marchesa Casati, Berenson had made waves in Hollywood and was soon starring in Bob Fosse's Oscar-winning film Cabaret and Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon. It's hardly surprising that Andy Warhol was also captivated by Berenson's energy and her pedigree, and she spent hours at the Factory sitting for Warhol's camera. "He was in awe of a certain kind of world," she says. "He loved the fact that he had become so successful and all these grand social ladies would pay a fortune to have their portraits done by him." The two went to the Venice Film Festival together, and when Berenson finally decided to settle down with the dashing James Randall in 1976, Warhol came to Beverly Hills to watch the wedding preparations for the 800-person fete, with guests from Jack Nicholson and Anjelica Huston to best man George Hamilton. "It was like Andy's favorite part was the preparation," she says. "I was redecorating the house, and all the furniture was coming in, and the orchids, and he photographed all of that. The day of the wedding, I was in the bathroom with my rollers on and Valentino was ironing my dress, and it was all so amusing for him," she says. "We were very close, Andy and I, but he was a strange person. You didn't always know what was going on inside his head."

Soon after, the marriage fell apart, although not before the birth of her daughter, Starlite Randall. It was one of many things that Berenson overcame with the spirituality she gained studying with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in the late '60s (alongside the Beatles and Mia Farrow, no less). Another was the more recent and tragic death of her beloved sister, Berry, on 9/11. "That plane going into that building is a constant image that you see all the time, and that's hard, because you can never have closure," she says. "It's always the questioning of what happened: Did she know? Did she not know? Did she suffer? Did she not? I try to take something really sinister and dark and turn it into something spiritual and full of light. That's the only way I could possibly survive—that and the belief that there's a life after and that I can communicate with her."

Then again, Berenson isn't one to dwell. She's always looking forward, to the next film, the next project, the next picture. "I'm not someone who lives in the past; I find other people live in my past," she says, brightening as that laugh returns. "I live in the present and the future."