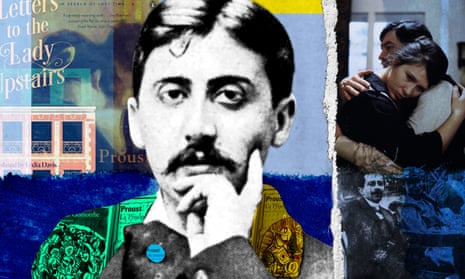

The long revered French novelist, critic and essayist is still thought to be one of the most influential authors of all time a century after this death on 18 November 1922. While Proust does have more than one work of fiction to his name - in 1896 he published the short story collection Les Plaisirs et Les Jours (Pleasures and Days), for example, and between 1895 and 1899 he wrote the autobiographical novel Jean Santeuil – when people refer to Proust they tend to be talking about A la Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time). Perhaps you’ve dipped in to one of the monumental novel’s seven volumes, or maybe you’ve struggled to find a way in; either way, literary translator Lucy Raitz has put together this handy guide to the great writer for anyone who wants to know his work better.

The starting point

The older narrator, who has forgotten everything about his childhood except the trauma of his mother failing to give him a goodnight kiss, dips a shell-shaped Madeleine in a cup of limeflower tea. Slowly the past uncurls its petals and Combray – the scene of all the family’s Easter holidays, with its walks, its river, its shops and its church – is restored to him. The place and its people are so vivid; unsurprisingly, since Combray is modelled on the little town of Illiers, not far from Chartres, where Proust’s father grew up and where Marcel did indeed spend holidays, staying with his aunt and uncle. Combray, which gives its name to the first part of the first volume, is the kind of place you might never want to leave, so if you stop there, you’re still winning.

The one to read on the beach

The second volume has the most beautiful and really untranslatable title A l’Ombre des Jeunes Filles en Fleurs. “In the shade of the girls in bloom” doesn’t sound quite the same – I think translator Scott Moncrieff did it better with Within a Budding Grove. This volume takes place in the fashionable fictional seaside resort of Balbec. The narrator, now a young man, is staying with his grandmother at the Grand Hotel. He meets the painter Elstir and a gang of sporty girls, with whom he falls collectively in love. It evokes summer scenes painted by the impressionists and, indeed, Elstir is modelled in part on Monet. The very best place to read this book would of course be the Normandy coast, where you could look up from the pages to see a view that really hasn’t changed since Proust himself stayed in the Grand Hotel in Cabourg more than 100 years ago.

If you like a mystery

In volume six, La Prisonnière (The Captive), one of the flowering girls, Albertine, has become the focus for the narrator’s passion, a passion founded in possessive jealousy, hence the title. He keeps Albertine – we don’t really know how – a virtual prisoner in the Paris apartment he shares with his parents and housekeeper, Françoise. Since we see things entirely from his point of view, Albertine remains a shadowy figure, which has prompted other writers to intervene. Like Jean Rhys telling the first Mrs Rochester’s story via Wide Sargasso Sea, the writer Jacqueline Rose has told Albertine’s, and she is not the only one; the director Chantal Akerman has done it too, in her film The Captive. Proust’s biographers agree that Albertine was modelled on Alfred Agostinelli, the writer’s chauffeur-secretary-lover, who died when he crashed his plane. Albertine too dies, shortly after escaping from the narrator, in a riding accident. Through the narrator’s grief and posthumous obsessive search to discover who Albertine really was, Proust exorcises his own remorse. Death haunts this volume, as Bergotte, the fictional writer, keels over in front of Vermeer’s View of Delft, lamenting his failure to equal the painter’s liveliness. Although the death itself is bathetic, its aftermath is majestic, and perhaps what Proust would have wished for himself:

They buried him, but all through the night of his funeral, in the lit shop-windows, his books, in groups of three, kept watch like angels with outstretched wings, and seemed, for him who was no longer there, the symbol of his resurrection.

The one to give a miss

Ideally, you wouldn’t skip any of them, but … in volume four, The Guermantes Way (Part Two) a staggering number of pages are devoted to one evening at the Duchesse de Guermantes’s house in the Faubourg St Germain in Paris. In The Songlines, Bruce Chatwin has a character called Rolf, who does nothing but read, making his way through the Duchesse de Guermantes’ “interminable” dinner party. It’s tempting to miss a course or two.

If you only read one

Easy. It has to be Un Amour de Swann (Swann in Love) which is that terribly 21st-century thing, a prequel. Swann’s Way is part two of the first volume, following Combray. In it, the narrator steps aside from his own consciousness to tell in every beautiful, terrible detail the story whose bare bones he has gleaned from his parents’, and grandparents’, conversations, that of Swann’s love affair with the unsuitable and unworthy Odette de Crécy. As a study in the miseries of unrequited love and obsessive jealousy, it is unparalleled. It also scotches any theory that Proust’s women are all men (often his ex-lovers) in disguise. Unlike Albertine, Odette is a woman with a complex and believable psyche. Swann in love also contains such gems as the hilariously ghastly characters the Verdurins, the piano sonata whose little phrase entrances Swann, yielding extraordinary musings on the power of music and wonderful descriptions of belle epoque Paris. It’s a bit too long to be termed a novella, but it feels like one, and might stand on the same shelf as Turgenev’s First Love, Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes or JL Carr’s A Month in the Country.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion