A hundred years ago, Lytton Strachey published Eminent Victorians, a sequence of four biographical essays whose elegance belied their punkish intent. Strachey’s subjects, although “targets” might be more accurate, were Florence Nightingale, General Gordon, Thomas Arnold and Cardinal Manning. These four eminences – the founder of modern nursing, the British empire’s most honoured military man, the reforming headmaster of Rugby School and Protestant England’s most prominent Catholic churchman – were simultaneously knocked down, duffed up and left looking slightly ridiculous. With language sharpened to a scalpel, Strachey cut away the fatty layers of celebratory bluster to reveal these heroes of Victorian Britain as deluded narcissists whose achievements depended on the ruthless exploitation of those around them. Gordon drank, “was particularly fond of boys” and slapped his servants; Manning had gone over to Rome from the C of E because it offered better job prospects; Nightingale was a psychotic bully who ran her saintly helpers ragged; while Arnold, in a wonderfully allegorical description, had legs that were slightly too short for his body. And all of them knew for a fact that God was on their side.

Biography, for good and for ill, would never be quite the same again. Over the previous 100 years, roughly the span of the 19th century, biography valued reticence over revelation. Prominent men (and the very occasional woman) were memorialised on paper in much the same way as they were materialised in stone. While every market town and London square had a giant statue of Nelson or Gladstone caught at their most flattering angle, every bookshelf sagged under the weight of a two-volume life that conveyed the most admirable aspects of its subject’s public career and stayed silent on the rest. These lacunae included but were not limited to homosexuality, bankruptcy, illegitimacy, alcoholism and telling whopping fibs. The Great, it went without saying, were also always Good.

From the first page of Eminent Victorians it is clear that something is up. The tyro author – Strachey’s only previous book had been a volume of academic criticism – proclaims that the old ways of writing about past lives will no longer do. “Our fathers and grandfathers have poured forth and accumulated so vast a quantity of information,” he explains, that any 20th-century historian or biographer would struggle to find patterns, make connections or even come up with a serviceable summary. What was needed instead was a “subtler strategy”. The biographer “will attack his subject in unexpected places; he will fall upon the flank, or the rear; he will shoot a sudden, revealing searchlight into obscure recesses, hitherto undivined”. Such pre-meditated violence could not be more different than the approach of the previous generation in which the biographer resembled nothing so much as a loyal family retainer, one who knew all his master’s funny little foibles but would rather die than expose them to the world’s impertinent gaze.

In that same two-page preface Strachey also airily dismisses the old biographical habit of throwing in everything in the hope that some of it would stick. In fact, he suggests, all it really does is bore people silly with its “ill-digested masses of material”, “slipshod style”, “tone of tedious panegyric”, “lamentable lack of selection, of detachment, of design”. What was needed instead was a “becoming brevity – a brevity which excludes everything that is redundant and nothing that is significant – that, surely, is the first duty of the biographer”.

What Strachey is talking about here is “significant form”, the guiding principle of literary modernism that was so important to his Bloomsbury peers Virginia Woolf and EM Forster. How something was written mattered just as much, maybe more, than the information it conveyed. Biography, like a painting or a novel, should be regarded not as objective but autonomous, a work of art with its own logical coherence and only a glancing relation to what lay beyond its frame. And it has turned out to be a thrilling legacy. For what is Alexander Masters’s brilliant trilogy of forgotten lives, starting with Stuart: A Life Backwards (2005), but an exploration of and challenge to biographical – for which read biological – form? Even those modern biographers who work within the cradle-to-grave tradition have been liberated by Strachey’s suggestion that what one leaves out is just as important as what goes in. No longer is it expected or even desirable to include chapter and verse on what the biographical subject had for breakfast or where their great-grandparents came from. Hilary Spurling’s exemplary two‑volume Matisse or Robert Caro’s multi-decker masterwork on Lyndon Johnson may be tethered firmly to the archive, but in voice and form they soar far above the clunky chronological dirge that used to pass as the only way of getting a life down on paper.

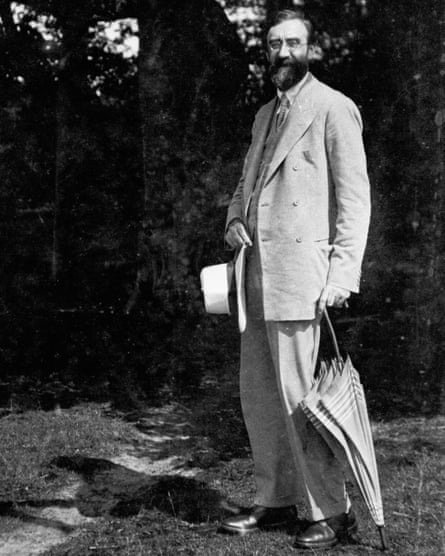

It’s no coincidence that Strachey’s radical new proposal about how to write the lives of others appeared in the closing months of the first world war. Yet what Strachey didn’t acknowledge, but we surely must, is the mixture of desire, envy and Oedipal rage that is in play every time a biographer picks their subject. When he unleashed his silky contempt on high-minded and ostensibly public spirited Victorians he was, in a sense, attacking his own family. He had been born in 1880 to a highly distinguished clan of colonial administrators and soldiers and it is hardly an accident that two of the eminences he set about cutting down to size, Nightingale and Gordon, were likewise leading figures of the great imperial enterprise. Nightingale dedicated her post-Crimean life to the health of the British army in India while Gordon was the governor general of the Sudan. In addition Strachey had endured a miserable time at boarding school. Here, perhaps, are the origins of his particular loathing of Arnold, who, thanks to the boosterism of the novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857), was now regarded as the man who had set the blueprint for what a proper young Englishman should be: pious, sporty, manly and not especially clever. For Strachey, who was gay, wheezy, atheist and a member of the intellectually elite Cambridge Apostles, it was hard to think of a less appetising model.

By marking the end of biographical deference Eminent Victorians bestowed an exhilarating freedom on the entire form. From now on life writers felt able to include the dark as well as the light. Sexual scandals, financial disgrace and general moral turpitude would be admitted to the public record rather than being left to languish in the margins as insider gossip and smirking innuendo. And yet, it sometimes seems as if this permission to be candid has degraded into a requirement to be rude. These days, unless a biography can boast a revelation, preferably of a sexual nature, then there is a feeling of flatness, as if the book has no particular reason to exist. And if, in the course of research, a biographer does happen to unearth something scandalous, then there’s a high risk that it will come to dominate the reviews, blotting out quieter but nonetheless crucial material. It happened 9 years ago when the coverage of John Carey’s judicious and scholarly biography of William Golding was dominated by news stories that trumpeted Carey’s discovery that, as an Oxford undergraduate, Golding had attempted to rape his 15 year old girlfriend. In the process Carey’s masterly analysis of Lord of the Flies, The Spire and Darkness Visible got temporarily drowned out.

There are other ways too in which Eminent Victorians, for all its sizzle and spice, set up potentially damaging precedents. Strachey did not believe in research, at least not the kind that biographers and historians do. Instead of looking at primary sources, spending dusty hours sorting through diary entries about bad plumbing (Nightingale) or The Real Presence (Manning) he culled what he needed from extant biographies and histories. Indeed, when working on his Manning chapter Strachey ordered so many books on the history of religion that his landlady assumed he must be studying for the church. Likewise Strachey’s essay on Nightingale draws mostly on the two-decker biography by Sir Edward Cook (1913), a book that Strachey himself had once considered writing but rejected on the grounds that Miss Nightingale “was a terrible woman”. How much more fun to cherry-pick information from Cook’s foot-slogging effort and work it up into a sprightly, “cynical” (Strachey’s word) takedown of the Lady with the Lamp.

As Strachey triumphantly demonstrates, there is nothing wrong with being the second or 20th person to come to a particular biographical subject. Released from the requirement to tell a now familiar story from scratch, you are left free to write the book you actually want. This principle is on spectacular display in Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage, his 1997 tour de force on DH Lawrence. Instead of adding to the heap of biographical and literary studies already in existence, Dyer produced an idiosyncratic account of his experience of failing to write the seminal work on his long-time literary hero. Just like Strachey, Dyer steered clear of dusty archives, limiting himself to the kind of printed sources that can be read in bed or packed into a suitcase.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion