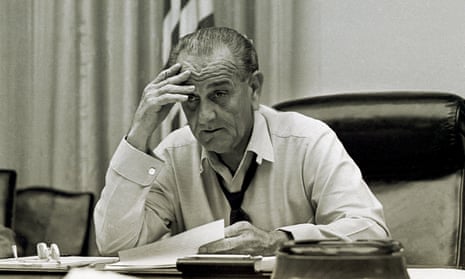

I wish I had a normal hero from history. Maybe Frederick Douglass, or Rosa Parks, or the person who set the video of Richard Spencer getting punched to the tune of Never Gonna Give You Up. But I don’t. I have an irrational fascination with Lyndon B Johnson, the 36th president of the United States. He is my ultimate problematic fave: obnoxious, crude, responsible for the escalation of the Vietnam war and the death of thousands of innocent civilians – and yet also the architect of so much of the modern (now crumbling) American welfare state. Johnson died 45 years ago today, and it’s hard to know what reaction is appropriate – commemoration, condemnation, or something in between.

The first thing to appreciate about LBJ’s presidency is the sheer amount of stuff that happened during it. From the fallout of JF Kennedy’s assassination to the passage of the Civil Rights Act to Vietnam, the subsequent protests and the Watts riots in LA – it was like the news fell asleep during the 1950s and was trying to make up for lost time. As a result, Johnson’s legacy is hazy: is he the patronising face of white America stopping progress in the civil rights movement? Is he a warmonger desperate for American dominance around the world? Is he the man who killed Kennedy with the help of the CIA because he didn’t like how JFK and Bobby made fun of his accent as vice-president (an upsettingly genuine conspiracy theory)?

Johnson can be portrayed as an accident – the rootin’ tootin’ southerner who fell into the presidency at the worst possible time, was in office during the disastrous war in Vietnam and resigned to let in the most corrupt president of all time (pre-2017, at least). This narrative can be tempting, but it ignores the fact that Johnson had been planning for this job his entire life. LBJ had been a congressman, a senator, a Senate minority and majority leader and vice-president before ascending to the presidency, and he transformed the scope of the federal government, pushing through social security acts that created Medicare and Medicaid, the first civil rights acts since reconstruction, the 1965 Voting Rights Act that tackled racial discrimination in southern polling centres, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, and the Higher Education Act of 1965.

These are not forgotten, discarded relics. Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start and the Food Stamp Act – all fundamental parts of LBJ’s Great Society legislation - serve tens of millions of eligible Americans to this day. The modern Republican party – or at least the part that is southern-facing, anti-big government and obsessed with “law and order” – was born as a direct response to LBJ’s own expansive and moralistic attitude towards the presidency: that the immense power of the country could be used to improve the lot of the poor.

Having said all that, it’s impossible to get away from the fact that Lyndon B Johnson was also a truly awful man. Anyone who nicknames his penis Jumbo and whirls it around whenever he’s in the john, shouting “Woo-eee, have you ever seen anything as big as this”, should probably be disqualified from any great man of history awards. In Joseph Califano’s brilliant The Triumph & Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson, the president spends a distressing amount of the book naked. If Johnson were president today, the sheer number of sexual assault allegations against him would be so high that he would have no choice but to … actually, no, that’s a bad example. Let’s say that if he were playing a president in a Netflix series, he would be quietly written out and replaced by Robin Wright.

Johnson was also famously crude: his line about difficult politicians – that it’s better to have them inside the tent pissing out than outside pissing in – isn’t even close to the worst thing he said. That award goes to the extremely graphic description he gave of the mating season of his bulls and cows, again in Joseph Califano’s book, which is so disgusting I can’t actually repeat it here (my mother reads these articles). Just imagine hardcore bovine erotica written by Yosemite Sam.

Johnson’s reputation was ruined by 1968 – the disastrous Tet offensive in Vietnam, riots throughout the US, and the assassination of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King contributed to the idea that the country was falling apart, as demonstrated by a haunting Richard Nixon attack ad. Johnson didn’t seek re-election, and instead retreated back to his Texan ranch. He survived just four years after leaving the White House, dying on 22 January 1973, at 64 years old.

In today’s climate, where politics is portrayed as a game of winners and losers and not as a system designed to benefit the actual population, there’s something inspirational about Lyndon Johnson. That’s not to say that he didn’t care about optics. He was an incessantly vain man, constantly measuring his achievements against those of former presidents, and feeling inferior. Indeed, there is something tragically ironic that a man as thirsty for glory as Johnson could achieve as much as he did and yet still be a relative unknown in popular culture compared with Kennedy, Eisenhower and even Nixon.

Unlike most presidents, it is hard to come up with a single narrative thread for LBJ. But to me, his presidency represents moral rectitude despite the political consequences. Johnson privately acknowledged that signing the Civil Rights Act would lose the Democrats the south for a generation, but he knew that it had to be done. He spent his vast political capital on the war on poverty not because it was a vote-winner – far from it – but because he saw America’s inequality as a stain on the country. Johnson represents the foolishness of trying to separate leaders into “good” and “bad” – and in a time of increasing polarisation and militancy, this is a vital lesson.

Perfect politicians don’t exist, and awful people are capable of doing great things that benefit millions of people. That is not an excuse for terrible people in politics; it’s rather that politicians are infinitely more complicated than the caricatures we have reduced them to. They are human, they are inconsistent, and they are usually attempting to do what they see as right. By ignoring this we create a political environment that demonises the opposition and sanctifies our own – which denies the humanity of our politicians and, in turn, rewards them for inhumanity.

Jack Bernhardt is a comedy writer.