On Bloomsday, June 16, when the Irish writer James Joyce and his characters Leopold and Molly Bloom are celebrated, we should also think about his daughter Lucia.

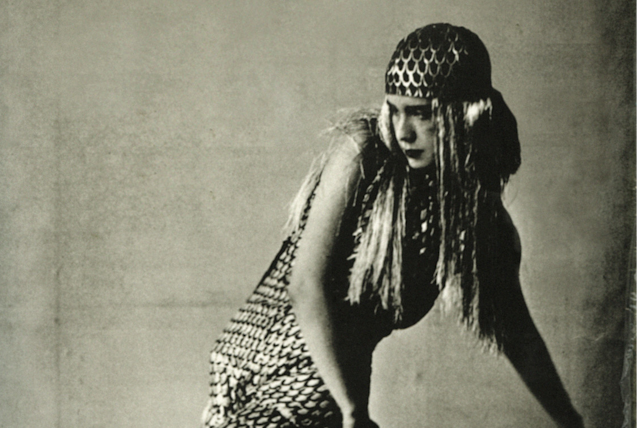

Lucia Joyce, who was born in Trieste in 1907 and died in a sanatorium in Northampton in 1982, has enjoyed and endured near constant critical and popular attention over the years. But we don’t really know much about her at all. She danced passionately, taking lessons with the best teachers in Paris and wowing the audience at a 1929 recital at the Bullier Ball (the image above is from that recital). She dated Samuel Beckett, briefly. She underwent therapy with Jung (who had, incidentally, been scathing of her father’s work). She was hospitalised for schizophrenia in the 1930s. And she was a huge influence on her father while he wrote Finnegans Wake.

But beyond this, Joyce remains something of a mystery. Very little reliable information about her survives: due to the difficulties her schizophrenia caused within the family, letters both about and by her were deliberately destroyed (in addition, as executor of the Joyce estate, her nephew Stephen Joyce had a record of blocking studies about her). Carol Loeb Shloss’ biography Lucia Joyce: To Dance to the Wake remains the leading reference work about her, yet its flaws have been identified by scholars including Hermione Lee.

Fact or fiction?

Where does this leave those of us who want to know more about the woman behind the myth? In the absence of reliable archival materials, one option is to turn to fiction. Back in 1991, Alison Leslie Gold published The Clairvoyant: A Novel of the Imagined Life of Lucia Joyce. More recently, Dotter of her Father’s Eyes, the 2012 graphic novel by Mary and Brian Talbot, compared the upbringings of Lucia and Mary (whose father was the prominent Joyce scholar, James S Atherton). Like many discussions of Joyce, it focuses exclusively on her life prior to her hospitalisation.

In 2015, Annabel Abbs’ The Joyce Girl won the Impress Prize for New Writing and most recently, in June 2018, Alex Pheby published Lucia. I expect there will be plenty of reviews to be read over coming weeks.

While these are provocative, fluent and entertaining works, it’s also true that they display some anxiety about representing Joyce through fiction. The Clairvoyant ends with a brief “author’s afterword” in which Gold offers details of Joyce’s real life, as if concerned that her fiction cannot exist without the scaffolding of facts, even sparse ones. Yet Gold’s prefatory note: “The publisher wishes to draw attention to the fact that the language and spelling in this work is deliberately unconventional,” is much more playful than Pheby’s, which betrays something of the perils of writing about Joyce while her nephew continues to exert stifling control over her legacy:

Any representations of actual persons are either coincidental, or have been altered for artistic effect.

His daughter’s father

The reason for caution transpires early in the novel: like Abbs, Pheby makes incest a central feature of his story. Gossip, hearsay and scandal attached themselves to Joyce throughout her life: do these novels now celebrate her, or her reputation? They attempt to reclaim her, yet without the supporting facts they can at best be imaginative and partial.

Such works purport to separate her from her father, but as the title of the Talbot’s graphic novel – a line from Finnegans Wake shows – this is hard to achieve. The uncomfortable truth is that, beyond her role in the Paris dance scene of the 1920s or her influence on the Wake, were it not for her father she simply would not be of interest to us now. These fictional works still only see Joyce in her father’s shadow. Her dancing led one reviewer, in 1928, to claim that “James Joyce may yet be known as his daughter’s father”.

That day has not come. By contrast, with a swell of works devoted to her in recent years, we may be at risk of a “Lucia industry”, comparable – though on a smaller scale – to the “Joyce industry” that her father precipitated in the academy. The problem is not that we undervalue Joyce, but that we read more into her than is justified.

“No one that has raised up a family has failed utterly in my opinion”, wrote James Joyce to his mother in 1903, in a letter that is, sadly, not available online. Despite the criticisms of the author and his wife Nora Barnacle over their handling of their daughter’s condition, he was devoted to his daughter. Nora, though, never once visited her in hospital.

Neglected by her family, Joyce has nonetheless been extensively attended to by writers. The Clairvoyant ends with an imaginary narrative called: “‘The Story of the Blotting-Paper Girl (Keep them guessing for 300 years)’, A Memoir by Lucia Joyce”. This alludes to her father’s quip about Ulysses, that he’d put enough enigmas in it to “keep the professors busy for centuries”. It seems we’re still working out the puzzle of Lucia Joyce.