Why 19th-Century Axe Murderer Lizzie Borden Was Found Not Guilty

Nativism, gender stereotypes and wealth all played a role in letting Borden, the prime suspect in her father and stepmother’s violent deaths, go free

:focal(407x160:408x161)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/cf/f6cf2496-05a9-43d7-b4cc-9383ecc70399/lizze-borden-letterboxed.jpg)

The Lizzie Borden murder case abides as one of the most famous in American criminal history. New England’s crime of the Gilded Age, its seeming senselessness captivated the national press. And the horrible identity of the murderer was immortalized by the children’s rhyme passed down across generations.

Lizzie Borden took an axe,

And gave her mother forty whacks.

When she saw what she had done,

She gave her father forty-one.

While there is no doubt that Lizzie Borden committed the murders, the rhyme is not quite correct: sixty-four-year-old Abby was Lizzie’s stepmother and a hatchet, rather than an axe, served as the weapon. And fewer than half the blows of the rhyme actually battered the victims—19 rained down on Abby and ten more rendered 69-year-old Andrew’s face unrecognizable. Still, the rhyme does accurately record the sequence of the murders, which took place approximately an hour and a half apart on the morning of August 4, 1892.

Part of the puzzle of why we still remember Lizzie’s crime lies in Fall River, Massachusetts, a textile mill town 50 miles south of Boston. Fall River was rocked not only by the sheer brutality of the crime, but also by who its victims were. Cultural, religious, class, ethnic, and gender divisions in the town would shape debates over Lizzie’s guilt or innocence—and draw the whole country into the case.

In the early hours after the discovery of the bodies, people only knew that the assassin struck the victims at home, in broad daylight, on a busy street, one block from the city’s business district. There was no evident motive—no robbery or sexual assault, for example. Neighbors and passersby heard nothing. No one saw a suspect enter or leave the Borden property.

Moreover, Andrew Borden was no ordinary citizen. Like other Fall River Bordens, he possessed wealth and standing. He had invested in mills, banks, and real estate. But Andrew had never made a show of his good fortune. He lived in a modest house on an unfashionable street instead of on “The Hill,” Fall River’s lofty, leafy, silk-stocking enclave.

Thirty-two-year-old Lizzie, who lived at home, longed to reside on The Hill. She knew her father could afford to move away from a neighborhood increasingly dominated by Catholic immigrants.

It wasn’t an accident, then, that police initially considered the murders a male crime, probably committed by a “foreigner.” Within a few hours of the murders, police arrested their first suspect: an innocent Portuguese immigrant.

Likewise, Lizzie had absorbed elements of the city’s rampant nativism. On the day of the murders, Lizzie claimed that she came into the house from the barn and discovered her father’s body. She yelled for the Bordens’ 26-year-old Irish servant, Bridget “Maggie” Sullivan, who was resting in her third-floor room. She told Maggie that she needed a doctor and sent the servant across the street to the family physician’s house. He was not at home. Lizzie then told Maggie to get a friend down the street.

Yet Lizzie never sent the servant to the Irish immigrant doctor who lived right next door. He had an impressive educational background and served as Fall River’s city physician. Nor did Lizzie seek the help of a French Canadian doctor who lived diagonally behind the Bordens. Only a Yankee doctor would do.

These same divisions played into keeping Lizzie off the suspect list at first. She was, after all, a Sunday school teacher at her wealthy Central Congregational Church. People of her class could not accept that a person like Lizzie would slaughter her parents.

But during the interrogation, Lizzie’s answers to different police officers shifted. And her inability to summon a single tear aroused police suspicion. Then an officer discovered that Lizzie had tried to purchase deadly prussic acid a day before the murders in a nearby drugstore.

Another piece of the story is how, as Fall River’s immigrant population surged, more Irishmen turned to policing. On the day of the murders, Irish police were among the dozen or so who took control of the Borden house and property. Some interviewed Lizzie. One even interrogated her in her bedroom! Lizzie was not used to being held to account by people she considered beneath her.

The Lizzie Borden case quickly became a flash point in an Irish insurgency in the city. The shifting composition of the police force, combined with the election of the city’s second Irish mayor, Dr. John Coughlin were all pieces of a challenge to native-born control.

Coughlin’s newspaper Fall River Globe was a militant working-class Irish daily that assailed mill owners. Soon after the murders it focused its class combativeness on Lizzie’s guilt. Among other things, it promoted rumors that Bordens on the Hill were pooling millions to ensure that Lizzie would never be convicted. By contrast, the Hill’s house organ, the Fall River Evening News, defended Lizzie’s innocence.

Five days after the murders, authorities convened an inquest, and Lizzie took the stand each day: The inquest was the only time she testified in court under oath.

Even more than the heap of inconsistencies that police compiled, Lizzie’s testimony led her into a briar patch of seeming self-incrimination. Lizzie did not have a defense lawyer during what was a closed inquiry. But she was not without defenders. The family doctor, who staunchly believed in Lizzie’s innocence, testified that after the murders he prescribed a double dose of morphine to help her sleep. Its side effects, he claimed, could account for Lizzie’s confusion. Her 41-year-old spinster sister Emma, who also lived at home, claimed that the sisters harbored no anger toward their stepmother.

Yet the police investigation, and the family and neighbors who gave interviews to newspapers, suggested otherwise. With her sister Emma 15 miles away on vacation, Lizzie and Bridget Sullivan were the only ones left at home with Abby after Andrew left on his morning business rounds. Bridget was outside washing windows when Abby was slaughtered in the second floor guest room. While Andrew Borden was bludgeoned in the first floor sitting room shortly after his return, the servant was resting in her attic room. Unable to account consistently for Lizzie’s movements, the judge, district attorney, and police marshal determined that Lizzie was “probably guilty.”

Lizzie was arrested on August 11, one week after the murders. The judge sent Lizzie to the county jail. This privileged suspect found herself confined to a cheerless 9 ½-by-7 ½ foot cell for the next nine months.

Lizzie’s arrest provoked an uproar that quickly became national. Women’s groups rallied to Lizzie’s side, especially the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and suffragists. Lizzie’s supporters protested that at trial she would not be judged by a jury of her peers because women, as non-voters, did not have the right to serve on juries.

Lizzie could afford the best legal representation throughout her ordeal. During the preliminary hearing, one of Boston’s most prominent defense lawyers joined the family attorney to advocate for her innocence. The small courtroom above the police station was packed with Lizzie’s supporters, particularly women from The Hill. At times they were buoyed by testimony, at others unsettled. For example, a Harvard chemist reported that he found no blood on two axes and two hatchets that police retrieved from the cellar. Lizzie had turned over to the police, two days after the murders, the dress she allegedly wore on the morning of August 4. It had only a minuscule spot of blood on the hem.

Her attorneys stressed that the prosecution offered no murder weapon and possessed no bloody clothes. As to the prussic acid, Lizzie was a victim of misidentification, they claimed. In addition, throughout the Borden saga, her legion of supporters was unable to consider what they saw as culturally inconceivable: a well-bred virtuous Victorian woman—a “Protestant nun,” to use the words of the national president of the WCTU—could never commit patricide.

The reference to the Protestant nun raises the issue of the growing numbers of native-born women in late 19th-century New England who remained single. The research of women historians has documented how the label “spinster” obscured the diverse reasons why women remained single. For some, the ideal of virtuous Victorian womanhood was unrealistic, even oppressive. It defined the “true woman” as morally pure, physically delicate, and socially respectable. Preferably she married and had children. But some women saw new educational opportunities and self-supporting independence as an attainable goal. (Nearly all of the so-called Seven Sisters colleges were founded between the 1870s and 1890s; four were in Massachusetts.) Still, other women simply could not trust that they would choose the right man for a life of marriage.

As to the Borden sisters, Emma fit the stereotype of a spinster. On her deathbed their mother made Emma promise that she would look after “baby Lizzie.” She seems to have devoted her life to her younger sister. Lizzie, though not a reformer of the class social ills of her era, acquired the public profile of Fall River’s most prominent Protestant nun. Unlike Emma, Lizzie was engaged in varied religious and social activities from the WCTU to the Christian Endeavor, which supported Sunday schools. She also served on the board of the Fall River Hospital.

At the preliminary hearing Lizzie’s defense attorney delivered a rousing closing argument. Her partisans erupted into loud applause. It was to no avail. The judge determined she was probably guilty and should remain jailed until a Superior Court trial.

Neither the attorney general, who typically prosecuted capital crimes, nor the district attorney were eager to haul Lizzie into Superior Court, though both believed in her guilt. There were holes in the police’s evidence. And while Lizzie’s place in the local order was unassailable, her arrest had also provoked a groundswell of support.

Though he did not have to, the district attorney brought the case before a grand jury in November. He was not sure he would secure an indictment. Twenty-three jurors convened to hear the case on the charges of murder. They adjourned with no action. Then the grand jury reconvened on December 1 and heard dramatic testimony.

Alice Russell, a single, pious 40-year-old member of Central Congregational, was Lizzie’s close friend. Shortly after Andrew had been killed, Lizzie sent Bridget Sullivan to summon Alice. Then Alice had slept in the Borden house for several nights after the murders, with the brutalized victims stretched out on mortician boards in the dining room. Russell had testified at the inquest, preliminary hearing, and earlier before the grand jury. But she had never disclosed one important detail. Distressed over her omission, she consulted a lawyer who said she had to tell the district attorney. On December 1, Russell returned to the grand jury. She testified that on the Sunday morning after the murders, Lizzie pulled a dress from a shelf in the pantry closet and proceeded to burn it in the cast iron coal stove. The grand jury indicted Lizzie the next day.

Still, the attorney general and the district attorney dragged their feet. The attorney general bowed out of the case in April. He had been sick and his doctor conveniently said that he could not withstand the demands of the Borden trial. In his place he chose a district attorney from north of Boston to co-prosecute with Hosea Knowlton, the Bristol County District Attorney, who emerged as the trial’s profile in courage.

Knowlton believed in Lizzie’s guilt but realized there were long odds against conviction. Yet he was convinced that he had a duty to prosecute, and did so with skill and passion exemplified by his five-hour closing argument. A leading New York reporter, who believed in Lizzie’s innocence, wrote that the district attorney’s “eloquent appeal to the jury … entitles him to rank with the ablest advocates of the day.” Knowlton thought a hung jury was within his grasp. It might satisfy both those convinced Lizzie was innocent and those persuaded of her guilt. If new evidence emerged, Lizzie could be retried.

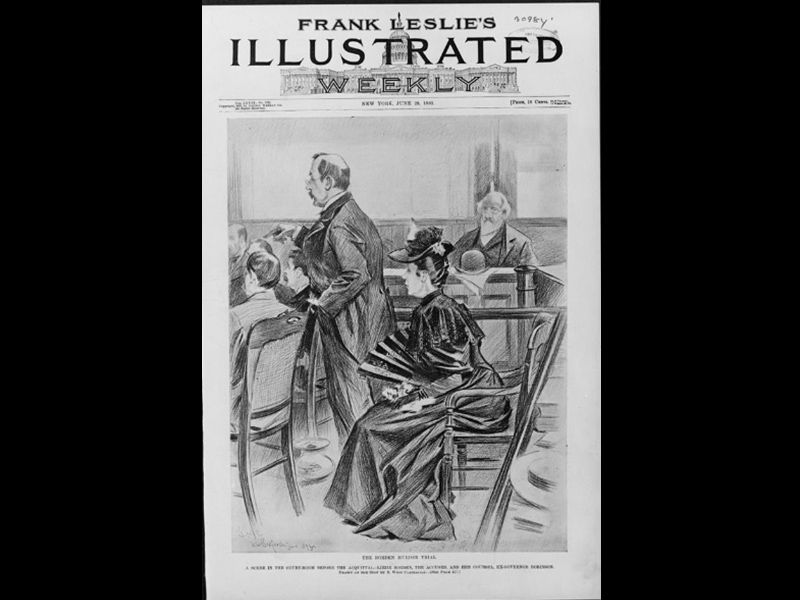

The district attorney perhaps underestimated the legal and cultural impediments he faced. Lizzie’s demeanor in court, which District Attorney Knowlton perhaps failed to fully anticipate, also surely influenced the outcome. Here lies a gender paradox of Lizzie’s trial. In a courtroom where men reserved all the legal power, Lizzie was not a helpless maiden. She only needed to present herself as one. Her lawyers told her to dress in black. She appeared in court tightly corseted, dressed in flowing clothes, and holding a bouquet of flowers in one hand and a fan in the other. One newspaper described her as “quiet, modest, and well-bred,” far from a “brawny, big, muscular, hard-faced, coarse-looking girl.” Another stressed that she lacked “Amazonian proportions.” She could not possess the physical strength, let alone the moral degeneracy, to wield a weapon with skull-cracking force.

Moreover, with her father’s money in hand, Lizzie could afford the best legal team to defend her, including a former Massachusetts governor who had appointed one of the three justices who would preside over the case. That justice delivered a slanted charge to the jury, which one major newspaper described as “a plea for the innocent!” The justices took other actions that stymied the prosecution, excluding testimony about prussic acid because the prosecution had not refuted that the deadly poison might be used for innocent purposes.

Finally, the jury itself presented the prosecution with a formidable hurdle. Fall River was excluded from the jury pool, which was thus tilted toward the county’s small, heavily agricultural towns. Half of the jurors were farmers; others were tradesmen. One owned a metal factory in New Bedford. Most were practicing Protestants, some with daughters approximately Lizzie’s age. A sole Irishman made it through the jury selection process. Not surprisingly the jury quickly decided to acquit her. Then they waited for an hour so that it would appear that they had not made a hasty decision.

The courtroom audience, the bulk of the press, and women’s groups cheered Lizzie’s acquittal. But her life was altered forever. Two months after the innocent verdict, Lizzie and Emma moved to a large Victorian house on The Hill. Yet many people there and in the Central Congregational Church shunned her. Lizzie became Fall River’s curio, followed by street urchins and stared down whenever she appeared in public. She withdrew to her home. Even there, neighborhood kids pestered Lizzie with pranks. Four years after her acquittal a warrant was issued for her arrest in Providence. She was charged with shoplifting and apparently made restitution.

Lizzie enjoyed traveling to Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C., dining in style and attending the theater. She and Emma had a falling out in 1904. Emma left the house in 1905 and evidently the sisters never saw each other again. Both died in 1927, Lizzie first and Emma nine days later. They were interred next to their father.

Joseph Conforti was born and raised in Fall River, Massachusetts. He taught New England history at the University of Southern Maine and has published several books on New England history, including Lizzie Borden on Trial: Murder, Ethnicity, and Gender.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.