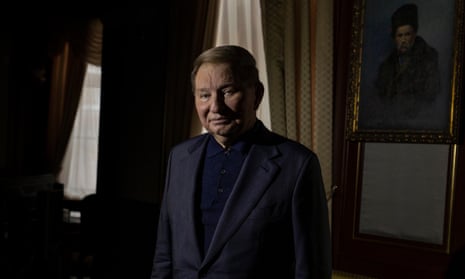

Ukraine’s former president Leonid Kuchma has warned that the US “will lose face before the entire world” if it abandons Kyiv, and said mistakes by the west contributed to Vladimir Putin’s all-out invasion last year.

In his first interview with a western publication since 2015, Kuchma described Putin as a career KGB operative. “It’s his profession, with everything that implies,” he said, adding: “People say his obsession with Ukraine is a kind of mania or mental disorder. Maybe it’s true.”

On 24 February 2022, Kuchma and his wife, Lyudmila, were in the centre of Kyiv as Russia attacked. “I was sure Putin was capable of invading but not sure whether he would decide to invade,” he said. That morning they woke to explosions. “It was terrible, a shock. I saw two bombers flying over my head in the street.”

Putin’s goal was not only to seize land but to destroy the “concept” of Ukraine itself, as a “competitive alternative to Russia”, he said. “The proof of this is the terrible human losses and reputational sacrifices that Putin is willing to make for this,” he suggested.

Kuchma – a Russian-speaker from Ukraine’s industrial south-east and the ex-director of a Soviet rocket factory – was president of Ukraine between 1994 and 2005. He signed two historic agreements with Russia that guaranteed Ukraine’s post-USSR borders: the 1995 Budapest Memorandum and a 1997 treaty of friendship, negotiated with Boris Yeltsin, with whom he had good relations, and ratified by the Duma.

The first indication of Moscow’s revisionist ambitions came in 2003, Kuchma said. Putin, Russia’s new president, laid claim to the small island of Tuzla in the Black Sea, between Crimea and the Russian mainland. On this occasion Putin backed down. He gave further “clear signals” of his intention to expand Russia’s borders by force when he sent troops in 2008 into neighbouring Georgia. He followed this up in spring 2014 by seizing Crimea.

“It was extremely unpleasant that the world didn’t react. It was silent,” Kuchma said. “Putin understood that he could do anything because there was no principled response.” Russia was able to seize further territory in the eastern Donbas region, he explained, beginning an almost decade-long Russo-Ukrainian war.

Last week Kuchma said he turned on the TV at 3am and watched Republicans in the US Senate vote down a $61bn package of assistance for Ukraine. The Biden administration has warned that without further US military aid Putin will “prevail” on the battlefield, where Ukrainian troops are already running short of ammunition.

“We have to hope Biden can get the legislation through. The US has lost Afghanistan. Defeat for Ukraine means the US loses face before the entire world,” Kuchma said. Asked if Kyiv could win, at a time when international solidarity appears to be waning, he replied: “I believe in victory. I can’t exist in any other way.”

The former president said it was unrealistic to think Putin would agree to peace talks. He has already declared that four Ukrainian provinces in the south and east “belong” to Russia, even though they are only partly under Moscow’s control.

He added: “Putin can’t sign a document which states that he didn’t get what he wanted [in Ukraine]. He would have to explain this to the Russian people. He’s the leader of Russia.”

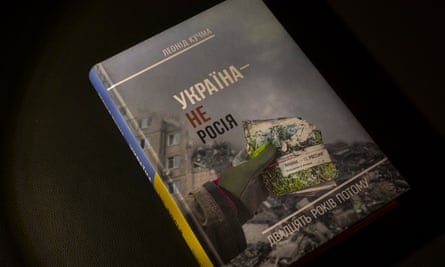

Last month Kuchma, 85, published an updated edition of Ukraine is Not Russia, a book he wrote in 2003. The original edition was addressed to Russians and Ukrainians. Much of it now looks prophetic. He complained that Russian politicians saw his country as an “indivisible part of Russia”. They regarded Ukrainians as “yokels” and “country cousins”, with a quaint “ethnographic” culture.

The new version of Kuchma’s book concedes that his efforts to enlighten ordinary Russians were “in vain”. They overwhelmingly supported Putin’s “aggression” and “imperialist” so-called special operation, he said.

Asked why Ukraine resisted Russia last year, to the Kremlin’s surprise, Kuchma answered: “Because Russians are not Ukrainians. They have a different mentality.” He said the Russian way of thinking derived from the Mongols, who ruled early Moscow. Ukraine, by contrast, originated with Kyivan Rus, the ninth-century Orthodox princedom, whose legacy Putin controversially claims.

“For centuries the west saw Ukraine exclusively through a Russian lens,” Kuchma said, adding that Moscow used its size and natural resources to “hypnotise” and “bluff” foreign leaders. Kuchma said he had never been “anti-Russian” as a person and politician. He had tried to establish friendly – and equal – relations. This proved impossible because Russia under Putin wanted “integration” rather than cooperation.

The book details Kuchma’s wartime childhood, growing up in a rustic village in Polesia, a northern forested region near the border with today’s Belarus. His father died fighting the Nazis. Kuchma’s widowed mother was a schoolteacher. Their family was poor. He carried water, tended the vegetable patch and grazed cows.

after newsletter promotion

In the 1950s he studied physics and became active in communist politics. Kuchma met his Russian wife at an organised weeding expedition. He became the director of Yuzhmash, Europe’s largest missile factory. In the 1980s his awareness that he was Ukrainian and not Russian grew. After the Soviet Union fell apart, Kuchma became a Ukrainian MP, then prime minister and president.

Critics accuse him of enabling oligarchs. One scandal haunted his administration. In 2000 the Georgian-Ukrainian journalist Georgiy Gongadze was kidnapped and murdered. His headless body was found in woods outside Kyiv. Tapes surfaced during which Kuchma allegedly discussed “silencing” Gongadze with senior aides. Four interior ministry officials were subsequently convicted of the killing. He denied involvement or appearing on the tapes.

Supporters say he managed relations with Moscow more deftly than his successors. Kuchma’s last controversial term in office ended with the 2004 Orange Revolution, brought about in part by the fallout from the Gongadze affair and amid accusations of authoritarianism and government thuggery. Thousands of protesters camped out in Kyiv’s Maidan Square after Viktor Yanukovych, the Russian-backed candidate, whom Kuchma supported, fraudulently declared victory following presidential elections.

Kuchma said Putin “directly urged me to use force” against unarmed demonstrators. “I categorically refused,” he told the Guardian. Yanukovych lost a rerun vote and became president in 2010. In 2014, faced with another Maidan uprising, Yanukovych was under similar pressure from Moscow. His security forces shot dead 100 people. “Putin managed to persuade Yanukovyich to commit this crime. I have no doubt that it was their joint decision, a bilateral one,” Kuchma said.

Afterwards, Yanukovuch fled to Russia and Putin began his Ukraine land-grab. In 2019, Volodymyr Zelenskiy defeated Yanukovych’s replacement, the oligarch Petro Poroshenko. “Ukraine is lucky to have Zelenskiy. In my analysis he is a sincere person. He was invited to leave Ukraine [when the Russians closed in on Kyiv] but stayed,” Kuchma noted.

Politics has returned in recent months in the wake of Ukraine’s failed counter-offensive, and as an exhausted population grows ever more tired of war. Zelenskiy has ruled out holding elections next year. Kuchma said this was correct. “Our homes are being bombed. Soldiers are in trenches. Five million Ukrainians live in Europe. You can’t ask people to go out and vote in these circumstances. It’s absurd,” he said, adding: “If they did happen I’m sure Zelenskiy would win.”

There was no prospect Russia and Ukraine could be reconciled, he said. The full-scale war had “united” Ukraine and erased the “contradictions” that used to exist during his presidency between eastern and western regions. “People hate Russia because of the suffering and loss. So many Ukrainians have died or got wounded.” Ukraine’s future was with the EU and Nato, he said, and not as part of a rebooted Russian empire.

He finished with a warning to the west, and to those contemplating leaving Ukraine to its difficult fate. “I want to say only one thing: we will not retreat. We will stand until the end,” he said. “We will never give up – no way. If you help us, we will win. If you stop helping us, we can die.” He added: “But then you will be the next ones Russia wants to destroy.”