When Lee Hazlewood died from renal cancer in 2007, his obituarists had a complicated story to tell: his enormous success as a hitmaker for Nancy Sinatra in the 1960s, his relocation to Sweden in the 70s, his neglected solo career, his long semi-retirement and his belated return to the music industry, feted by the likes of Nick Cave, Jarvis Cocker and Sonic Youth. The pieces didn't quite fit together. He was funny, charismatic and supportive but he could also be cold, vengeful and mean. Like Serge Gainsbourg, he made both exquisitely subversive pop music and cynical kitsch, and gave the impression that he regarded his career as a private joke with financial benefits. The only niche he inhabited was the one he carved for himself, and that could get lonely.

Barely acknowledged in the obituaries, however, was Lee Hazlewood Industries (LHI), the label he ran from 1966 to 1971. Neither commercially fruitful nor critically acclaimed, most of its 305-song output, which pinballed between country, soul, girl groups, psychedelia and novelty pop, fell through the cracks of history, almost as if it had never existed. Now reissue specialists Light in the Attic have salvaged it all in an epic box set, There's a Dream I've Been Saving, which tells the story of a label that could only have existed in a particular era of the Los Angeles music business, under the aegis of a very unusual man.

When I met him in 2002, the 72-year-old was a cranky raconteur with a taste for gruff one-liners. I asked him what inspired him to enter the music business. "Poverty," he growled, lighting a Marlboro. "I had a couple a dozen jobs in my life and I didn't like any of 'em."

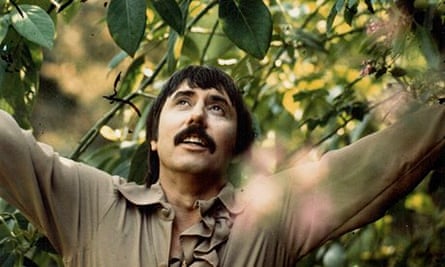

Born in 1929, the son of an itinerant Oklahoma oilman, Hazlewood made a small fortune as a songwriter and producer for Duane Eddy before Frank Sinatra cajoled him into relaunching his daughter Nancy's flatlining career. Thanks in part to Hazlewood's unorthodox vocal coaching ("Sing like a 14-year-old girl who fucks truck-drivers"), 1966's These Boots Are Made for Walkin' was a colossal hit, earning Hazlewood the lasting gratitude of Frank and a generous offer from Decca: his own label, no strings attached. "Lee was great at taking advantage of situations, especially when they involved getting free money," says Suzi Jane Hokom, his colleague and lover throughout the label's lifetime.

This article includes content provided by Spotify. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

It was an exhilarating time to be in LA. The city was full of money, music and the conviction that everyone was just one hit away from the big time. Hazlewood met the 20-year-old Hokom at the Hollywood restaurant Martoni's, a bustling music industry hangout. "He was funny and charming and he thought I was great because here was this girl singer who wanted to be a record producer," she says. "He thought that was unusual. It was a mutual admiration society."

She joined LHI as singer, producer and graphic designer; eventually they fell in love. "He used to call himself a grey-haired sonofabitch. It was a caricature he created. He liked to talk like a country guy who didn't have a dime, but then if he bought a car it had to be the biggest, longest car." It was a turbulent relationship. The label's logo, a classical Greek profile, was based on a necklace Hazlewood bought for Hokom while on holiday in Mexico. When she loaned it to Light in the Attic to photograph for the box set, she had to explain that it was chipped when she threw it at him during a heated spat.

Hazlewood had a nose for untested talent. He offered Texas-born radio DJ Tom Thacker the job of vice-president after a game of football at a friend's house. He was an unorthodox boss. His private office had blackout blinds and he liked to turn up for work around midday. One morning he came in early and found Thacker already at his desk. "Have you ever been late a day in your life?" he asked. No, said Thacker. "Well have you ever missed a day?" No. Horrified, Hazlewood ordered him to take the rest of the day off. "It was the best time in my life," says Thacker. "He was fun to work for. Real easy. It didn't seem to matter where Lee went, he could always find a parking place when no one else could."

Hazlewood liked to sign people he met around town or who turned up unannounced at 900 Sunset Boulevard, including Detroit girl group Mama Cats, whom he renamed Honey Ltd. "He had the deepest voice I'd ever heard in my life," says the band's Alex Sliwin. "I couldn't even understand him. And I'd never seen anyone with a moustache like that. He was very Texan. He was very sweet and embracing of us: his 'little darlin's'."

Even before becoming a fully independent label in 1968, LHI operated like one, prizing speed, spontaneity and instinct. LHI signed artists at such a rate that even the staff couldn't keep track. When I ask Thacker about Hamilton Streetcar, who recorded the loopy psych-pop single Invisible People ("They're gonna get you baby! They're gonna make you invisible too!"), he doesn't know who I'm talking about. Hazlewood's approach was to record singles as quickly and cheaply as possible and hope some of them took off. "It didn't matter about the style," says Thacker. "It was whatever sounded good and sounded like it could be a hit."

"It was like, OK, crank this out," says Hokom. "For me it was terrifying because I'm a perfectionist. It was challenging, especially when you're the only girl who's doing that." Fortunately LHI's studio talent pool included future TV theme-tune maestro Mike Post, Phil Spector protege Jack Nitzsche and some of the ubiquitous LA session musicians known as the Wrecking Crew.

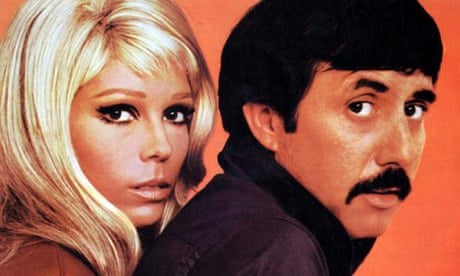

It was a well-oiled machine but it wasn't producing the goods. Even as Hazlewood continued to fare well outside the label with Nancy Sinatra – songs such as Some Velvet Morning and Sugar Town smuggled X-rated sentiments into the Top 40 – LHI artists came and went, and even his beloved Honey Ltd fizzled out. The only signing who went on to bigger things was country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons, who left the International Submarine Band after their Hokom-produced 1968 album to join the Byrds. Hazlewood, who never liked Parsons, was so enraged that he sued to have the singer's vocals removed from the Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo.

He was just as controlling when Hokom received an offer to meet the Beatles (he hated them, too) in New York to discuss producing artists on their new Apple label. "That was an absolute no," says Hokom, who stormed out and went to New York anyway, just for the experience. "Lee was a very possessive man and the Beatles were kind of intimidating to someone who likes to say he's not intimidated by anyone."

To most of his colleagues, Hazlewood continued to appear wry and unflappable even as LHI's chronic hit-drought threatened its survival. "He must have had his moments but did I ever see one? No," says Honey Ltd's Joan Glasser. "I have no recollection of him showing any anger or remorse about anything. He was a survivor. He rolled with everything." Glasser's husband, who recorded and produced for LHI as Michael Gram, says, "Tom and Lee were incredible. They made you feel like a human being."

Hazlewood's inner circle, however, witnessed a more vulnerable side. "When the money started running low we started figuring what are we gonna do?" says Thacker. "There were tears and all kinds of angst over the failure of the label because we were young, we were hopeful, we were invincible, and when we didn't get hits we were terribly disappointed."

By the end of the 60s, Hazlewood could no longer find a parking place in the LA music business but, to his surprise, he had become a celebrity overseas. En route to Russia in 1969 to accept a wood cabin in honour of These Boots Are Made for Walkin', he stopped off in Sweden and met director Torbjörn Axelman, another energetic, hard-living rogue. They became lifelong friends. "Lee was a cowboy all through," says Axelman via email. "He was a great entertainer and storyteller. I miss him a lot."

While working with Axelman on the peculiar 1970 TV special Cowboy in Sweden, Hazlewood began an affair with co-star Lena Edling. Hokom had finally had enough and walked. By that point Hazlewood had tax problems, his teenage son was almost old enough for the Vietnam draft, and LHI was dying anyway, so Sweden looked like the perfect escape route. He spent the rest of the decade there, making increasingly strange records and films with Axelman.

Was Thacker surprised by the move? "Nothing about Lee really surprised me. He was a very spontaneous human being."

"I think he knew he'd burned his bridges in LA and here was a brand new world where he had a built-in fanclub," says Hokom. "You have to make friends with people in this town. Instead of maintaining his friendships he kind of abandoned them. He could detach himself from things that weren't going his way. I think he left a lot of these little broken bits around. He really needed a new start." ("He could be distant and he could be extremely sweet," Thacker responds. "I just thought of it as artistic moods.")

There was one last piece of unfinished business, emotional rather than financial. In 1971, Hazlewood recorded his finest work, a mordant breakup album called Requiem for an Almost Lady. When I met him he laughed off the idea that it was all about Hokom: "I've had my pocketbook bent but I've never had my heart broken."

But if that's true, then why did he have a finished copy hand-delivered to Hokom's house? "That was the cherry on top," she says with a harsh laugh. "I was shocked. In a way it was hurtful and in a way it was poignant. I had moved on and he was still carrying a torch. Whenever he'd be in town I'd find little love notes slipped under my doormat. It was really sad. He'd be in touch from time to time and we'd go out for dinner. Every time I saw him he seemed a little more down. He drank nothing but Chivas Regal when I was with him and he told me much later that he was drinking a quart of vodka a day. And I said, wow, what happened to Chivas Regal? I think he resigned himself."

Hazlewood sank from view in the 80s and 90s, thwarting attempts by the Sub Pop label to reissue his work and release a heavyweight tribute album featuring fans such as Nirvana and Beck. Later, other labels approached him and he eventually relented, although he admitted that the endorsement of a Cocker or Cave meant less to him than the royalty cheques he got from Billy Ray Cyrus's cornball version of These Boots Are Made for Walkin'. In his final years he became a beloved cult hero – "an obscure old fuck," as he put it – but only now has the rest of the LHI roster been rescued from the shadows.

"These were my friends, people with great dreams," Hokom says wistfully. "This was their moment in the sun and it kind of fell apart. For Lee I think it was just another business venture. I'm not even sure how much his heart was in it after a while." She sighs. She doesn't want to badmouth him ("I stayed with him for six years. There must have been a connection, right?") but he still perplexes, frustrates and saddens her, six years after his death.

"Y'know, he was such an odd fellow and I look back and ask what exactly was it, Suzi Jane, that you saw in this guy? And I think it was his incredible writing. He enamoured me with his imagination. He just had great stories."

There's a Dream I've Been Saving: Lee Hazlewood Industries 1966-1971 is out on Monday on Light in the Attic.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion