Laurie Anderson: ‘Lou Reed was one of the few men I’ve ever met who could cry’

As Lou Reed’s early poems are published for the first time, his widow Laurie Anderson talks to Roderick Stanley (First published in The Times, May 16 2018)

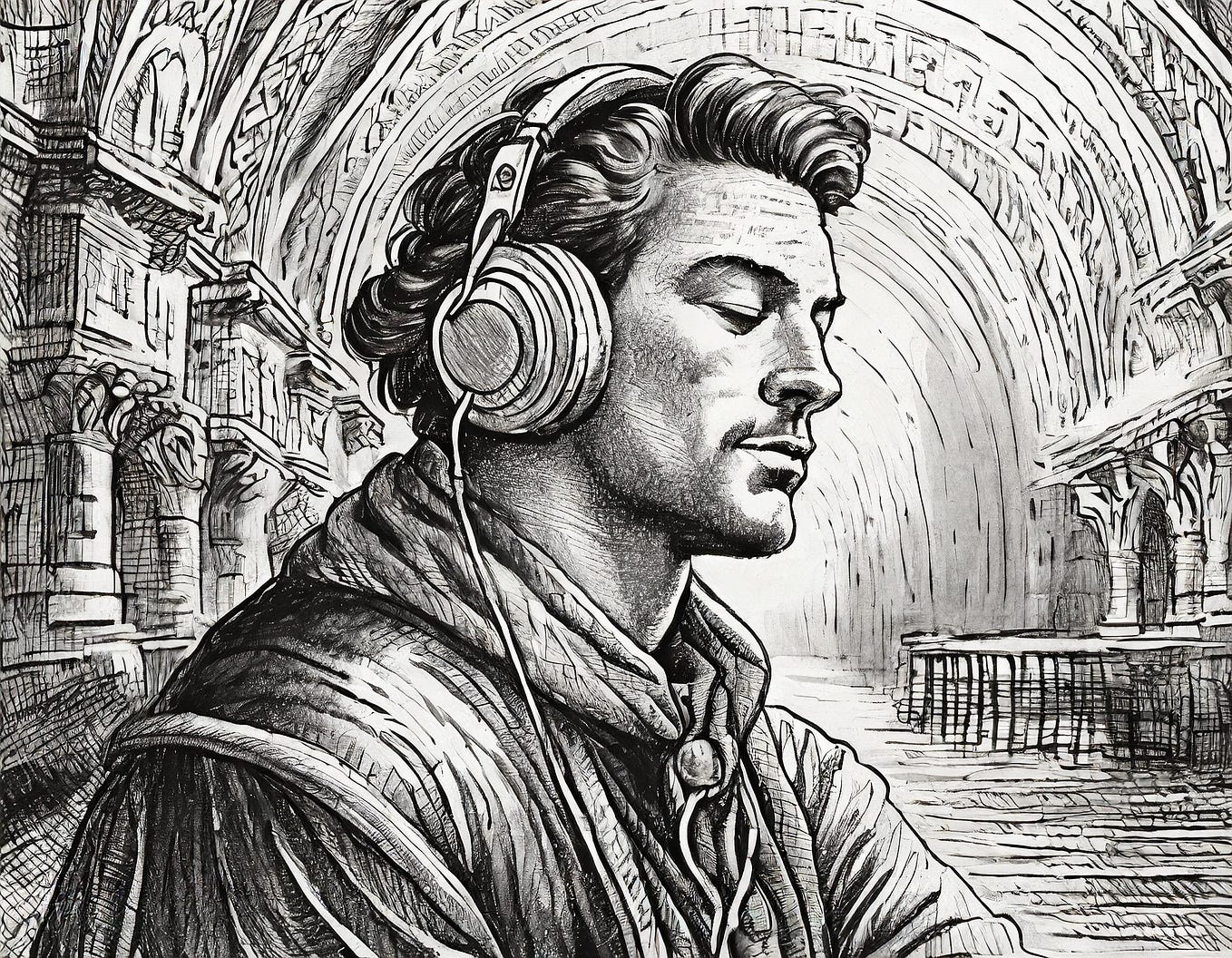

On the evening of March 10, 1971 a familiar, tousle-haired figure took to the stage at a poetry reading in St Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, a New York landmark dating from 1799. Celebrated poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Ted Berrigan were among the hip downtown crowd as 28-year-old Lou Reed, the former singer of an alternative rock band called the Velvet Underground, began to mumble: “This is a poem that got a beautiful layout . . . I was real proud. I said, ‘Hey, man, I’m a poet. Look at that, man.’ ”

Reed was indeed a poet, as a new book published by cultural archivists Anthology Editions confirms, shining a light on the point in Reed’s life just before he embarked on his extraordinary solo musical career. Titled Do Angels Need Haircuts?, it is a slim, clothbound volume drawn from a tape recording Reed made of his performance that night and is the first release from the extensive archives of his life’s work acquired by the New York Public Library last year, after his death in 2013.

“It took us four years to go through it all,” says Laurie Anderson, the celebrated American multimedia artist who first met Reed in 1992; they became a couple soon after and got married in 2008. “This is like getting to know him again. It’s really wonderful. Something most people don’t get to do is meet their younger partner much later in life.”

Anderson’s studio is on the west side of downtown Manhattan, overlooking the Hudson River. Pictures of Reed hang on the walls, along with a large photograph of the Dalai Lama, and a simple rope swing is suspended from the ceiling. It is colourful, bright and homely, with shelves of books about art and music, hinting at her long and varied career. This has straddled performance art, pop (O Superman reached No 2 in the UK charts in 1981), avant-garde electronic music (she invented the tape-bow violin), being Nasa’s first artist-in-residence, collaborating with everyone from William Burroughs to Ryuichi Sakamato, theatre, writing, and directing Oscar-nominated films such as Heart of a Dog in 2015.

In the back office a small, territorial dog makes itself known, sniffs, then scurries away, satisfied. Anderson is scruffily chic, with spiked hair and in a cream blazer, camo-print trousers and leather ankle boots. She smiles all the time, even when reflecting on emotional topics.

”This is like getting to know him again. It’s really wonderful. Something most people don’t get to do is meet their younger partner much later in life.”

Anderson has been working on the archive with the producer Don Fleming, who is also the director of the Alan Lomax field recordings of early American folk and blues; she says that they didn’t want to do a “typical” official collection of poems, “because that’s not what Lou was doing’’. As such, the book also contains transcripts of his banter with the audience, along with photographs, ephemera and a 7” vinyl of the original recording.

The poems echo many of the qualities of Reed’s songs that fans throughout the decades have loved: his sensitive portrayals of society’s outsiders — as in his immortal hit, Walk on the Wild Side in 1972, about the drag queens and night creatures who populated the downtown scene — his unique approach to gender fluidity (“Genuinely like that . . . he didn’t care what you thought”), deliciously vicious streak, and an arguably under-celebrated sense of humour.

“Funniest guy I’ve ever met, he was hilarious,” says Anderson, adding that he was always buying presents for people, even putting them through school. “Lou knew how to take the jacket on and off, he really did. I think it was about hiding his kindness.” The reason he wanted to do that is “vulnerability”, she thinks. “He was one of the few men I’ve ever met who could cry. Men don’t cry, it’s not allowed. But he was terribly emotional. Think of what he wrote — you don’t write that if you don’t feel it.”

One poem begins: “Playing music is not like athletics. One may improve with age.” “Isn’t that interesting?” she says. “It gives you a glimmer of how hard he tried in everything . . . to make a song better, make his experience of the moment better, make his hair look nicer. He always, until the last second he was alive, wanted to make things better. It was crazy. I just hope I’m not idealising him . . . Of course, to some extent I probably am.”

Much of the writing feels taut and contemporary, with lines such as: “We are the people who conceive our destruction and carry it out lawfully. We are the insects of someone else’s thought.” Anderson says: “He was fierce and he was political. Oh, to hear what he would have said about Don [Trump] . . . it would have been completely outrageous, in a way very few people are now.

“It was only a couple years on from the 60s,” she continues, noting that we are now half a century on from 1968 and her own “college revolutionary” days. “Everyone was an activist. The thing is, everything gets bigger, oppression also gets bigger. A lot of my friends in the Occupy movement, they were trailed . . . cars in front of their houses. That movement was crushed.”

“Everything gets bigger, oppression also gets bigger. A lot of my friends in the Occupy movement, they were trailed . . . cars in front of their houses. That movement was crushed”

Of the Me Too movement, she wonders: “Is there any consistency or force to any of this stuff? I’m really hoping young women go, ‘Guess what, it’s not just celebrities.’ All women face that in their job . . . I don’t think I know a single woman who doesn’t have a story like that.

“You don’t think about telling it, because it sounds like sour grapes or something. But I was kicked out of college for that reason.” She is reluctant to be drawn on details but says she reported an incident. “They said, ‘I’m sorry. We just can’t believe that about that guy . . .’ So, I got kicked out.”

Anderson says she was fortunate because she “didn’t have to go into the so-called workplace”, and that, for a while at least, in the art world, “men and women were, at that point, very equal”.

“I’m not trying to say the art world is an equal employer, it’s not. But I was part of a group . . . Trisha Brown, Phil Glass, Gordon Matta-Clark, Susie Harris. None of us thought we’d ever make a dime. When I was starting, you could see all the artists in New York at a party, and it wouldn’t be more than 30 people.” New York at that time was “burned-out and dangerous”, she adds. “A weird scene, really fun. But I’m not sure what I would have thought of Lou at that point. I wasn’t that interested in rock.”

In 2015 Anderson installed a remarkable work in New York’s gargantuan Park Avenue Armory, Habeas Corpus, in which Mohammed el Gharani, a former Guantanamo detainee, appeared from west Africa via live-streamed 3D projection. As the pace of politics and technology accelerates, 2015 now feels like a lifetime ago. “Though it doesn’t feel to me like things are moving fast,” she says. “It feels like they’re stuck. It’s only the shit things that are moving. Like, what did he tweet today? Who cares? It’s always the same thing.”

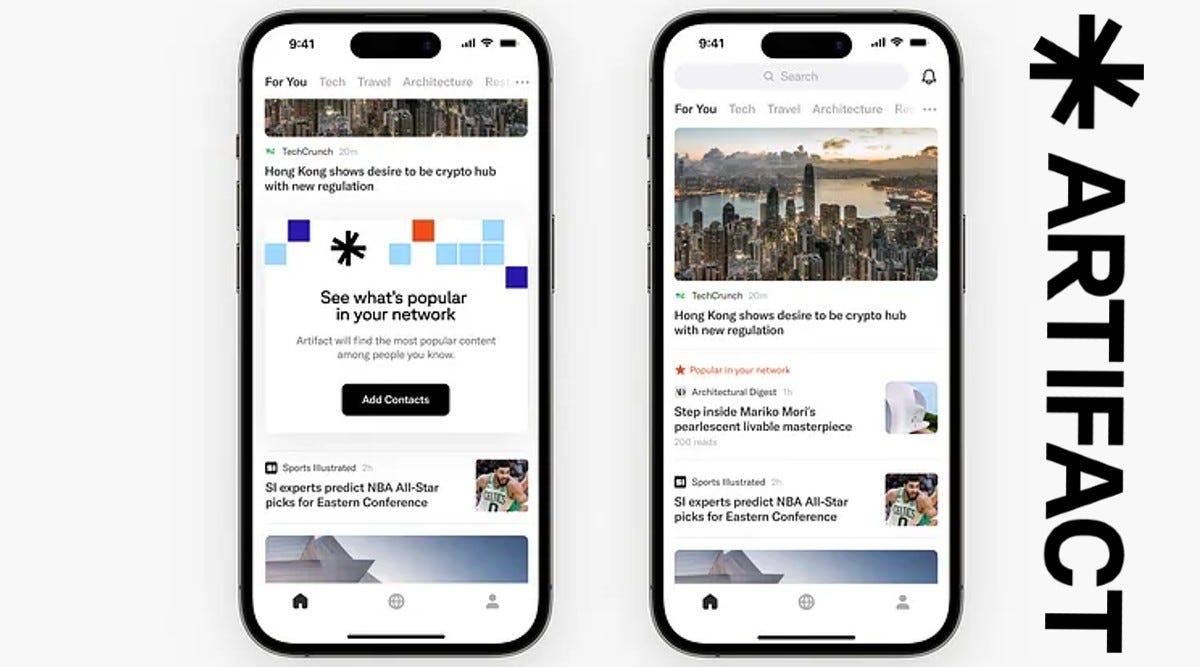

Anderson thinks that tailored news feeds are “insane”, and the prime reason that debate is so polarised. She was always “very suspicious” of technology, she explains, but says it still came as a shock to see how “people are so mean. And so many barriers could fall so fast.” She refers to the anti-Hillary Clinton chants during the Trump campaign: “That you could just start saying shit, and getting a bunch of people to chant, ‘Lock her up! Lock her up!’ That was a big moment for me.”

As someone who has been studying the effects of technology on society since before most, she finds the idea that it is going to save us particularly poisonous. “People are always asking me, as a techy kind of person, ‘What’s going to happen?’ ” she says, referring to climate change. “So I’ve had to learn as much as I could. And I feel pretty dark about it, though I try to restrain myself, because it’s not a great story when you go, ‘Guess what? There’s nothing you can do!’

“At the same time I’m an optimist, weirdly. I suppose it’s the definition of tragedy — you see it coming, it’s wild and bad, and no one can stop it. We’re wrapped up in the tweets! We’re beyond distracted and frazzled. Every time I put my phone down, then pick it up, I’ve got 70 things.”

Anderson recently created an award-winning virtual reality installation called Chalkroom, in which the viewer floats through a haunting edifice of stories, words and letters. She has also created a new album with Kronos Quartet called Landfall, inspired by Hurricane Sandy, which badly damaged New York in 2012. The loss of her basement archive in that natural disaster also inspired her to write the book All the Things I Lost in the Flood. While she is as busy as ever, her new work seems preoccupied with notions of loss and decay.

“I’ve never been good at endings. I don’t know how to write them. I just go, ‘Thanks, goodnight. The show’s over, for no good reason!’ What is this for? Where’s it going? Those are really big questions for me. And I find the things I’m making in the meantime try to stop time in a way, and let you float, let you be timeless and not just ask, ‘What’s going to happen next?’ You just are. You’re free.”

“I’ve never been good at endings. I don’t know how to write them. I just go, ‘Thanks, goodnight. The show’s over, for no good reason!’”

As a medium, virtual reality seems highly suited to where her work has brought her. “I’m geeking out on it. I just love it,” she says. “The project we’re working on now has to do with the moon, I can’t tell you any more, it’s too secret. But if you can imagine your point of view shifting really rapidly . . . It takes my breath away. That’s another thing I know Lou would have really loved is VR. He would be so into this. He’s missing a lot.”

“One of my favourite expressions of Lou’s is, ‘Between thought and expression lies a lifetime,’ which is from a love song [Velvet Underground’s Some Kinda Love]. So, I thought, ‘That’s what it’s taking me, to look at what this archive is.’ My lifetime, his lifetime, looking at it in so many different ways. It’s been pretty mind-blowing.”

Do Angels Need Haircuts? by Lou Reed is published by Anthology Editions