Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld has a long association with video games. Not only was the author himself a fan of Doom, Thief, and The Elder Scrolls, but the relationship between his satirical fantasy world and video games goes all the way back to 1986’s The Colour of Magic – a text-adventure adaptation of Pratchett’s first Discworld novel. Later games based on Pratchett’s work include 1995’s Discworld, a notoriously difficult adventure game voiced by actors including Eric Idle and Tony Robinson, and 1999’s Discworld Noir, a 3D detective game where you play as the universe’s first private investigator.

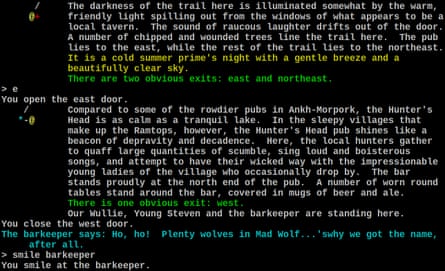

But the most ambitious Discworld game in existence is not officially associated with Terry Pratchett at all. The Discworld MUD is a text-based “multi-user-dungeon” – an early form of online role-playing game where everything from places to in-game actions are described in words. Created in 1991 by David “Pinkfish” Bennett, the MUD has been in consistent service for over 30 years, and today offers the most detailed depiction of the Discworld outside of Pratchett’s books. Not only does it feature most of the key locations, from the city of Ankh-Morpork to areas such as Klatch and the Ramtops, it has seven guilds, player-run shops, and countless quests and adventures featuring many of the Discworld’s most notable characters. It even has its own newspaper.

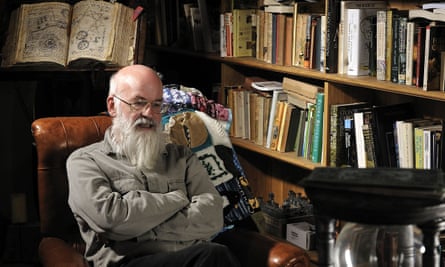

“I have a long, long history of falling into things by accident,” says Jacqui Greenland, one of the six administrators who oversee the MUD’s operations. Known in-game as Sojan, Greenland has been associated with the MUD for most of its history, first logging on while at university in November 1992. At the time, it was known as Discworld 3, one of several Discworld-themed MUDs in operation. Indeed, the first that Jacqui heard of it was when a friend told her: “Don’t bother with Pinkfish’s Discworld, because it’s crap.”

It’s true that back in 1992, it was was nothing like the vast and highly intricate game that it has become today. It was a small, unremarkable fantasy adventure that happened to be set in Ankh-Morpork. “It had nothing that made Discworld Discworld,” Greenland says. “It was fairly generic.”

But then, it received the grace of Terry Pratchett to continue development, after the author declared his awareness of these projects via a UseNet post. “He said ‘This is an offer, if you promise never to make a profit, and you write me an email, I’ll send you an email giving you permission’,” Greenland says. “David Bennett’s got that email somewhere.”

This permission acted as a catalyst that spurred on Discworld 3’s other unique attribute: a community that was as interested in creating quests, characters and storylines as it was in play. In her 30-year involvement with the MUD, Greenland only spent nine months as a player. “I had these ideas about what could be added, and in the end, someone just said ‘I can’t be bothered listening to you tell me what to do constantly, so I’m just going to promote you to creator so you can do it yourself.’”

Since the MUD’s creation in 1991, over 800 people have contributed to it as creators, writing new areas, character dialogues, quests, guilds, item descriptions, and much more. Today, it has over 12m lines of code. For context, the Witcher 3 – regarded as one of the best RPGs ever made – has between one and two million lines of code.

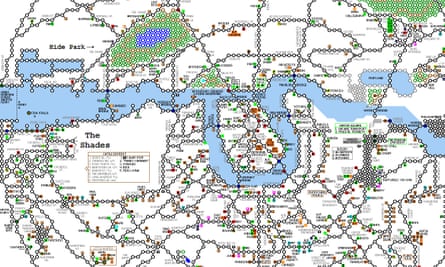

This isn’t the only indicator of the Discworld MUD’s scope. One of its veteran players, who goes by the username Quow, provides a quickfire tour. “There’s something like 20,000 individually crafted and detailed rooms, each with room objects and room chats, and then somewhere around 16m terrain rooms filling up much of the Disc between those places,” he says. “We have Djelibeybi and Ephebe in the Klatch deserts, Genua, well described from the Witches books, Bes Pelargic in Agatea, all the quaint little villages in and around Lancre and the Ramtops in general.”

Arguably more remarkable than the MUD’s size, however, is the detail in which players can read about and interact with the Discworld. “I remember what impressed me most about it to start with was the depth of the implementation,” says Kake, one of the MUD’s current creators, who joined in 2004. “If there was a street with a tree in it, you could look at the tree, which might tell you something about its branches, and then you could look at the branches, which might mention a bird’s nest, and then you could look at the nest, which might tell you it had eggs in it – however far you went down there was never an error message claiming that the thing you were trying to look at wasn’t there.”

It’s a level of detail that any fantasy game would be proud of. But the Discworld is no ordinary fantasy realm. Pratchett’s work blends satire, parody, allegory and sociopolitical commentary, all in a highly distinctive comedic tone. It would be a difficult style for any individual to replicate, let alone a loose collaboration of creatively minded gamers. So how do the MUD’s creators approach the tricky prospect of adapting Pratchett’s style?

The answer is that they don’t. At least, not specifically. While the MUD is set in Pratchett’s Discworld, it isn’t intended as a one-to-one adaptation of his work. The layout, for example, is based on officially published maps of the Discworld. But there’s also a lot of stuff that you won’t find in Pratchett’s Discworld. “Our focus these days is more on keeping the game fresh, interesting, fun, and well-balanced,” Kake points out, “using our own imaginations and ideas about what new things players will enjoy.”

Greenland states that the MUD’s approach to humour derives as much from the influence of David Bennett as it does Pratchett’s own writing. “The zany sense of humour, bizarre bits and pieces, that all came from David Bennett,” she says. Indeed, since Pratchett’s death in 2015 (and arguably for some time before that), the chief source of inspiration has been the community’s own interactions with the game they’ve built. The MUD is ultimately a role-playing game, and RPGs thrive on the overlap between play and creation.

Take the two in-game newspapers. One of these, the AM Daily, is edited by a player known simply as Jeanie. “The AM Daily is published once per month, and you can buy a copy of the current edition from newspaper boxes and characters, or subscribe and have it delivered each time a new edition is published,” she says.

The paper covers events that have happened in the game through the month, with stories ranging from game updates to guild activities and player-run events. It’s similar to a community blog that a developer would run for any modern game. But the fact it’s published inside the MUD by players themselves, means that stories often interweave with the game’s own fiction. “There was an excellent fictional serial story

that was set in the city of Ephebe as found on the MUD,” Jeanie says. “You could follow the steps of the story’s protagonist and find the artisan he met or the taverna he went to for a glass of wine.”

Perhaps the most enduring influence Pratchett’s work still holds over the MUD is the author’s progressive and inclusive outlook. For example, there is a relatively large proportion of blind players, so it has been updated multiple times to make it compatible with screen-readers. The creators also continually update some of the MUD’s older rooms, where humour or descriptions manifest as lazy stereotyping or punching down. “We’re not trying to make an exact copy of the books, but rather to create a world inspired by Pterry’s work,” Kake explains. “It’s clear from reading his books that he carried on learning and growing throughout his life, and I think we as creators can best continue his efforts working to eliminate racism, fatphobia, transphobia, and other prejudices from our game.”

It is not an online utopia. Like any online community, it encounters issues with harassment and abuse, and combating it requires an active stance. “Most of my input these days is being the boogeyman no one wants things escalated to,” Greenland says. I ask her how often such problems come up. “Not that frequently. But even once a year is too much for me.”

Players’ commitment to maintaining and updating the MUD is a big part of why it has remained active for so long, despite the huge advancement and proliferation of video games during that time. The community isn’t as large as it once was, and its founder David Bennett hasn’t been involved for over a decade. But you’ll still find the Discworld being explored by 50 to 100 players at any one time, and it is still being updated, with the day-to-day operation overseen by a new generation of administrators such as Aristophenes and Pit.

Greenland herself doesn’t play or create much these days. Instead, she keeps the lights on, running and maintaining the server on which the Discworld’s thousands of rooms, hundreds of player-characters, and millions of lines of code are housed. I asked her what’s kept her involved for all this time.

“I don’t know why I keep on doing it, why I keep having that passion,” she says. “I’ve literally spent a whole day of a holiday in a foreign country, remotely logging in to start bringing the server backup online, because it died. I have an attachment to the place that I developed at university 30 years ago, and it’s never left.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion