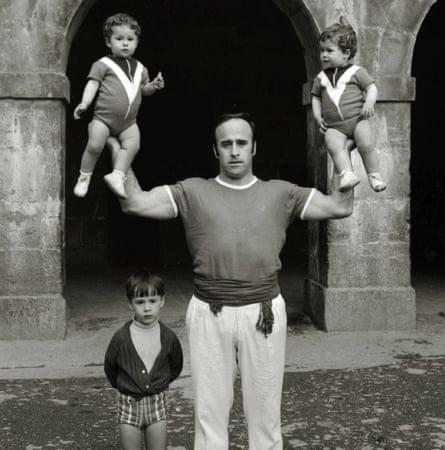

I came out twisted,” Julen Lopetegui says. His father, José Antonio, was a harrijasotzailea, a champion Basque stonelifter who competed under the name Aguerre II, held the record for raising 22 100-kilo cylinders in a minute and rejected proposals from a promoter linked to Al Capone to become a heavyweight boxer. His uncle Luis, Aguerre I, had been a harrijasotzailea too, known throughout the land. And his brother Joxean was a professional pelotari. But then something went wrong.

Julen could play Basque pelota too, a basket for a hand, the ball travelling faster than any sport on earth. “I had a chance to be professional but my passion was football,” he says. “I’m the black sheep of the family, hooked on football from the start. My dad was well known in an era when stonelifting was big, a living. My brother was a pelotari at a high level. But when I did the typical psychoanalyses, the ‘what will you be?’ tests at school, the first answer to come out was footballer. The second – get this – was football journalist. If I didn’t play, at least I could see games for free.”

If the world lost a byline, it gained a goalkeeper and eventually a coach, guided by lessons learned at home even if he chose the wrong sport. “My father was a great sportsman, an outstanding athlete, but he didn’t do football at all,” Lopetegui says. “Yet growing up with the values he instilled – effort, sacrifice, never seeking excuses – helped forge my character.” He came out twisted but turned out all right. When Joxean was pelota champion in 1986, Julen was joining Castilla from Real Sociedad’s academy – the start of a 17-year career that passed through Real Madrid and Barcelona and the 1994 World Cup.

Then came coaching, a transition towards a profession, a calling, he dissects with fascinating depth: the methods applied, the price exacted, the ideals. “I remember Luis Aragonés telling me: ‘Kid, listen, the first thing is: take off the shirt.’ What’s he talking about? Of course I’ve taken it off. But I hadn’t. It’s not the same, like looking at the same river from two banks. Sometimes it’s like giving a pill: you have to deliver it the right way.”

Lopetegui nearly went to Wolves and held the most high-pressure jobs in Spain: Madrid and the selección. On Thursday, his Sevilla team face West Ham in the Europa League.

Sevilla’s captain, Ivan Rakitic, asked to describe his coach, says: “When he gets home I’m sure he explains [tactics] to his wife and daughter.” Lopetegui protests: “If something football-related comes up, it’s not because I mention it but because they ask.” But then he adds, laughing: “I’m fortunate that for now my family accept me as I am.” Intense is one word for a man who can end games looking as exhausted as his players.

“You see yourself and sometimes you like what you see more than others,” he admits, “but the conclusion I’ve reached is I am what I am. There’s no escaping that coaching takes a lot out of you. You have to learn to live with that craziness; if not you die. You have to overcome the biggest obstacle, which is being able to take the pressure and take it off your players. Your passion and energy aren’t governed by age; you adapt, improve daily, change. That’s what enables you to keep going.”

There’s a pause, a smile: “For as long as they want you. When they don’t want you … ”

Can you actually enjoy it? “Like a little kid. Even the most difficult moments because that’s when a coach’s intervention has to be at its best. And the hard moments make the character.”

There have been plenty. After a 10-game spell at Rayo, Lopetegui started with youth football, leading Spain to European titles at Under-19 and Under-21 level, in 2012 and 2013 respectively. There is a fulfilment and fondness in seeing “his” kids succeed – David de Gea, Thiago Alcântara, Koke, Álvaro Morata and Dani Carvajal head a long list – but he sought something else. “You don’t have the same pressure. It’s not a ‘hard drug’; senior, elite football is the hard drug. My passion was always to coach at elite level.”

It doesn’t come much more elite, more pressured than this. Lopetegui was sacked from the Spain job on the eve of the 2018 World Cup, the RFEF president José Luis Rubiales reacting furiously to Real Madrid announcing him as their new manager. Forced to leave the training camp and return alone, there was something cruel and crushingly inevitable about his Bernabéu spell then not lasting long. The hurt, on the other hand, does.

“It’s something I feel far removed from now,” Lopetegui insists. “Everything could have been handled better. We played the best teams in the world, except Brazil: England in England, Italy in Italy, Belgium in Belgium, Germany in Germany, France in France. Argentina at home. And as well as being unbeaten, we built a clear identity. We were ready to achieve very, very big things and it hurt because they took us out at the moment when hope was highest. Many coaches have gone to a club after a World Cup or Euros: it could have been handled far more naturally. But the chapter’s closed.”

The best revenge is to live well, they say. “But I’d be a mediocre man if I took motivation from that, wanting to prove people wrong,” Lopetegui responds. “Motivation is inside you. You don’t face the day thinking: ‘Two years ago.’ Your passion drives you. That’s the good energy; the other kind, quite honestly, I really don’t like it. You learn from bad experiences but the energy that drives you is intrinsic not extrinsic. It’s hope I feed off, not the past.”

He has certainly lived well. If there was some reticence when Lopetegui arrived in Seville, a hangover from the Spain fallout, it is long gone. When they won the derby recently, he stood before fans, holding his heart as they chanted his name. In his first season he had returned them to the Champions League and won the Europa League. Last season, they reached week 36 in the title race. This season, there’s the Europa League again, the competition no one embraces like Sevilla and one Lopetegui insists “big teams really want to win; it has gained weight and prestige”. Sevilla are also the only side aspiring to catch Madrid.

The gap is eight points but they’re still fighting. It’s a miracle they’re even standing, the absentees in double figures most weeks. As he talks, the phone rings. It’s the sporting director, Monchi. “Maybe he’s ringing to say he’s signed Haaland,” Lopetegui laughs. “I’d just like 11 [fit players].” He glances at the whiteboard. “Some days we trained with eight or nine,” he says.

Respite came in the winter window, Sevilla standing firm as Newcastle courted Diego Carlos and signing Tecatito Corona and Anthony Martial. In the summer, they had resisted Chelsea’s £42m bid for Jules Koundé, ambition expressed.

“There were players who could have left but the offers didn’t meet the valuation. It’s important the players are then happy to continue. [Diego] is committed, there are no doubts … Anthony and Corona’s arrivals help us improve. We’re excited about Anthony. He can give us things others can’t: a very good player technically and physically, powerful and versatile, playing wide or centrally. He gives that touch of quality at the end of a move and makes us a bit more vertical. We’ll help him translate those qualities into performance as soon as possible.”

No point imagining a Seville derby in Sevilla’s stadium for the final? “You can imagine … but what happens in football is usually way beyond anything you imagined. There are a thousand examples.” And, besides, West Ham are first.

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned it’s that you can’t say: ‘This will happen.’ The future has twisted horns. All you can think about is today, and with the same enthusiasm as when you were a kid. The day I don’t feel that, I won’t be able to transmit it to my players: they have to feel the joy, the excitement. And there’s something magical about football: every day something happens you weren’t expecting. I walk in each morning and say: ‘What have we got today?’ Because there’s always something.”