“I’ve never escaped Watergate,” says John Dean, as once again he allows the years to melt away, the old faces to crowd in and the secret tapes to whirr in his mind. “There’s just no choice. I’m living in the bubble. It’s become a fact of life.”

America has never escaped Watergate either. The biggest political scandal of the 20th century, and the only one to cause a presidential resignation, has become a byword for lost innocence and lost faith in institutions. Along with the Vietnam war, it marked the end of an era in which a president’s words were met with automatic trust rather than default scepticism.

Such is the notoriety that the “-gate” suffix has been applied to dozens of controversies, from Sharpiegate (Donald Trump showing a map altered using a black marker pen) to Deflategate (allegations that Tom Brady’s New England Patriots used deflated footballs) to Partygate (British prime minister Boris Johnson’s social gatherings that flouted Covid-19 restrictions).

Today the luxury Watergate hotel’s phone number ends in 1972 – the year of the burglary – and callers are greeted by a message that begins: “There’s no need to break in,” as well as recordings of President Richard Nixon. This month’s 50th anniversary of the break-in is being marked by books, exhibitions, TV dramas and a four-part CNN documentary series, Watergate: Blueprint for a Scandal, narrated by Dean himself.

In it the man who helped bring Nixon down draws a direct line from the Watergate break-in on 17 June 1972 to the insurrection at the US Capitol on 6 January 2021, taking stock of a half century that has seen the media fragment, the Republican party embrace authoritarian tendencies and presidents become less accountable. Dean has never been more concerned about American democracy than he is now.

“I was never worried about the country and the government during Watergate but from the day Trump was nominated, I had a knot in my stomach and, until he left, I never got rid of it,” Dean, 83, tells the Guardian via Zoom from a Washington hotel. “He just discovered late in his presidency the enormous powers he does have as president. He wants them now. He knows he can hurt his enemies and help his friends.”

He adds: “Nixon, who was very bright and understood how the government operated and what the levers of power really are was somebody who also could experience shame and accepted the rule of law. When the supreme court ruled against him, that was it. I can’t imagine, in a similar situation, Trump complying with a court order from the supreme court saying turn over your tapes.”

Dean was working for the justice department when he was recruited to the Nixon White House. But he soon discovered that John Ehrlichman would remain the president’s top legal adviser. “As White House counsel, I got the title – I didn’t get the job,” Dean says wryly. “It was frankly too good a title at 31 years of age to pass up, although I knew I would be doing the grunt work.”

It also did not take Dean long to discover that the Nixon administration was doing things differently. It kept an enemies list. It had approved a September 1971 burglary of the office of the psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsberg, the defence analyst who leaked the secret history of the Vietnam war known as the Pentagon Papers.

Dean himself had to intervene to squash an outlandish plan to firebomb the Brookings Institution, a thinktank in Washington where classified documents leaked by Ellsberg were being stored. “I did not know that the president had authorised the Brookings operation but I thought it was insane, whoever had authorised it,” he says.

Dean was out of the country on the day of the Watergate break-in but instantly guessed who was behind it. Five men had been arrested in the bungled operation to bug and steal documents from the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex – a dirty tricks operation aimed at sinking would-be challengers to Nixon in that year’s presidential election.

At first the incident seemed comically inept and inconsequential but, when it emerged in court that the lead burglar, James McCord, had worked for the CIA, journalists such as Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post sprang into action. Gradually they and others would trace a complex web that connected operatives known as “the plumbers” to the Committee to Re-elect the President (Creep) to senior White House officials and, finally, to Nixon himself.

But it was not until after the president won re-election in November 1972 that Dean felt himself sucked into the cover-up, arranging hush money for the Watergate burglars. He recalls: “[White House aide Chuck] Colson brings a recording he’s made of Howard Hunt, who was one of the managers of the burglars, and Hunt wants to be paid and if he doesn’t get paid, people are going to start talking.

“I knew enough of the criminal law to know this is either extortion or bribery. Now, my reaction is kind of interesting. I had just gotten married and I said, ‘Holy cow, we’re in trouble!’ So I decided then I’ve got to make the cover-up work and that’s when I dove in with both feet. It was foolish.”

He adds: “It’s only later [in March 1973] when Hunt starts extorting me personally for money that I said the same thing’s going to happen to everybody – it’s going to follow us the rest of our lives. There’ll be no end to it and Nixon has got to get out in front of it and we all have got to stand up and account for the mistakes we’ve made.”

Dean went to see Nixon in an effort to convince him that the cover-up would destroy his presidency. In later testimony to Congress, Dean explained: “I began by telling the president that there was a cancer growing on the presidency and that if the cancer was not removed that the president himself would be killed by it.”

Dean has since been able to listen back to the conversation thanks to Nixon’s secret recording system at the White House. “The quality of the tapes in general is just awful but I’m sitting right over one of the little microphones that had been bored into the desk, so my voice is crystal clear. I can actually hear myself sigh at times, exasperated with the reaction I’m getting.

“I took him through every problem he had and, to my amazement, he had an answer for everything I thought was a problem. I can hear my frustration with this man and I’m waiting for his fist to come down on the desk.

“Finally, at the end, when it’s clear he is going to do nothing, I say, ‘Well, Mr President, people are going to go to jail for this.’ He says, ‘Like who?’ To bring it home, I say, ‘Like me!’ So he knows his White House counsel thinks he’s on his way to jail. I hope that will turn him but all it does is turn him against me because now I’m radioactive.”

What were Dean’s impressions of Nixon the man? “He wasn’t who I thought he was. He clearly wanted to engage in criminal behaviour and he would blame everybody but himself. What surprised me most is he spent a lot of time conspicuously trying to impress me.”

On one occasion, Dean recounts, Nixon told him that he was reading a book about President John’s F Kennedy’s ruthless streak. “I’ve often thought he did that to impress upon me that all presidents are ruthless to a degree because I’m the one who had blown up the the plan to firebomb the Brookings Institution. He knew that and he was worried, maybe, I thought presidents shouldn’t do things like that. He was trying to do a little tutorial on me.”

Wary that he would be turned into a scapegoat, Dean began cooperating with Senate investigators. At the end of April 1973, with the walls closing in, Nixon aides HR Haldeman and Ehrlichman resigned and Dean himself was forced out.

He then publicly turned against Nixon by testifying to the Senate Watergate committee – becoming the first White House official to accuse the president of being directly involved in the cover-up. The blockbuster hearing in June was watched by millions on television. But first Dean got a haircut.

“It was a barber I had never been to and it was last-minute. I had done an interview with Walter Cronkite and my hair was curling over my shoulders. I said that is just not a good look; I’d better get that neck cleaned up or my mother will be all over me. In the barbershop, he just put a bowl on my head and cut it so it was much shorter than people were used to: ‘Oh, he’s changing his image!’

“The same thing with the glasses. I had actually scratched my cornea. I had worn contacts during the Cronkite interview and noticed I was just blinking madly. I have never really worn contacts since I had that experience.”

Dean read from a mammoth prepared statement that took almost the entire first day. “If I had been told in advance I was going to have to read it all, it would not have been 60,000 words. It may have been 6,000 at max. But it’s much easier to write a long statement than it is a short one so I just let it flow. It took eight hours to read it.”

Later that year Dean pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice, was disbarred and served four months; he was in the witness protection programme so never went to prison. Meanwhile Alexander Butterfield, Nixon’s deputy chief of staff, had testified that there was a recording system in the White House.

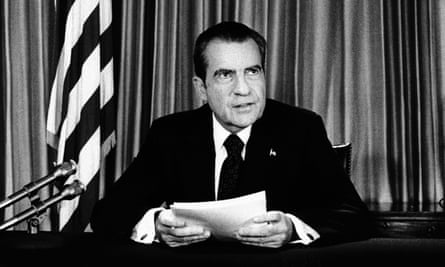

The supreme court ordered the release of a “smoking gun tape” confirming Dean’s claim that Nixon told aides to order the CIA to shut down the FBI investigation into the burglary. Nixon lost the confidence of fellow Republicans and, facing impeachment, resigned in August 1974. The president gave a final victory sign on the South Lawn before a helicopter spirited him away.

Dean, who happened to have his molars removed that day, cannot recall any particular emotion. “I didn’t feel vindication or anything of that nature. We’d been at battle. It’s very lucky that the system worked as it was designed.”

He continues: “It’s very hard to look at Watergate without looking through the lens of Trump where it didn’t work, or hasn’t yet. It’s not over. If Trump gets through with zero accountability, then the system is deeply flawed and a lot of that is probably traceable to the Ford pardon.”

When President Gerald Ford granted Nixon a full pardon in September 1974, Bernstein exclaimed to Woodward: “You’re not gonna believe it. The son of a bitch pardoned the son of a bitch!” (Woodward has more recently praised Ford’s act as one of courage.) Dean’s initial reaction was different.

“At the time I thought it was right and it was understandable because I knew he couldn’t govern with Watergate hanging over him. Every day would be a new decision as to what he does and doesn’t turn over from the Nixon archive.

“It would have consumed his presidency but so I understood it, but in the long run it codified the memo that was prepared then re-prepared during the Clinton presidency, that a sitting president can’t be indicted. Well, a post-president can’t be indicted when he’s pardoned.”

Dean went into business for a while and tried to leave Watergate behind but a 1991 book that alleged he and his wife, Maureen, masterminded the cover-up prompted him to take legal action. This led to years of research, immersing himself in the tapes and making peace with the subject. He has written several books, including two about Watergate, and teaches a Watergate-related course for lawyers.

He has also been called upon by the media and Congress to provide expert analysis during scandals in the Clinton and Trump administrations. Now a grandfather living in Beverly Hills, California, he quips: “My speciality, I guess, is presidents in deep trouble.”

But if something like Watergate happened in the 2020s, he does not believe it would necessarily bring down a president again. “It would be very different today, primarily because of Fox News, which would be mounting a fulsome defence of him. We are far more polarised today than we were. We were polarised during Watergate but not to the degree we are today.”

Dean will be watching this week’s January 6 hearings on Capitol Hill intently but reckons that Republicans, at least, face less accountability than they once did. “Trump is a poster boy for authoritarianism and the authoritarian followers just fell in line. They just absolutely did what authoritarian followers do: click their heels, salute, ‘Yes sir!’”

That leaves him fearing for the future of American democracy. “Not so much Trump but now the whole Republican party has shifted into this authoritarian stance. Not all the Republicans I know are that way but too many of them now think authoritarianism is just dandy because it works, it’s efficient. Well, Mussolini ran the trains on time, didn’t he – but at some expense.”