In 1885, John D. Rockefeller wrote one of his partners, “Let the good work go on. We must ever remember we are refining oil for the poor man and he must have it cheap and good.” Or as he put it to another partner: “Hope we can continue to hold out with the best illuminator in the world at the lowest price.”

Even after 20 years in the oil business, “the best … at the lowest price” was still Rockefeller’s goal; his Standard Oil Company had already captured 90 percent of America’s oil refining and had pushed the price down from 58 cents to eight cents a gallon. His well-groomed horses delivered blue barrels of oil throughout America’s cities and were already symbols of excellence and efficiency. Consumers were not only choosing Standard Oil over that of his competitors; they were also preferring it to coal oil, whale oil, and electricity. Millions of Americans illuminated their homes with Standard Oil for one cent per hour; in doing so, they made Rockefeller the wealthiest man in American history.

Rockefeller’s early life hardly seemed the making of a near billionaire. His father was a peddler who often struggled to make ends meet. His mother stayed at home to raise their six children. They moved around upstate New York—from Richford to Moravia to Oswego—and eventually settled in Cleveland, Ohio. John D. was the oldest son. Although he didn’t have new suits or a fashionable home, his family life was stable. From his father he learned how to earn money and hold on to it; from his mother he learned to put God first in his life, to be honest, and to help others.

“From the beginning,” Rockefeller said, “I was trained to work, to save, and to give.” He did all three of these things shortly after he graduated from the Cleveland public high school. He always remembered the “momentous day” in 1855, when he began work at age sixteen as an assistant bookkeeper for 50 cents per day.

On the job, Rockefeller had a fixation for honest business. He later said, “I had learned the underlying principles of business as well as many men acquire them by the time they are forty.” His first partner, Maurice Clark, said that Rockefeller “was methodical to an extreme, careful as to details and exacting to a fraction. If there was a cent due us he wanted it. If there was a cent due a customer he wanted the customer to have it.” Such precision irritated some debtors, but it won him the confidence of many Cleveland businessmen; at age nineteen, Rockefeller went into the grain shipping business on Lake Erie and soon began dealing in thousands of dollars.

Rockefeller so enjoyed business that he dreamed about it at night. Where he really felt at ease, though, was with his family and at church. His wife, Laura, was also a strong Christian, and they spent many hours a week attending church services, picnics, or socials at the Erie Street Baptist Church. Rockefeller saw a strong spiritual life as crucial to an effective business life. He tithed from his first paycheck and gave to his church, a foreign mission, and the poor. He sought Christians as business partners and later as employees. One of his fellow churchmen, Samuel Andrews, was investing in oil refining; and this new frontier appealed to young John. He joined forces with Andrews in 1865 and would apply his same precision and honesty to the booming oil industry.

Discovering Crude Oil

The discovery of large quantities of crude oil in northwest Pennsylvania soon changed the lives of millions of Americans. For centuries, people had known of the existence of crude oil scattered about America and the world. They just didn’t know what to do with it. Farmers thought it a nuisance and tried to plow around it; others bottled it and sold it as medicine.

In 1855, Benjamin Silliman, Jr., a professor of chemistry at Yale, analyzed a batch of crude oil. After distilling and purifying it, he found that it yielded kerosene—a better illuminant than the popular whale oil. Other by-products of distilling included lubricating oil, gasoline, and paraffin, which made excellent candles. The only problem was cost: it was too expensive to haul the small deposits of crude from northwest Pennsylvania to markets elsewhere.

Silliman and others, however, formed an oil company and sent “Colonel” Edwin L. Drake, a jovial railroad conductor, to Titusville to drill for oil. “Nonsense,” said local skeptics. “You can’t pump oil out of the ground as you pump water.” Drake had faith that he could; in 1859, when he built a 30-foot derrick and drilled 70 feet into the ground, all the locals scoffed. When he hit oil, however, they quickly converted and preached oil drilling as the salvation of the region.

There were few barriers to entering the oil business: drilling equipment cost less than $1,000, and oil land seemed abundant. By the early 1860s, speculators were swarming northwest Pennsylvania, cluttering it with derricks, pipes, tanks, and barrels. “Good news for whales,” concluded one newspaper. America had become hooked on kerosene.

Cleveland was a mere hundred miles from the oil region, and Rockefeller was fascinated with the prospects of refining oil into kerosene. He may have visited the region as early as 1862. By 1863, he was talking oil with Samuel Andrews, and two years later they built a refinery together. Two things about the oil industry, however, bothered Rockefeller right from the start: the appalling waste and the fluctuating prices.

The overproducing of oil and the developing of new markets caused the price of oil to fluctuate wildly. In 1862, a barrel (42 gallons) of oil dropped in value from $4.00 to 35 cents. Later, when President Lincoln bought oil to fight the Civil War, the price jumped back to $4.00, then to $13.75. A blacksmith took $200 worth of drilling equipment and drilled a well worth $100,000. Others, with better drills and richer holes, dug four wells worth $200,000. Alongside the new millionaires of the moment were the thousands of fortune hunters who came from all over to lease land and kick down shafts into it with cheap foot drills. Most failed. Even Colonel Drake died in poverty. As J.W. Trowbridge wrote, “Almost everybody you meet has been suddenly enriched or suddenly ruined (perhaps both within a short space of time), or knows plenty of people who have.”

Those few who struck oil often wasted more than they sold. Thousands of barrels of oil poured into Oil Creek, not into tanks. Local creek bottoms were often flooded with runaway oil; the Allegheny River smelled of oil and glistened with it for many miles toward Pittsburgh. Gushers of wasted oil were bad enough; sometimes a careless smoker would turn a spouting well into a killing inferno. Other wasters would torpedo holes with nitroglycerine, sometimes losing the oil and their lives.

Rockefeller was intrigued with the future of the oil industry but was repelled by its past. He shunned the drills and derricks and chose the refining end instead. Refining eventually became very costly, but in the 1860s, the main supplies were only barrels, a trough, a tank, and a still in which to boil the oil. The yield would usually be about 60 percent kerosene, 10 percent gasoline, 5 to 10 percent benzol or naphtha, with the rest being tar and wastes.

High prices and dreams of quick riches brought many into refining, and this attracted Rockefeller, too. But right from the start, he believed that the path to success was to cut waste and produce the best product at the lowest price. Sam Andrews, his partner, worked on getting more kerosene per barrel of crude. Both men searched for uses for the byproducts: they used the gasoline for fuel, some of the tars for paving, and shipped the naphtha to gas plants. They also sold lubricating oil, vaseline, and paraffin for making candles. Other Cleveland refiners, by contrast, were wasteful: they dumped their gasoline into the Cuyahoga River, they threw out other byproducts, and they spilled oil throughout the city.

In Search of Ways to Save

Rockefeller was constantly looking for ways to save. For example, he built his refineries well and bought no insurance. He also employed his own plumber and almost halved the cost of labor, pipes, and plumbing materials. Coopers charged $2.50 per barrel; Rockefeller cut this to $.96 when he bought his own tracts of white oak timber, his own kilns to dry the wood, and his own wagons and horses to haul it to Cleveland. There, with machines, he made the barrels, then hooped them, glued them, and painted them blue. Rockefeller and Andrews soon became the largest refiners in Cleveland. In 1870, they reorganized with Rockefeller’s brother William, and Henry Flagler, the son of a Presbyterian minister. They renamed their enterprise Standard Oil.

Under Rockefeller’s leadership, they plowed the profits into bigger and better equipment. As their volume increased, they hired chemists and developed 300 by-products from each barrel of oil. These ranged from paint and varnish to dozens of lubricating oils to anesthetics. As for the main product, kerosene, Rockefeller made it so cheaply that whale oil, coal oil, and, for a while, electricity lost out in the race to light American homes, factories, and streets. “We had vision,” Rockefeller later said. “We saw the vast possibilities of the oil industry, stood at the center of it, and brought our knowledge and imagination and business experience to bear in a dozen, in twenty, in thirty directions.”

Another area of savings came from rebates from railroads. The major eastern railroads—the New York Central, the Erie, and the Pennsylvania—all wanted to ship oil and were willing to give discounts, or rebates, to large shippers. These rebates were customary and dated back to the first shipments of oil. As the largest oil refiner in America, Rockefeller was in a good position to save money for himself and for the railroad as well. He promised to ship 60 carloads of oil daily and provide all the loading and unloading services. All the railroads had to do was to ship it east. Commodore Vanderbilt of the New York Central was delighted to give Rockefeller the largest rebate he gave any shipper for the chance to have the most regular, quick, and efficient deliveries. When smaller oil men screamed about rate discrimination, Vanderbilt’s spokesmen gladly promised the same rebate to anyone else who would give him the same volume of business. Since no other refiner was as efficient as Rockefeller, no one else got Standard Oil’s discount.

Many of Rockefeller’s competitors condemned him for receiving such large rebates. But Rockefeller never would have gotten them had he not been the largest shipper of oil. These rebates, on top of his remarkable efficiency, meant that most refiners could not compete. From 1865 to 1870, the price of kerosene dropped from 58 to 26 cents per gallon.

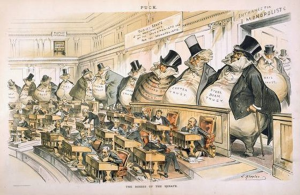

Rockefeller made profits during every one of these years, but most of Cleveland’s refiners disappeared. Naturally, there were hard feelings. Henry Demarest Lloyd, whose cousin was an unhappy oil man, wrote Wealth Against Commonwealth in 1894 to denounce Rockefeller. Ida Tarbell, whose father was a Pennsylvania oil producer, attacked Rockefeller in a series of articles for McClure’s magazine.

A Boon for Consumers

Some of the oil producers were unhappy, but American consumers were pleased that Rockefeller was selling cheap oil. Before 1870, only the rich could afford whale oil and candles. The rest had to go to bed early to save money. By the 1870s, with the drop in the price of kerosene, middle- and working-class people all over the nation could afford the one cent an hour that it cost to light their homes at night. Working and reading became after-dark activities new to most Americans in the 1870s.

Rockefeller quickly learned that he couldn’t please everyone by making cheap oil. He pleased no one, though, when he briefly turned to political entrepreneurship in 1872. He joined a pool called the South Improvement Company and it turned out to be one of the biggest mistakes in his life.

The scheme was hatched by Tom Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Scott was nervous about low oil prices and falling railroad rates. He thought that if the large refiners and railroads got together they could artificially fix high prices for themselves. Rockefeller decided to join because he would get not only large rebates but also drawbacks, which were discounts on that oil which his competitors, not he, shipped. The small producers and refiners bitterly attacked Rockefeller and forced the Pennsylvania Legislature to revoke the charter of the South Improvement Company. No oil was ever shipped under this pool, but Rockefeller got bad publicity from it and later admitted that he had been wrong.

At first, the idea of a pool appealed to Rockefeller because it might stop the glut, the waste, the inefficiency, and the fluctuating prices of oil. The South Improvement Company showed him that this would not work, so he turned to market entrepreneurship instead. He decided to become the biggest and best refiner in the world. First, he put his chemists to work trying to extract even more from each barrel of crude. More important, he tried to integrate Standard Oil vertically and horizontally by getting dozens of other refiners to join him. Rockefeller bought their plants and talent; he gave the owners cash or stock in Standard Oil.

From Rockefeller’s standpoint, a few large vertically integrated oil companies could survive and prosper, but dozens of smaller companies could not. Improve or perish was Rockefeller’s approach. “We will take your burden,” Rockefeller said. “We will utilize your ability; we will give you representation; we will all unite together and build a substantial structure on the basis of cooperation.” Many oil men rejected Rockefeller’s offer, but dozens of others all over America sold out to Standard Oil.

When they did, Rockefeller simply shut down the inefficient companies and used what he needed from the good ones. Officers Oliver Payne, H.H. Rogers, and President John Archbold came to Standard Oil from these merged firms.

Buying out competitors was a tricky business. Rockefeller’s approach was to pay what the property was worth at the time he bought it. Outmoded equipment was worth little, but good personnel and even good will were worth a lot. Rockefeller had a tendency to be generous because he wanted the future good will of his new partners and employees. “He treated everybody fairly,” concluded one oil man. “When we sold out he gave us a fair price. Some refiners tried to impose on him and when they found they could not do it, they abused him. I remember one man whose refinery was worth $6,000, or at most $8,000. His friends told him, ‘Mr. Rockefeller ought to give you $100,000 for that.’ Of course Mr. Rockefeller refused to pay more than the refinery was worth, and the man … abused Mr. Rockefeller.”

Cutting Costs

Bigness was not Rockefeller’s real goal. It was just a means of cutting costs. During the 1870s, the price of kerosene dropped from 26 to eight cents a gallon, and Rockefeller captured about 90 percent of the American market. This percentage remained steady for years. Rockefeller never wanted to oust all of his rivals, just the ones who were wasteful and those who tarnished the whole trade by selling defective oil. “Competitors we must have, we must have,” said Rockefeller’s partner Charles Pratt. “If we absorb them, be sure it will bring up another.”

Just as Rockefeller reached the top, many predicted his demise. During the early 1880s, the entire oil industry was in jeopardy. The Pennsylvania oil fields were running dry and electricity was beginning to compete with lamps for lighting homes. No one knew about the oil fields out West, and few suspected that the gasoline engine would be the power source of the future. Meanwhile, the Russians had begun drilling and selling their abundant oil, and they raced to capture Standard Oil’s foreign markets. Some experts predicted the imminent death of the American oil industry; even Standard Oil’s loyal officers began selling some of their stock.

Rockefeller’s solution to these problems was to stake the future of his company on new oil discoveries near Lima, Ohio. Drillers found oil in this Ohio-Indiana region in 1885, but they could not market it. It had a sulfur base and stank like rotten eggs. Even touching this oil meant a long, soapy bath or social ostracism. No one wanted to sell or buy it, and no city even wanted it shipped there. Only Rockefeller seemed interested in it. According to Joseph Seep, chief oil buyer for Standard Oil:

Mr. Rockefeller went on buying leases in the Lima field in spite of the coolness of the rest of the directors, until he had accumulated more than 40 million barrels of that sulfurous oil in tanks. He must have invested millions of dollars in buying and storing and holding the sour oil for two years, when everyone else thought that it was no good.

Rockefeller had hired two chemists, Herman Frasch and William Burton, to figure out how to purify the oil; he counted on them to make it usable. Rockefeller’s partners were skeptical, however, and sought to stanch the flood of money invested in tanks, pipelines, and land in the Lima area. They “held up their hands in holy horror” at Rockefeller’s gamble and even outvoted him at a meeting of Standard’s Board of Directors. “Very well, gentlemen,” said Rockefeller. “At my own personal risk, I will put up the money to care for this product: $2 million – $3 million, if necessary.” Rockefeller told what then happened:

This ended the discussion, and we carried the Board with us and we continued to use the funds of the company in what was regarded as a very hazardous investment of money. But we persevered, and two or three of our practical men stood firmly with me and constantly occupied themselves with the chemists until at last, after millions of dollars had been expended in the tankage and buying the oil and constructing the pipelines and tank cars to draw it away to the markets where we could sell it for fuel, one of our German chemists cried “Eureka!” We … at last found ourselves able to clarify the oil.

The “worthless” Lima oil that Rockefeller had stockpiled suddenly became valuable; Standard Oil would be able to supply cheap kerosene for years to come. Rockefeller’s exploit had come none too soon: the Russians struck oil at Baku, four square miles of the deepest and richest oil land in the world. They hired European experts to help Russia conquer the oil markets of the world. In 1882, the year before Baku oil was first exported, America refined 85 percent of the world’s oil; six years later this dropped to 53 percent. Since most of Standard’s oil was exported, and since Standard accounted for 90 percent of America’s exported oil, the Baku threat had to be met.

The Baku Threat

At first glance, Standard Oil seemed certain to lose. First, the Baku oil was centralized in one small area: this made it economical to drill, refine, and ship from a single location. Second, the Baku oil was more plentiful: its average yield was over 280 barrels per well per day, compared with 4.5 barrels per day from American wells. Third, Baku oil was highly viscous: it made a better lubricant (though not necessarily a better illuminant) than oil in Pennsylvania or Ohio. Fourth, Russia was closer to European and Asian markets. Standard Oil had to bear the costs of building huge tankers and crossing the ocean with them. One independent expert estimated that Russia’s costs of oil exporting were one-third to one-half of those of the United States. Finally, Russia and other countries slapped high protective tariffs on American oil; this allowed inefficient foreign drillers to compete with Standard Oil. The Austro-Hungarian empire, for example, imported over half a million barrels of American oil in 1882; but, by 1890 they were buying none. What was worse, local refiners there marketed a low-grade oil in barrels labeled “Standard Oil Company.” This allowed the Austro-Hungarians to dump their cheap oil and damage Standard’s reputation at the same time.

Rockefeller pulled out all stops to meet the Russian challenge. No small refinery would have had a chance; even a large vertically integrated company like Standard Oil was at a great disadvantage. Rockefeller never lost his vision, though, of conquering the oil markets of the world. First, he relied on his research team to help him out. William Burton, who helped clarify the Lima oil, invented “cracking,” a method of heating oil to higher temperatures to get more use of the product out of each barrel. Engineers at Standard Oil helped by perfecting large steamship tankers, which cut down on the costs of shipping oil overseas.

Second, Rockefeller made Standard Oil even more efficient. He used less iron in making barrel hoops and less solder in sealing oil cans. In a classic move, he used the waste (culm) from coal heaps to fuel his refineries; even the sweepings from his factory he sorted through for tin shavings and solder drops.

Third, Rockefeller studied the foreign markets and learned how to beat the Russians in their part of the world. He sent Standard agents into dozens of countries to figure out how to sell oil up the Hwang Ho River in China, along the North Road in India, to the east coast of Sumatra, and to the huts of tribal chieftains in Malaya. He even used spies, often foreign diplomats, to help him sell oil and tell him what the Russians were doing. He used different strategies in different areas. Europeans, for example, wanted to buy kerosene only in small quantities, so Rockefeller supplied tank wagons to sell them oil street by street. As Allan Nevins notes:

The [foreign] stations were kept in the same beautiful order as in the United States. Everywhere the steel storage tanks, as in America, were protected from fire by proper spacing and excellent fire- fighting apparatus. Everywhere the familiar blue barrels were of the best quality. Everywhere a meticulous neatness was evident. Pumps, buckets, and tools were all clean and under constant inspection, no litter being tolerated … The oil itself was of the best quality. Nothing was left undone, in accordance with Rockefeller’s long-standing policy, to make the Standard products and Standard ministrations, abroad as at home, attractive to the customer.

Rockefeller’s focus on quality meant that, in an evenly balanced price war with Russia, Standard Oil would win.

The Russian-American oil war was hotly contested for almost 30 years after 1885. In most markets, Standard’s known reliability would prevail, if it could just get its price close to that of the Russians. In some years, this meant that Rockefeller had to sell oil for 5.2 cents a gallon—leaving almost no profit margin—if he hoped to win the world. This he did; and Standard often captured two-thirds of the world’s oil trade from 1882 to 1891 and a somewhat smaller portion in the decade after this.

Rockefeller and his partners always knew that their victory was a narrow triumph of efficiency over superior natural advantages. “If,” as John Archbold said in 1899, “there had been as prompt and energetic action on the part of the Russian oil industry as was taken by the Standard Oil Company, the Russians would have dominated many of the world markets.”

At one level, Standard’s ability to sell oil at close to a nickel a gallon meant hundreds of thousands of jobs for Americans in general and Standard Oil in particular. Rockefeller’s margin of victory in this competition was always narrow. Even a rise of one cent a gallon would have cost Rockefeller much of his foreign market. A rise of three cents a gallon would have cost Rockefeller his American markets as well.

At another level, oil at little more than a nickel a gallon opened new possibilities for people around the world. William H. Libby, Standard’s foreign agent, saw this change and marveled at it. To the governor general of India he said:

I may claim for petroleum that it is something of a civilizer, as promoting among the poorest classes of these countries a host of evening occupations, industrial, educational, and recreative, not feasible prior to its introduction; and if it has brought a fair reward to the capital ventured in its development, it has also carried more cheap comfort into more poor homes than almost any discovery of modern times.

In Standard Oil, Rockefeller arguably built the most successful business in American history. In running it, he showed the precision of a bookkeeper and the imagination of an entrepreneur. Yet, in day-to-day operations, he led quietly and inspired loyalty by example. Rockefeller displayed none of the tantrums of a Vanderbilt or a Hill, and none of the flamboyance of a Schwab. At board meetings, he would sit and patiently listen to all arguments. He would often say nothing until the end. But his fellow directors all testified to his genius for sorting out the relevant details and pushing the right decision, even when it was shockingly bold and unpopular. “You ask me what makes Rockefeller the unquestioned leader in our group,” said John Archbold, later a president of Standard Oil. “Well, it is simple. In business we all try to look ahead as far as possible. Some of us think we are pretty able. But Rockefeller always sees a little further ahead than any of us—and then he sees around the comer.”

Some of these peeks around the corner helped Rockefeller pick the right people for the right jobs. He had to delegate a great deal of responsibility, and he always gave credit—and sometimes large bonuses—for work well done. Paying higher than market wages was Rockefeller’s controversial policy: he believed it helped slash costs in the long run. For example, Standard was rarely hurt by strikes or labor unrest. Also, he could recruit and keep the top talent and command their future loyalty.

“The Standard Oil Family”

Rockefeller approached the ideal of the “Standard Oil family” and tried to get each member to work for the good of the whole. As Thomas Wheeler said, “He managed somehow to get everybody interested in saving, in cutting out a detail here and there.” He sometimes joined the men in their work and urged them on. At 6:30 in the morning, there was Rockefeller “rolling barrels, piling hoops, and wheeling out shavings.” In the oil fields, there was Rockefeller trying to fit nine barrels on a eight-barrel wagon. He came to know the oil business inside-out and won the respect of his workers.

Praise he would give; rebukes he would avoid. “Very well kept—very indeed,” said Rockefeller to an accountant about his books before pointing out a minor error and leaving. One time, a new accountant moved into a room where Rockefeller kept an exercise machine. Not knowing what Rockefeller looked like, the accountant saw him and ordered him to remove it. “All right,” said Rockefeller, and he politely took it away. Later, when the embarrassed accountant found out whom he had chided, he expected to be fired; but Rockefeller never mentioned it.

Rockefeller treated his top managers as conquering heroes and gave them praise, rest, and comfort. He knew that good ideas were almost priceless: they were the foundation for the future of Standard Oil. To one of his oil buyers, Rockefeller wrote, “I trust you will not worry about the business. Your health is more important to you and to us than the business.” Long vacations at full pay were Rockefeller’s antidotes for his weary leaders. After Johnson N. Camden consolidated the West Virginia and Maryland refineries for Standard Oil, Rockefeller said, “Please feel at perfect liberty to break away three, six, nine, twelve, fifteen months, more or less. … Your salary will not cease, however long you decide to remain away from business.”

But neither Camden nor the others rested long. They were too anxious to succeed in what they were doing and to please the leader who trusted them so. Thomas Wheeler, an oil buyer for Rockefeller said, “I have never heard of his equal in getting together a lot of the very best men in one team and inspiring each man to do his best for the enterprise.”

Praise from Others

Not just Rockefeller’s managers, but his fellow entrepreneurs thought he was remarkable. In 1873, the prescient Commodore Vanderbilt said, “That Rockefeller! He will be the richest man in the country.” Twenty years later, Charles Schwab learned of Rockefeller’s versatility when Rockefeller invested almost $40 million in the controversial ore of the Mesabi iron range near the Great Lakes. Schwab said, “Our experts in the Carnegie Company did not believe in the Mesabi ore fields. They thought the ore was poor. … They ridiculed Rockefeller’s investments in the Mesabi.” But by 1901, Carnegie, Schwab, and J.P. Morgan had changed their minds and offered Rockefeller almost $90 million for his ore investments.

That Rockefeller was a genius is widely admitted. What is puzzling is his philosophy of life. He was a practicing Christian and believed in doing what the Bible said to do. Therefore, he organized his life in the following way: he put God first, his family second, and career third. This is the puzzle: how could someone put his career third and wind up with $900 million, which made him the wealthiest man in American history. This is not something that can be easily explained (at least not by conventional historical methods), but it can be studied.

“Spiritual Food”

Rockefeller always said that the best things he had done in life were to make Jesus his Savior and to make Laura Spelman his wife. He prayed daily first thing in the morning and went to church for prayer meetings with his family at least twice a week. He often said he felt most at home in church and in regular need of “spiritual food;” he and his wife also taught Bible classes and had ministers and evangelists regularly in their home.

Going to church, of course, is not necessarily a sign of a practicing Christian. Ivan the Terrible regularly prayed and went to church before and after torturing and killing his fellow men. Even Commodore Vanderbilt sang hymns out of one side of his mouth and out of the other spewed a stream of obscenities.

Rockefeller, by contrast, read the Bible and tried to practice its teachings in his everyday life. Therefore, he tithed, rested on the Sabbath, and gave valuable time to his family. This made his life hard to understand for his fellow businessmen. But it explains why he sometimes gave tens of thousands of dollars to Christian groups, while at the same time, he was trying to borrow over a million dollars to expand his business. It explains why he rested on Sunday, even as the Russians were mobilizing to knock him out of European markets. It explains why he calmly rocked his daughter to sleep at night, even though oil prices may have dropped to an all-time low that day.

Others panicked, but Rockefeller believed that God would pull him through if only he would follow His commandments. He worked to the best of his ability, then turned his problems over to God and tried not to worry. This is what he often said:

Early I learned to work and to play.

I dropped the worry on the way.

God was good to me every day.

Those who heard him say this may have thought he was mouthing platitudes, but the key to understanding Rockefeller is to recognize that he said it because he believed it.

When the Russians sold their oil in Standard’s blue barrels, Rockefeller did not get into strife. He knew that the book of James said, “For where envying and strife is, there is confusion and every evil work.” He fought the Russians, using his spies and his authority to stop them and outsell them; but he never slandered them or threatened them. No matter what, Rockefeller never lost his temper, either. This was one of the remarkable findings of Allan Nevins in his meticulous research on Rockefeller. During the 1930s, Nevins interviewed dozens of people who worked with Rockefeller and knew him intimately. Not one—son, daughter, friend, or foe—could ever recall Rockefeller losing his temper or even being perturbed. He was always calm.

The most famous example is the time Judge K.M. Landis fined Standard Oil of Indiana over $29 million. The charge was taking rebates; and Landis, an advocate of government intervention, publicly read the verdict of “guilty” for Standard Oil. Railway World was shocked that “Standard Oil Company of Indiana was fined an amount equal to seven or eight times the value of its entire property because its traffic department did not verify the statement of the Alton rate clerk that the six-cent commodity rate on oil had been properly filed with the Interstate Commerce Commission.” The New York Times called this decision a bad law and “a manifestation of that spirit of vindictive savagery toward corporations.” But Rockefeller, who had testified at the trial, was unruffled.

On the day of the verdict, he chose to play golf with friends. In the middle of their game, a frantic messenger came running through the fairways to deliver the bad news to Rockefeller. He calmly looked at the telegram, put it away, and said, “Well, shall we go on, gentlemen?” Then he hit his ball a convincing 160 yards. At the next hole, someone sheepishly asked Rockefeller, “How much is it?” Rockefeller said, “Twenty-nine million two hundred forty thousand dollars,” and added, “the maximum penalty, I believe. Will you gentlemen drive?” He ended the nine holes with a respectable score of 53, as though he hadn’t a care in the world.

Landis’s decision was eventually overruled, but Rockefeller was not so lucky in his fight against the Sherman Antitrust Act. Rockefeller had set up a trust system at Standard Oil merely to allow his many oil businesses in different states to be headed by the same board of directors. Some states, like Pennsylvania, had laws permitting it to tax all of the property of any corporation located within state borders. Under these conditions, Rockefeller found it convenient to establish separate Standard Oil corporations in many different states, but have them directed in harmony, or in trust, by the same group of men. The Supreme Court struck this system down in 1911 and forced Standard Oil to break up into separate state companies with separate boards of directors.

This decision was puzzling to Rockefeller and his supporters. The Sherman Act was supposed to prevent monopolies and those companies “in restraint of trade.” Yet Standard Oil had no monopoly and certainly was not restraining trade. The Russians, with the help of their government, had been gaining ground on Standard in the international oil trade. In America, competition in the oil industry was more intense than ever. Over 100 oil companies—from Gulf Oil in Texas to Associated Oil in California—competed with Standard. Standard’s share of the United States and world markets had been steadily declining from 1900 to 1910. Rockefeller, however, took the decision calmly and promised to obey it.

Even more remarkable than Rockefeller’s serenity was his diligence in tithing. From the time of his first job, where he earned 50 cents a day, the 16-year-old Rockefeller gave to his local Baptist church, to missions in New York City and abroad, and to the poor—black or white. As his salary increased, so did his giving. By the time he was 45, he was up to $100,000 per year; at age 53, he topped the $1,000,000 mark in his annual giving. His eightieth year was his most generous: $138,000,000 he happily gave away.

The more he earned the more he gave, and the more he gave the more he earned. To Rockefeller, it was the true fulfillment of the Biblical law: “Give, and it shall be given unto you; good measure, pressed down, and shaken together, and running over, shall men give into your bosom.” Not “money” itself but “the love of money” was “the root of all evil.” And Rockefeller loved God much more than his money. He learned what the prophet Malachi meant when he said, “Bring the whole tithe into the storehouse … and see if I will not throw open the floodgates of heaven and pour out so much blessing that you will not have room enough for it.” He learned what Jesus meant when he said, “With the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” So when Rockefeller proclaimed: “God gave me my money,” he did so in humility and in awe of the way he believed God worked.

Some historians haven’t liked the way Rockefeller made his money, but few have quibbled with the way he spent it. Before he died, he had given away about $550,000,000, more than any other American before him had ever possessed. It wasn’t so much the amount that he gave as it was the amazing results that his giving produced. At one level, he built schools and churches and supported evangelists and missionaries all over the world. After all, Jesus said, “Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature.”

Healing the sick and feeding the poor was also part of Rockefeller’s Christian mission. Not state aid, but Rockefeller philanthropy, paid teams of scientists who found cures for yellow fever, meningitis, and hookworm. The boll weevil was also a Rockefeller target, and the aid he gave in fighting it improved fanning throughout the South.

Seeking Solutions to Social and Medical Problems

Rockefeller attacked social and medical problems the same way he competed against the Russians—with efficiency and innovation. To get both of these, Rockefeller gave scores of millions of dollars to higher education. The University of Chicago alone got over $35,000,000. Black schools, Southern schools, and Baptist schools also reaped what Rockefeller had sown. His guide for giving was a variation of the Biblical principle—“If any would not work, neither should he eat.” Those schools, cities, or scientists who weren’t anxious to produce or improve didn’t get Rockefeller money. Those who did and showed results got more. As in the parable of the talents, to him who has, more (responsibility and trust) shall be given by the Rockefeller Foundation.

At about the age of 60, Rockefeller began to wind down his remarkable business career to focus more on philanthropy, his family, and leisure. He took up gardening, started riding more on his horses, and began playing golf. Yale University might ban the tango, but Rockefeller hired an instructor to teach him how to do it. Even in recreation, Rockefeller wanted to discipline his actions for the best result. In golf, he hired a caddy to say “Hold your head down,” before each of his swings. He even strapped his left foot down with croquet wickets to keep it steady during his drives.

In a way, Rockefeller’s life was a paradox. He was fascinated with human nature and enjoyed studying people. Yet his unparalleled success in business made friendships awkward and forced him to shut out much of the world. To his children, Rockefeller was the man who played blind man’s buff with great gusto, balanced dinner plates on his nose, and taught them how to swim and to ride bicycles. But from the world he had to keep his distance: he was a target for fortune hunters, fawners, chiselers, and mountebank preachers. Hundreds of hard-luck letters were written to him each week.

Retirement, however, liberated him more to enjoy people and nature. On his estate in New York, he studied plants and flowers. Sometimes he would drive out into the countryside just to admire a wheat field. Down in Florida, he liked to watch all the people who passed his house and guess at what they did in life. He handed out dimes to neighborhood children and urged them to work and to save.

Naturally, Rockefeller had some disappointments in his last years. He was sad that Standard Oil had been broken up by the Sherman Act and that the Russians had increased their foreign oil sales. He also was saddened by the Great Depression of the 1930s. Still, Rockefeller knew he had lived a full life and had been a key part of the two big transformations in the oil industry: the making of kerosene for lighting homes and the making of gasoline for running cars. Rockefeller loved life and wanted to live to be one hundred, but he died in his sleep during his ninety-eighth year in 1937.