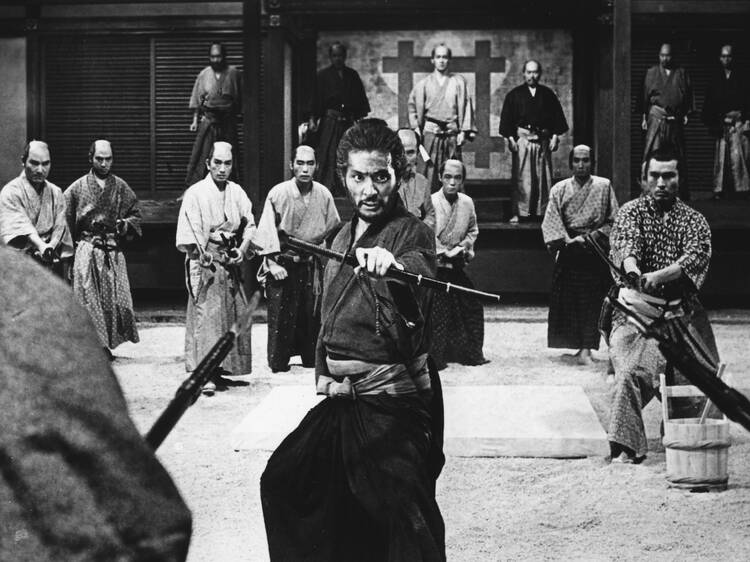

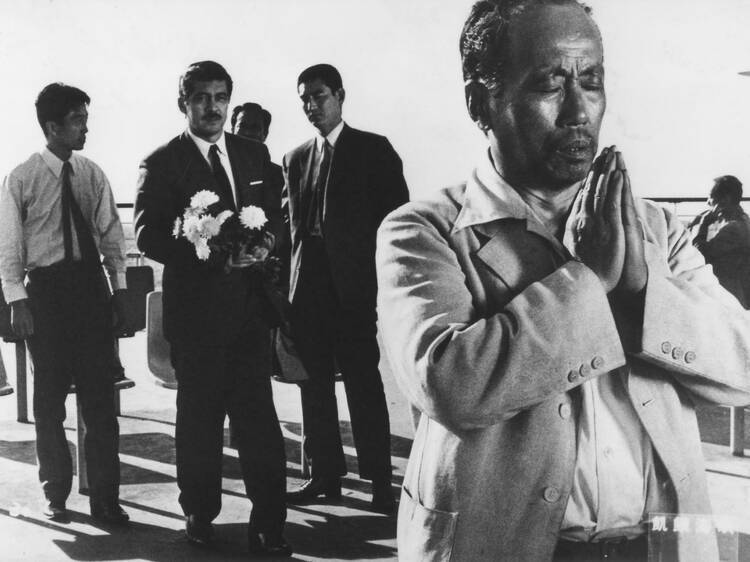

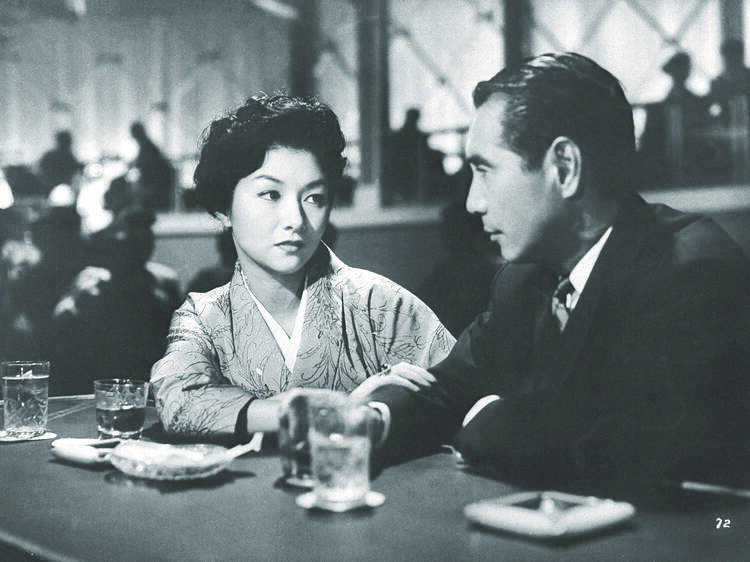

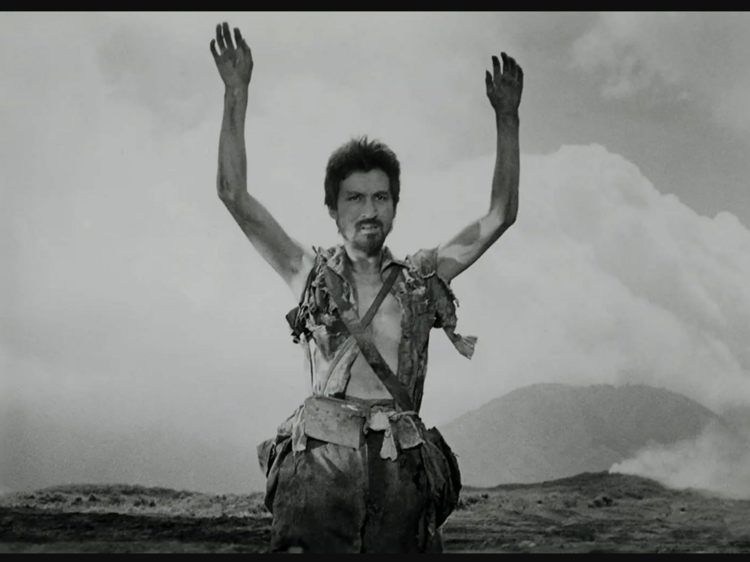

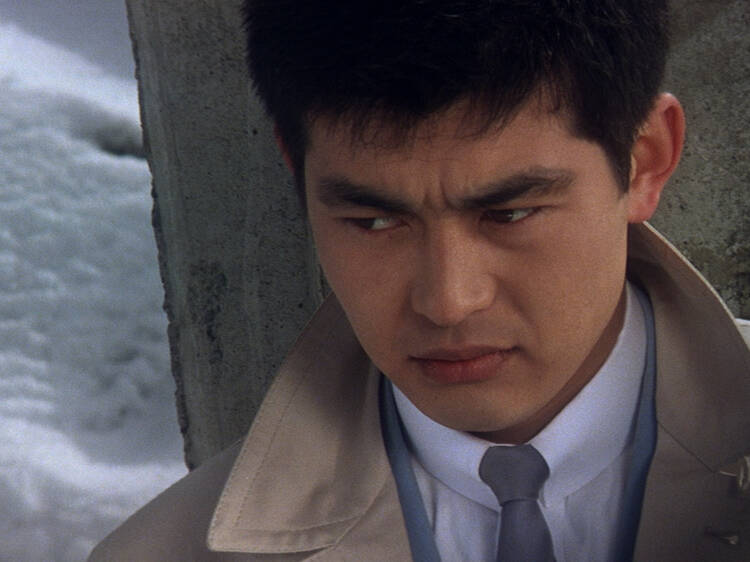

Director: Akira Kurosawa

If you’re looking for an entry point to Japanese cinema, or world cinema – or, shoot, just cinema in general – consider this your diving board. For experts, it probably seems a bit remedial at this point, but the most masterful of Akira Kurosawa’s many masterpieces has served as a gateway for generations of filmgoers precisely because of its simplicity. An impoverished Japanese village is besieged by bandits, so the townspeople pool their resources to hire a ragtag group of samurai to protect them. From that basic foundation, Kurosawa spins an epic that is, at turns, exhilarating, funny and emotionally resonant, not to mention highly influential – Hollywood has lifted the plot for everything from The Magnificent Seven to A Bug’s Life. Its 207 minute runtime might seem daunting, but trust us: you’ve never felt two and a half hours whizz by so quickly.—Matt Singer