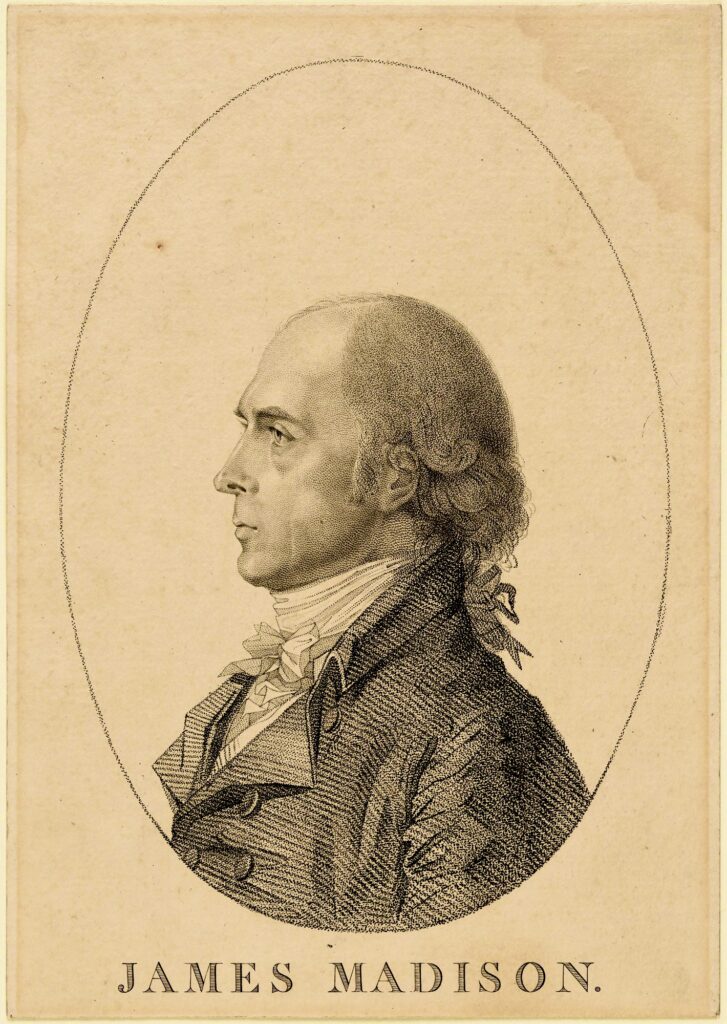

James Madison Proposes a Bill of Rights

On June 8, 1789, Virginia Congressman James Madison rose from his seat in New York City’s Federal Hall and urged his colleagues to consider “some things to be incorporated into the Constitution” that he felt “bound by every motive of prudence” to introduce. The first Congress under the new Constitution had many problems to address: it needed to establish new departments for the executive branch, rules for each house, a post office, and a judicial system; and it needed to reaffirm the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Now Madison placed on its agenda a set of resolutions that became the Bill of Rights.

Congressman Madison reminded his colleagues that although the new government was “acceptable” to most Americans, it was not “acceptable to the whole people of the United States.” Madison argued that “the great mass of the people who opposed it, did so because it did not contain effectual provision against the encroachments on particular rights.” In other words, the new Constitution lacked a Bill of Rights. Therefore, Madison argued, prudence required inserting “safeguards” into the Constitution restricting the federal government from infringing on the people’s civil liberties.

The Political Complexities Madison Faced

I imagine that most American history and government teachers would read this opening paragraph and nod in agreement. “Yeah, that’s pretty much the way I teach it,” they may think. I plead guilty to teaching the origins of the Bill of Rights this way. My students learned that separate conventions debating the ratification of the Constitution took place in each state. The proponents labeled themselves the Federalists. Their antifederalist opponents expressed a variety of objections, but agreed that the lack of a declaration of rights was a glaring defect of the new system. I introduced this big idea, offered some evidence supporting the usual account, and moved on to the next topic in the standards I needed to cover. Yet this simplification overlooks the complexity Madison faced when proffering his resolutions to the first House of Representatives.

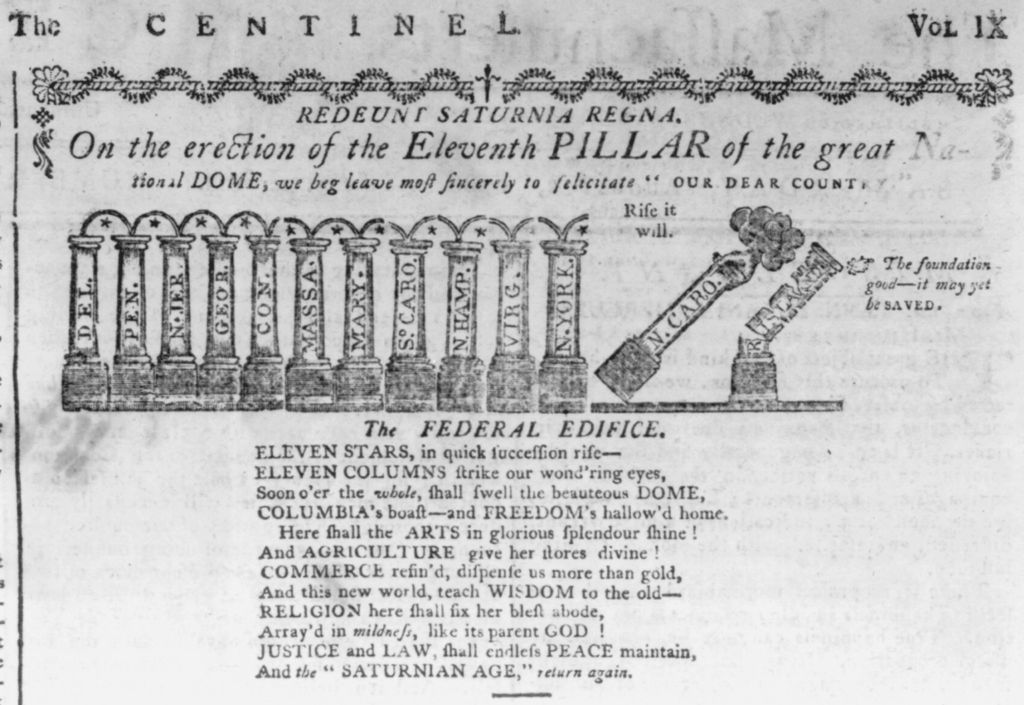

Two states, Rhode Island and North Carolina, had yet to ratify the Constitution. Madison hoped that incorporating specific protections for individual rights “would satisfy the public mind that their liberties will be perpetual,” enticing the two holdouts to strengthen the union by joining their sister states in ratifying the Constitution. Additionally, two states—New York and Virginia—had formally gone on record requesting a second Constitutional Convention designed to address defects they saw in the new federal system. The possibility of a second convention alarmed Madison. He was “unwilling to see a door opened for a reconsideration of the whole structure of government.” He doubted that “if such a door were opened, we should ever be very likely to stop at that point which would be safe to the government itself.” But he also told his colleagues that he wished “to see a door opened” to “provisions for the security of rights” and expressed confidence that most of the country welcomed such provisions.

Madison was not alone in his belief that the country would welcome an expressed protection of rights in the Constitution and that opponents of the new government would change their minds about the system “if they were satisfied on this one point.” In his First Inaugural Address, President George Washington suggested Congress delay consideration of most amendments that addressed complaints from opponents. However, he welcomed those that demonstrated “a reverence for the characteristic rights of freemen, and a regard for public harmony.” In a letter dated December 20, 1787, Madison’s friend and fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson added his voice to concerns about the framework of government that emerged from the Philadelphia Convention earlier that year. “First” among Jefferson’s objections was “the omission of a bill of rights providing clearly and without the aid of sophisms for freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies . . . and trials by jury in all matter of fact triable by the laws of the land.”

Madison’s Proposals Vs. Congress’s Decision

There are interesting differences between Madison’s proposed changes and the Bill of Rights ratified in 1791. Most of these differences might be considered trivial. Madison suggested that the changes be inserted into the body of the Constitution. Instead, the House of Representatives proposed 17 amendments to the Constitution, which the Senate consolidated into 12 amendments. The states ratified ten of the twelve amendments. One of the two amendments not approved affected representation in the House. The second was ratified in 1992 as the 27th amendment. It prohibits Congress from raising the pay of a sitting Congress.

One particular proposal Madison made and that Congress rejected could not be called trivial. He called for limits on both the federal and state governments. He urged that states be prohibited from infringing on “the equal right of conscience, freedom of the press, or trial by jury in criminal cases.” Madison acknowledged that several states had these rights protected in their state constitutions, but he called for uniformity, because “state governments are as liable to attack these invaluable privileges as the general government.”

In commenting on the danger from state governments, Madison returned to a theme he first raised when critiquing the Articles of Confederation before the Constitutional Convention of 1787. He fully developed this argument in his famous essay defending the Constitution, Federalist 10. Madison foresaw that the greatest danger to liberty in a republic was the potential for a tyranny of the majority. The majority can outvote minority factions. Minority factions cannot outvote the majority, and the majority rules in a republic unless or until majority opinion shifts. Majority factions gather credibility from the simple fact they are a majority and might claim that the principle of “majority rules” grants them autocratic authority. In an effort to counter majority faction in the states, the Virginia plan presented to the Constitutional Convention of 1787—believed to be authored by Madison—called for the national legislature to “negative all laws passed by the several states” that conflicted with the Constitution.

Madison’s proposal to limit both state and federal governments by a Bill of Rights is interesting, given the Supreme Court’s changing interpretation of how far the original ten amendments applied. In Barron v Baltimore, 1833, the court ruled that the Bill of Rights limited the federal government, not state governments. It was not until 1925, in the case of Gitlow v New York that the Supreme Court said the First Amendment’s protection of free speech applied to state governments. The Court cited the due process clause of the 14th amendment as the basis for applying the Bill of Rights to the states, a process known as incorporation.

It is fascinating to consider how constitutional limits on the state governments’ abilities to restrict the freedom of speech and of the press may have impacted antebellum reform efforts like abolitionism. The slaveholding South blocked abolitionist mail from being delivered to southern households. Would a constitutional guarantee of a free press have prevented such action? Would the freedom to publish abolitionist literature in the South have encouraged anti-slavery voices in the region? Although these questions are unanswerable, students may learn from discussing them. What choices were best, the ones made by the generation of the early republic, or those they rejected?