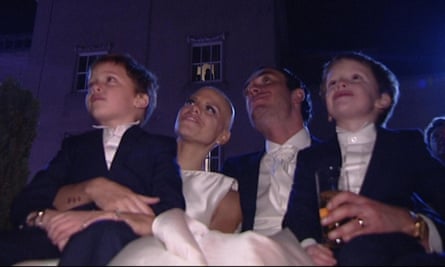

‘She was never a fairytale person. She never believed in pretty things,” says Jackiey Budden gruffly at the beginning of Jade: The Reality Star Who Changed Britain, Channel 4’s three-part series about Budden’s daughter. We see Jade Goody herself, bald from her cancer treatment, flying in a helicopter to marry her boyfriend Jack Tweed. It ought to be a fairytale wedding but there’s something clearly wrong. Goody is in pain and is about to die.

Other pictures from the time show her wrapped in a blanket and sucking painkilling lollipops. But here, her eyes are wide in wonder as she looks down. Perhaps it’s the drugs, perhaps it’s the knowledge of what is coming, perhaps she is taking in her life. It is haunting. So maybe she was right never to believe in pretty things, right to grab everything fame gave her. Perhaps Goody knew happy endings were not for the likes of her.

Her story intrigues because it is a tale of a more innocent time, when the culture was about to turn. It is pre-social media and smartphones, when reality TV was beginning to make stars of people who had no discernible talent beyond “being themselves”. Goody, aged 20, rocks up as a ball of energy, declaring: “I don’t think before I talk.” This is 2002, the third series of Big Brother.

Born in Bermondsey, south London, to a drug-addict mother and a father who was a pimp, Goody had it very hard. On TV, though, she was relentlessly cheery and cheerily ignorant. Many basic facts escaped her. She did not know where East Anglia was. A national debate ensued about a failing education system. She got drunk. She was vulnerable. She was silly, and at one point naked.

The public were encouraged to despise her by a fit of fake respectability from the tabloids whose symbiotic relationship to reality TV was in full swing. This chatty girl was soon an object of scorn: a female chav. Chavs were bad enough but female ones were even worse. It was fine to call her a pig. It was fine to mock her mixed-race features, it was fine for Graham Norton to dress up in a fat suit to imitate her, or for Jonathan Ross to say men would be wanting to “shag her brains in”.

To make matters worse, she broke Channel 4’s “penetration protocols”. (Me neither.) Tim Gardam, former director of TV at the channel, is on hand to explain the horror of middle-class TV executives at seeing Goody giving a blowjob under the covers. She was everything that is feared about working-class women: shameless, promiscuous and gobby. This, remember, was in the days before internet shaming. She became public enemy No 1 until a strange thing happened and the public, instead of lapping up the tabloids’ bullying, started to understand her a little more and condemn her a little less.

Kevin O’Sullivan, the Mirror’s anti-Big Brother correspondent, who boasts of writing the vilest stuff, then performed “a reverse ferret” as instructed by his editor Piers Morgan – and instead wrote of how she had triumphed over adversity. She didn’t have a childhood. Big Brother was as near as she would come to one. She didn’t win but she was the one who made money and controlled her own image, setting up pap shots. This “stupid” girl soon had a sports car and wondered why she couldn’t be mayor. Tony Blair had told us we lived in a meritocracy, after all.

She was, I think, part of the holy triumvirate of female chavs: Goody, Kerry Katona and Jordan, who preoccupied the tabloids. She was living the dream in Essex. Her mother appeared on Extreme Makeover, getting breast implants on TV. Instinctively, Goody knew how to be a content provider. Her mistake was agreeing to go into the Celebrity Big Brother house in 2007, along with her mother and her boyfriend.

Seeing this now, as we do in the documentary’s upcoming episode two, is utterly bizarre. There is the late, great Ken Russell calling her “slightly demented” as he shuffles out of the house in his slippers. There is Leo Sayer going berserk and escaping. There is Jermaine Jackson sitting there bemused. The producers decided to bring a master/servant dynamic into an already conflicted house. Budden, Goody’s mother, was soon evicted. Goody was distraught and ganged up with former Miss England Danielle Lloyd and S Club 7 singer Jo O’Meara against Shilpa Shetty, who was Bollywood royalty and used to having actual servants.

What did the producers think would happen? Goody called the Indian film star “Shilpa Poppadom” and this racism was discussed on the news and in the House of Commons. When Gordon Brown, then chancellor of the exchequer, flew to India to discuss trade, he was met by more than 20 news crews asking him about a programme he had clearly never seen. In India, effigies of Goody were burned.

She was soon shunted out of the house with no public reception and made to confront what she had done. The bullied had become the bully and she was once more a figure of hate. This was popular entertainment as news. She sobbed endlessly: “I won’t defend myself.” What did it tell us about class, race and celebrity? And redemption? It told some of us very complicated things. Goody was mixed race and grew up in an area where the National Front was active and the flats were smeared with graffiti. Yet she was ignorantly racist to an Indian woman.

It told us that no one really escapes their class, even if they have a fragrance named after them. It told us that class was something that could be played by mainly middle-class TV producers. From Jeremy Kyle to endless shows about benefit cheats, we can see the groundwork being laid for the othering of people at the bottom of society. Austerity depended on seeing these people as totally undeserving.

To try to make amends, Goody entered the Big Brother house in India. After two days, she was brought back because she had been diagnosed with cervical cancer. Heartbreakingly, she said: “There’s a cancer cell and there is me. I will always be stronger than the cancer cell – cos I need to live.” She needed to live for her two sons. Her relationship with their father had broken down partly due to phone-hacking, another feature of those times.

It is brave of Channel 4 to broadcast this now, for it is impossible not to see its own producers as culpable – not just for her rise but for her fall. Goody’s legacy, for a while, was more young women getting screened for cancer, but rates have since fallen again. In 2014, her mother was told her benefits would be cut: “They said I ain’t dead, I ain’t blind, I can walk and I use my right hand so I’m not disabled no more.”

Class will win out. Goody had gulped up every minute of her time. We sat there watching her fall as though we were outside it, rather than part of it. We bemoaned the fact that kids want to be famous for the sake of being famous, yet we know social mobility is in decline. We crave celebrity and we then want to punish those who achieve it.

Goody embodied a shame-and-blame culture around class, race and female desire. She was destroyed by that, as well as cancer.

Her funeral was televised. Of course it was. That final public act, though: the white wedding dress, no veil to cover her head, no hiding what was happening to her. It was an image that defied every fairytale going. It was as real as it gets.

I don’t know if she knew what she was doing. I like to think she did.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion