On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson trotted out to first base for the Dodgers at Brooklyn's Ebbets Field, erasing the unofficial color line that had stood in big league baseball for nearly 60 years. By the end of the season, his dazzling play had earned him baseball's inaugural Rookie of the Year Award, cementing the belief that Black people more than deserved a place alongside the best white players in the national pastime.

For many, the story of Robinson ends there. Or maybe when he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962. What often goes untold is his continued battle for equality after leaving baseball, a period that lasted nearly twice as long as his major league career.

After announcing his retirement from the sport in early 1957, Robinson was named vice president for personnel at the Chock Full O' Nuts coffee company. He also joined the NAACP as chair of its million-dollar Freedom Fund Drive, eventually earning election to the organization's board of directors.

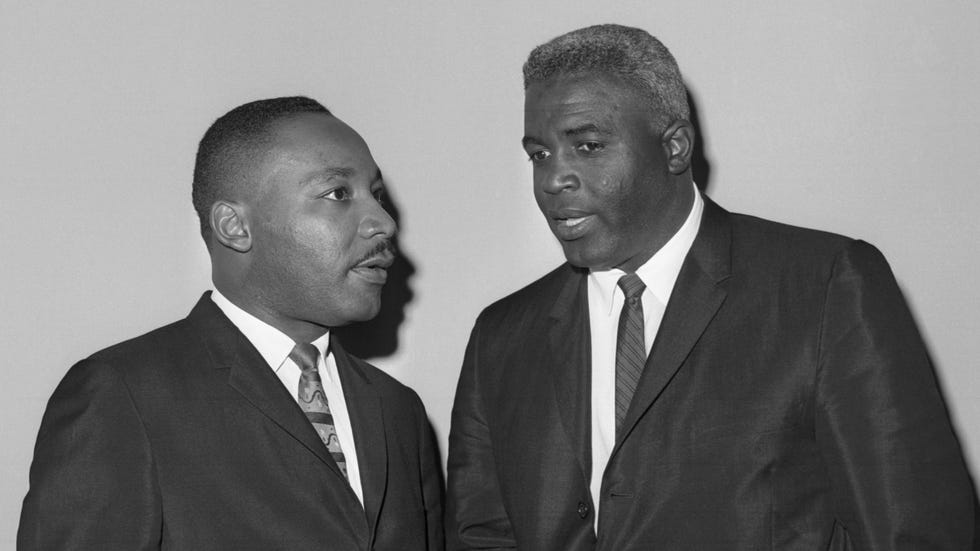

However, executive positions weren't enough for the former athlete, whose competitive juices had him itching to get back into the public arena. He joined Martin Luther King Jr. as honorary chairmen of the Youth March for Integrated Schools in 1958 and became involved with Dr. King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He also began writing a syndicated newspaper column, through which he mused on matters of race relations, family life and politics.

Robinson took to advocating advancement through "the ballot and the buck." He became a prominent political supporter, throwing his weight behind Richard Nixon during the 1960 presidential election, and eventually emerging as a strong ally of moderate New York Republican Nelson Rockefeller. He also backed his talk for economic independence by helping to found the Black-owned Freedom National Bank, which provided loans and services for the minority community.

However, by the mid-1960s Robinson was becoming an outdated figure in the Civil Rights movement. An advocate of the non-violent approach of Dr. King and the NAACP, he rejected the more extreme measures proposed by charismatic young leaders like H. Rap Brown and Huey Newton, and engaged in a nasty back-and-forth with Malcolm X through his column. Even his shine as a Black sports icon was somewhat diminished, with contemporary athletes like Muhammad Ali and Jim Brown dominating their fields and speaking out in ways that had seemed unthinkable 20 years earlier.

Robinson had his own share of issues with the NAACP, and in 1967 he publicly split with the organization over its "unresponsive" leadership. Furthermore, his political views left him increasingly isolated as an activist; he clashed with Dr. King over the support of the Vietnam War, and he returned to Nixon in 1968 and 1972, even as many of his fellow African Americans were abandoning the Republican Party.

Still, Robinson continued fighting for larger causes even as his own health deteriorated. In 1970 he launched the Jackie Robinson Construction Company to build low and moderate-income housing for minorities. In October 1972, during a ceremony to throw out the first pitch before a World Series game, he made a point to remind everyone that baseball had yet to appoint its first Black manager. Nine days later, he was dead from a heart attack.

Robinson is justly remembered for breaking down racial barriers and opening the doors of opportunity for Black people across professional sports. But long after he was done with baseball, he continued to fight for equal footing as a writer, organizer, speaker, businessman and political supporter, facing a far more expansive playing field without many of the natural advantages he enjoyed as a gifted athlete. For that, he deserves just as much credit when we remember him as an American hero.