Thousands of people in Alabama crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge from Selma into Montgomery on Sunday to recreate a pivotal moment in the civil rights movement on its 52nd anniversary.

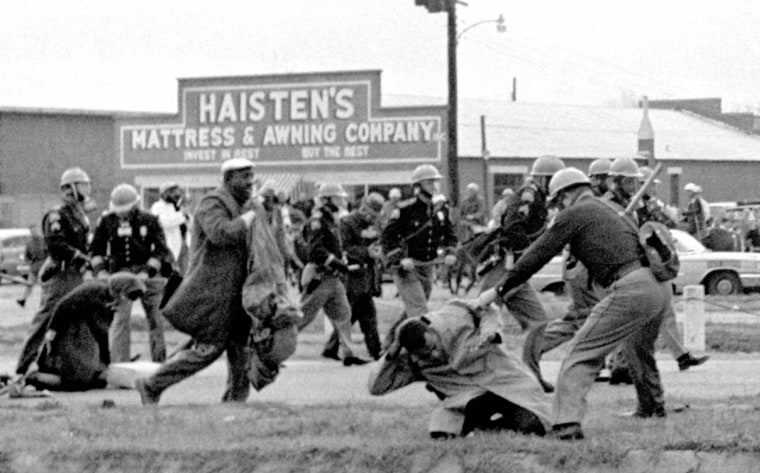

On March 7, 1965, images of police beating and throwing tear gas at 600 marchers flashed across television screens nationwide, capturing what is now known as "Bloody Sunday."

One hundred years earlier, the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution granted equal rights to all citizens, yet Jim Crow laws maintained segregation and disenfranchised black Americans.

In honor of the march's 52nd anniversary, here are five lesser-known facts about Selma.

Push for Voting Rights Sparked Selma Protests

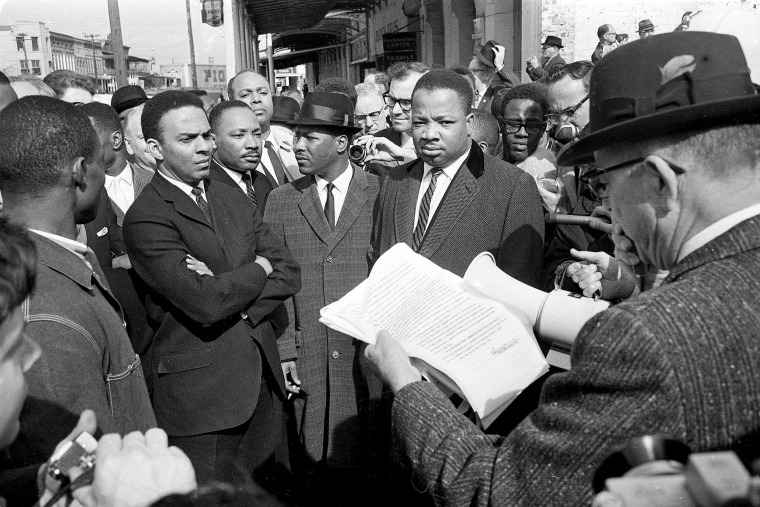

Before the march, civil rights groups had been pushing for equal voting rights in the city since 1963. A 1961 Civil Rights Commission report revealed that less than 1 percent of the voting-age black population was registered in Montgomery County.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) began holding "Freedom Days" in the city focused on canvassing door-to-door to persuade black Americans to register to vote.

The Ku Klux Klan and local police often fought against efforts to register black voters in Selma and other states. According to The New York Times, Selma Sheriff Jim Clark once sent a photographer to take pictures of activists who participated in a 1963 "Freedom Day" and warned he would share the photos with their bosses.

In a letter written to The New York Times in February 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote: "This is Selma, Alabama. There are more negroes in jail with me than there are on the voting rolls.”

A little over a month later, the march from Selma to Montgomery took place.

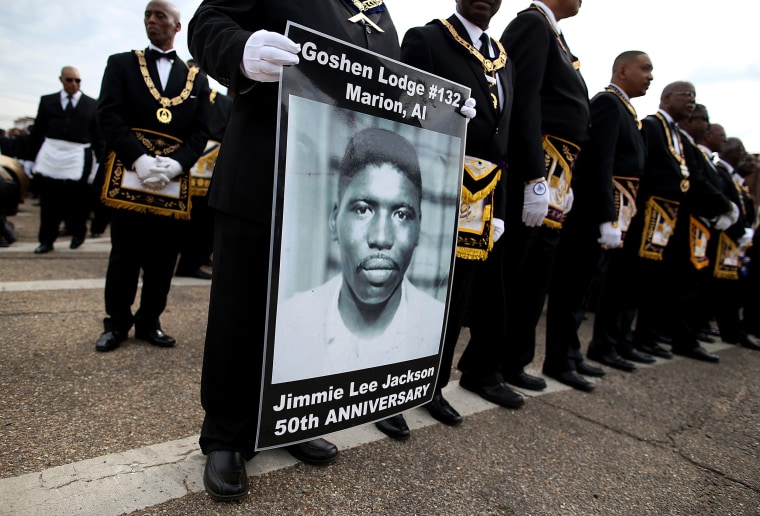

Jimmie Lee Jackson: The Inspiration for the March

One of the first images that comes to mind when Selma is mentioned is likely Dr. Martin Luther King marching hand in hand with dozens of civil rights advocates throughout the streets. Less well-known is Jimmie Lee Jackson — the man whose death set the demonstrations in motion.

Jackson was a 26-year-old African-American who was fatally shot on February 18, 1965, by an Alabama state trooper while he was in Marion protesting the arrest of Southern Christian Leadership Conference field secretary James Orange. Jackson was reportedly attempting to stop his grandfather and mother from being beaten when the trooper shot him in the stomach. Jackson died eight days later.

Civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Jackson's funeral. In the summer of 1965, King gave a speech in Syracuse where he mentioned Jackson's death.

"Before the victory's won, some like a Medgar Evers, like a Mrs. Viola Liuzzo, like a Rev. James Reeb, like a Jimmie Lee Jackson, may have to face physical death .... (if) the physical death is a price that some must pay to free their children and their white brothers from an eternal death of the spirit, then nothing can be more redemptive," King said during a speech in Syracuse, according to a transcript.

The state trooper who shot Jackson, then 77-year-old James Bonard Fowler, was charged with murder in 2007, 42 years later, The Associated Press reported. Fowler pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of manslaughter in the case and was freed early from a six-month jail sentence.

The Bridge Marchers Crossed Was Named After a KKK Grand Dragon

Built in 1940, the Edmund Pettus bridge connected Selma to Montgomery. As protesters marched from one county to the other, they crossed a bridge named after Civil War Confederate general Edmund Pettus, who later became Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama.

Pettus, whose family once owned slaves, was regarded as a hero in Alabama during and after Reconstruction, according to the Smithsonian.

In 2015, there was a movement to rename the bridge, which would have required approval from the State of Alabama. A petition gathered 189,000 signatures and an Alabama Senate bill aimed at renaming the bridge to the Journey to Freedom bridge passed. The bill later died in the House, according to AL.com.

In a letter written in 2015, Reps. John Lewis and Teri Sewell defended keeping the name of the bridge, arguing that erasing the name would not erase America's history of racism.

"Renaming the Bridge will never erase its history. Instead of hiding our history behind a new name we must embrace it — the good and the bad," the letter reads.

Women Played an Important Role in Organizing the March

From Amelia Boynton Robinson to Marie Foster, black women played a key part in organizing the Selma march and were among the hundreds who were beaten by police.

Born in 1911 in Savannah, Georgia, Boynton Robinson was instrumental in persuading King to focus on civil rights efforts in Selma. She opened her Selma home to the SCLC as a place to discuss and plan the march that became known as "Bloody Sunday."

While walking on March 7, she was knocked unconscious by a state trooper. A photo of Boynton Robinson laying on the ground with a white officer above her was plastered across newspapers the next morning, according to The New York Times.

Foster, born in 1917, was also beaten by troopers during the "Bloody Sunday" march.

In a United Press International interview quoted in the Los Angeles Times, Foster said, ''It was a trooper who hit me. I lay on the pavement with my eyes closed. I didn't move. I stood my ground.''

Both women spent years pushing to register black Americans to vote — Foster founded the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute in Selma and Boyton Robinson was one of the first African-American women registered to vote in Selma.

The March Was a Catalyst for the Voting Rights Act, and Inspired Movements Elsewhere

Five months after the march to Montgomery, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The act protected African-Americans' right to vote, ostensibly granted in 1870 by the 15th Amendment.

The march in Selma also inspired other grassroots movements. Located near Montgomery and Selma, activists in rural Lowndes County formed an all-black political party called the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) one year after the march.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries, a professor of history at Ohio State University, published a book in 2010 detailing events in Lowndes County, Alabama, following the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He writes that in 1966, most African Americans in Lowndes County were still too fearful of intimidation at the ballot box.

"Their fear stemmed from the county’s long, bloody history of whites retaliating against blacks who strove to exert the freedom granted to them after the Civil War," the novel's description reads. "Amid this environment of intimidation and disempowerment, African-Americans in Lowndes County viewed the LCFO as the best vehicle for concrete change."